DONATELLO: The world of a genius

DONATELLO: The world of a genius

Italy is an inexhaustible source of all kinds of unexpected experiences – culinary, as well as cultural. I open the door to something that has fleetingly interested me and impressions, memories, dreams and a host of other phenomena rush over me. Like when a month ago, together with my American friend Joe, I visited Florence and was confronted with Donatello’s art. An exhibition about his life, works and influence was presented in the palaces of Strozzi and Bargello.

I had previously visited Florence many times and in churches and museums been confronted with Donatello’s work, read about the Master and heard my art professor tell about him, but I had never seriously realized the extent of Donatello’s genius. The great and revolutionizing influence he had had on his followers. I once again realised the astonishing moment in human history during which he and his good friend Brunelleschi constituted the eye of the hurricane. Donatello with his sculptures and reliefs, Brunelleschi with his theories about the central perspective and the dome he created above Santa Maria del Fiore.

The two friends had visited Rome together, where Donatello had been overwhelmed by the presence of cultural treasures left behind by past times; the imaginative richness, balance and perfect harmony of the Greek and Roman statues and sarcophagus reliefs, this while Brunelleschi (1377-1446) in detail studied ancient arch techniques and immersed himself in the writings of Vitruvius (80-15 BC).

Brunelleschi was the more theoretically/mathematically versed of the two geniuses, while Donatello was a consummate artist/craftsman, with an intuitive sense of the expressions his art would take to satisfy his clients’ expectations, and more than that – astonish them. Donatello’s contemporaries often pointed to his lack of education, claiming that he was barely literate. I doubt if this is really true, assuming it was a myth intended to suggest that his genius was God-given, just as Muslims often state that Muhammad could neither read nor write, thereby implying that his teachings were forthwith dictated by God.

Donatello, actual name was Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi. Donatello is a diminutive, an epithet given him due to his small stature. He was born in Florence 1386, as the son of Betto Bardi, whose occupation was listed as “wool carder”, although he also occupied himself as goldsmith. Wool carder could mean that Bardi was a proletarian, though it could also mean that he was owner of a wool carder manufactory, something that seems to be indicated by the fact that he was a Guild Master. The guild he belonged to would then have been the powerful Arte della Lana, a craft association that included wool manufacturers and wealthy merchants involved in Florence’s flourishing wool industry.

During Donatello's lifetime, the wool business employed no less than 30,000 workers, a third of the population of Florence, who annually produced 100,000 metres of textiles and clothing.

The buyers and exporters of wool and cloth was over time able to amass large fortunes, which they used to lend at interest to various European rulers. Most of these bankers were organized within a guild called Arte di Calimala. The strange name Calimala, Calm Her, came from the name of the street where Arte di Calimala’s headquarter was located. Through their wealth, members of this guild were able to influence and manipulate the rulers of Florence. Most influential among the members of this particular guild was the Medici family.

A picture in an Italian comic book illustrates the state of affairs in Donatello’s Florence. Donald Duck is toiling away shearing sheep and collecting wool while his Uncle Scrooge is counting the money he has received through wool sales and banking.

Like several other northern Italian trading cities, Florence was during Donatello’s lifetime governed by an assembly called the Signoria. Its nine members were chosen from the city’s leading guilds. Six of them came from guilds called Priori, i.e. the six ancient and most powerful guilds, among them the Arte della Lana and Arte di Calimala. Two additional members were elected from the fourteen ”minor” guilds. The ninth member of the Signoria was named Gonfaloniere di Giustizia and served as its chairman. He was elected every two months, not by lot but by members of the outgoing Signoria.

One of the several peculiarities of this form of government was how the members of the Signoria were elected and the short time they served as decision makers. The names of all guild members over the age of thirty were placed in eight leather bags. Every two months these sacks were carried out of the church of Santa Croce, where they were kept and during a short ceremony the names were drawn at random. Only men who were not in debt could be elected, moreover they would not have had a seat in the Signoria during the past year and they could not have any family ties to the men who had served during the previous term. Immediately after their election, the nine members of the Signoria were expected to take up residence in the Palazzo della Signoria, which facade was adorned with the coats of arms of the guilds. There they would stay for the two months that their mission lasted.

That's how it all worked in principle, but over time intrigues and manipulations confused the already complicated system and power effectively came to rest with the Gonfaloniere di Giustizia, an office that came to be dominated by the increasingly powerful Medici family. However, this did not mean that the guild system and its influence on Florence’s power game disappeared. For several centuries, the Signoria continued to dominate the economic and political life of the city.

The Arte della Lana, of which Donatello’s father was a member, controlled the entire process from the raw, packaged wool that on a daily basis arrived in the city, to the finished textiles produced at looms scattered among private homes and manufactures located within the city walls.

Like other guilds, the Arte della Lana coordinated and controlled the activities of its members; guaranteed the quality of the production, set prices, regulated wages, checked the training of journeymen, tested and decided who should be awarded a master craftsman's certificate.

Each guild had its patron saint, while its board resided in a palace, generally they also supported and paid for Catholic masses and the maintenance of a specific church. The mighty Arte della Lana resided in an impressive palace in the very centre of the city, its patron saint was St. Stephen and its church was none other than Florence’s Duomo – Santa Maria del Fiori.

In niches around the Chiesa di Orsanmichel, there are statues of the patron saints of the various guilds. Arte della Lana’s St. Stephen had been sculpted by Lorenzo Ghiberti, in whose renowned bottega Donatello at the age of seventeen had been accepted as an apprentice.

During Donatello’s lifetime the bottega system was well developed in Florence and the city counted on anumber of master bottegas. A bottega was more than an artist's studio, more than a place of learning for future masters and could best be described as a workshop that, under great competition, delivered commissioned work to various patrons. Much of the work was governed by strict routines marked by extremely important craftsmanship and tasks which depended on clients’ requirements, lack of time when it came to the execution of the complicated works, as well as the guild system’s production control and detailed regulations.

In particular, the maufacture of paints was an essential part of a bottega’s activities and for that reason Florentine painters belonged to one of the six most powerful guilds that made up the Priori – Arte dei Medici e Speziale, the Crafts Association of Doctors and Apothecaries, i.e. an association of specialists who made and used drugs and various decoctions. In addition to artists, the Arte dei Medici e Speziale also included shopkeepers who sold spices and textile dyes.

Each bottega produced its own colours. Paint production, as well as the careful preparation of canvases and specially treated wooden boards which constituted the base/groundwork for paintings, were labour-intensive processes handled by the bottega’s apprentices.

Colour pigments came from a variety of sources. They could consist of different types of soil containing minerals and clay, such as Raw or Burnt Sienna and Burnt Umbra. The pigments were often based on toxic substances such as mercury, lead, sulfide, tin, and cinnabar. They could also be constituted by very expensive imports such as Indian Yellow, which was made from the urine of cows fed on mango leaves, or most expensive of them all – the blue stone, lapiz lazuli, which was brought to Florence from Badakshan by the upper reaches of the river Amu Darya. To obtain the best pigments, artists were often forced to experiment on their own, or to gain such high esteem that patrons were willing to pay for their access to coveted and expensive pigments.

The pigments had to be grinded down to small, fine grains by using a runner, a cone-shaped stone with a flat bottom surface that was used to crush the pigments against a smoothened stone slab. When the pigments obtained the right grain size, they were compacted into a paste, by adding different binders. During Donatello’s time, the most common binder was egg yolk mixed with water – tempera. An alternative was to add oil, usually from linseed, to the solution, thus making it dry faster and permitting application to softer surfaces like canvas, instead of the commonly used base made of pine or poplar. Other common binders were beeswax and casein.

The artists’ workshops also produced various forms of varnish. The medieval name for varnish was the Latin word veronix, which gave rise to today's vernissage, the opening day of an art exhibition. During the Renaissance, this meant that when the varnish had dried the work of art could be considered completed and thus presented to the client. If the client rejected the result, it could mean a great loss of prestige for the bottega, as well as a serious financial setback.

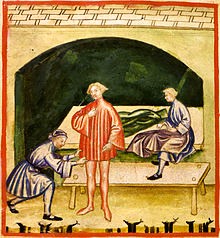

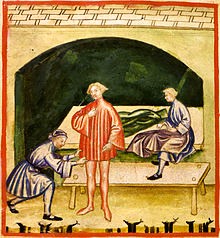

Within a bottega, the hard-working apprentices were called garzoni, boys. Donatello’s entry as a garzone in the bottega of Master Lorenzo Ghiberti took place at an unusually old age. Generally, most garzoni accepted into a bottega were around ten years old. They were entrusted to their Master’s care. He nurtured, disciplined and taught them and they were considered to be part of his household. They lodged and ate together with their master’s family. Several garzoni did not advance from working with colours and panels, but the most skilled and enthusiastic of them were by the master taught to sketch, read and wtite, and could finally be allowed to participate in the completion of his works of art. Gradually, the most skilled garzoni were entrusted with more important tasks than the painting of decorative details and completion of the master's contours, or the colouring of previously delimited surfaces.

The guild required a master to provide his garzoni with an accartati, contract, and a fixed salary, the latter was usually quite modest—generally five or eight gold florins in a year, compared to a skilled labourer’s wages of about thirty-five florins within a year. At the end of his apprenticeship, a garzone could be offered to undergo a journeyman’s test. If he succeeded he was declared a journeyman and thus the opportunity to offer his services as an independent artist, though a journeyman was not allowed to establish his own bottega. That required membership in the Arte dei Medici e Speziale.

Guild members provided membership if a journeyman could present a Masterpiece (from which our contemporary word originates) that was accepted as such by selected guild members. If the jorneyman was accepted he was appointed Master of Arts and through a specific certificate he was thus granted the right to open a bottega of his own. First, however, a would-be Master had to prove he was the recognized son of a guild-member and willing to pay an entry fee, as well as signing a contract stipulating that he accepted the guild’s statutes and committed himself to submit an annual contribution to the guild’s common coffers.

The strict work discipline, fixed routines, the practical work that attached great importance to every single detail, the rigorous quality control of the guilds, fierce competition, the cooperation between a Master and his garzone, as well as the team spririt reigning within the guilds contributed to the fact that many Renaissance artists at an early age became exceptionally skilled craftsmen.

The earliest work of art that attributed to Donatello is a David he in 1409, at the age of twenty-three, carved in marble. The work had been paid for by Arte della Lana, the guild to which Donatello’s father belonged and it was intended to adorn one of the buttresses of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. However, it was not placed there because the guild members thought it was too small to be appreciated from ground level. The statue thus remained for several years in a bottega before the Signoria in 1416 brought it to its palace and placed it on a pedestal with the inscription: “To those who bravely fight for the defence of the motherland, the gods provide help, even against the most terrible enemies.” Apparently, the city counsellors thought that the young, bold David could serve as a role model for defenders of the Republic.

Criticism has been harsh while judging this first known work by Donatello. It has been written that the dimensions are wrong, that the whole work gives a ”formal and bland expression.” This David of his has been mercilessly compared to Donatello’s later skills and declared to be quite uninteresting.

Having now seen it in real life, I arrived at a different opinion. Considering the circumstances that predisposed the manufacture of the statue, it is certainly a masterpiece. David rests his left hand by his side while he, positioned in an elegant contraposto, triumphantly lifts his long robe to reveal Goliath’s severed head, which rests at his feet – still with both sling and stone embedded in the skull. Despite the distance from which the sculpture would be viewed, the grotesque head is fashioned in great detail and prominently presented, with its closed eyes and half-open mouth, through which the dead giant’s tongue can be glimpsed. The killing stone has penetrated the forehead, the congealed blood is difficult to distinguish from clumps of tangled hair.

There is no doubt that the arrangement was intended to adorn a buttress and thus be viewed from below. It all seems to be striving upwards. The gesture of the left hand opening the garment makes the head of the defeated Goliath seem closer to us than the rest of the of the statue. It looks like the gory head has been placed in a cave formed by the robe. At the same time, the opening in the mantel is reminiscent of a flame striving upwards, making the entire sculpture, with its Gothically curved movement, remind us of earlier madonna-sculptures carved from ivory and thus being adapted to the curvature of the elephant’s tusk. Through their elegantly curved movements, these Virgins and their child seems to be lifted up towards heavenly heights.

