CARLO GESUALDO DA VENOSA: Murderous monster and musical genius?

Tags:

T.ex.: semester | bil | arbeteGerald looked at Halliday for some moments | watching the soft | rather degenerate face of the young man. Its very softness was an attraction; it was soft | warm | corrupt nature | into which one might plunge with gratification.

A pleasure of mine is to listen to CDs while I am alone in the car. Alone? Well, it means that I am able to listen with a concentration that cannot be achieved when the rest of the family is around, particularly since they are not so particularily fond of some of the sounds I occasionally like to listen to. I am not sure if it maybe called pleasurable, though it occasionally I find it quite fascinating to listen to music by composers like Schoenberg, Webern, Penderecki or Boulez.

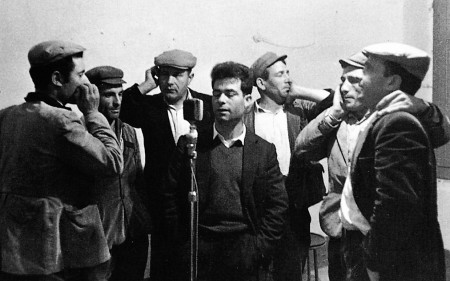

Lately I have taken every single drive as an opportunity to listen to madrigals, especially some of those written by Carlo Gesualdo da Venosa. Like most other madrigals these Gesualdo songs are generally sung without accompaniment, a capella (as in the church). The designation “madrigal” originates from Italian shepherd songs (mandra = cattle herd). Perhaps the original madrigals were somewhat similar to the apparently ancient, Sardinian cantu a tenore, which are sung in four voices (bassu, mesa bighe, contra and boghe) by at least four men, who usually place themselves in a circle. A few verses are sung by a lead singer who is answered by the three other men. The cantus are performed with a bleating, buzzing sound that may remind of the basso part that may be heard in some of Gesulado's madrigals.

When we several years ago visited Sardinia´s inland our hostess Vivi, who was a great Sardinian patriot, admirer of the island's Nobel Prize winner Grazia Deledda and Sardinian music, gave us a CD with the best cantu a tenore. Unfortunately, I have to admit that I rarely listen to it. The spinning, bleating sound is probably aimed at better connoisseurs than I. I assume I might be able to fully appreciate cantu a tenore after extensive studies, cantu a tenore is probably an acquired taste.

Obviously, time and dedication are also required to fully enjoy madrigals. Nevertheless, over time I have come to appreciate them more and more, maybe attracted by my interest for the idiosyncratic; things and behaviour that previously have been unknown to me, Views and opinions I initially have found to be quite odd and even incomprehensible. I am fascinated by naïve art, l´art brut and mannerism. Masterworks created by people who have been considered as “abnormal”, or even actively have refrained themselves to “be like all the others”.

Mannerism may be considered as a rebellion against Renaissance's lofty classicism, the worship of a fictional Antiquity, characterized by light and harmony. A view that several hundred years later was expressed in Winckelman's dictum eine edle Einfalt und stille Größe, so wohl in der Stellung als im Ausdruck, a noble simplicity and serene greatness in the pose as well as in the expression.

The Mannerists turned away from strict equilibrium and aesthetically chilly forms praised by the Renaissance. Or maybe rather ̶ they might also have been searching for some kind of perfection, though in another manner. A perfection based on personal expressiveness, a masterful utilization of the means at their disposal, both mental and technical, to create something entirely new, something astonishing.

Like the Florentine artist Giovanni Battista di Jacopo di Gasparre, commonly known as Rosso Fiorentino (1494-1540) mannerists were able to portray what they regarded as beauty, though by doing so they did not hesitate to distort what was considered sacred into something almost monstrous. This as part of their quest to realize their inner, elevated ambitions. Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), the great biographer of renaissance artists, was personally acquainted with Rosso Fiorentino, and stated that his art was characterized by a mixture of fierezza, wildness/pride and stravaganza, eccentricity, as well as Fiorentino´s and "contradictory idea". Vasari did not explain what he meant by the last statement, but from his descriptions of his admired friend it becomes clear that he considered Fiorentino to be a “fragmented”, distressed person who in his art was able to reveal strong passions through dazzling technical skills and exquisite aesthetics.

Through colour choices, body positions, shadows and strange gestures, Fiorentino imparted his motives with a bizarre originality that scared and dazzled his contemporaries. In an altarpiece like La Pala dello Spendalingo, Fiorentino enhanced the expressiveness of the saints surrounding the Madonna by accentuating their bodily peculiarities in such a manner that they distressed the spectators.

When the talented young artist showed his yet unfinished version of an altarpiece to a client, Leonardo Buonafede, spedalingo (director) for Santa Maria Nuova's Hospital in Florence, the wealthy benefactor became extremely disturbed, assuming that Fiorentino made fun of him. Terrified Buonafede exclaimed: "All these saints look like devils!" He was especially upset by the naturalist rendering of St Jerome´s aging abusiveness, which Fiorentino had based on studies he had made in the hospital's morgue. Nevertheless, Buonafede paid for the artwork to be completed, though he refused to place the finished altarpiece in the hospital's chapel, bestowing it upon an obscure parish church instead. After all, Buonafede was probably fascinated by the bizarre masterpiece.

