FLU, MASQUES AND WITCHES

When I left Rome two weeks ago, I found that most of the airport personnel had been provided with surgical masks. Once inside the plane, I became drowsy. I don´t know why, but when a plane is about to take off I have an urge to go to sleep.

.jpg)

While closing my eyes before departure I imagined I saw Richard Prince's suggestive painting of a nurse wearing a surgical mask. It is a quite troubling work of art with its black background and dripping paint, reminding me of Francis Bacon's screaming popes, enclosed within their absurd power.

.jpg)

Her soiled medical makes Prince's nurse anonymous, almost intimidating, like a disguised criminal. The sinister mood is further emphasized by white lettering behind her - Hurricane Nurse, making her appear as even more disquieting by turning her into some kind of feminine, imminent natural force.

Why did Prince name her Hurricane Nuse? Richard Prince made himself a name by using commercial myths in his art, such as the so-called Marlboro Man a virile, cigarette smoking cowboy. I suspect Prince's Hurricane Nurse is a similar role model, a female equivalent to the super-macho Marlboro Man. A powerful and attractive professional woman.

.jpg)

It would not surprise me if Prince had been inspired by Peggy Gaddis (1895-1965) who for several years once a month wrote so-called nurse novels, including one called Hurricane Nurse. I am fascinated by pulp fiction writers. While writing my extensive blogs I identify myself with their hectic prolificacy, like Barbara Cartland with her record number more than 700 novels. Peggy Gaddis ”only,” wrote around fifty novels, though that was not a bad output either. I consider my blog-writing to be akin to Peggy Gaddi's description of her pencraft: ”It's a kind of drug, for which I hope no one ever finds a cure”

.jpg)

I haven't read anything by Peggy Gaddis, though I assume her nurse novels were far spicier than those Helen Wells (1910-1986) wrote about Cherry Ames's platonic relationships with various strapping and admirable Men in White. Helen Wells was even more productive than Peggy Gaddis, writing at least fifty novels under her own name and several others under pseudonyms. However, unlike Peggy Gaddis, Wells did not direct her novels to an adult audience but to girls, who in those days were not supposed to be exposed to an overly raw reality. Throughout her career, her heroine Cherry Ames was engaged in every conceivable professional role available to a nurse. Always remaining an impeccable role model; effective, beautiful and despite her romantic involvement with attractive, male superiors, she did in all novels remain single. Apart from doing her job, Helen Wells makes Cherry Ames solve several criminal cases. The author's obvious purpose was to stimulate girls to become professional, chaste and independent nurses.

.jpg)

My youngest sister, who I assume read the entire Cherry Ames series, actually became a nurse and I know she has enjoyed her career choice. I actually read some of the yellow-spined books about the super nurse (otherwise were girls´ books in those days generally red-spined, while boys´ books were green-spined). At that time, I was unrestrained in my reading and read almost anything I assumed was interesting among the books I found at home, and much more besides However, Cherry Ames proved to be a quite boring acquaintance. Too much romance and rectitude. And how could such a conscientious and skilled person like Cherry Ames change jobs all the time? The novels´ titles informed us that Cherry Ames had been army-, chief-, flight-, rest home-, summer camp-, rural-, private duty-, jungle-, department store-, boarding school-, dude ranch-, clinic-, and hotel nurse, apart from several other nursing jobs and on top of that she did not get any older. Was she constantly dismissed? I probably read two or three Cherry Ames books and then returned to Biggles and Deerfoot. These ”books for boys” were certainly not better written and far more prejudiced than those about Cherry Ames, but what was not at all noticed by a kid with an eye for adventure.

.jpg)

After vacillating between dream and alertness, I came round when the plane had reached its normal flight altitude. An internet connection was available and since no one was sitting beside me I had enough space för computer surfing – I don´t like using my cellphone for that.

I wanted to know more about the coronavirus and what I found was fascinating. The microscopic virus world is just as remarkable and incomprehensible as any other phenomenon in the Universe, by far exceeding the limiting framework of our human mind, enclosed as it is within questions like "how?" and why?".

It has been stated that a virus is not a life form because it lacks a metabolism of its own and is unable to reproduce without entering an organism. Nevertheless, it is alive in the sense that it is able to breed and can thus be described as ”an intermediate entity”, something in between living and dead matter. Viruses propagate by invading living cells, using their functions to create new virus particles.

As with living organisms, there are a variety of ”species”, or forms, of viruses of which at least six hundred ”survive” by infecting humans. Their existence is dependent on our misery, like humans viruses are parasites exploiting, damaging and often destroying other life forms. Virus causes a wide variety of phenomena, some are violently feared, others considered to be fairly harmless. However, all viral infections can have a lethal outcome and there is no cure for any of them, although some can be vaccinated against. Some examples of diseases causeb by viruses are herpes, shingles, brain inflammation, measles, mumps, rubella, polio, rabies, ebola, HIV/AIDS and influenza.

.jpg)

Every year, influenza viruses travel through the world and seriously infect between three and five million people, of whom between 290,000 and 650,000 dies. This is part of our human existence and rarely causes panic. However, fear spreads when ”new” viruses make their appearance. In 2002, SARS appeared in China and infected 8,098 persons worldwide, of whom 774 died. Less well-known is MERS, which in 2012 originated in the Middle East infecting 2,494 persons and killed 858. SARS probably spread from bats to civet cats and from them to humans, while dromedaries carried MERS.

.jpg)

The surgical masks worn at the Rome airport were designed to protect people from the Wuhan Corona Virus discovered in Wuhan on December 31, 2019, and traced to its markets. At the time of writing, we do not know for sure what animal it was that transmitted the virus to humans, though the main suspects come from the ”wildlife” markets. Something that, after my time in Hanoi by the beginning of the 1990s is not at all surprising to me. At that time, I could at the city's restaurants find a section which sometimes was written in French - de la forêt, ”from the forest” where dishes cooked on various exotic animals were offered. I and my good friend Svante Kilander, who at that time was Secretary of Embassy, often considered whether we should order a stewed pangolin. We jokingly wondered if you ate the animal's scales dipped in melted butter like the bracts of an artichoke. Thankfully, we never ate any pangolin, it would have given me a bad conscience.

.jpg)

Live and slaughtered dogs, pangolins, snakes, monkeys and other animals were sold at the large Dong Xuan market that burned down in 1994, a year after we had left Vietnam.