David’s oversized right fist, which has often been criticized, and his relatively small, and not so empathetically characterized, head, underline the impression that the sculpture was to be viewed from below and from a great distance. Considering all this, I got the impression, particularly since the sculpted details cannot be discerned from afar, that Donatello’s David was in fact his “Masterpiece”, his entrance exam to a guild. Since Donatello at the time was active in Ghiberti’s workshop, which master was better known as a sculptor than a painter, it is possible that the guild which he entered as a recognized master was the Arte dei Maestri di Pietra e Legname, the Guild of Master Stonecutters and Wood Carvers.

Donatello's good friend and peer Nanni di Banco, who together with Donatello had been given the task of decorating Il Duomo’s buttresses, did seven years later make a famous sculpture group, which impressed his contemporaries and became a great inspiration for Donatello (who probably assisted di Banco with the manufacture) – Quattro Santo Coronati, Four Crowned Saints. These four martyrs, whose names were unknown, are by tradition said to have been Christian sculptors who under the Roman Emperor Diocletian refused to make sculptures of “pagan” gods and therefore were placed alive within sealed lead coffins and thrown into the Sava River in present-day Serbia. They had since then been invoked as patron saints of sculptors and were of course the obvious choice of the Arte dei Maestri di Pietra e Legname to adorn its niche on the church di Orsanmichele.

In 1405 Nanni had been appointed master of the aforementioned guild. The four figures are masterfully arranged within a shallow semi-circular niche, where, through glances and discreet movements, they seem to be involved in a conversation. The solemn gestures, the toga-like clothing and the volume of the bodies testify that Nanni was influenced by ancient Roman sculptural art.

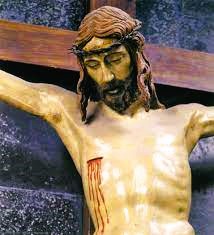

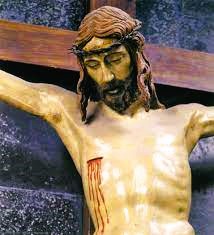

Donatello’s marble statue of David had, during the exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi, been placed in the same room as another youthful work by Donatello – the Crucifix in Santa Croce. It hung next to Brunelleschi's crucifix from Santa Maria Novella. The reason for this was surely an anecdote in Giorgio Vasari's (1511-1574) anecdote in his Le vite de’ più eccelenti pittori, scultori e architettori, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects.

For Santa Croce, Donatello had “with infinite patience” carved a wooden crucifix, which he proudly displayed to his friend Brunelleschi, who, however, after Donatello’s enthusiastic descriptions, had expected something better and thus could not help to smile. The disappointed Donatello sensed his friend’s displeasure and asked him, in view of their great friendship, to tell him what he really thought of the crucifix. After some hesitation, Brunelleschi once again looked intensely at the crucifix and stated: “You have put a peasant on the cross and not Jesus Christ, the most perfect man ever born.” Bitterly, because he had after all expected praise, Donatello replied: “If it was as easy to make something as it is to criticise, my Christ would really look to you like Christ. So you get some wood yourself and try to make one yourself.”

Without a word, Brunelleschi nodded and left the church. Not revealing it to anyone, he set about making a crucifix with the aim of surpassing Donatello’s creation. After several months’ of hard work he produced, with great perfection, a work which, according to him, was superior to Donatello’s crucifix.

One morning Brunelleschi invited his friend Donatello to dine with him. Donatello naturally accepted the invitation and they walked together towards Filippo’s house. As they passed the market, Brunelleschi bought some ingredients for the dinner, and after stating he had a couple of more errands to run he gave the market goods to Donatello and asked him to take them to his bottega. When Donatello entered the workshop, he found Filippo’s crucifix stategically placed in perfect lighting. Overwhelmed with surprise and admiration, Donatello dropped the apron in which he had placed the eggs, the cheese and other items brought from the market. At the sam moment, Filippo arrive and found his friend standing among the broken eggs, lost in thoughts and apparently stunned by suprise. Laughingly, Brunelleschi asked: “What’s your design, Donatello? What are we going to eat now that you’ve broken everything?” “Myself,” Donatello answered, “I’ve had my share for this mornig. If you want yours, you take it. But no more, please. Your job is making Christs and mine making peasants.”

It is a quite subtle anecdote and Vasari’s anecdote has for posterity come to characterize differences between Brunelleschi’s and Donatello’s art. It has time after time been commented upon by various art critis.

The difference between the two representations of the dying Christ is actually not that great. It is clear that the two wood carvers found their inspiration in Giotto’s Triumphal Crucifix in Santa Maria Novella. Painted in 1288, it was more than a hundred years old when Donatello and Brunelleschi made their crucifixes.

Giotto was inspired by Franciscan spirituality, which more than paying hommage to his glory and sublimity, or inhuman suffering, had emphasized Jesus’ humanity, love and poverty. Giotto’s crucifix thus depicted a dying man, with a realistically rendered body. There are no signs of barbaric beatings or physical suffering. Christ wears no crown of thorns and the only wounds he exhibits are from the spear thrust into his side and the nails hammered through his hands and feet. Maybe he is already dead.

It is in the expressions of their faces that the biggest differences between Donatello’s and Brunelleschi’s versions of the crucified Jesus become most apparent. It may be an illusion, though I assume that Donatello’s Jesus is closer to us than Brunelleschi’s Christ, with his tired, but still gentle gaze under almost closed eyelids, a half-open mouth with a swollen upper lip. His more prominent cheekbones and high forehead. The face, despite its lack of external damage, seems to bear witness to how an ordinary person exposed to contempt, betrayal and grotesque bullying is close to leaving his earthly life, but despite all this, Jesus’ tired face radiates forgiveness and human love.

Giotto’s Jesus is emaciated, at least compared to the more fleshy and muscular bodies depicted by Donatello and Brunelleschi. The latter’s Jesus, however, seems to be slimmer built than Donatello’s. Brunelleschi’s Christ has the same bent legs as Giotto’s, while the stretched legs of Donatello's Jeusus figure rest more heavily against the stem of the cross. Brunelleschi’s Christ has a small crown of thorns, though like Giotto’s Jesus, Donatello’s is lacking one.

It is in the expressions of their faces that the biggest differences between Donatello’s and Brunelleschi’s versions of the crucified Jesus become most apparent. It may be an illusion, though I assume that Donatello’s Jesus is closer to us than Brunelleschi’s Christ, with his tired, but still gentle gaze under almost closed eyelids, a half-open mouth with a swollen upper lip. His more prominent cheekbones and high forehead. The face, despite its lack of external damage, seems to bear witness to how an ordinary person exposed to contempt, betrayal and grotesque bullying is close to leaving his earthly life, but despite all this, Jesus’ tired face radiates forgiveness and human love.

Jesus’ heavy body lacks in Donatello’s rendering the slender elegance of Brunellschi’s personage. Like in Donatello’s version, Brunelleschi’s Jesus does not present many signs of having been brutally beaten and abused. However, in comparison with Donatello’s Jesus he has an air of refinement and sensitivity. A true aristocrat, or rather a superman’s submissive resignation under God’s omnipotent will. His eyebrows are sharply defined, the nose narrow and the cheeks soft and smooth.

Donatello's Jesus is closer to us in the sense that he endowed with the build of a manual labourer, like the construction worker Jesus probably was before he was convinced that he had a God-given mission (the Greek word tektōn the term used for Jesus’ occupation could mean craftsman, in the sense of a builder working with both wood-work and stone masonry). His figure and face indicate signs of the everyday life of such a man, with all the brutality and closeness to life that seems to be lacking in Brunelleschi’s nobleman. Vasari’s account of Brunelleschi’s judgment is to this extent entirely correct. Donatello’s Jesus is indeed reminiscent of a peasant, someone who has not only been crucified according to the Gospels, but furthermore been subjected to mob violence and the street contempt shown to powerless and/or deviant people.

Why does Vasari, while comparing him with Brunellschi's representation, seem to underestimate Donatello’s Jesus? Perhaps because Vasari in all the artist descriptions emphasized his appreciation of an artist’s ability to link physical beauty with creative skill and thus succeeded in imitating God’s creative power and originality in his/her works.

According to Vasari, a skilled artist is, unlike a farmer, a Creator, someone who, in accordance with the words of the Book of Revelation: “And he who was seated on the throne said, ‘Behold, I am making all things new’” mirrors God’s creative and innovative powers. A view that was not at all unusual among Renaissance intellectuals who often saw themselves as more than farmers. They were “citizens”, townspeople who, unlike the down-to-earth peasants, could appreciate the subtleties of philosophy and religious faith, far from the superstition and brutality that prevailed among the toilers of the earth. In fact, many Florentines harboured a deep-seated distrust and even fear of the peasantry who surrounded the city. In his Ricordi, Memoirs, Donatello’s contemporary, the wealthy cloth merchant Giovanni di Pagolo Morelli, stated that “there is no single peasant who would not be willing to come to Florence to burn the city down.” In other words, in an early work such as the crucifix in Santa Croce, Donatello already sreveals his skill in reshaping the art that dominated his time, in a new, revolutionary and life-like manner.

After finishing his crucifix, Donatello goes from strength to strength. Constantly varying and deepening the possibilities of his studies of ancient art combining them with an awareness of the innovations made by his contemporary artist colleagues. The powerful patron Cosimo de Medici caught sight of him and during his long life, during which Donatello was feverishly active until the end, he was never without constant, new assignments. In addition to his superb skills and unexpected gifts, Donatello, unlike many other artists, was known to be a modest, kind and extremely generous person.

It is through the subtle characterisation, the vitality and psycholgical depth of his motifs that Donatello has been hailed for an undeniable mastery. Shortly after returning from his study trip to Rome in 1433, in the company of Brunelleschi, Donatello created in Santa Croce his Annunciation, as a monument for the family tomb of the powerful Cavalcanti clan.

The angel and Virgin are executed in high relief in front of a partially gilded background in the form of a closed gate. They are depicted in the moment just after Gabriel’s appearance. The Virgin, placed in front of a lyre-shaped chair, has risen in surprise after sitting reading a book, which she still holds in her hand. The youthfully beautiful Madonna puts one hand to her chest and her graceful, gothically curved figure vaguely suggests that she has for a moment intended to escape from the apparition. The exquisite drapery of the dress follows the movement of the legs to the left, out of the picture, but at the last moment the maiden has controlled her emotions and turned towards the angel.

Gabriel kneels in front of the Madonna, who he almost shyly looks up at. It seems that with his slightly turned head, humble appearance and searching gaze, he wants to capture Maria’s unconditional attention. The scene breathes a bright, lively interplay between the portrayed figures, who animate their emotions with gestures and facial expressions. Donatello has succeeded in giving Maria’s nobly refined face an expression of quiet surprise, marked by both gratitude and humility.

Donatello avoided traditional elements such as the dove of the Holy Spirit and the lily, or olive branch, in the angel’s hand. The symbolic language is limited and subtle, like the book of Mary alluding to the Bible’s predictions about the coming of the Messiah and the closed gate in the background, suggesting the chastity of the Madonna.

Donatello never repeats himself and constantly surprises. Five years before the Annunciation in Santa Croce, Donatello, together with his colleague Michelozzi, had executed a sumptuous funerary monument for the still living Cardinal Rainaldo Brancacci. Brancacci was a sly, political vane and it appears rather strange how ecclesiastical princes like him could have the audacity to like ancient pharaohs erecting extravagant memorials over themselves. So be it, because after all, we have such self-adoring narcissists to thank for the astonishing masterpieces of several Renaissance geniuses.