In La Pala dello Spendalingo Fiorentino had wanted to express the depth and acuteness of his characters by emphasizing, among other things, the shadows around their eyes. Something that made the deep shadows above the eyes of Jesus appear as if he had four eyes instead of two. However, at closer inspection we may distinguish his blue eyes under the black shadows, though if we remove ourselves from the painting, the eyes and their shadows appear to be united in a creepy manner. This effect may be discerned by looking at a good reproduction, but if we find ourselves in the Uffizi Galleries, and if there are not too many people around, we may approach the painting and then back away until we find that the poor child stretches his hand towards us, while his eyes are transformed into two empty eye sockets, as if he was pleading to us from Aldilá, The Other Side. No wonder that Buonafede did not want to have such an altarpiece in his hospital chapel.

All of Rosso Fiorentino's works of art are distinctive; strange and engaging. I had often seen reproductions of his Descent from the Cross, exhibited at La Pinacoteca in Volterra, but a direct confrontation with it was overwhelming. Here it is the colour and the strict composition that amazes; unique for its time. Pastel-like clear and deliciously refined, the artwork transforms what should be a moving work of art saturated by sorrow and anxieties, into a subtle, exclusively aesthetic experience. Filled with motion and dynamism, but nevertheless cool, the Descent from the Cross gives an impression as if it had been frozen in time. Rose, I and Esmeralda became so absorbed by this artwork that we lost our concept of time and when we came out of the museum we found that we had been fined for excessive parking time.

Fiorentinos Pietá in the Louvre is quite different from his Descent from the Cross in Volterra. It was left in France after Fiorentino´s suicide, taking place while he was working as an appreciated master at the court of Francis I. The three Marias and St John are lamenting the death of Christ in what appears to be a cave. A cold light, maybe from the moon, shines upon a tightly closed group of people, filling the entire surface of the painting. The grey, pale corpse of Christ rests, strangely enough, on swelling velvet cushions. It is a claustrophobic, emotionally charged drama and this particular Pietá makes me associate with Gesualdo´s madrigals. These songs, which like the compressed movements within Fiorentino's work of art, tend to be acted out within a strictly limited format, generally based on between four to eight lines of poetry, though they are nevertheless interpreting a wide range of different states of mind, meandering back and forth.

Like Rosso Fiorentino, Gesualdo successfully mastered all techniques at his disposal and in an almost eerie manner he created innovative and haunting works of art. A prerequisite for the emergence of the art of the madrigal was the counterpoint technique, from Latin, punctus contra punctum, point against point. The art of merging voices that are harmonically interdependent, but yet different in rythm and contour. By Gesualdo we hear how melodies float next to each other at different levels and how their streams occasionally gradually are woven together at height or depth, within the so-called voice fabric, as well as temporally, meaning during the time the performance takes A master of madrigals strives to load each word sequence with emotional power, yes the music often provides every single word with a specific appearance, while voices are placed side by side, above or below each other, and/or are becoming intertwined.

Melody cords are braided through rising and falling halftones in such a manner that they come to suggest feelings evoked by the text and/or imply half hidden, double meanings. Impostare riso (risata) meant that the composer produced a quick sequence of tones to represent joy or laughter, while sospiro (sigh) meant that one tone descended towards another. Madrigal composers chose, or wrote, their lyrics in such a manner that the music came to serve not only as an illustration/accompaniment to the words, but became an integral part of an aesthetic totality, forming a total symbiosis. Madrigals were enabled to create exciting word landscapes where tones were turned into hues and brushes.

Luci serene e chiare

voi m´incendete, voi ma prova il core

nell´incendio, diletto, non dolore.

Dolci parole e care

voi me ferite, voi ma prova il petto,

non dolore, nella piaga, ma delitto.

O miracol d´amore!

Alma che è tutta foco e tutta sangue:

si strugge e non si duol, more e non langue.

Serene and limpid eyes

you inflame me, yet my heart

feels pleasure, not pain, amid the flames.

Dear, sweet words

you injure me, yet my breast

feels no pain, only pleasure, in its injury.

O, miracle of love!

A soul filled with flames and blood

is tortured without pain, dies without languishing.

Outbreaks burst through, becoming calmed by shades, harmonies are torn apart by abrupt contrasts, melodious are twisted, repetitions occur, all the while a quietly gyrating bass voice remains under a rapidly rising soprano, which remains high above advancing, underlying mutations, moving in swinging ripples. A constant commentary on, or association with, evocative words, until the voices unite, as in the madrigal above, in a jointly descent towards a gradually soothing coda, like blood slowly flowing into and becoming swallowed up by earth.