.jpg)

A few days ago I read that the pangolin is now the prime suspect for transmitting the Wuhan Corona Virus. One of the reasons for the spread of this specific virus may be that the hands of some pangolin butcher which after being in contact with the poor animal's flesh have transmitted the infection to people. The virus now spreads through direct skin contact, or by spreading virus particles through microscopic droplets that attack you if an infected person coughs you in the face. However, the virus cannot travel through the air at a longer distance than one metre.

As the name indicates, the Wuhan Corona Virus, like SARS and MERS, is a coronavirus. The denomination derives from the Latin word for ”crown” and comes from the fact that if the virus is viewed through an electron microscope it seems to be surrounded by a corona. like the sun. What looks like a shining corona is actually small ”tags” that link the virus to the cell that will be infected.

.jpg)

Like other unpleasant viruses, such as HIV / AIDS and ebola, coronavirus is a retrovirus. This means that the virus´s RNA molecule, which is single-stranded, i.e. it has only one chain, unlike the double-stranded DNA (double helix). The RNA strand of a coronavirus joins the DNA of an infected cell and this transforms it into another type of DNA. This abnormally altered DNA now affects the cell's information flow, which is stimulated to create harmful proteins. Under normal conditions it is the DNA that uses RNA as a ”messenger” between the genes, creating proteins that encode the hereditary information that is stored within each organism. The treacherous retrovirus uses its RNA to encode DNA, rather than the other way around, which is why it is called a retrovirus.

I an amateur when it comes to understanding and describing this strange microcosm, it might thus be that I have misunderstood the entire process, but that does not prevent me from being fascinated by how these strange transformations within a tiny microcosm can have enormous consequences in our human dimension of existence.

A common concern is that after a little more than a month, the Wuhan Corona Virus has proven to be more deadly than both SARS and MERS, it is already damaging China's economy. At the time of writing, on the twenty-first of February, 76 769 cases have been confirmed. In China, 2 239 persons have died from the virus, which now has spread to 26 other countries where it has so far only caused eight deaths.

.jpg)

All over the world people now fear that the Wuhan Corona Virus might develop into pandemic just like the deadliest flu epidemic ever – The Spanish Flu that agonized the entire world during the end of World War I and during some of the following years. In 1918, it killed my grandfather, made my father fatherless at the age of one year and forced him, his four siblings and my grandmother to live in poverty for many years. People were weakened by the war and other tribulations caused by it. Tightly-knit groups in trenches, in barracks, or during troop transports spread the virus at great speed, a development further supported by new, improved means of transport. Spain was not particularly hard hit, but since this nation did not participate in the war and furthermore had better health control than most other countries, the flu epidemic could be ascertained, tracked and means to control it was early put in place, hence the name Spanish Flu.

The pandemic raged at its worst between March 1918 and June 1920, reaching Inuit in the Arctic and Polynesians in the Pacific. Spanish Flu became the pandemic known to have killed most humans in shortest time. In twenty-five months, it killed between 50 and 100 million people, i.e. three to six percent of the world population. An estimated 500 million were infected, which corresponds to one-third of all people at the time. Of those diagnosed with the flu, at least 2.5 percent died, which can be compared to a normal flu epidemic during which no more than 0.1 percent die.

.jpg)

In contemporary photographs, we see that healthcare personnel just like now wore surgical masks. How effective are they really? WHO, The United Nations World Health Organization, notes that the use of surgical maks is no guarantee against infection. These masks, which are most common, were actually made to keep infectious agents from surgeons´ noses and mouths while operating and not designed to protect from virus particles. They can nevertheless provide some protection, but they do not seal of mouth and nose tightly enough and leave eyes and other parts of the body unprotected. In addition, after a day's use, the masks have to be washed, disinfected, or discarded. The Wuhan Virus also has certain properties making it difficult to control. Unlike SARS and Ebola, which are contagious only after symptoms of an infection have emerged, the Wuhan Virus may be dormant up to fourteen days and during this time a person, even if unaware of her/his sickness, can infect others not only by sneezing but through touch, speech, and even breath, though only within a radius of one metre. Even if our bare skin has been protected by gloves the infection might affect us if our gloved hands touch naked skin, for example of the face. Within an hour a person touches her/his face at an average of 23 times. More important than wearing a face mask is to wash/disinfect our hands as many times as possible and keep away from infected persons

Viral diseases are generally not curable. However, if they are dispersed within a large population their contagious abilities are thinned out while people´s immune systems are gradually strengthened. Nevertheless, the virus does not disappear entirely – it becomes endemic, i.e. restricted within a population group but not as lethal as it was at its appearance. This means that contacts with people who have not previously been exposed to a specific kind of virus might be lethally affected since they have not built up any sufficient immune defense against it. The result of such sudden infections can be devastating. Admittedly, The Black Death which in the mid-1400s, killed between thirty and eighty percent of Europe's population was not caused by a virus, but by a bacteria hosted by the Oriental Rat Flea, Xenopsylla cheopis, which fed on the Black Rat, Rattus rattus, but all indicate that the spread of the plague became devastating due to the advancing Mongolian army, which initially attacked the Chinese Yuan Empire during the 1330s when the Plague during three years decimated the population of the Hebei Province by ninety percent. Five million people died. The plague then spread throughout Asia. almost simultaneously with the advance of the Mongolian armed forces and the huge migrations they gave rise to. the plague reached Europe with Genoese galleys which arrived in Italy in 1347 from the port city of Kaffa on the Crimean Peninsula, which had been captured and looted by the Mongolian Golden Horde, Ulug Ulus.

.jpg)

Even more devastating than the Black Death were the pandemics that Europeans and Africans, together with cows, pigs and chickens, brought with them to America after 1492. Millions of people succumbed to viral diseases such as yellow fever, influenza, smallpox, chickenpox, and hepatitis. Most often the effect was syndemic, i.e. a number of diseases co-operated to infect and kill people, though it also happened that one disease could take the upper hand. For example, between 1545 and 1548, the bacterial disease salmonella killed eighty percent of Mexico's population, which had already been decimated by syndemic epidemics. Between 1575 and 1590, the salmonella returned to Mexico, killing half of those who had escaped its first attack.