I

On the Brancacci sarcophagus, Donatello executed one of the stiacciatore reliefs admired by his contemporaries. Stiacciato is a technique that makes it possible for a sculptor to create a so-called recessed relief with a depth of only a couple of millimeters. To gradually reduce depth from foreground to background an illusion of greater depth is created. Donatello must have learned this technique from his master Ghiberti, who used stiacciato in his occasionally depth-perspective reliefs on the famous Paradise Gates of the baptistry of Santa Maria degli Fiori

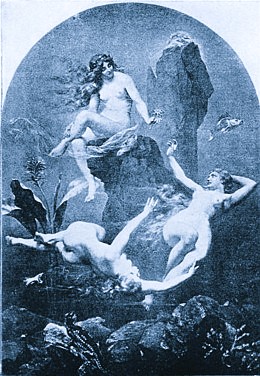

In his Ascension of the Madonna, Donatello portrayed an elderly, perhaps tired and worried woman surrounded by gracefully hovering angels. I come to think of the whirling of the Rhein daughters in the introduction to Wagner’s Das Rheingold.

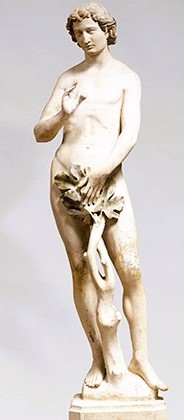

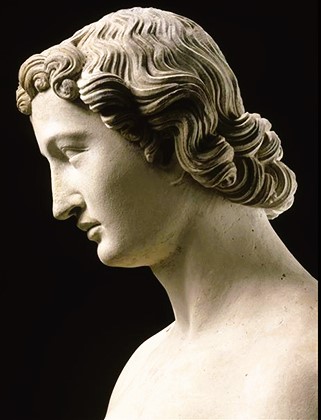

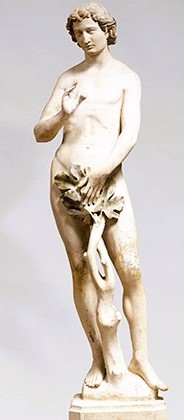

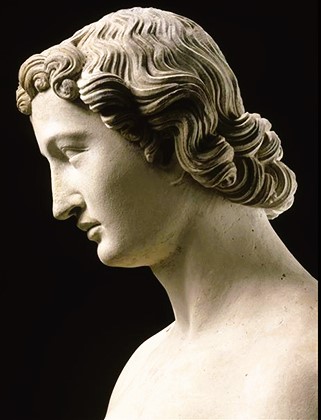

Returning to Florence, Donatello created several portraits in the Roman Antique style, difficult to distinguish from Greek and Roman models.

Or penetrating, highly original studies of contemporary men:

For one of the niches in Giotto’s tower next to Santa Maria del Fiore, Donatello executed an Old Testament prophet – Habakkuk. The gloomy and tormented man who called out to God with the lamentation:

How long, Lord, must I call for help, but you do not listen? Or cry out to you, “Violence!” but you do not save? Why do you make me look at injustice? Why do you tolerate wrongdoing? Destruction and violence are before me; there is strife, and conflict abounds.

The misanthropic man depicted by Donatello and popularly called Il Zuccone, the Bald One, had as its model a now forgotten artist, wealthy man and opponent of the Medici family – Giovanni de Barduccio Cherichini. The sculptue became immediately popular among the Florentines, who were taken by the old man’s serious attitude, as well as the great skill and realism with which the statue had been executed.

Vasari states that it was Donatello’s favorite work, and that he got into the habit of swearing his oaths by saying: “By the faith I have in my Zuccone,” and that while he was working on on the statue he would look at it and keep muttering; “Speak, damn you speak!”

Donatello increasingly distanced himself from the fashions of his time. His insightful studies of well-known saints became increasingly realistic and unexpectedly bold. As an aged and worn-out Mary Magdalene depicted in all her frailty, with an emaciated body, wated through devastating penance.

So different from his St. George, which was commissioned by the armourers’ guild to adorn their niche in the Chiesa di Orsanmichele. The niche Donatello was assigned was unusually shallow and thus the sculpted a figure that partially emerges from it and it can thus be seen from several directions.

It is an individual who steps forward, alert and tense. St. George has not yet attacked the dragon, which presence spectators sense behind their backs. The warriuors’s feet rest firmly on the ground, but his right foot is slightly extended and the posture thus harmonizes with St. George’s worried facial expression. He does not exude defiance and can hardly be assumed to guard anything. His shield is at rest, but we nevertheless get an impression of courage and determination. A determined preparedness for a difficult task that could have a fatal outcome for himself.

As expected, St. George is encased in a sinuous and exquisitely chiselled shell of leather and metal, after all it was the armorers’ guild that hade commissioned Donatello to create a bold and heroic Saint George. Despite this, there is an air of defenselessness about the lonely saint, well aware as he is of the great danger he will soon be exposed to. However, this does not prevent his whole figure from being characterized by a nervous energy. We are unsure how long he will sustain this tension. Soon he must attack, … or retreat.

Nervousness and hesitation characterize the tense face; the furrowed brow and the worried look. Unlike Donatello's marble David, St. George is in his niche almost level with the viewer who can thus be directly confronted with his anxious preperaedness. Soon he will overcome all his doubts and thus becomes an image of one of the virtues that the Florentines liked to attribute to themselves – Prontezza, an ability to be prepared to face every threat and adversary with elevated calm.

The relief under St. George is executed in exquisite stiacciato through which the loin of his horse appears to be closer to the viewer than its head. The dragon, St. George and the Virgin, who is rendered in elegant Gothic curvature, are sharply plced against a central perspective background, where the wild nature, which cliffs and caves are the dragon’s home, are juxtaposed to the ordered, urban landscape behind the Virgin – culture and order in contrast to the unbridled evil of nature.

Soon Donatello utilized the stiacatto technique for increasingly sophisticated representations. With a background of symmetrically constructed areas created through a perspective combined with empty surfaces, he harmonizes the actors with a space that both encloses them and opens behind them. Dramatically concentrated, and at the same time dynamic depictions that as in snapshots captures eventful processes, through which emotional energy is reflected through the actors’ body language.