The madrigal's themes are typical of Gesualdo - love, longing and death. We find Christian rhetoric in the form of fire, blood and pain. The fire that burns and plagues, but does not consume, was a common picture of Hell's eternal torments. However, madrigals had nothing to do with the Church. They were a secular art form, unconstrained by piety and performed by small, intimate groups composed of both men and women.

We find us far away from today's mass consumption of music. All music was performed and interpreted within a local context. Peasants, shepherds and craftsmen sang and worked, danced and frolicked in search of friendship, entertainment and relaxation. Madrigals could be sung on streets and in squares, though most of them constituted an exclusive art form enjoyed within limited circles whose members could read music, play and sing and whose wealth attracted poets, composers and musicians who were refining the madrigals into something exclusive and sophisticated, distancing them ever more from their rustic origins.

In such closed camaraderie, where men and women were singing and feasting together, the intimate atmosphere favoured a veiled, yet pronounced eroticism. Madrigal singing's distinctive and insinuate word play, charged as it is with provoking sounds, has often been described as an erotically thrilling interaction between man and woman, where exclamations, dissonances, underlying bass and high sopranos have been suggested as resembling descriptions of sexual intercourse, where death, life, orgasm and mystery have merged.

The artistic, aristocratic jet set that was developed at the sophisticated d´Este court in Ferrara, during the greater part of the sixteenth century and during the first decades of the following era, became a vibrant centre for refined humanism. The artistic Count Alfonso II attracted an impressive circle of artists ̶ famous authors like Ludovico Ariosto, Battista Guarini, and Torquato Tasso; imaginative painters like Cosimo Tura, Lorenzo Costa and Dosso Dossi, as well as renowned musicians such as Josquin Desprez, Adrian Willaer and Cipriano de Rore.

Especially famous and admired at the time was Alfonso's trio constituted by virtuoso female singers ̶ Concerto di donne ̶ capable of adapting to and performing the most complex creations by demanding madrigal masters. The young Prince Carlo Gesualdo da Venosa, member of Campania's most powerful and influential family, was attracted to and welcomed in Ferrara. He was already a prominent virtuoso on Spanish guitar and archicembalo and had in spite of his young age already composed several innovative madrigals

Carlo Gesualdo was a serious young man, born into a refined and pious environment. Pope Pius IV was the uncle of Gesualdo´s mother. This may not say much about the piety of the Gesualdo clan, papal courts of the time were known to be sinister nests of sin and usury. Pius IV, or Giovanni Angelo de'Medici that was his original name, was for certain a quite typical Renaissance prince, who initiated his papacy by granting a general pardon to participants in riots and murders that had followed upon the death of his widely unpopular predecessor and immeadetly brought to trial several of the deceased pope´s corrupt nephews. One, Cardinal Carlo Carafa, was strangled, while another, Duke Giovanni Carafa and several of his relatives were beheaded, while others were given long prison sentences. Soon afterwards Pius IV embarked on a profound change of the crumbling Catholic Church, inspired by one of nephews, Cardinal Carlo Borromeo.

Carlo Borromeo was one of the most important motivators of the Catholic Counter Reform. He popularized the catholic mass by emphasizing the importance of well-performed and inspiring church music and instituted what could be regarded as precursors to present-day Sunday schools. Borromeo also introduced a strictly supervised discipline of the clergy, which among other measures meant that that corruption, sexual misconduct and concubinage, which had become common among the clergy, were severely punished and all priests were forced to undergo proper education. The Church´s practice and teaching had to be governed by a strictly applied catechism, Catechismus Romanus, which elaboration and implementation Borromeo controlled.

Borromeo lived modestly deprived of any kind of luxury and personally cared for the poor and sick, as well as he regularly presided over funerals for poor persons. During a deadly plague in Milan, he organized relief efforts meaning that more than 60,000 persons were receiving food and were provided with access to medical treatment, the deceased were buried without delay, while streets and squares were kept clean. Borromeo's motto was humilitas, humility, and shortly after his death he was declared as a saint.

Borromeo, was however not a tolerant person. When councils of several Swiss valleys guaranteed unrestricted freedom of religion and thus left the field open for protestant reformation, Borromeo personally intervened and did everything to wipe out "blasphemous opposition”. During a 1583 visitation to the Swiss valley of Mesoleina, Borromeo preached vigorously against Protestant “delusions”, ordering the Catholic clergy to unhesitatingly quench any tendency towards heresy. During his visit 150 persons were detained and severely punished for practising witchcraft. Eleven women were burned alive for the same crime.

Nevertheless, Carlo Borromeo was also a quiet, highly cultivated and attentive person. He died when Carlo Gesualdo was eighteen years old, but on several occasions he had met with his famous and widely admired uncle (who nevertheless survived a serious assassination attempt carried out by disgruntled priests) and all throughout his life Carlo Borromeo remained an important role model for Gesualdo, who directed his prayers to him, convinced that his uncle watched over him from his Heaven.