During the 1700- and 1800s, smallpox killed 80 percent of the indigenous population in North America and between 1600 and 1650 malaria parasites, brought there by slaves from Africa, decimated large population in South America. What made the situation in the Americaz unique was that indigenous populations rarely recovered from the deadly epidemics. In Europe, economy and public health were generally boosted by ravages of deadly pandemics – the reduced labour supply made that farmers and workers generally were better treated than before the onslaught of plagues. The shock effect of mass death made people more likely to cooperate and make life more bearable for everyone. On the contrary, in the Americas indigenous peoples and imported slaves continued to be treated ruthlessly and their numbers were further decimated by deliberate extinction and inhuman oppression.

.jpg)

Afflictions, such as The Justinian Plague, which between 541 and 542 killed an estimated 25 to 50 million people, The Black Death with its 75 to 200 million victims and the so-called Third Pandemic, which in the mid-1900s killed at least twelve million in China and India were all a form of bubonic plague, caused by the plague bacteria Yersinia pestis, which like the flu, spread through sneezing, which made most people believe that the disease was carried by infected air, miasma. One way to protect yourself from bad air (mala aria) was to wear a mask in front of your nose and mouth, later on, combined with glasses. A feature of carnivals has often been masks inspired by those worn during plague epidemics, such as the Venetian mask called Il Dottore.

Plague, masks, and carnival have been portrayed by Edgar Allan Poe in his novel The Masque of the Red Death, in which Prince Prospero tries to escape a plague known as The Red Death. Together with friends and confidants he remains hidden away from the world in a monastery. One night the wealthy prince arranges a sumpteous masquerade ball in seven of the convent's halls. Each salon is decorated in a specific colour. During the festivities, a mysterious, ulcerous figure emerges. His face is hidden behind a hideous masque resembling someone who has been disfigured by the plague. The creepy character slowly moves back and forth from room to room, dampening the festive mood. Prospero becomes infuriated and cries out: ”Who dares insult us with this blasphemous mockery? Seize him and unmask him—that we may know whom we have to hang, at sunrise, from the battlements!” As no one in the festive crowd dares to raise a hand towards the eerie figure, who continues to slide from room to room, the enraged prince draws a dagger from his belt and rushes after the uninvited guest, who slowly has entered the azure room. The uninvited guest meets his attacker's maddened gaze, something that makes Propero fall to the floor, while his body is contorted by agonizing pain. After recovering from their shock, several of the masked guests throw themselves upon the frightening apparition, which now has reached the black room and looms next to a large clock, facing the hall. The men who try to seize the phantom find that they are merely grasping empty air.

And now was acknowledged the presence of the Red Death. He had come like a thief in the night. And one by one dropped the revelers in the blood-bedewed halls of their revel and died each in the despairing posture of his fall. And the life of the ebony clock went out with that of the last of the gay. And the flames of the tripods expired. And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.

.jpg)

Maquerades and artificial euphoria cannot cover up the relentless presence of Death. An insight that was strongly emphasized during the aftermath of The Black Death, when churches and palaces were decorated with representations of the Dance Macabre and Triumph of the Death. People were frightened, but tried to master death by playing with it, as in the Venetian Commedia dell'arte

performances from which the Dottore masque originated.

.jpg)

This classic masque is unmistakably reminiscent of the one seen on a famous Roman copper engraving from 1656. The attire and face masque were designed by the French king Louis XIII's physician, Charles de Lorme (1584-1678). This kind of protective clothing was soon used by plague doctors all over Europe.

.jpg)

The equipment was based on theories about infected air as a vector of the plague. Accordingly, you had to protect your entire body and especially the respiratory organs, from the harmful effects of penetrating mal aria, bad air. The long beak of the plague mask was filled with aromatic herbs intended to keep the odour of bad air away and at the same time cleanch it from the foulness that was revealed by stench. As a matter of fact, the full coverage could actually protect the wearer from virus-carrying air particles and pest-spreading vermin. It was not until 1894 it was established that the plague orignated from a flea and the same year is was dicovered that malaria was spread by a mosquito.

.jpg)

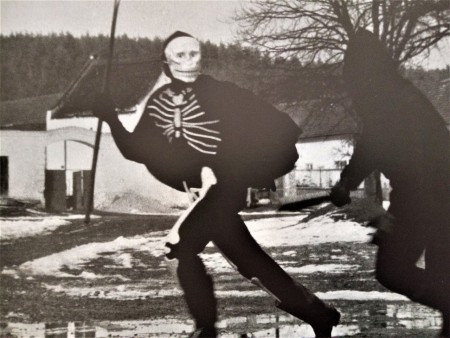

The grotesque appearance of the plague doctors soon became terrifying and tangible proof of the presence of death, and all over Europe they became part of masquerades, parades, and ceremonies reminding about ”the brevity of life, the certainty of death and the duration of eternity.”

.jpg)

Of course, illness, death, plague, and suffering were not only linked to the miasma, pestilent air, but that were also regarded as God's punishment for committed sins, incessant sloth and bad behaviour. In a similar fashion as unclean air had to be purified and kept out, people tried to free their communities from sinful influences; disobedient children, lazy people, strangers with unknown/abnormal behaviour and customs, in short – all deviations from ”normal behaviour”. Threats, fear and abuse were weapons used in healing and purification processes, while the sinister methods often were alleviated by jokes and a carnivalistic mood.

Filled with such thoughts, I got off the plane in Prague and took the train home to my oldest daughter's family. At night, when the others had gone to bed, my daughter and I talked about masques, horror and folk traditions. She suggested that we could visit the Prague Museum of Folk Culture and look at costumes and masks from rather terrifying Czech folk festivals. Janna had come to think about Czech Advent celebrations when villages and towns in the past, and in some places even now, were filled with people in frightening apparel. Not least so-called Barborcas who made their appearance on St. Barbora's day, the fourth of December. Could their attire be associated with both the Swedish St. Lucia celebrations and the Plague?

.jpg)

Women dressed in white robes, often armed with long knives as well as birch rods, walked from door to door not only during the Barbora day but often during evenings leading up to Christmas. Some of these Barborcas wore paper cones in front of their faces, others concealed them with veils and hanging hair. To ease their frightening looks, some also carried baskets filled with fruits and sweets that they gave away to the children.