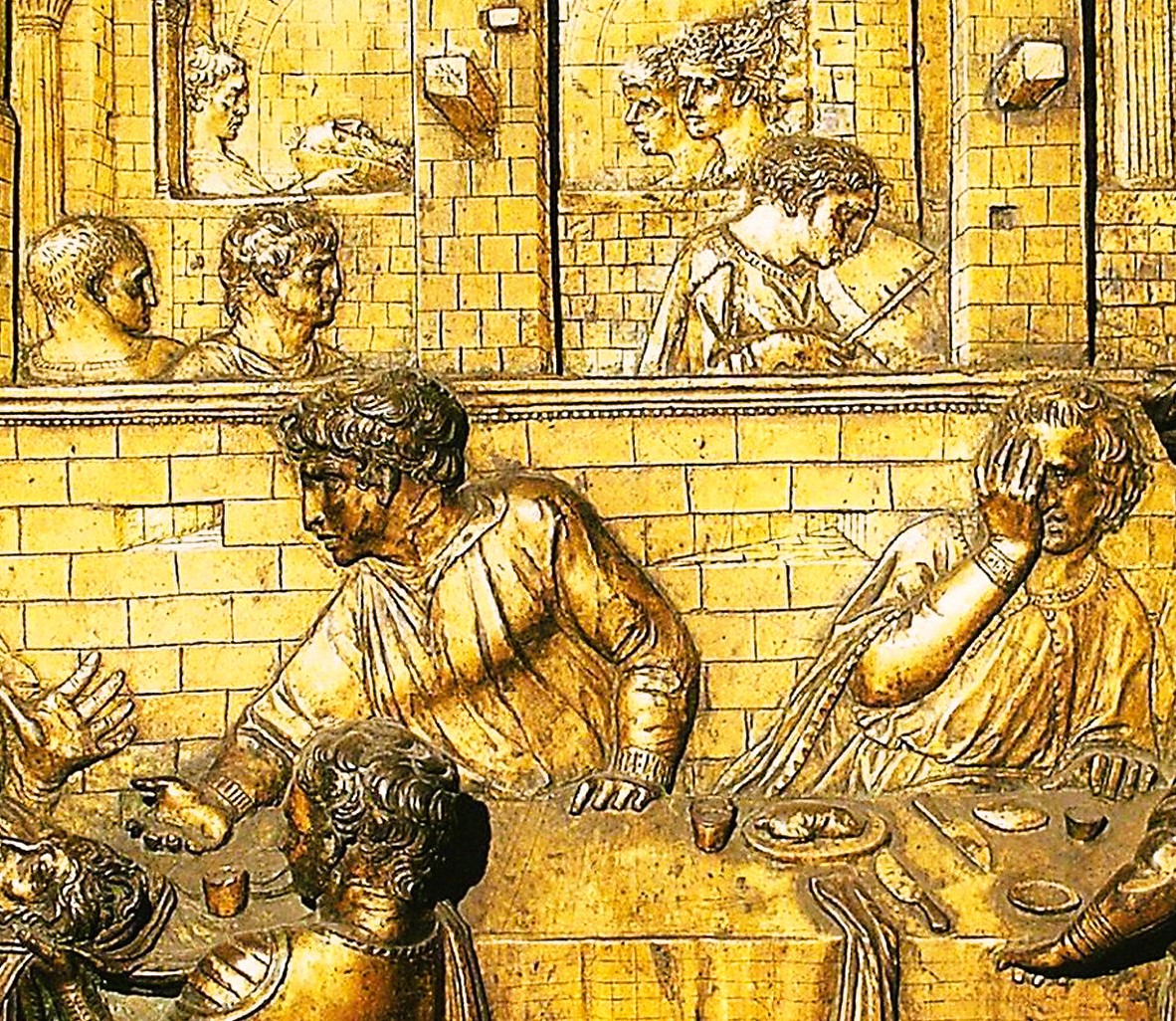

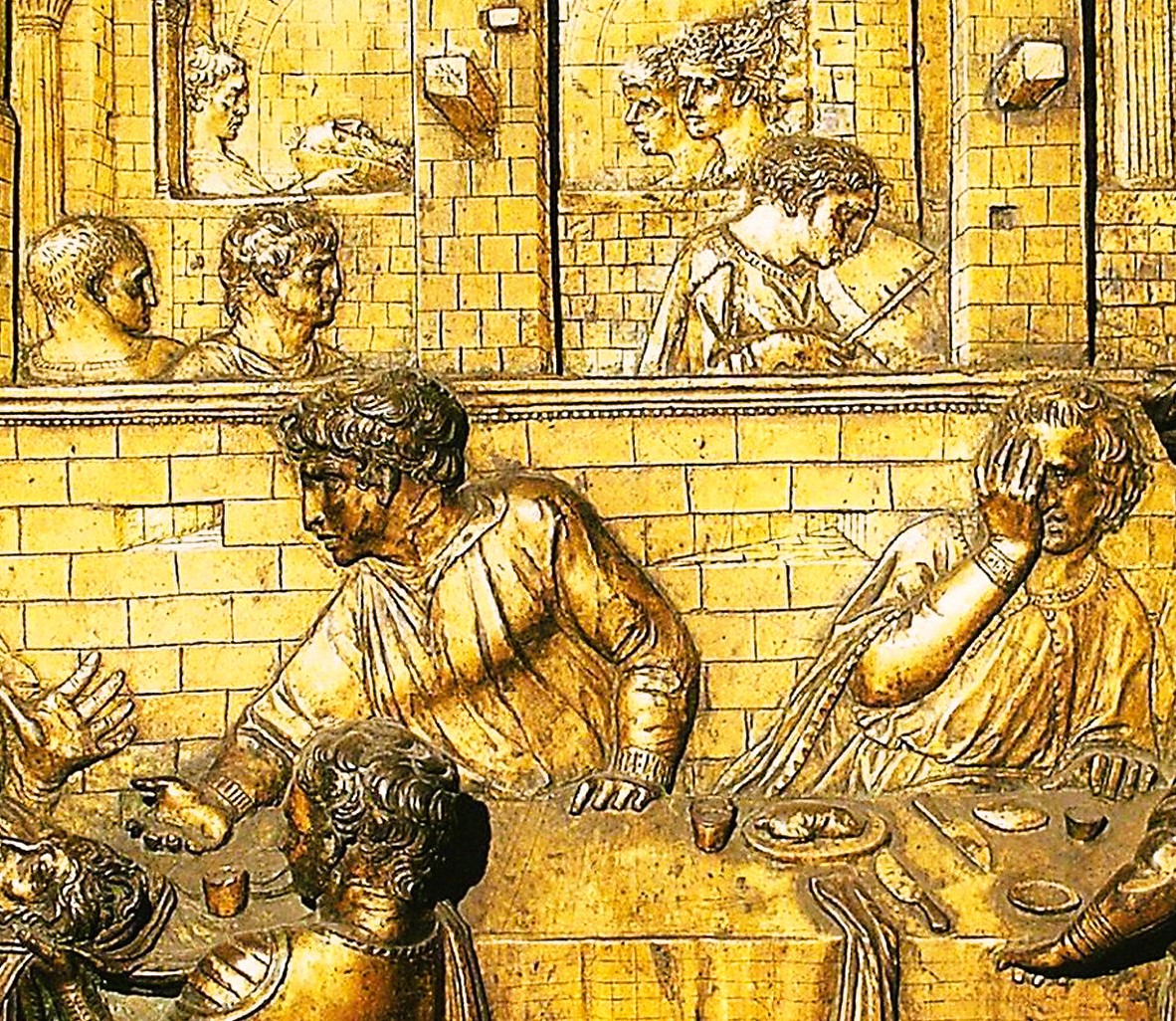

A relief on a baptismal font in Siena shows the turbulent scene when a kneeling executioner during a banquet on a plate is handsing over the severed head of John the Baptist to Herod. The drama of the main incident is strongly emphasized and psychologically nuanced. The various reactions to the blood-stained head are reflected as captured in a wave of horror and disgust, which to the right subsides around an unaffected Salome who seems to have just finished her fatal dance.

The depth of the image is divided into several planes – foremost where the executioner holds out the dish with John’s severed head, small children flee at the sight of the terrifying head while the unemotional Salome in a pleated dress that seems to refer to the wild dance she previously has performed before Herod

The other side of the table forms another plane in which Herod recoils in disgust when he is offered grotesque of a severed head, while his wife Herodias, with a giving gesture indicates the cut off head she has persuaded her daughter to request from her stepfather as a condition for perfroming her arousing dance. A void has opened up around Herodias and her explanatory attitude, her nasty request has aroused disgust and repudiation among those around her. At the other end of the table, one of the diners covers his face with one hand as he turns away in repulse of the bloody spectacle.

On a plane behind these people we glimpse the musicians who have accompanied Salome’s dance and at further away we glimpse how the executioner hands over the head of John the Baptist to Herodias and her daughter. The lively, and highly original, presentation of a commonly known scene probably shocked the spectators who were confronted with it. There was no elegant sophistication here, but an unprecedented brutal realism. A flash of presence through which the artist conveyed an impression that he had actually witnessed what he described.

Donatello did not only use the stiacatto technique to present crowded and dramatic scenes. He also created intimate, devotional setting, such as this one where a deceased Jesus is lifted up by mourning angels.

Or a number of sensitively depicted Madonna images reflecting a tender love between mother and son.

On an exterior pulpi by the facade of the Cathedral of Prato, he depicted a joyfully unrestrained horde of dancing little angels. Such pulpits were used by famous preachers who, like rock stars, moved from town to town and attracted large audiences through their virtuoso preaching

It is difficult to imagine how austere orators and sombre revivalists preached their deeply religious messages of divine punishment and Christian restraint from a rostrum adorned with bacchanalian, dancing cherubs.

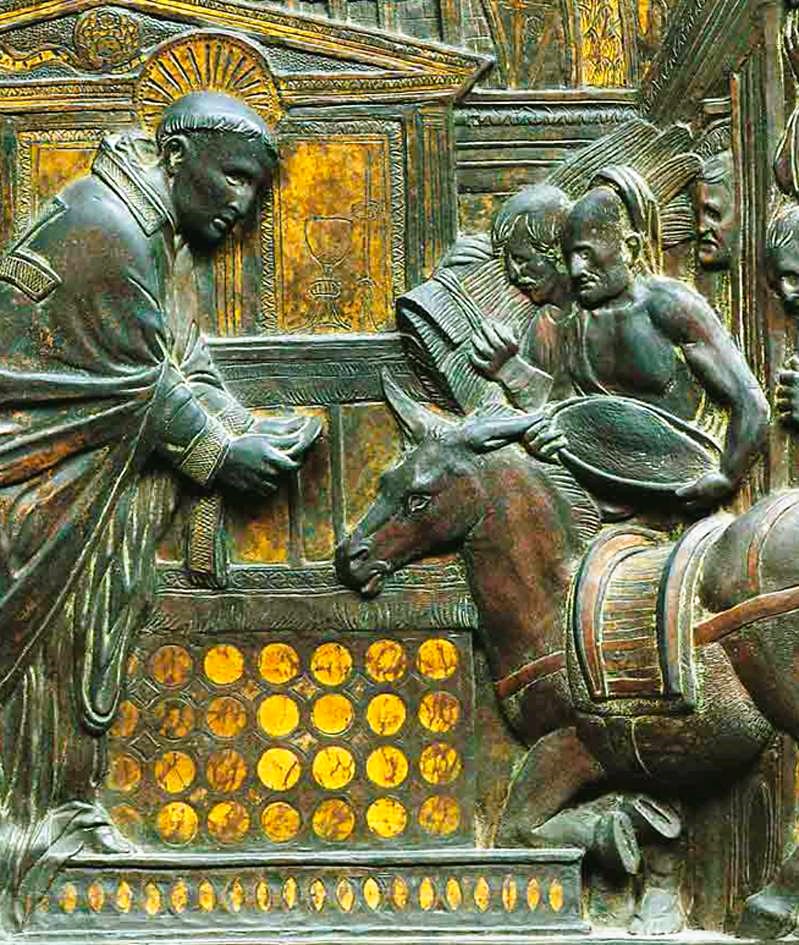

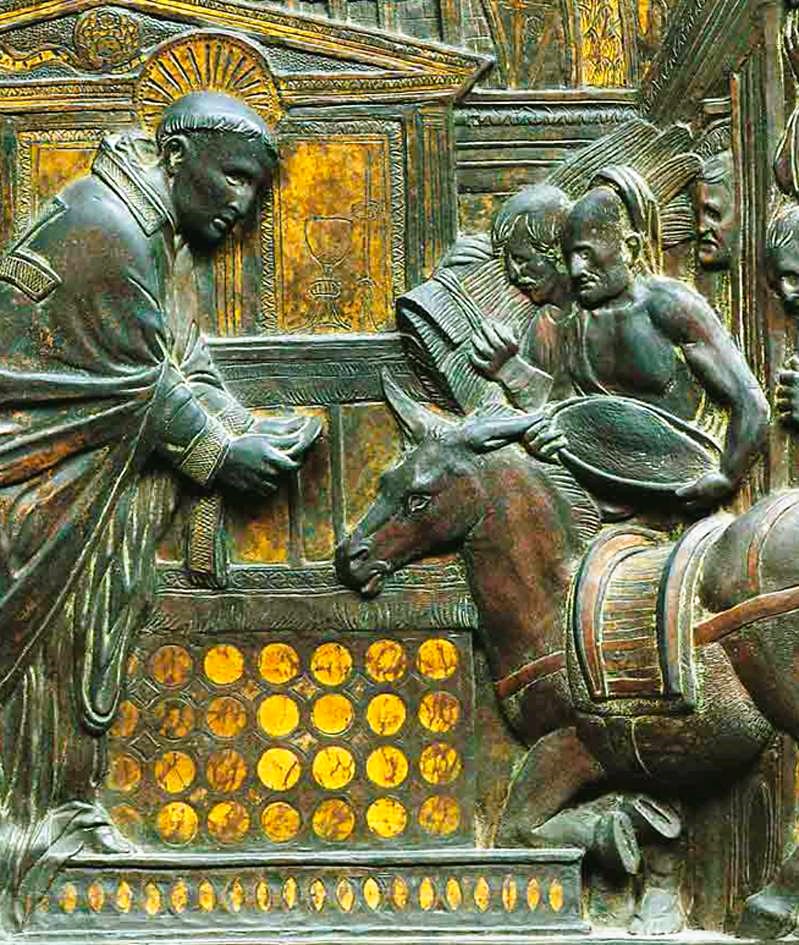

Inside the slightly congested basilica of Padua, Donatello gave vent to his original and imaginative art. Behind the high altar we find, for example, a representation of one of Sant Antonio’s miracles. In its scenic grandeur it reminds of some historical cinemascope film produced in Hollywood. The cinematic impression once again provides an impression that Donatello actually witnessed the vivid scene he is rendering.

What Donatello illustrates is a somewhat silly, but at the same time politically cahreged legend. The Pataria was a 11th-century movement aiming at reforming the clergy by enforcing papal sanctions against simony, challenging clerical control of the Eucharist, as well as it tried to outlaw clerical marriage and concubinage. The movement caused some armed rebellions which were soon put down and Pataria eventually was declared to be an open and punishable heresy.

According to legend, a miller named Bonvillo denied the celestial and miraculous nature of the Eucharist, namely that the belief that during Mass the wine and bread actually were transformed into real flesh and blood. He challenged San Antonio by keeping his mule confined for days without feeding her. Then he would take her to the square in front of the catedral and a multitude of people and put some tasty fodder in front of her. At the same time, San Antonio would rise a consecrated oblate for the mule to see. If the animal knelt before the host and ignored the pile of clover and other appetizing things, Bonvillo promised that he would never again utter any disbelief in the miracle of the holy mass.

Antonio accepted the challenge and on the agreed day the saint showed the host to the mule with the words:

If indeed what I hold my hand is the human fleash of our Creator, I command you, dumb animal, to humbly approach Him and show Him due reverence.

Scarcely had Antonio finished his sentence than the mule, to the astonishment and jubilation of the people, ignored the appetizing food, bowed her head and knelt before the sacrament and incarnation of Christ’s body.

Perhaps a certain humor can be sensed through Donatello’s large-scale representation of of a multitude of the people showing astonishment at the miracle of the kneeling mule.

Among the evangelist symbols that also adorn the main altar of the Basilica San Antonio di Padua, the lion of Mark undeniably makes an amusing impression, humanized as it is with an individualized expression of concentration and authority.

The Madonna, enthroned in front of the altarpiece’s crucifix, stands in front rather than sits on her throne. She appears to be leaning forward, an impression reinforced by her thrusting head which lends intensity to the forward movement. She holds the baby Jesus in front of her, as if she wants to demonstrate it to the congregation. The chubby child turns to us with a gesture and facial expression that seem to free him from his mother’s hold. The treatment of the bronze is exemplary – shiny, smooth and hard.