However, Carlo Gesualdo was not at all attracted by any church career. Music was his all-devouring interest and at the d'Este court in Ferrara he met with his time´s greatest madrigal masters ̶ Luzzasco Luzzaschi, Giaches de Wert and Lodovico Agostini. Especially Luzzaschi was furthermore known for being a skilled educator and he took Gesualdo under the shadow of his wings, while the young composer and archicembalo virtuoso often spoke with Duke Alfonso, who according to Gesualdo "constantly talked about music". The duke was fascinated by the serious youngster:

It is obvious that his art is infinite, but it is full of attitudes, and moves in an extraordinary way.

It is assumed that Gesualdo in his later madrigals went beyond the pretences of mannerism and deeper into his search for adequate expressions of his deep and personal pain. His most famous madrigal, Moro, lasso, al mio duolo, has been both loathed and admired. Like many other madrigals, it seems to depict both pain and death, as well as sexual bliss and it does so in a rather eerie manner. Gesualdo applies numerous cadances, inflections of the voices, modulations, declinations, dissonances, brief moments of silence and chromatic displacements. The soprano hovers, ripples, above it all while the tenor's underlying movements constantly increase the tension and stress of the madrigal.

Moro, lasso, al mio duolo.

e chi mi può dar vita,

ahi, che m'ancide e non vuol darmi aita!

O dolorosa sorte,

Chi dar vita i può, ahi, mi dà morte!

I die! Languishing, of grief

and the person who can give me life,

alas, kills me and does not want to give me aid.

O woeful fate!

That the one who can give me life, alas, gives med death!

Although Carlo Gesualdo, like other madrigal composers, collected his songs in books, various version of Moro, lasso, al mio duolo differ quite a lot from each other. Personally, I prefer the interpretation of the The Deller Consort, softer and more beautiful than most other renderings, which tend to emphasize the madrigal´s lugubrious character.

Moro, lasso, al mio duolo is undoubtedly both beautiful and somewhat scary. However, my musical knowledge and ability to completely sink into it are not so strong that I have been able discover what several musicologists have found. For example, Giancarlo Vesce: "In Gesualdo’s madrigals, I can tell that voices are suffering. Gesualdo is the highest expression of pain in music.” Susan McClary feels that Moro, lasso, al mio duolo provides an impression of how someone is “tied to some instrument of torture worked by means of a slowly turning crank.” The Australian composer Brett Dean writes that Gesualdo “creeps inside and grabs your soul and is in no hurry to let go.”

Several early music critics, who celebrated harmony, taste and beauty, tended to despise Gesualdo´s work, in particular Moro, lasso, al mio duolo. Great appreciation first came with composers like Wagner, Bruckner and Rickard Strauss. For example, did the influential music historian Charles Burney (1726 - 1814) disapprove of Gesualdo´s art, while he greatly appreciated several of his contemporary madrigal masters.

With respect to the excellencies which have been so liberally bestowed on this author they are all disputable, and such as, by a careful examination of his works, he seemed by no means entitled to. […] His original harmony, after scoring a great part of his madrigals is difficult to discover; and as to his modulation, it is so far from being the sweetest conceivable, that, to me, it seems forced, affected, and disgusting. His style [is] harsh, crude and licentious. […] not only repugnant to every rule of transition at present established, but extremely shocking and disgusting to the ear, to go from one chord to another in which there is no relation, real or imaginary: and which is composed of sounds wholly extraneous and foreign to and key. […] as it only consists of such licentious and offensive deviations from rule, as have been constantly rejected by the sense and intellect of great professors, it can only be applauded by ignorance, depravity, or affectation.

When Igor Stravinsky, in the early 1950s, became acquainted with Gesualdo's music, it took him by storm. It was during the last phase of his creativity, which commonly is divided into his Russian - (1907-1919), Neoclassical - (1920-1954) and Serial period (1954-1958), when Stravinsky became increasingly interested in Arnold Schoenberg´s twelve-tone technique and various forms of sacred music. He was caught by what he perceived as Gesualdo's bold expressionism. Stravinsky studied facsimile and originals of Gesualdo´s madrigals, copying and rearranging them. Twice Stravinsky visited the village of Gesualdo to wander about in the ruined castle where the composer had spent the last eighteen years of his tragic existence.

Together with his young student Robert Croft and musicologist Glenn Watkins, Stravinsky dwelt deeper and deeper into Renaissance music. Watkins was editing and tracking as much as possible of Gesualdo´s music and Stravinsky helped him by adding such voice parts that some madrigals and motets seemed to be missing. With increasing age Stravinsky had become more religiously inclined and assumed that he in Gesualdo´s later music found strong expressions of pain and guilt. The result was a passionate and personal somewhat idiosyncratic music , which nevertheless moved within a strictly classical frameworks, an appreciation that may be discerned in Stravinsky's Momentum pro Gesualdo, instrumental interpretations of Gesualdos madrigals that in 1960 accompanied a ballet choreographed and staged by George Balanchine to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Gesualdo's birth. Seven male and seven female, black and white dressed, dancers interpret the music in a strict, almost abstract manner, thus illustrating the balance and harmony of a music that often has been considered to be disharmonious and pretentious.