When I told her about my thoughts about surgical- and plague masks, Janna showed me pictures of the ones worn by Barborkas and they undoubtedly reminded of plague doctors' masks. And really – as we checked the web for older depictions of Barborkas, we found that some of them actually carried masques even more reminiscent of the plague doctors´apparel. Where they really connected with the Plague? Maybe, maybe not – the Barborka outfit might just as well allude to birds, possibly storks, an impression supported by the fact that some Barborkas had bird claws instead of hands.

.jpg)

The stork and other aquatic animals often serve as fertility symbols and are in fairy tales connected with the birth of children. Such fertility associations might maybe explain why Barborkas carry baskets with fruits and vegetables? And why was it only women who dressed up as Barborkas? Why did they look and behave threateningly? Why did they carry birch rods and knives? Why were they dressed in white? Why did they show up during the weeks before Christmas? Furthermore, their costumes reminded of those being worn by masked penitents during impressive Easter processions in Spain and Italy, and not the least of Ku Klux Klan garments. Questions piled up and directed me towards exciting and somewhat worrying paths.

.jpg)

Birth and death, sorrow and joy. Loneliness and community. Starvation and illness. Seasonal changes, the unpredictability of nature. The familiar and the unknown. All this is present in our daily life and for sure overshadowed the life of peasants enclosed by daily toil and strong traditions.

Eventually, we visited Národopisné muzeum, Prague´s Ethnographic Museum and encountered a world characterized by a rich, beautiful, amusing, strange and sometimes macabre culture. Elegantly crafted work tools and everyday items, lavish wedding outfits, embroidered baptismal dresses, and blankets, all these exquisitely executed items testified that we humans are flock animals. We have a need to share both our misery and our happiness, something peasants occasionally did through great and impressive festivities. Many of these festivities were not exclusively focused on experiences of individuals but were collective events celebrating sowing and harvesting, winter and summer solstices, Pentecost, fasting, Easter, and Christmas.

Joint partying, shared joy, constituted an integrated part of a world where fertility and sterility, birth and death, were far greater realities than they are nowadays. It was common to regard black and white, life and death as opposite sides of the same coin, evident in traditions that have been maintained for centuries and thus convey an impression of being both time- and boundless. When we scrutinize such rites and conceptions we find layer upon layer of associations and ancient notions about how the world was created and how we should relate to it.

Extremely important times in the peasant calendar were winter and summer solstices. The word solstice is related to the Latin solstitium, combined by the word for ”sun” and sistere, ”to stand still”. People believed that during these times of the year the sun had paused at the northern or southern boundaries of its celestial path and then changed direction. Solstices constituted turning points in both human and nature's life. They constituted occasions for seriously reflecting on our existence, our moment on earth. This was especially crucial during the mid-winter solstice when the ground was frozen, the sky dark and starry and agricultural work resting. Accordingly, peasants were free to mull over the crimes and mistakes they have committed and realize that they probably hade to seize the opportunities that lie in store in an authentic reliance upon the grace of God or the gods. They also had to seek support from one another, in their shared ability to find and follow the path that leads to their own and thus the others´ benefit and salvation.

Such reflections and improvement were particularly crucial when the sun stood still and had been preceded by a time when evil forces had made themselves noticeable. A time of darkness, sterility, foul game and death that required the mobilization of benevolent forces to vanquish the evil powers and secure their dominion of Earth and the souls of men. Evil must be punished and driven away, a struggle that humans could contribute to by visualizing both the evil and the good forces.

It was now that Lucia processions made their appearance in Sweden and Baborkas roamed the roads and paths in Bohemia, the ancient name of the Czech Republic. Did those rites and processions originate from the Christian faith? Do they really honour saints like Saint Lucia and Saint Barbara? Probably not, they are rather manifestations, reverberations of ancient pre-Christain beliefs and rituals.

Canon Episcopi constituted a part of the medieval canonical law and was probably written sometime during the 10th century. Around 1140, the so-called Decretum Gratiani was adopted by the Pope and became an essential component of Catholic dogma. This decree was dispersed among the clergy and intended to serve as a weapon against everything that threatened the power of the Church. A guide not only in how to punish rebellions against the true doctrines of the Church but also devising methods of direct offenders to the righteous path through penitence and improvement and if that was not possible – punish or exclude them.

The bishops and their ministers should by all means make great a effort so that they may thoroughly eradicate the pernicious art of divination and magic, invented by the devil, from their parishes, and if they find any man or woman adhering to such a crime, they should eject them, turpidly dishonoured, from their parishes.

It is by Burchard (950 - 1025), Bishop of Worms, that we for the first time find written hints of a powerful and obviously international cult of a female, ”pagan” divinity. Burchard wrote comments on the text that would later be affirmed as Canon Episcopi. Several versions of this law eventually included Burchard's observations as part of the law text.

Have you believed there is some female, whom the stupid vulgar call Holda, who is able to do a certain thing, such that those deceived by the devil affirm themselves by necessity and by command to be required to do, that is, with a crowd of demons transformed into the likeness of women, on fixed nights to be required to ride upon certain beasts, and to themselves be numbered in their company? If you have performed participation in this unbelief, you are required to do penance for one year on designated fast-days.

.jpg)

Belief in an almost omnipotent female divinity, mistress of nature; fertility, birth, and death, appears to have been an essential part of traditional, European thinking, perhaps it was even a global phenomenon. Like nature, this divinity was beyond good and evil. In fact, she included in her character what we perceive as distinct qualities, like life and death. This mother-goddess of could reveal herself in both terrifying and benevolent manifestations. More than five hundred years after Bishop Burchard wrote his comments, Martin Luther mentioned Frau Hulde in one of his comments on the Bible's epistles. He appears to be describing a procession of disguised participants:

Here cometh up Dame Hulde with the snout, to wit, nature, and goeth about to gainstay her God and give him the lie, hangeth her old ragfair about her, the straw-harness; then falls to work and scrapes it featly on her fiddle.

.jpg)

In present-day Germany, stories might still be told about Frau Holle, an old lady who sneaks around during the night, visiting dreams of lazy girls, who may suddenly wake up by finding themselves lying naked in the street. Diligent little girls, however, may be rewarded with a silver coin under their pillow, or during bygone times with a coin falling into their buckets when they had been fetching water. Frau Holle has to do with water and in the depths of springs, wells, and lakes there is a path leading to a wonderful garden where she, as a white-clad old lady, receives both kind and naughty girls, whom she then rewards or punishes according to their merits.