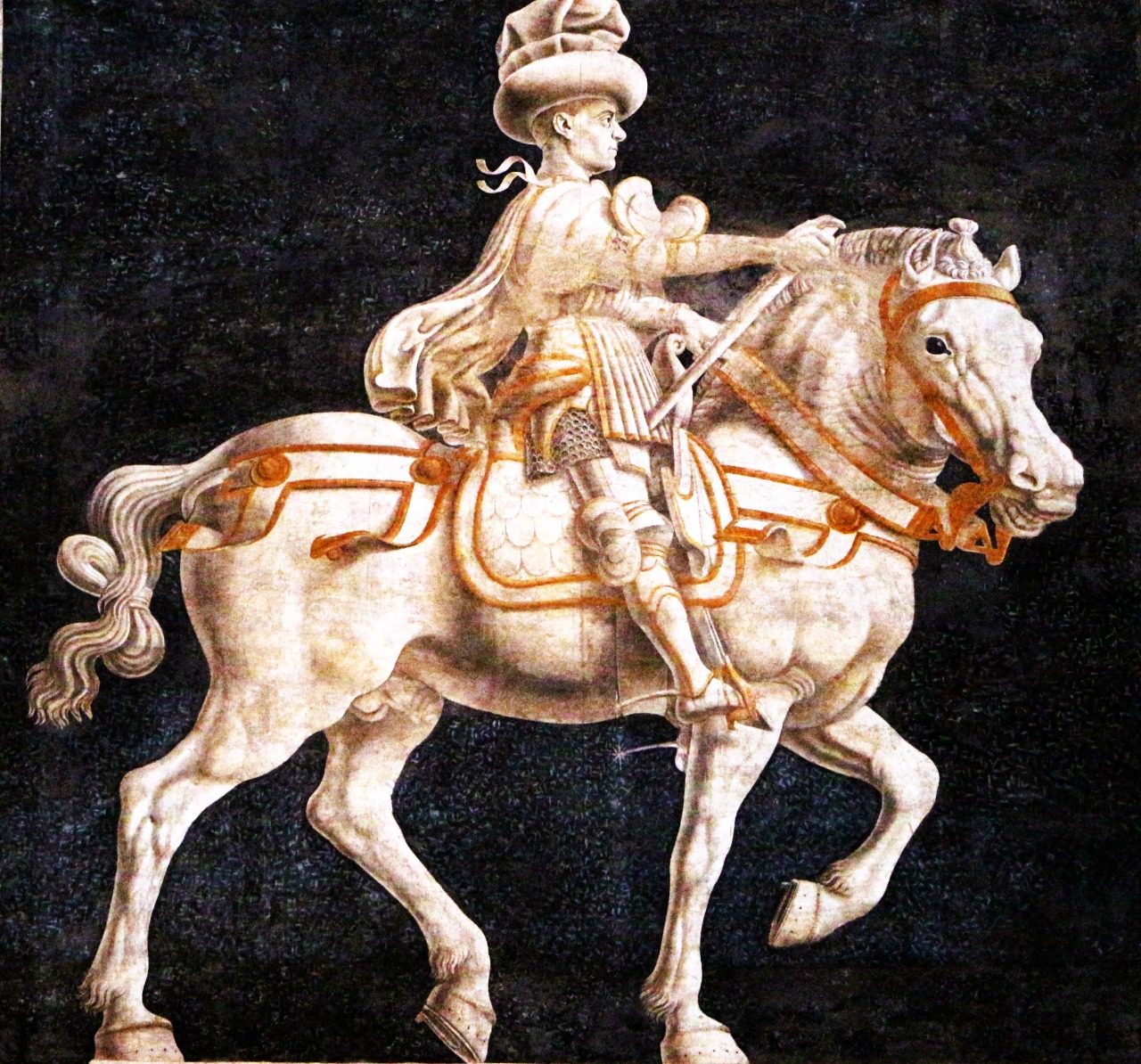

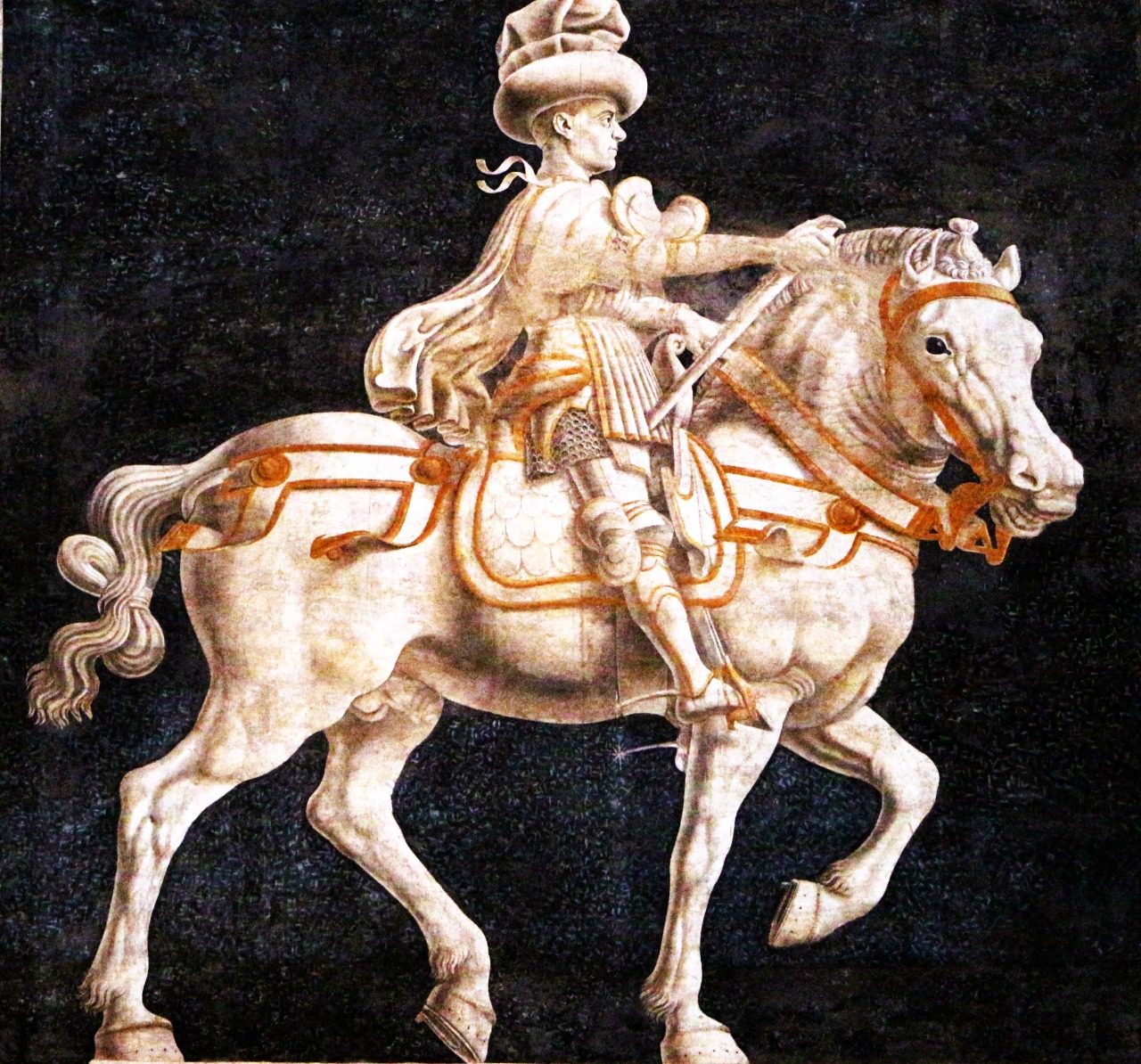

Right next to the Basilica di San Antonio, the condottiere Erasmo Stefano da Narni, called Gattamelata (the Honey Smoth Cat) is in a powerful manner urging his magnificent steed forward. In earlier (painted) equestrian depictions, of which Ucello’s and del Castagno’s frescoes are the most famous, the huge horses appear to be more prominent than their riders.

With the ancient Roman equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, who was probably Donatello’s main model, the roles appear to be reversed. The horse is truly magnificent, though the emperor seems to outsize it.

Gattamelata’s horse exudes calm and massive power. The general’s posture and facial features express confined, but intense activity. His grim expression does not indicate any unleashed warrior frenzy, but rather careful calculation, control and concerted preparedness.

.jpg)

In his sculpture, Donatello has depicted Gattamelata as he leads his troops during a battle. Command staff and sword form a diagonal that cuts out the commander at an angle to the plinth, thus drawing the viewer’s attention to his reflection and overview. Compared to previous equestrian statues, there is a realistic renewal here, a dignity and formal effect that is nevertheless based on previous representations.

Donatello made several detailed horse studies and in Naples there is a magnificent horse’s head which, in the exhibition in the Palazzo Strozzi was placed next to a copy of a head from the four ancient bronze horses that adorn the facade of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice. They had been stolen from Constantinople in 1204 and since then thay have been an inspiration for various artists.

Gattamelata is a free-standing sculpture, one of the few previously created after Roman Antiquity. In many ways, Donatello's revolutionary art was a renewal of ancient Roman-Greek art, which has made some art connaiseurs to believe that some of his art works actually originated from ancient Rome. However, not his most famous work – the free-standing bronze sculpture of David.

As of 1437, the Medici were the most influential family in Florence and largely controlled the city and its Signoria. For several centuries, the Medici gathered at their court Italy’s foremost artists, writers, humanists and philosophers. Of course, this gave glory and prestige to the increasingly powerful and wealthy Medici clan, but possibly their patronage of art, music and literature could also be considered a gesture of appreciation of their hometown and its citizens.

Donatello was held in high esteem by Cosimo de Medici, the leading man of the Florentine moneyed aristocracy, who assumed an unofficial position as ruler of the city republic. In 1440 he ordered from Donatello a “free-standing statue”, a figure in the “antique” spirit, completely sovereign, unbound by any decorative tasks.

.jpg)

The result was astonishing. Donatello’s David was placed in the garden of the Medici Palace and its shocking originality aroused astonishment and admiration. The heroic youth is almost completely naked, and it is only Goliath’s fearsome, armored head at his feet that suggests this is the David of the Old Testament and not some Greek god.

With an enigmatic smile, the elegant youth poses with one foot on Goliath’s severed head. It is the moment after his defeat of the giant. The boy has a strong physique, though provides the spectator with a remarkable “feminine” impression. David’s slender build contrasts with the large sword he holds in his right hand.

His nakedness suggests that David defeated Goliath not through physical strength but due to God’s intervention. This is not the case, as it was with Donatello’s St. George of a moment of vigilance and nervousness, but about relaxation and reflection. The young man’s face is calm. His facial muscles are completely relaxed and a mysterious smile plays on the slightly open mouth. There is a subtle pride in his expression, not boastfulness but rather a reflection of inner thoughts. We are not confronted with a triumphant superhero holding aloft a sword and a severed head. Instead, we meet a contemplative face and relaxed body.