The interest in Gesualdo and his music is far from being an exclusive result of his music, an equal and even greater interest has been devoted to the man behind the work and this has often become a search for the answer to the question "Can exquisite art be created by a violent murderer, a depraved monster?" It is quite possible that Stravinsky's interest in Gesualdo was fired by the English writer Aldous Huxley.

Stravinsky had in 1939 fled from the outbreak of the World War II and found refuge in Hollywood where he around himself gathered a group of other brilliant refugees. Among them was Aldous Huxley, who with the admired Russian shared a taste for strong liquor, something that flowed during the two men´s notorious “Saturday lunches” when they spoke in French.

During his time in Hollywood (which, moreover, was quite successful since Huxley earned a lot of money from scriptwriting) Huxley, like Stravinsky, had become increasingly interested in religious mysticism, in Huxley's case of the Oriental brand. In addition, Huxley had begun experimenting with different mind altering drugs. It was during a violent mescaline induced rush that he had been deeply shaken by some of Gesualdo´s madrigals:

Through the uneven phrases of the madrigals, the music pursued its course, never sticking to the same key for two bars together. In Gesualdo, that fantastic character out of a Webster melodrama, psychological disintegration had exaggerated, had pushed to the extreme limit, a tendency inherent in modal as opposed to fully tonal music. The resulting works sounded as though they might have been written by the later Schoenberg.

Huxley was shocked, bewildered. Particularily by the fact that what could have been a disordered jumble turned into something completely different. According to Huxley, Gesauldo´s “Counter Reformation psychosis” had devoured the ordered Medieval polyphony, chewed it up and transformed it:

The whole is disorganized. But each individual fragment is in order, is a representative of a Higher Order. The Highest Order prevails even in the disintegration. The totality is present even in the broken pieces. More clearly present, perhaps, than in a completely coherent work. At least you aren’t lulled into a sense of false security by some merely human, merely fabricated order. […] But of course it´s dangerous, horribly dangerous. Suppose you couldn´t get back, out of the chaos …

.jpg)

Huxley eventually became a major introducer of Gesualdo´s music, including an appreciative text on an album cover for an LP with Gesualdo's madrigals that came out in 1957.

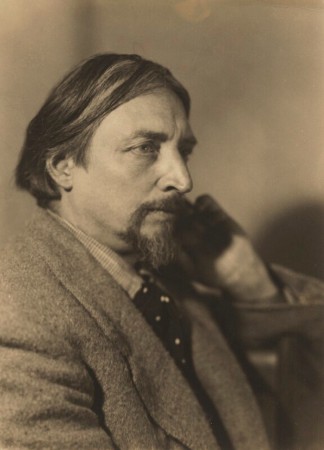

Huxley had maybe in his turn been introduced to Gesualdo by a remarkable character named Philip Heseltine, who generally introduced himself under the pseudonym of “Peter Warlock” (Witch Master). He makes an appearance in Huxley's novel Antic Hay from 1923. A novel that relates the conversations and activities (much drinking and fornication) among disheartened, cynical and intellectual snobs in London. Among them the posturing Coleman/Warlock, proud of his blond, Pan-shaped beard and bright blue eyes he behaves as if “his mind is full of some nameless and fantastic malice” and poses as a dedicated Anti-Christ:

”I believe in one devil, father quasi-almighty, Samael and his wife, the Woman of Whoredom. Ha, ha!” He laughed his ferocious, artificial laugh.

A few years earlier Warlock/Heseltine had appeared in D.H. Lawrence´s novel Women in Love from 1920, there in the guise of the overbearing upper-class brat Halliday. Squeamish and mannered he annoys his surroundings through his "high-pitched, hysterical" voice. Nevertheless, the obviously depraved Halliday exerts a great attraction on both men and women.

Gerald looked at Halliday for some moments, watching the soft, rather degenerate face of the young man. Its very softness was an attraction; it was soft, warm, corrupt nature, into which one might plunge with gratification.

.jpg)

However, Peter Warlock was a serious composer. Contemplative and beautiful his work is often based on folk melodies and renaissance music, such as the melodic Capirol Suite for String Orchestra, inspired by Renaissance dances and The Curlow with poems by W. B. Yeats. Warlock was also a diligent music writer, close friend of Frederick Delius, whose biography he wrote. He introduced Béla Bártok, whom he visited in Budapest, to English audiences and wrote lively and knowledgeable about European Renaissance music. It was this interest that brought him in close contact with Carlo Gesualdo, not only attracted by the master´s fascinating music, but his strange life story as well

Warlock identified himself with what he believed to be Gesualdo´s demonic nature. Attracted by occultism and black magic, Warlock was fascinated by people like the madman Aleister Crowley, self-proclaimed as “the wickedest man in the world”. Warlock eventually declared himself top be a convinced Satanist, paying homage to drunkenness and indulging himself in all kinds of perversions.