The Grimm brothers told a story about her. A widow had two daughters, her own daughter whom she, as in most stories, spoiled and one stepdaughter whom she treated poorly. The stepdaughter was forced to sit next to a well, spinning day after day, though she was one evening stuck by the needle of the spinning wheel. However, when she went over to the well to rinse the needle and her bloody fingers, she fell into it. Instead of drowning, she found herself in a flowering meadow. As she walked across it, she came to a cottage surrounded by a blossoming garden. where she was greeted by a gentle, old lady who took her into her service. The girl watered the garden flowers, washed, aired and shook the bedding. When the girl once told the kind, old lady, that she despite in spite of all her graciousness longed for home, the benevolent Frau Holle let the girl return to her stepmother dressed in beautiful clothes and equipped with plenty of gold coins. When the stepmother understood what had happened, she threw her adored but miserably spoiled daughter into the well. This lazy and corrupted girl also ended up with Frau Holle, but misbehaved in such a manner that the powerful Frau made her return covered by filth and tar.

The story is one variant of many others that tell about omnipotent women disguised as nice old ladies, or nasty hags, testing the heroine's kindness and skills and abundantly reward her if she passes the ordeals. Frau Hulda is in Grimm's story welcoming and friendly, though for example in a folk tale retold by Alexander Afanasiev – Vasilisa the Beautiful, Frau Holle's Russian equivalent, the terrible old hag Baba Yaga, nevertheless rewards the steadfast Vasilisa just as generously as Frau Holle. The Grimm brothers' fairy tales also have their frightening witches, no less terrifying than Baba Yaga, for example in their tale about Frau Trude.

A defiant girl ignores her parents' advice to avoid visiting Frau Trude's cottage in the depths of the forest. The stubborn girl imagines her parents' prohibition is based on their superstitions and fears. However, she knows that the old hag is filthy rich and assumes she may be able to lure her off some of these riches. Frau Trude receives the girl in a courteous manner and asks her if she has met someone on her way to her secluded abode. The girl tells the truth – she has met but not spoken to a black rider, a ”charcoal burner” explains Trude, a green rider, a ”hunter” states Trude and finally a red rider, a ”butcher” according to Frau Trude.

Similar riders appear in the tale about Vasilisa the Beautiful and there they are the servants of Baba Yaga. A white rider, who is the Day, a red one who is the Sun and a black rider who is the Night. In Grimms´ tale the girl adds that she has also seen another creature. When she peeked in through the window of Frau Trude's cottage, she saw the Devil sitting there. The annoyed Frau Trude declares that she is really Satan himself and then transforms the girl into a log of wood, which she throws into the fire. The witch states: ”It heats well and the cottage has become brighter,” thus the story ends on a more infelicitous note that use to be the case of most fairy tales.

Child robbers, night walkers, cannibals and a host of other monsters haunt European fairy tales in all conceivable shapes and sizes. Ancient mythologies used to be dominated by female monsters but over time, male villains increased in number and prominence. Similarly, male tellers of fairy tales and myths gradually usurped a female story telling tradition firmly rooted in an ancient peasant society where men worked in fields and forests, while women were responsible for children and home. They spun, weaved, managed the gardens, baked and cooked. Their activities were related to fertility and maintenance, nourishing activities like raising children, being responsible for the sick and the old and thus they also preserved ancient traditions linked to female existence, women´s duties to care for life and prepare the dead for the afterlife. This, in any case, claims Marina Warner in her well-written and fascinating studies of popular storytelling – From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers and No Go the Bogeyman: Scaring, Lulling and Making Mock.

Manyof the stories told by these peasant women were about dangerous and ambivalent old hags, some of which might have preserved traits from ancient, pagan godessess, Frau Holle and above all the Russian Baba Yaga might indicate such origins. The Slavic Baba Yaga, who had a certain appetite for children's flesh, eventually evolved into an individual character, with a cottage moving on chicken legs and her unusual mode of flight. She traveled in a wooden mortar which she steered with a pestle while sweeping away the tracks left behind with a broom. She has had clattering teeth as a lock for her door, the roof was made of pancakes and the walls of meat pies. Baba Yaga was a multi-faceted creature, not only incarnate evil but also a cunning lady who ruled over sun and wind, over the seasons, life and death. Like many other fairy tale creatures, she was a shapeshifter and could assume the aspects of a cat or a bird. Forest birds were her servants, as well as several powerful men and gods, such as the three horsemen and the sinister Koščéj the Immortal, ruler of the Kingdom of Death.

One of the Grimm brothers, Jacob (1785-1863), was among the first to discern a close connection between fairy tales and traditions, rites and notions stretching far back in time, across borders and cultures. In his Deutsche Myhologie he extended descriptions of mythology from mainly having been devoted to written tales about gods and heroes, as well as records of established religious dogmas. Jacob's and his brother's studies of oral traditions made him compare them with contemporary customs and rituals, as well as written descriptions of historical customs and notions. All in an effort to trace the origins and development of ”Germanic” culture. Of course, he was often mistaken, particularly when it came to etymology, changes over time and specific cultural contexts. Nevertheless, Jacob Grimm's approach influenced later interpretations of different customs and was an important contribution to the budding science of ethnology. The concept had been established by Adam Franz Kollár´s epochal Amenities of the History and Constitutional Law of the Kingdom of Hungary published two years before the birth of Jacob Grimm. In this book, Kollár described ethnology as:

the science of nations and peoples, or, that study of learned men in which they inquire into the origins, languages, customs, and institutions of various nations, and finally into the fatherland and ancient seats, in order to be able better to judge the nations and peoples in their own times.

Before I return to Czech Advent customs let me follow some thoughts originating from Jacob Grimm's theories about the nature and origin of Frau Holle. He considered tales spun around her as evidence of the survival of an ancient belief in a nature deity, which had mingled with the Roman Diana and later on with Virgin Mary, Jesus's mother and Keeper of the World.

.jpg)

Jacob Grimm relates the name ”Holle”, with notions about Norse huldror, who were chotonic creatures. It appeared as if Frau Holle had inherited some eerie features from the huldror, for example in her role as mistress of the souls of the dead. Frau Holle's kingdom was placed under water and resembled some a kind of Paradise, like the medieval Virgin Mary's Rose Garden. Like some Catholic saints and angels, Holle presided over changes in the weather, which is crucial for any peasant. When the girl in the fairy tale waters the flowers of Frau Holle's garden it rains on Earth and when she shakes bolsters and pillows it snows.