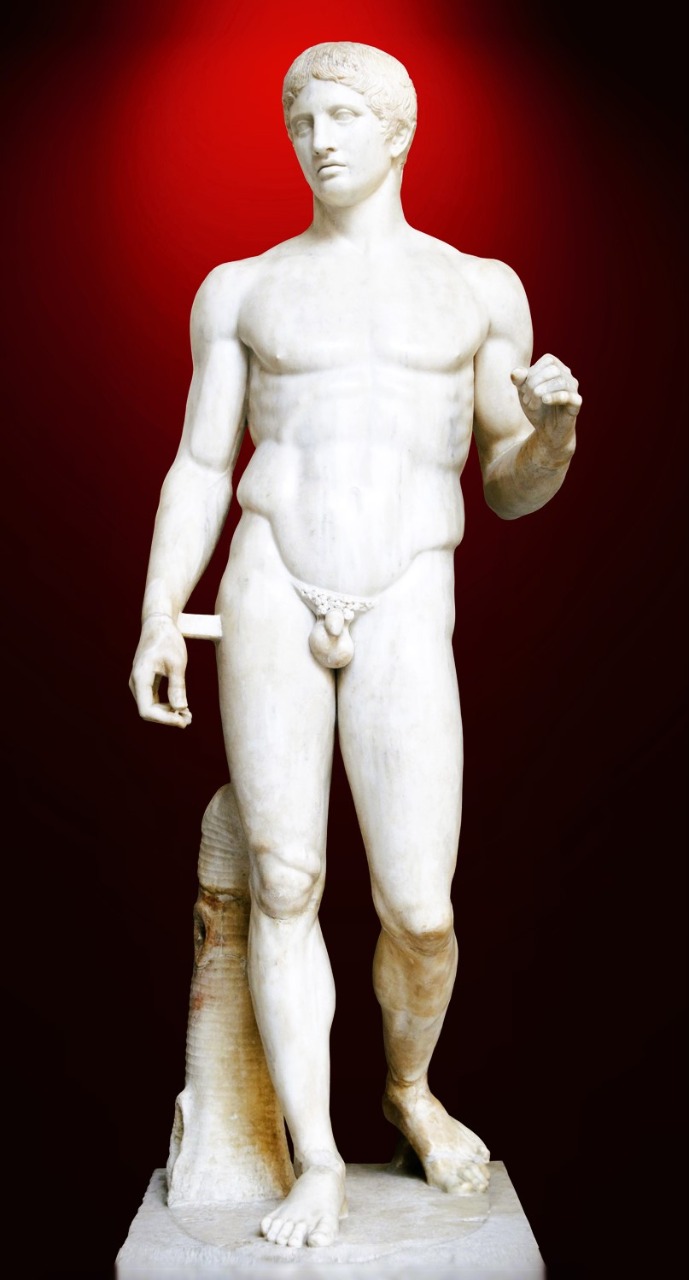

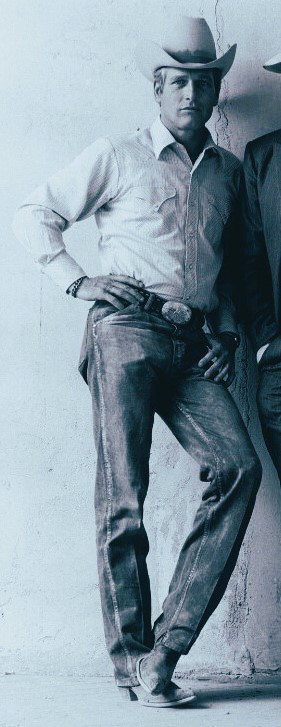

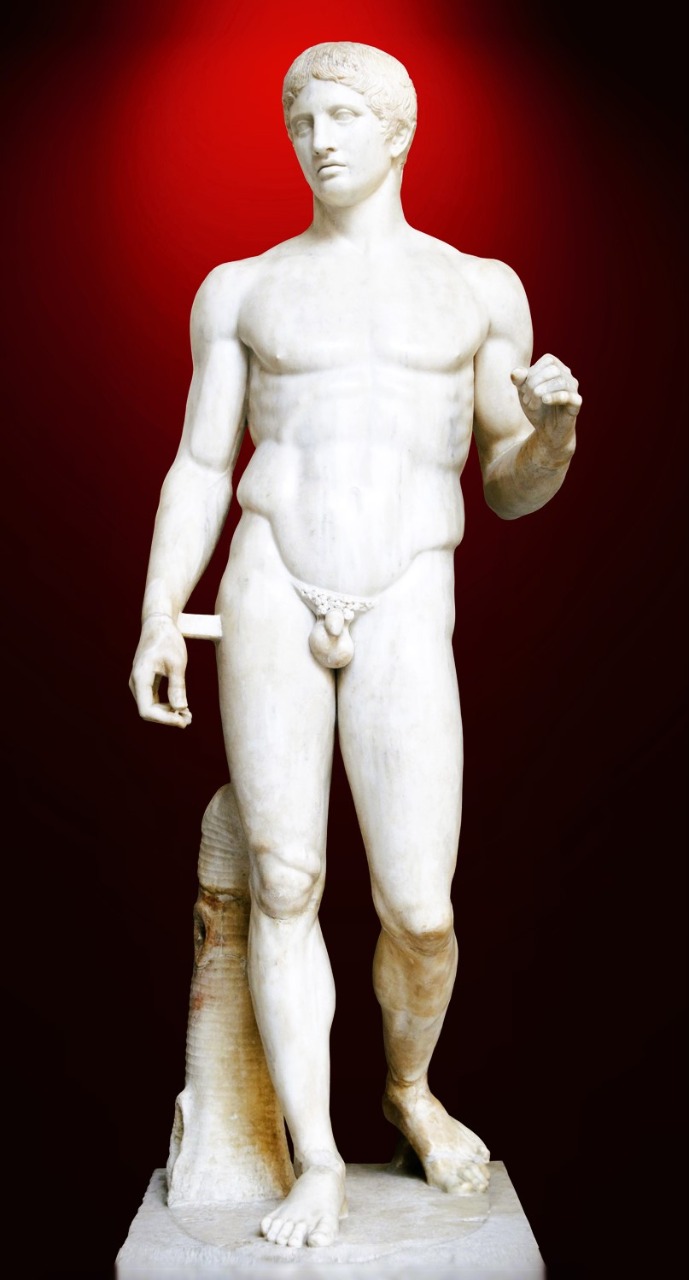

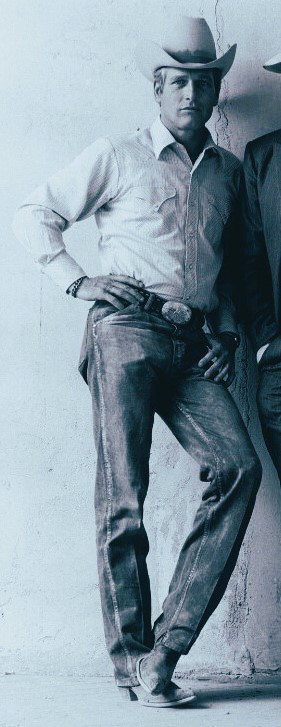

The body position indicates a calm confidence. David rests standing, seemingly carelessly, but nevertheless harmoniously, with the weight placed on the right leg. It is a classical counterpose, well known through Polykleitos’ Doryphoros, Spear Bearer, which since its creation in 440 BC. has been admired and copied as the epitome of harmony, dynamism and balance. Not least in poses taken by modern film actors, such as the young Marlon Brando and several other Hollywood stars.

At the same time, in Donatello's David there is something of the sliding line rhythm of the Gothic, from the brutally severed head along the body up to the shoulders and the long hair. A gliding upward movement that meets and interacts with gently falling rhythms in the hat, arms, crotch and legs. A continuous pulse seems to run around the entire sculpture, a constant succession of clearly chiseled silhouettes around hard, solid matter. Freed from all supports and surrounding ornaments, structures and contexts, an individual appears, who with a unique physicality, allows himself to be viewed from all angels. In my opinion, Donatello’s David is far more harmonious and complete than Michelangelo’s more famous and admired free sculpture of the young David.

The tradition-breaking, uniqueness, but still antique-applying quality of Donatello’s David has made several “experts” declaring it to be the first free-standing sculpture in history after Antiquity and a kind of talisman for the Renaissance. An opinion I perceive as an example of a coomon, casual condemnation of the greatness of medieval art. I do not see the Renaissance as a break with earlier art, it is rather a superb part in an unbroken chain of masterpieces. The psychological depth Donatello conveys in his art is also present in medieval artwork.

On our walk to Donatello’s David in the Bargello Palace, we passed several exquisite Byzantine ivory miniatures. This meticulously executed craftsmanship, with its perfect dynamics and harmony within confining spaces, reminded me of an ivory miniature made in Lorraine sometime in the 11th century that I in 1973 first saw in East Berlin’s Bode Museum and I since then I have often thought about it.

The figures are pressed against each other in a round-arched niche. The ivory carver has masterfully arranged the entire image surface and balanced Thomas the Doubter and Jesus against each other with perfect clarity, rhythmic power and saturated expressiveness. With his back to the spectator, the Doubter climbs upwards while he clings to Jesus. In anguish and doubt, he tears at Christ's mantle and with his fingers dig deep into the exposed wound. Thomas’ intrusive clinging is contrasted with Christ’s calm. With raised arm he exposes his wound and harmoniously fills the roundel of the niche while he is serenely watching the upset Tomas. Jesus exoresses concerned participation, patience and pity. Here, through gestures and interplay, there is profound psychology at play, just as in Donatello’s best works.

Perhaps one might consider medieval crucifixes as free-standing sculptures. For example, Helmsted’s bronze crucifix from the latter part of the 11th century,

or Bishop Gero’s crucifix in the Cologne Cathedral. Carved sometime between 970 and 1000, it is history's first preserved, wood-carved monument and already perfected in its representation of Jesus’ already dead and prostrate body.

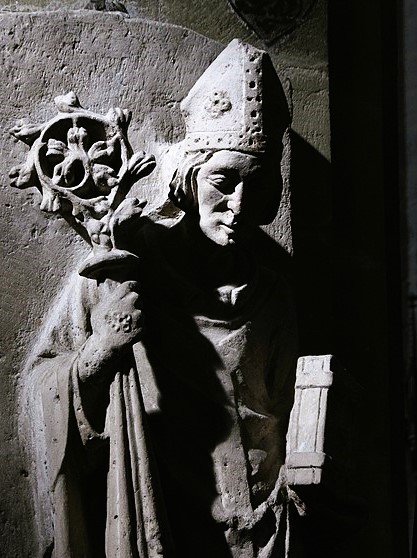

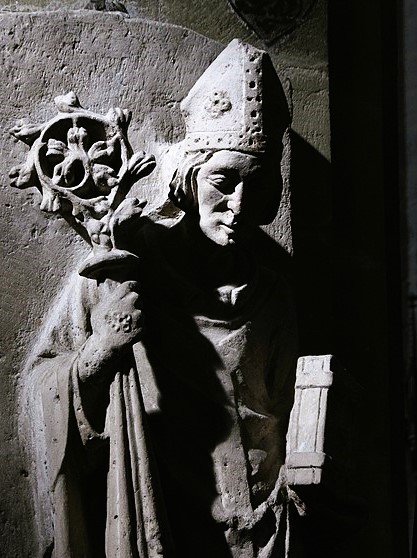

The statue of St. Teodore in Chartres gives an heroic an impression similar to Donatello’s St. George.

Pierre de Montreuil’s Adam from the begiining of the 13th century, which is now in the Musée de Cluny in Paris, can actually be considered as a free-standing sculpture, produced in a perfect Greek-Roman antique spirit.

The Defeated Synagogue in the Strasbourg Cathedral is as poignant psychological study as those created by Donatello.

So are the prophets of Bamberg. Jonah’s face bears comparison with Donatello’s Il Zuccone.

The Rider in Bamberg is certainly not as dynamic as the Gattamelata sculpture, but is nevertheless endowed with a calm and noble grandeur.

Uta von Ballenstedt in Naumburg has a mysterious and withdrawn air about her and thus stands in stark contrast to the wonderfully realistic representation of the lush and happily smiling Queen Adelaide of Burgundy, made 1260 in Meissen, although it looks so fresh and new that I doubted whether it could actually be that old.

The lively relief of the Last Supper in Naumburg is as skillfully executed and varied as any of Donatello’s reliefs.

Bishop Hohenlohe’s imgae from 1350 in the Bamberg Cathedral leans towards us and like the figures in Donatello’s artwork he provides us with a vivid, unique and idiosyncratic impression.

Despite a realisation of the greatness of medieval art, I nevertheless dare to say that Donatello’s contribution is both different and revolutionary. His astonishing blend of tradition and modernity was, after all, something entirely new.

Medieval artists never ceased to seek inspiration from the sources of the classical art of Byzantium and Rome, though their output was overshadowed by a spiritual outlook. A presentation of ideal conditions, largely disconnected from Antiquity in the sense that Augustine gave as the task of art – uti non fruti, to use but not enjoy. The medieval Christian ideal of God allowed the flesh of Antiquity to be resurrected in a declared form, purified in the fire of faith, bearer of a message about the Kingdom of Eternity beyond the limits of the visible.

Contrary to such a mindset, Donatello’s work has a worldly anchoring. Even when he portrays saints and madonnas, he does so in a personal and intimate way. A reality seen through a temperament and sometimes, as in the statue of David, he lets himself loose in a way that seems to be completely freed from Judeo-Christian tradition and thinking.