After retiring to the village of Eynsford in Kent, together with his good friend the composer Ernest Moeran, Warlock devoted himself to a daily intake of alcohol and drugs and with like-minded artists and friends he became involved in various sado-masochistic pastimes. It was in Eynsford he and Moeran researched and wrote a biography of Gesualdo, celebrating violence and depravation as a path towards artistic liberation.

Drug abuse and writer´s block soon broke down Warlock and thirty-six years old he killed himself in 1930 after writing an epitaph for his tombstone:

Here lies Warlock, the composer,

who lived next door to Munn, the grocer.

He died of drink and copulation,

a sad discredit to the nation.

It goes without saying that the self-destructive, perverted, occult-interested, satanist-inspired, bisexual and on top of that remarkable composer Peter Warlock would be interested in a another musician who has been characterized as:

A clearly mentally disturbed man, prone to rage and melancholy, and with strong sadomasochistic tendencies. I was these passionate excesses that gave his music its enduring qualities, but at the same time, he was living proof that great art cane be created by the vilest, most despicable and inadequate of men.

Novels, poems, movies, operas and even comic books have been devoted to the "demonic murderer" Carlo Gesualdo da Venosa, count of Conza and duke of Venosa.

An interesting work of art moving along the border line between reality and falsehood is a film by one of German movie´s most enigmatic film makers, Werner Herzog, creator of masterpieces like Aquirre and Kaspar Hauser, as well as incomprehensible failures like Queen of the Desert. In his strange quasi-documentaryTod für fünf Stimmen, Death for Five Voices, from 1995, Herzog blends serious interviews and scenes from authentic environments with invented stories. For example, when he is filming how a bagpipe player walks through Gesualdo´s castle ruin, to "drive out the evil spirits" with his music. Suddenly, a local, madwoman appears believing herself to be Carlo Gesualdo´s murdered wife Donna Maria d'Avalos. However, most Italians would at once recognize this alleged "madwoman" as the popular singer Milva, Maria Ilva Biolcati.

Likewise, the scenes of a retarded boy who for his therapy is taken to a riding lesson, are completely authentic, though the attending medical doctor's claim that he has two other patients who assume themselves to be Donna Maria is a lie. Herzog's visit to a decayed Neapolitan palace where the murder of Maria d'Avalos took place and his meeting with Donna Maria's descendant, the composer Francesco D'Avalos, who lived in the palace, is quite truthful. But, the bed he is shown as the place of the murder, is a fake.

What is then the reason for the fabrication of strange myths and legends connected with Carlo Gesualdo da Venosa? On the night of October 17, 1590, a palace in Naples became the scene of a gruesome double assassination, so brutal and insane that the locals may still talk about it. The event is preserved in a careful statement provided by Neapolitan authorities, who visited the crime scene the day after the event, interviewing the servants and later also Don Gesualdo who left had the city after his cime, but returned and immediately acknowledged the murder of his wife, the noble Maria d'Avalos, generally considered to be Naples' most beautiful woman, and her lover.

The male victim was Gesualdo´s landlord's stepson, the strapping Don Fabrizio Carafa, Duke of Andria, who due to his manly beauty was commonly known as The Archangel. The officials´ report established that they had found the duke's corpse lying on the floor, only dressed in "a woman’s nightdress with fringes at the bottom, with ruffs of black silk.” The body was covered with blood after having been pierced with many wounds. A gunshot that had gone straight through the elbow and his chest The head of the duke had been broken and “a bit of the brain had oozed out.” Head, face, neck, chest, stomach, kidneys, arms, hands and shoulders were pierced and underneath the corpse was a pattern of holes in the parquet “which seemed to have been made by swords which had passed through the body, penetrating deeply into the floor.”

Donna Maria d'Avalos, had had her throat slit and her nightgown was soaked with blood from several deep body wounds. Eyewitness interviews left no doubt about who had been the perpetrator ̶ the renowned Duke Gesualdo of Venosa, a twenty-five old who was considered to be one of Naple's most powerful men.

Maria d'Avalos, who was three years older than her husband, had already been married twice and both her former husbands had died. Her love affair with Don Fabrizio Carafa had been the talk of the town for more than two years and not the least Don Gesualdo himself was well informed about it. The drop that caused the beaker to flow over was when one of his uncles, Don Giulio Gesualdo, who himself had been sneaking around the beautiful Maria d'Avalos, but had been forfeited, told his nephew that by accepting his wife's scandalous behaviour he brought shame upon their entire family. In this context it might be remembered that Maria´s lover, Fabrizio Carafa, was member of the noble family that Geusaldo´s mother´s uncle, the pope Pope Pius IV had persecuted so mercilessly and the Carafas were no friends of the Gesualdos.