Frau Holle is linked to ”female” chores, such as spinning and weaving, just like the ancient Nordic norns who spun the fate of humans. In the tale about the evil Frau Trude, probably akin to Frau Holle, the witch rules over three riders, who may be identical to the horsemen in the stories dealing with Baba Yaga, where they correspond to the sun and the circadian rhythm.

Furthermore, Frau Holle is a shapeshifter and manifests herself as both an evil and a benevolent creature, as light or dark, old or young. She is the epitome of a constantly changing nature beyond good and evil.

If we study ancient Slavic beliefs we may find that they are ambiguous, even bipolar. Chronica Sclavorum, which recounted the pre-Christian culture of Polabian Slavs, was written by the end of the twelfth century and suggested that Svetovid, their supreme god, had two aspects who in their own right were worshipped as gods, Belobog, the White God, and Chernobog, the Black God. This aspect of Slav religion is irrefutably proven, though it reflects quite convincingly much of the duality found among the creatures which emerge during Czech Advent celebrations. Not the least do Saint Barbora unite the evil and benevolent features of a being like Frau Holle and perhaps even more so in her threatening appearance as Frau Perchta.

The word perchta which later came to be associated with Saint Bertha/Barbora, or more correctly Saint Barbara, comes from the Old High German word perhat, "shining" or "brightness". Something that may be related to Frau Perchta's appearance by the beginning of December, an indication of the return of light after the winter solstice. In processions, Frau Perchta may just like Frau Holle appear crowned by a wreath with burning candles and it may be difficult to find any difference between these white-clad ladies and the famous Lucia, who at the same time is celebrated all over Sweden. Like Lucia do Perchta and Holle in their beautiful aspects wear wide, red silk ribbons around their waists.

.jpg)

However, it is more common to associate Frau Perchta not with brightness, but with paleness. White was until the middle of the nineteenth century the colour of death. A corpse turns pale; becomes grey or white. Both children and adults were buried in white clothes and usually in white coffins.

Frau Perchta lived at the bottom of wells from where she often attracted children whom she drowned. Like Frau Holle, Frau Perchta was often called The Dark Grandmother or The White Lady. When she emerges during Advent, it is mainly in the guise of a punishing lady with an entourage of evil and horrendous creatures, like the terrifying Krampus and/or children she has killed.

.jpg)

As mentioned above, Martin Luther described ”Dame Hulde” as girded with a corset of straw, probably a sign of her role as a fertility goddess. Straw and fertility are also connected with Frau Perchta/Barbora. She carries with her a basket of fruits and sweets to give to young women who diligently had spun hugh quantities of yarn and to children who had behaved well. However, the punishement she meted for sloth and misbehaviour was terrible, to say the least. With her sharpened knife she slit open the bellies of her victims, ripped out their guts and replaced them with straw.

In her Czech aspect as Barbora, Frau Perchta might also appear as a ghoul with her face hidden behind long, striped hair, she is then associated with a demon who sneaks into nurseries to kill, or even eat, babies. Child mortality used to be a dreaded and ordinary scourge and was generally blamed on supernatural forces.

.jpg)

Saint Barbora did not only manifest herself as the dreadful Frau Perchta, more common was that Barborkas represented her by placing long cones in front of their faces and some covered one of their feet with a dummy in the form of a bird's claw or goose's foot, emphasizing Barborka's quality as a water creature. Water is condider as the ultimate source of all fertility and as mentioned above aquatic animals such as frogs and storks were associated with childbirth.

Already during the Middle Ages, Frau Hulda´s entourage was labeled as ”demons”. Perhaps a remnant of the wild hunts that Odin and all kinds of beasts used to devote themselves to during the winter months when the powers of darkness were evoked from their hiding places and threatened to take over the world if they could not be kept in check by the mighty Nature Goddess. Nevertheless, evil creatures could be allowed to punish children and adults who violated social rules. Thus, even such a terrifying figure as Krampus could be considered as a servant of benevolent forces. He is an unusually disgusting, horned monster, described as "half goat, half demon" but even significantly more horrible than that. His name is derived from the Old High German word krampen which meant ether "claw," or "curved," a hint of his predatory appearance and behaviour and the fact that he is a grotesque abnormality, a mix of demon and animal. Possibly Krampus is akin to the Baba Yaga´s subordinate Koščéj the Immortal, a symbol of uncontrolled natural forces and the certainty of death.

.jpg)

In the Czech Republic, Krampus emerges as a companion to Saint Nicholas while he hands out Christmas presents to children. Krampus is then often called Čert, a name usually translated as The Devil. However, Čert is actually not the same creature as The Devil. He is certainly a demon, but the word apparently comes from čersti/čьrtǫ, meaning "to draw a line", "making a furrow" and Čert could then be considered to be an incarnation of Death and thus a servant to Barbora /Frau Perchta and their connections to birth and death.

.jpg)

Perhaps the Swedish Christmas Goat is a remnant of the horned Krampus/Čert. Before the Tomte, the Swedish equivalent to Santa Claus, took upon himself that task it was The Christmas Goat that came to Swedish children with both gifts and punishment. Another coincidence between the Swedish Christmas Goat and Czech Advent creatures may be the importance of the straw. The Swedish Christmas goat's mask was often made of straw and,like Krampus/Čert, he was generally dressed in a black fur coat. Even if the Chistmas Goat does not appear in person anymore, almost every Swedish home has a goat made of straw standing by the Christmas tree.

.jpg)

.jpg)

In Finland, the Christmas Goat, Joulupukki, has become Santa Klaus´s companion and may thus recall the chained Čert, who follows Saint Nicholas during his Christmas visits. The fact that Saint Nicholas has a goat- or devil-like companion is a common feature of several European Christmas traditions, although in Slavic folklore this companion is not always demonic, but exhibits the same ambiguous characteristics as those of exposed by Belobog and Chernobog.

In Russian folk culture, Saint Nicholas is often replaced by Ded Moroz, Father Frost, who is brought forward as white-bearded and cloak-clad, although his mantle is blue, or ice-coloured. The origin of Ded Moroz is probably a Slavic winter god, or "winter demon" as Christian missionaries would denominate him.