In the exhibition in the Palazzo Strozzi, one of Donatello’s strangest works was exhibited on a pedestal. It was for a long time widely considered to date from Roman Antiquity, although Vasari and some of his contemporaries carrectly identified it as a work of Donatello. Vasari describes the sculpture as:

a bronze Mercury, standing three feet high in full relief and clothed in a curious fashion.

Cupido-Attys is undeniably bizarre. A remarkably skilfully made study of a child’s body, whose proportions, contrary to medieval methods of representation, cannot be considered to be those of a miniature adult. Part of the puzzling character of this statue originates in the juxtaposition of a variety of classical motifs—wings like a cupid, a small goat's tail like that of a faun, winged sandals like those of Mercury, and what seems to be an allusion to the Bacchus Child and other fertility-suggesting creatures which during Antiquity, often were depicted in the form of babies, cupids and putti.

The strange clothing that exposes the boy’s genitalia, the raised arms and above all the face, where the burnished bronze, chubby cheeks, dimples, a half-open, smiling mouth – all this gives an impression of movement, a fleeting, excited feeling allluding to ancient models of bacchanalian, unrestrained freedom, expressed in the raised arms and the swinging, dancing movement.

However, even though the statue has been interpreted as an expression of the free-spirited joy of the Renaissance, by me it provides a sneaking sensation of unease. Through the strange pants that expose his genitals and the boy’s vitality, his apparently cheerful liveliness, the whole arrangement seems to be charged with an ill-concealed erotic energy, an air of distasteful pederasty. Behind Cupido-Atty’s consummate realism, the masterful execution of details, a sense of discomfort might be felt, something menacing, unhealthy and disturbing. The boy, in the midst of all his implied joie de vivre, seems able to do harm – to himself and others.

At the age of seventy-five, Donatello created a representation of Judith in the process of cutting off the head of Holoferenes. Judith stands upright, her sword is raised, while she with a firm grip on his hair lifts up the lifeless tyrant’s body. Calmly and methodically, she prepares to severe the brutal old man’s head from his body, acting with the calm of an everyday butcher. For several years, the sculpture was placed in front of the Signoria’s palace, as a symbol of the Republic’s contempt for autocrats and tyrants.

Donatello’s last masterpieces, executed when he was approaching the age of eighty, are the bronze reliefs on the so-called pulpits in the Florentine church of San Lorenzo. “So-called”, because these are probably not pulpits, but rather intended to be sarcophagi, even if were not used as such, but lifted up on pillars to be used by pulpits.

Vasari wrote that Donatello in the ned became increasinly senile, though there is not the slightest sign of this in the execution these reliefs, which are characterized by the same monumental realism as the altar reliefs in Padua. Hoever, here the realisim even stronger than before, perhaps even characterized by an old man’s disillusionment. As in the his representation of St. Lawrence’s martyrdom during which he with with a long pole attached to his neck by an excutioner is mercilessly ressed down into violently blazing fire. The spectators seem to be quite unmoved by the horrid spectacle. A Roman soldier holds his shield in front of him, as if to protect himself from the heat of the fire.

In another impressive scene, the three women descend to visit Jesus’ tomb. There they are met by an angel who announces that he has risen. The eldest of them seems to be clinging to a pillar, overwhelmed as she is by the startling message, while another woman, whose face is hidden by her cloak, with a lamp in her hand, descends the steps of the rock tomb. She seems not yet to have perceived the angel’s presence.

The reliefs are so high up that it is difficult to make out any details. I was amazed at the sight of a servant who, during Pilate's confrontation with Jesus, holds up the bowl of water in which the prefect is to wash his hands, a symbolic act to show that he is not guilty of the death sentence he pronounced. But ... with my neck strained, I tried to focus my gaze on the servant’s head. Did I see right? Did he really have two faces?

When I got home I rummaged through my art books and found that this was indeed the case. It looks as if Donatello was trying to create a sense of movement. With one facial movement, the servant calmly turns to Pilate, while the other seems to be turned to Jesus, in surprise at his presence or what he he saying.

The art historians I conulted commented on the double face by making a lot of comparisons with similar images, not least ancient Janus’ faces. It seems to me that they got lost in complicated explanation, which in at least two of them resulted in the opinion that the double countenance of the servant reflects Pilate’s hesitancy, his reluctance to make a firm decision and stick to it.

It may well be a plausible explanation. How, to me, Donatello’s double-faced servant might be a bold and successful attempt to create movement in art through duplication.

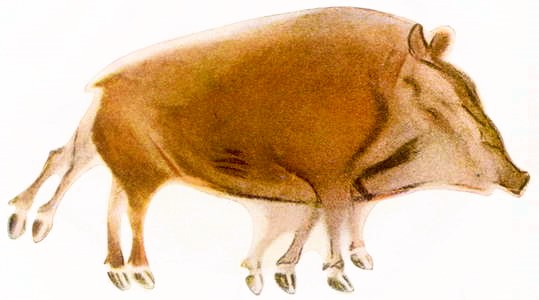

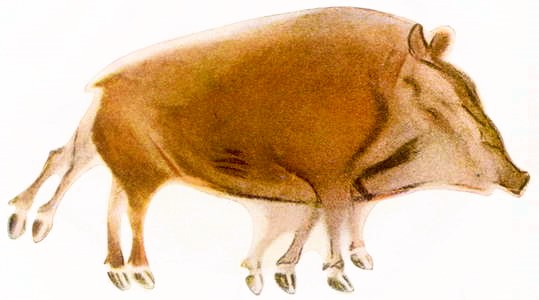

Already in ancient times, a Stone Age artist succeeded in admirably creating a boar’s gait in the Spanish cave of Altamira using a technique a technique of doubling features.

It would take thousands of years before Italian Futurists succeeded in creating a illusion of movement, like Balla in his representation of a dog’s brisk walk with its master. Or Boccioni when he fills the space of an entire painting with the illusion of movement, while the face of a woman leaning forward is doubled in what appears to be a window reflection.

Once again, one of my blog posting has grown beyond its limits. However, it was hard to hold back all the thoughts that my meeting with Donatello in Florence gave rise to. The realization of his modernity, vitality, inventiveness and unimaginable skill was undeniably staggering and will stay with me for a long time.

Vasari wrote:

He was superior not only to his contemporaries but even to the artists of our own time […] Artists should, therefore, trace the greatness of the art back to him rather than to anyone born in modern times. For as well as solving the problems of sculpture by executing so many different kinds of work, he possessed invention, design, skill, judgement, and all the other qualities that one may reasonably expect to find in an inspired genius.

Harris. Jim (2011) ”Defying the Predictable: Donatello and the Discomfiture of Vasari,” in Harris, Jim, Scott Nethersole and Per Rumberg (eds.) ‘Una insalata di più erbe A Festschrift for Patricia Lee Rubin. London: The Courtauld Institute of Art. Levey, Michael (1967) Early Renaissance. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books. Martina, Guido och Giovan Battista Carpi (1983) “Messer Papero e il Ghibellin Fuggiasco,” in Topolino, n. 1425, 20 marzo. Pagolo Morelli, Giovanni di (2019) Ricordi: Nuova edizione e introduzione storica. Florence: Firenze University Press. Pfeiffenberger, Selma (1967) ”Notes on the Iconology of Donatello’s Judgement of Pilate at San Lorenzo,” in Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 20, No. 4. Poeschke, Joachim (1993). Donatello and his World: Sculpture of the Italian Renaissance. New York: Harry N. Abrams. Vasari, Giorgio (1988) The Lives of the Atists. London: Penguin Classics.

DONATELLO: The world of a genius

Italy is an inexhaustible source of all kinds of unexpected experiences – culinary, as well as cultural. I open the door to something that has fleetingly interested me and impressions, memories, dreams and a host of other phenomena rush over me. Like when a month ago, together with my American friend Joe, I visited Florence and was confronted with Donatello’s art. An exhibition about his life, works and influence was presented in the palaces of Strozzi and Bargello.

I had previously visited Florence many times and in churches and museums been confronted with Donatello’s work, read about the Master and heard my art professor tell about him, but I had never seriously realized the extent of Donatello’s genius. The great and revolutionizing influence he had had on his followers. I once again realised the astonishing moment in human history during which he and his good friend Brunelleschi constituted the eye of the hurricane. Donatello with his sculptures and reliefs, Brunelleschi with his theories about the central perspective and the dome he created above Santa Maria del Fiore.

The two friends had visited Rome together, where Donatello had been overwhelmed by the presence of cultural treasures left behind by past times; the imaginative richness, balance and perfect harmony of the Greek and Roman statues and sarcophagus reliefs, this while Brunelleschi (1377-1446) in detail studied ancient arch techniques and immersed himself in the writings of Vitruvius (80-15 BC).

Brunelleschi was the more theoretically/mathematically versed of the two geniuses, while Donatello was a consummate artist/craftsman, with an intuitive sense of the expressions his art would take to satisfy his clients’ expectations, and more than that – astonish them. Donatello’s contemporaries often pointed to his lack of education, claiming that he was barely literate. I doubt if this is really true, assuming it was a myth intended to suggest that his genius was God-given, just as Muslims often state that Muhammad could neither read nor write, thereby implying that his teachings were forthwith dictated by God.

Donatello, actual name was Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi. Donatello is a diminutive, an epithet given him due to his small stature. He was born in Florence 1386, as the son of Betto Bardi, whose occupation was listed as “wool carder”, although he also occupied himself as goldsmith. Wool carder could mean that Bardi was a proletarian, though it could also mean that he was owner of a wool carder manufactory, something that seems to be indicated by the fact that he was a Guild Master. The guild he belonged to would then have been the powerful Arte della Lana, a craft association that included wool manufacturers and wealthy merchants involved in Florence’s flourishing wool industry.

During Donatello's lifetime, the wool business employed no less than 30,000 workers, a third of the population of Florence, who annually produced 100,000 metres of textiles and clothing.

The buyers and exporters of wool and cloth was over time able to amass large fortunes, which they used to lend at interest to various European rulers. Most of these bankers were organized within a guild called Arte di Calimala. The strange name Calimala, Calm Her, came from the name of the street where Arte di Calimala’s headquarter was located. Through their wealth, members of this guild were able to influence and manipulate the rulers of Florence. Most influential among the members of this particular guild was the Medici family.

A picture in an Italian comic book illustrates the state of affairs in Donatello’s Florence. Donald Duck is toiling away shearing sheep and collecting wool while his Uncle Scrooge is counting the money he has received through wool sales and banking.

Like several other northern Italian trading cities, Florence was during Donatello’s lifetime governed by an assembly called the Signoria. Its nine members were chosen from the city’s leading guilds. Six of them came from guilds called Priori, i.e. the six ancient and most powerful guilds, among them the Arte della Lana and Arte di Calimala. Two additional members were elected from the fourteen ”minor” guilds. The ninth member of the Signoria was named Gonfaloniere di Giustizia and served as its chairman. He was elected every two months, not by lot but by members of the outgoing Signoria.

One of the several peculiarities of this form of government was how the members of the Signoria were elected and the short time they served as decision makers. The names of all guild members over the age of thirty were placed in eight leather bags. Every two months these sacks were carried out of the church of Santa Croce, where they were kept and during a short ceremony the names were drawn at random. Only men who were not in debt could be elected, moreover they would not have had a seat in the Signoria during the past year and they could not have any family ties to the men who had served during the previous term. Immediately after their election, the nine members of the Signoria were expected to take up residence in the Palazzo della Signoria, which facade was adorned with the coats of arms of the guilds. There they would stay for the two months that their mission lasted.

That's how it all worked in principle, but over time intrigues and manipulations confused the already complicated system and power effectively came to rest with the Gonfaloniere di Giustizia, an office that came to be dominated by the increasingly powerful Medici family. However, this did not mean that the guild system and its influence on Florence’s power game disappeared. For several centuries, the Signoria continued to dominate the economic and political life of the city.

The Arte della Lana, of which Donatello’s father was a member, controlled the entire process from the raw, packaged wool that on a daily basis arrived in the city, to the finished textiles produced at looms scattered among private homes and manufactures located within the city walls.