.jpg)

Finally, Don Gesualdo announced to his wife that he would spend a weekend hunting with his friends and servants. A servant, Bardotti, had in the presence of others, before Don Gesualdo left his residence, stated that: "But, it's not the hunting season." Don Gesualdo had then responded, "You do not know what kind of game I'm looking for." The Duke left by dusk and the palace´s gates were left unlocked. Just after midnight, Don Gesualdo returned, accompanied by three men armed with crossbows and muskets. Gesualdo screamed at the top of his voice: "Kill that scoundrel, along with this harlot! Shall a Gesualdo be made a cuckold?” They rushed into Donna d'Avalo's bedroom and surprised the loving couple in flagrante.

Shocked servants heard shouts and terrified screams and soon afterwards a bloody Don Gesualdo appeared in company of his henchmen. However, he turned in the doorway and returned to the bedroom with the words: "I do not believe they are dead." Don Gesualdo immediately appeared again, covered in blood and obviously confused holding a key, smeared in blood. He held it up, stating: "Here is the key I found on the chair." Don Gesualdo straightway left Naples for his castle in Gesualdo, where he awaited the representatives of Naples´s Real Giurisdiszione.

So far the official statement about Geusaldo´s crime. Myth and legends have added descriptions of how Gesualdo castrated Don Fabrizio and hacked into his wife´s genitals, how he ordered the battered bodies to be thrown into the street below and how Donna d'Avalo's body suffered further violations from an insane monk.

Despite all this insanity, Gesualdo was acquitted. Omicidio d'onore , honour killing, was not a crime under Neapolitan law and a few years later Carlo Gesualdo married Eleonora d'Este, niece of his friend Alfonso II of Ferrara. The time just after the gruesome killings became the most intense and productive period of Gesulado's madrigal composing, though his music now became pervaded by a strong sense of despair and anxiety. The marriage to Eleonora d'Este became unhappy. Their son died only five years old and the Countess often complained about her husband´s behaviour to her brother Alessando d'Este, who was Cardinal in Modena. Nevertheless, Eleonora d'Este did not divorce the unbalanced composer, but continued to alternate her time between Gesualdo's castle in his home village and Alessandro d'Este's court in Modena.

It has been said that Gesualdo's last years were characterized by unproductivity and an ever deepening melancholy. He mortified himself and let his servants whip him bloody. The last activity soon triggered rumours about homosexual depravities and unhinged sadomasochism.

At the outset, Don Gesualdo appears to have been exempted from guilt and shame for his bloody deed. However, public opinion gradually turned against him, perhaps mainly due to the composer's gloomy predisposition and a tendency to isolate himself, being obsessed by his own creativity.

After a couple of years, Gedualdo left Ferrara where he had established himself with his new wife and increasingly isolated himself in the village of Gesualdo. However, initially he visited Naples quite often, where he entertained friends and acquaintances from Ferrara, among them the famous poet Torquato Tasso. There is some preserved correspondence between Tasso and Gesualdo and the latter set several of Tasso´s poems to music. While the condemnation of Don Gesualdo's crimes became more intense and widespread even Tasso could not refrain himself from writing a poem about the bloody deed:

Piangete o Grazie, e voi piangete Amori,

feri trofei di morte, e fere spoglie

di bella coppia cui n’invidia e toglie,

e negre pompe e tenebrosi orrori.

Piangete Erato e Clio l’orribil caso

e sparga in flebil suono amaro pianto

in vece d’acque dolci o mai Parnaso.

Piangi Napoli mesta in bruno ammanto,

di beltà di virtù l’oscuro occaso

e in lutto l’armonia rivolga il canto.

Cry, thou Graces and you as well, Amor,

over Death´s mutilated victims, defiled remains

of a beautiful couple that jealousy carried off,

amid black pomp and gloomy horror.

Cry Erato and Clio over that ghastly act

and spread in lament your bitter tears,

instead of sweat water and Parnassian bliss.

Cry Naples, arrayed in brown,

over twilight´s victory over beauty´s virtue

and let the harmony of song vanquish grief.

Even if Gesualdo´s fame was even more tarnished over the years, he remained popular in the Campanian villages and small towns that formed the core of his shire; Gesualdo, Venosa, Conza and Avigliano, where you might still hear that the eighteen years he spent in Gesualdo were a prosperous time for the county. Each year, Don Gesualdo's memory is celebrated with various shows and concerts. A peculiar attraction is when a number of cultural associations agree upon presenting a live enactment of the altarpiece in Gesualdo's castle chapel.

The painting is called Il Perdono di Gesualdo, Gesualdo's Forgiveness, and by the time for the celebration of Gesualdo´s birthday a living replica of it is erected, consisting of a five-meter high and three-meter wide painted scenery within which living persons enact what is depicted in the painting. One reason for putting so much effort into staging Gesualdo's Forgiveness is a local conviction that Don Gesualdo's feeling of shame and guilt for the murders he committed were sincere and deeply felt.