.jpg)

Ded Moroz's companion is not a devil-like creature but the beautiful Snegurochka, the Snow Maiden. She seems to be a Baba Yaga in her beautiful appearance, since like Ded Moroz Snegurochka is endowed with a double character. She can be both benevolent and wicked. When Ded Moroz does not come with gifts, he may appear as the Siberian winter cold, freezing his victims to death. In a similar manner, the cold Snegurochka can appear as the Mistress of Winter and thus also kill people through her iciness. Then she is called The Snow Queen and has as such inspired H.C. Andersen's fairy tale of the same name, which later palyed some part as an antecedent for the Disney Company's successful movie Frozen.

.jpg)

In German tradition, on the other hand, a vicious figure appears as Saint Nicholas's companion, but he is then more humanized than the animalistic beast Čert. Knecht Rupert is wearing a black or brown mantel with a wide belt. He is limping due to some childhood injury. The legend tells us that he was an orphan who Saint Nicholas took care of and later turned into a loyal vassal.

Knecht Rupert wears a pointed hood and holds a birch rod with which he punishes nasty children. He may also hit them with a sack filled with ashes, often adorned with bells. If he carries such a sack, he is called Belsnickel. The sack can also be empty and he then uses it to carry nasty children, down to a lake where he drowns them.

.jpg)

In this apparition, Knecht Rupert reminds me, as a child of the Swedish district of Göinge, of a song by Peps Persson, the great singer/poet of my native place, telling how an old Granny tries to frighten her grandchildren with a ghoul familiar from my childhood:

In the attic, she says, there lives a man with a beard down to his knees,

she says she has seen him from time to time, when she´s alone.

If the children ventures up there and if they are not nice,

he takes them and puts them in his child cage.

The kids laugh at her and say they don´t believe in such goofy stuff and that Santa Claus is a lie as well. They think it is a waste of time to listen to fairy tales and prefer to play with their video games instead.

In northern France, Sant Nikolaus has a companion who dressed like Knecht Rupert, but there he is called Père Fouettard, Father Scourger, and believed to have been a medieval innkeeper and butcher who served his guests with kids he had personally butchered and prepared.

.jpg)

However, the traits of these horrific creatures have mellowed over time and their sacks nowadays generally contain sweets and presents. They are in the Czech Republic matched not only by Čert, but also by one of Barbora´s/Perchta's companions. On the seventh of December, on St. Ambrose's day, a man appears dressed in a long, white shirt and a black pointed hat. With a veil in front of his face, a paper-covered broom in one hand and a candy bag in the other, he chases children around churches while "dropping" sweets on the ground. If someone dares to pick up the sweets s/he receives a blow with the broom.

.jpg)

Sankt Ambrose's equipment is reminiscent of the vestments penitents, apostates and heretics were forced to be dressed in before they were executed during the notorious autos-da-fé staged by the Spanish Inquisition. On their white, long shirts pictures had painted depicting punishments these sinners would suffer in Hell. The pointed hats seemed to imply they were penitents visibly suffering for their sins.

.jpg)

Similar hats are still worn by masked penitents who partake in Easter processions in Spanish and Italian towns and cities. It is no coincidence that they are reminiscent of the Ku Klux Klan's attire, this insane organization was established to terrorize blacks, Jews and Catholics. The clan members' equipment was clearly intended to, among other things, mock Catholic customs.

What fascinated me most about St. Ambrose's attire was that it made me think of St. Lucia's followers during the processions that are staged in every school and town in Sweden. This luminous personage with her white-clad bridesmaids and male companions with long pointed hats seem to have a connection with similar, continental processions, this while several peculiarities like the Lusse Cat Buns distributed by her and the candle wreath worn by Lucia remind of the Norse fertility goddess Freyja, who was connected with light and had the cat as her sacred animal. However, who are these Star Boys with their pointed hats? It is has been said that the hats indicate the three Magi, coming ”from the East” to worship the ”king of the Jews” (Matthew 2:1-12). It is very possible, but after being immersed in all these myths about the midwinter creatures I wished to learn something more about pointed hats as well, particularily since they appear to have several ancient connections to magic and power.

.JPG)

When, during my return trip from Prague, I made a few days stopover in Berlin to visit my youngest daughter, we made frequent museum visits. Among other things, we visited the collections at the Museum Insel. There I was confronted with depictions of pointed hats from differnt times and cultures. Most impressive of them all is a 75 cms high pointed hat crafted in gold sometime between 1000 and 800 years BC. It is one of three found in different sites in Germany, while another was found outside of Poitiers in France. Everything indicates that such artifacts have been common in other places as well. Apart from those gold hats, which obviously were too heavy and cumbersome to be worn as headgear, bronze-age gods and princes were obviously wearing pointed hats. It has been speculated that the striking gold hats, with their sophisticated symbols and patterns, may have had something to do with solstices.

.jpg)

It is quite possible that this may have been the case, however, one thing is certain and that is that such hats have been and still are of great importance in the most diverse cultures. Like a masque, a hat may change, cover and make a person visible. Among other things, I think of the expression that in recent years has become increasingly annoying during all kinds of official meetings: "Today I wear a different hat and represent ...". As soon as I hear that silly expression, it gives me the willies, just like the equally ridiculous saying "think outside of the box", generally uttered by people who do not do that.

A hat often represents something magical, something greater than the individual who wears it. If someone puts on Che Guevara's beret, Sandino´s or Bhagat Singh's hats, Arafat's keffiyeh, the French revolutionaries Phrygian Cap hat or feminists´ Pussy Hat, they make a statement, while the headgear transforms the bearer into something beyond her/his everyday existence. Similarly, when an English judge pronounced a death sentence he transformed himself into a higher, impersonal authority by putting on a black cap.

.jpg)

The typical symbol of a hat's magical, transformative qualities is otherwise the pointed hat of magicians, skillfully portrayed in the symphonic poem by Paul Dukas, which the DisneyCompany dramatized in Fantasia, while turning it into one of its brands.

.jpg)

Pointed hats make their bearers visible from a long distance and seem to have been an important sign of divinity, like the Phoenician god Baal who on statuettes generally is presented with a gilded pointed hat.

The Egyptian Pharaohs whom people worshiped as gods, wore pointed hats when they performed their official duties.