Like other guilds, the Arte della Lana coordinated and controlled the activities of its members; guaranteed the quality of the production, set prices, regulated wages, checked the training of journeymen, tested and decided who should be awarded a master craftsman's certificate.

Each guild had its patron saint, while its board resided in a palace, generally they also supported and paid for Catholic masses and the maintenance of a specific church. The mighty Arte della Lana resided in an impressive palace in the very centre of the city, its patron saint was St. Stephen and its church was none other than Florence’s Duomo – Santa Maria del Fiori.

In niches around the Chiesa di Orsanmichel, there are statues of the patron saints of the various guilds. Arte della Lana’s St. Stephen had been sculpted by Lorenzo Ghiberti, in whose renowned bottega Donatello at the age of seventeen had been accepted as an apprentice.

During Donatello’s lifetime the bottega system was well developed in Florence and the city counted on anumber of master bottegas. A bottega was more than an artist's studio, more than a place of learning for future masters and could best be described as a workshop that, under great competition, delivered commissioned work to various patrons. Much of the work was governed by strict routines marked by extremely important craftsmanship and tasks which depended on clients’ requirements, lack of time when it came to the execution of the complicated works, as well as the guild system’s production control and detailed regulations.

In particular, the maufacture of paints was an essential part of a bottega’s activities and for that reason Florentine painters belonged to one of the six most powerful guilds that made up the Priori – Arte dei Medici e Speziale, the Crafts Association of Doctors and Apothecaries, i.e. an association of specialists who made and used drugs and various decoctions. In addition to artists, the Arte dei Medici e Speziale also included shopkeepers who sold spices and textile dyes.

Each bottega produced its own colours. Paint production, as well as the careful preparation of canvases and specially treated wooden boards which constituted the base/groundwork for paintings, were labour-intensive processes handled by the bottega’s apprentices.

Colour pigments came from a variety of sources. They could consist of different types of soil containing minerals and clay, such as Raw or Burnt Sienna and Burnt Umbra. The pigments were often based on toxic substances such as mercury, lead, sulfide, tin, and cinnabar. They could also be constituted by very expensive imports such as Indian Yellow, which was made from the urine of cows fed on mango leaves, or most expensive of them all – the blue stone, lapiz lazuli, which was brought to Florence from Badakshan by the upper reaches of the river Amu Darya. To obtain the best pigments, artists were often forced to experiment on their own, or to gain such high esteem that patrons were willing to pay for their access to coveted and expensive pigments.

The pigments had to be grinded down to small, fine grains by using a runner, a cone-shaped stone with a flat bottom surface that was used to crush the pigments against a smoothened stone slab. When the pigments obtained the right grain size, they were compacted into a paste, by adding different binders. During Donatello’s time, the most common binder was egg yolk mixed with water – tempera. An alternative was to add oil, usually from linseed, to the solution, thus making it dry faster and permitting application to softer surfaces like canvas, instead of the commonly used base made of pine or poplar. Other common binders were beeswax and casein.

The artists’ workshops also produced various forms of varnish. The medieval name for varnish was the Latin word veronix, which gave rise to today's vernissage, the opening day of an art exhibition. During the Renaissance, this meant that when the varnish had dried the work of art could be considered completed and thus presented to the client. If the client rejected the result, it could mean a great loss of prestige for the bottega, as well as a serious financial setback.

Within a bottega, the hard-working apprentices were called garzoni, boys. Donatello’s entry as a garzone in the bottega of Master Lorenzo Ghiberti took place at an unusually old age. Generally, most garzoni accepted into a bottega were around ten years old. They were entrusted to their Master’s care. He nurtured, disciplined and taught them and they were considered to be part of his household. They lodged and ate together with their master’s family. Several garzoni did not advance from working with colours and panels, but the most skilled and enthusiastic of them were by the master taught to sketch, read and wtite, and could finally be allowed to participate in the completion of his works of art. Gradually, the most skilled garzoni were entrusted with more important tasks than the painting of decorative details and completion of the master's contours, or the colouring of previously delimited surfaces.

The guild required a master to provide his garzoni with an accartati, contract, and a fixed salary, the latter was usually quite modest—generally five or eight gold florins in a year, compared to a skilled labourer’s wages of about thirty-five florins within a year. At the end of his apprenticeship, a garzone could be offered to undergo a journeyman’s test. If he succeeded he was declared a journeyman and thus the opportunity to offer his services as an independent artist, though a journeyman was not allowed to establish his own bottega. That required membership in the Arte dei Medici e Speziale.

Guild members provided membership if a journeyman could present a Masterpiece (from which our contemporary word originates) that was accepted as such by selected guild members. If the jorneyman was accepted he was appointed Master of Arts and through a specific certificate he was thus granted the right to open a bottega of his own. First, however, a would-be Master had to prove he was the recognized son of a guild-member and willing to pay an entry fee, as well as signing a contract stipulating that he accepted the guild’s statutes and committed himself to submit an annual contribution to the guild’s common coffers.

The strict work discipline, fixed routines, the practical work that attached great importance to every single detail, the rigorous quality control of the guilds, fierce competition, the cooperation between a Master and his garzone, as well as the team spririt reigning within the guilds contributed to the fact that many Renaissance artists at an early age became exceptionally skilled craftsmen.

The earliest work of art that attributed to Donatello is a David he in 1409, at the age of twenty-three, carved in marble. The work had been paid for by Arte della Lana, the guild to which Donatello’s father belonged and it was intended to adorn one of the buttresses of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore. However, it was not placed there because the guild members thought it was too small to be appreciated from ground level. The statue thus remained for several years in a bottega before the Signoria in 1416 brought it to its palace and placed it on a pedestal with the inscription: “To those who bravely fight for the defence of the motherland, the gods provide help, even against the most terrible enemies.” Apparently, the city counsellors thought that the young, bold David could serve as a role model for defenders of the Republic.

Criticism has been harsh while judging this first known work by Donatello. It has been written that the dimensions are wrong, that the whole work gives a ”formal and bland expression.” This David of his has been mercilessly compared to Donatello’s later skills and declared to be quite uninteresting.

Having now seen it in real life, I arrived at a different opinion. Considering the circumstances that predisposed the manufacture of the statue, it is certainly a masterpiece. David rests his left hand by his side while he, positioned in an elegant contraposto, triumphantly lifts his long robe to reveal Goliath’s severed head, which rests at his feet – still with both sling and stone embedded in the skull. Despite the distance from which the sculpture would be viewed, the grotesque head is fashioned in great detail and prominently presented, with its closed eyes and half-open mouth, through which the dead giant’s tongue can be glimpsed. The killing stone has penetrated the forehead, the congealed blood is difficult to distinguish from clumps of tangled hair.

There is no doubt that the arrangement was intended to adorn a buttress and thus be viewed from below. It all seems to be striving upwards. The gesture of the left hand opening the garment makes the head of the defeated Goliath seem closer to us than the rest of the of the statue. It looks like the gory head has been placed in a cave formed by the robe. At the same time, the opening in the mantel is reminiscent of a flame striving upwards, making the entire sculpture, with its Gothically curved movement, remind us of earlier madonna-sculptures carved from ivory and thus being adapted to the curvature of the elephant’s tusk. Through their elegantly curved movements, these Virgins and their child seems to be lifted up towards heavenly heights.

David’s oversized right fist, which has often been criticized, and his relatively small, and not so empathetically characterized, head, underline the impression that the sculpture was to be viewed from below and from a great distance. Considering all this, I got the impression, particularly since the sculpted details cannot be discerned from afar, that Donatello’s David was in fact his “Masterpiece”, his entrance exam to a guild. Since Donatello at the time was active in Ghiberti’s workshop, which master was better known as a sculptor than a painter, it is possible that the guild which he entered as a recognized master was the Arte dei Maestri di Pietra e Legname, the Guild of Master Stonecutters and Wood Carvers.

Donatello's good friend and peer Nanni di Banco, who together with Donatello had been given the task of decorating Il Duomo’s buttresses, did seven years later make a famous sculpture group, which impressed his contemporaries and became a great inspiration for Donatello (who probably assisted di Banco with the manufacture) – Quattro Santo Coronati, Four Crowned Saints. These four martyrs, whose names were unknown, are by tradition said to have been Christian sculptors who under the Roman Emperor Diocletian refused to make sculptures of “pagan” gods and therefore were placed alive within sealed lead coffins and thrown into the Sava River in present-day Serbia. They had since then been invoked as patron saints of sculptors and were of course the obvious choice of the Arte dei Maestri di Pietra e Legname to adorn its niche on the church di Orsanmichele.

In 1405 Nanni had been appointed master of the aforementioned guild. The four figures are masterfully arranged within a shallow semi-circular niche, where, through glances and discreet movements, they seem to be involved in a conversation. The solemn gestures, the toga-like clothing and the volume of the bodies testify that Nanni was influenced by ancient Roman sculptural art.

Donatello’s marble statue of David had, during the exhibition at Palazzo Strozzi, been placed in the same room as another youthful work by Donatello – the Crucifix in Santa Croce. It hung next to Brunelleschi's crucifix from Santa Maria Novella. The reason for this was surely an anecdote in Giorgio Vasari's (1511-1574) anecdote in his Le vite de’ più eccelenti pittori, scultori e architettori, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects.

For Santa Croce, Donatello had “with infinite patience” carved a wooden crucifix, which he proudly displayed to his friend Brunelleschi, who, however, after Donatello’s enthusiastic descriptions, had expected something better and thus could not help to smile. The disappointed Donatello sensed his friend’s displeasure and asked him, in view of their great friendship, to tell him what he really thought of the crucifix. After some hesitation, Brunelleschi once again looked intensely at the crucifix and stated: “You have put a peasant on the cross and not Jesus Christ, the most perfect man ever born.” Bitterly, because he had after all expected praise, Donatello replied: “If it was as easy to make something as it is to criticise, my Christ would really look to you like Christ. So you get some wood yourself and try to make one yourself.”

Without a word, Brunelleschi nodded and left the church. Not revealing it to anyone, he set about making a crucifix with the aim of surpassing Donatello’s creation. After several months’ of hard work he produced, with great perfection, a work which, according to him, was superior to Donatello’s crucifix.

One morning Brunelleschi invited his friend Donatello to dine with him. Donatello naturally accepted the invitation and they walked together towards Filippo’s house. As they passed the market, Brunelleschi bought some ingredients for the dinner, and after stating he had a couple of more errands to run he gave the market goods to Donatello and asked him to take them to his bottega. When Donatello entered the workshop, he found Filippo’s crucifix stategically placed in perfect lighting. Overwhelmed with surprise and admiration, Donatello dropped the apron in which he had placed the eggs, the cheese and other items brought from the market. At the sam moment, Filippo arrive and found his friend standing among the broken eggs, lost in thoughts and apparently stunned by suprise. Laughingly, Brunelleschi asked: “What’s your design, Donatello? What are we going to eat now that you’ve broken everything?” “Myself,” Donatello answered, “I’ve had my share for this mornig. If you want yours, you take it. But no more, please. Your job is making Christs and mine making peasants.”

It is a quite subtle anecdote and Vasari’s anecdote has for posterity come to characterize differences between Brunelleschi’s and Donatello’s art. It has time after time been commented upon by various art critis.

The difference between the two representations of the dying Christ is actually not that great. It is clear that the two wood carvers found their inspiration in Giotto’s Triumphal Crucifix in Santa Maria Novella. Painted in 1288, it was more than a hundred years old when Donatello and Brunelleschi made their crucifixes.

Giotto was inspired by Franciscan spirituality, which more than paying hommage to his glory and sublimity, or inhuman suffering, had emphasized Jesus’ humanity, love and poverty. Giotto’s crucifix thus depicted a dying man, with a realistically rendered body. There are no signs of barbaric beatings or physical suffering. Christ wears no crown of thorns and the only wounds he exhibits are from the spear thrust into his side and the nails hammered through his hands and feet. Maybe he is already dead.