The painting, which was completed in 1609, four years before Gesualdo's death, was painted by Giovanni Balducci, a Florentine artist, who for several years worked as court painter for the Gesualdo clan. It depicts how Don Gesualdo after his death by his uncle, the sanctified Carlo Borromeo, is presenting his nephew before the throne of Christ, where several saints have gathered - Mary Magdalene, foremost saint of penitence, Santa Caterina of Siena, patroness of fire and protectoress from all-encompassing passion, San Francisco, the humble saint, San Dominic, representative of science and Archangel Michael, the Devil's foremost adversary. At the bottom right we see Carlo Gesualdo's wife Eleonora d'Este and between the married couple, hovering above the flames of Purgatory, is their five-year-old son in the shape of an angel. Below him a suffering soul is delivered from Purgatory ̶ Don Gesualdo? At the same time a woman is also rescued from the roaring flames ̶ Donna Maria d'Avalos?

Does not such an altarpiece indicate a deep and sincere regret over committed crimes and sins? Several authors and locals have interpreted it in such a manner. Perhaps, Carlo Gesualdo da Venosa was after all not the sadistic monster that story and legends have made him into? Perhaps his later madrigals are honest expressions of great despair, regret and pain.

In the light of such insights, several musicologists have returned to the Neapolitan testimonies that were published after the gruesome murders and have then found some peculiarities. Everything seems to be far too well-ordered. Everyone knew that Maria d'Avalos was cheating on her husband and people wondered why it took him so long to act and seek revenge. In fact, according to Neapolitan law, it was justified for a husband to kill both his wife and her lover if they had been surprised in flagrante, yes ̶ not only that, it was expected that a honourable man got rid of an unfaithful wife and her lover; murder was anticipated, even demanded.

The gathered testimonies clearly indicated that Gesualdo before committing his bloody deed openly had declared that it was his intention to kill both wife and lover. The act was envisioned and well planned. Had Don Gesualdo not explained that he was going on a hunt and that "You do not know what game I'm looking for"? As he rushed into the palace, Gesulado had shouted what he intended to do. The detail that one of his victims, Fabrizio Carafa, was dressed in Gesulado´s wife's nightwear proved that Carafa had not passed by at a whim, something that was confirmed by the chambermaid who claimed that Maria d´Avalos "had the habit of asking me to put out the nightgown before Don Carafa arrived on his nightly visits." When Gesulado returned into the bedroom he had decaled:" They are not dead yet " and after remaining alone in there, supposedly delivering the fatal stabs, he absolved his henchmen from the actual assassination and furthermore brought back the key as a final proof that his wife had deliberately welcomed her lover. Don Gesualdo took upon himself the entire blame for the massacre.

It may happen that Gesualdo was a reluctant victim of the distorted morality of his own society. The fact that he during two years refused to act on the rumours of his wife's infidelity may actually be considered as an indication that Don Gesualdo was reluctant to harm his wife and when he finally did it in such an utterly brutal manner, it could be considered as a sign that he intended eliminate every suspicion of forbearance with his wife´s sinful and unscrupulous behaviour, a tolerance that would have brought shame on his entire family.

Without a doubt, Don Gesualdo was a great artist, and the despair he displayed in his later madrigals was maybe not at all a cunning device, but based on a deeply felt regret and shame. Carlo Gesualdo da Venosa was perhaps not the monster the story has made him into being, perhaps he was just a victim of his time. It was maybe not the gruesome murders, but the remorse he demonstrated, that made society turn its back on him, turning him into a despised outcast, the eternal representation of an egocentric, brutal, cynical and perverted artist. Possibly, he was a cruel and revengeful despot. Perhaps a love thirsting, confused, and sensible man with an artist's soul? A human being, equally enigmatic and multifaceted as his madrigals?

Burney, Charles (1957) A general history of music, from the earliest ages to the present period. New York: Dover Publications. Huxley, Aldous (1960) Antic Hay. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. Huxley, Aldous (1978) The Doors of Perception. Heaven and Hell. London: Panther Books/Granada. Lawrence, D. H. (2007) Women in Love. London: Penguin Classics. Longhini, Marco (2009) “Carlo Gesualdo da Venosa (1566-1613); The Fourth Book of Madrigals, 1595,” CD booklet: Carlo Gesuado da Venosa: Madrigals Book 4. Frankfurt: Naxos International. Manfredi, Franz (2013) “Il perdono di Gesualdo. Spacca pro loco e realizzatori” https://www.aviglianonline.eu/news_dettaglio.asp?idto=1577 Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2009) Monsters: History´s most evil Men and Women. London: Quercus. Ross, Alex (2011) “The Prince of Darkness” in The New Yorker, Dec. 19. Smith, Barry (1994) Peter Warlock: The Life of Philip Heseltine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Watkins, Glenn (2010) The Gesualdo Hex: Music, Myth and Memory. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.