.jpg)

Christian popes also wore pointed hats and it has been said that this custom originated among bishops of Syrian Christians, who were inspired by the headgear of the Zoroastrian clergy, often called Magi. These priests had, in turn, inherited the tradition from Central Asian Scythian horsemen who lived on the steppes stretching from present Ukraine to the Altai mountains. The Scyths were well known in Europe at the time, their raids could reach as far as Denmark.

.jpg)

Thanks to the permafrost, no fewer than 140 unusually well preserved Scythian tombs have been found and their human remains were covered in magnificent costumes, often combined with huge pointed hats. What is particularly interesting with these stately burials is that one-fifth of them belonged to fully armed women who apparently were buried with the same honours as men. This might be an indication of some truth behind ancient Greek sources describing Scythian female warriors as Amazons. Several of these women also wore pointed hats.

.jpg)

During the European Gothic era, pointed hats were the high fashion among noblewomen and they were also used by the clergy, like the prominent theologian John Duns Scotus, who assumed that the "airy form" of a pointed hat stimulated his thinking. Unfortunately, his affection for pointed hats provided the name for the Dunce Cap, which was placed on the heads of failed or noisy students, who were forced to wear it as punishment for their mistakes and misdeeds.

.jpg)

.jpg)

These dunce caps might just as well find their origin in the capirote worn by Spanish penitents or the pointed hats that Jews were forced to wear during the Middle Ages, as evidence that they did not accept the Christian faith. The mix of heresy with magical knowledge is probably one of the reasons to why the pointed hat has become a hallmark of witches from the Anglo-Saxon cultural context.

.jpg)

.jpg)

By following the track of pointed hats we have thus once more ended up in the company of feared female beings, whose power was manifested during Central European mid-winter rituals. They have often been identified as witches. These ladies were generally imagined as being old hags, a denomination originating from the Old High German word hagzusa, which may have to do with the word "hedge", i.e. a border designation. Just like the Czech demon Čert's name probably meant "to draw a line", the hag could thus be considered as a liminal creature, existing close to the border line between life and death.

The origin of the word witch is easier to trace. It also comes from an Old High German word – halja-wītjan a combination of Hel, the ancient German Hell, and wītjan ”to know”, ”to understand” and a witch could thus be "someone who knows the realm of death". Witches are always women and as such, they are associated with infant mortality and missing children, and thus also assumed to be some kind of female cannibals or vampires.

.jpg)

However, this nasty aspect of the witch has been mitigated within specific cultural contexts. For example, in Italy, a witch called La Befana appears on the fifth of January (The Thirteenth- or Revelation Day) and brings with her gifts for the children. Legends told about Befana seem to associate her with the myths about child-killing witches. According to these stories, La Bafana turned into a child-snatcher after her only child had died. When she learned that God´s son was going to be born in Bethlehem she went there with the intention of killing him. But when La Befana saw the newborn baby she was overwhelmed by the beauty and grace he radiated and brought him a gift instead of harming him. As a token of gratitude, the little child declared that La Befana would henceforth become like a mother to every Italian child.

.jpg)

Now, after I have returned after my trips to Prague and Berlin and after writing about the intricacies of Czech Advent rites, I watched the horror movie La Llorona, The Weeping Lady, which is based on a well-known Mexican legend about a child-snatching ghost.

A woman who was madly in love with her husband suffered since he loved their sons even more than he loved her. When she eventually surprised her husband in flagrante with a mistress of his, she became deranged by anger and despair and drowned her sons in a river. If she was not able to retrieve the souls of her murdered sons she would not obtain any absolution from God and is now doomed to wander between Heaven and Hell. Accordingly, La Lorona now walksth rough Mexico's cities and villages, constantly crying while she snatches children from their cribs and beds to drown them in rivers and other watercourses. Like Barbora and Frau Perchta, La Llorona is white-clothed and usually covers her face.

.jpg)

.jpg)

However, La Llorona is probably far apart from her European relatives. It is nevertheless possible that this child-murdering ghost has been created from beliefs brought across the sea from the east, though I would believe that she is even more closely related Cihuacōātl, the Aztec goddess of fertility and motherhood. Although sometimes portrayed as a young woman, Cihuacōātl was more often portrayed as a tough, old woman armed with spear and shield. Giving birth was among the ancient peoples of Mesoamerica compared to warfare and women who died in childbirth were honoured as fallen warriors. But like her European equivalents, Cihuacōātl was also portrayed as a child snatcher, who haunted crossroads, or during nights sneaked into houses to steal children.

.jpg)

Likewise, the ancient, female, Mesopotamian night-demon Lilith stole infants from despairing mothers. In time, Lilith entered Jewish mythology and thus reached Europe, joining ranks with other witches.

.jpg)

Comparing customs and customs in different cultural contexts is a difficult and maybe even a futile occupation, though it cannot be denied that child mortality has been and is still a horrible reality in many parts of the world and every birth tend to be a painful and dangerous process taking place at the threshold between life and death. This has been the case during millennia and it is therefore not strange that every culture has invented protective and threatening spirit creatures believed to exist in the borderland between life and death, threatening us, but maybe also being capable of helping and protecting us.

My erratic journey that began with surgical masks as protection against a life-threatening influenza epidemy has now ended among murderous witches. Maybe it was all the time about the same thing – about protecting us from, enchanting and understanding dangers threatening us and loved ones.

.jpg)

Červinková, Petra and MonikaTauberová (2015) Onen svět. The Other World. Prague: Nárdoní Muzeum. Diamond, Jared (1997) Guns, Germs and Steel. New York: W. W. Norton. Goscilo, Helena, Martin Skoro and Sibelan Forrester (2013) Baba Yaga: The Wild Witch of the East in Russian Fairy Tales. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. Hislop, Ian and Tom Hockenhull (2018) I Object: Ian Hislop´s search for dissent. London: Thames and Hudson. Josephson-Storm, Jason A. (2017) The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity and the Birth of the Human Sciences. Chicago: Chicago University Press. McNeill, William Hardy (1998). Plagues and Peoples. New York: Anchor. McNeill, John and Garner, Helena (1965). Medieval Handbooks of Penance. New York: Octagon Books. Poe, Edgar Allan (2006) The Portable Edgar Allan Poe. London: Penguin Classics. Spinney. Laura (2017) Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World. London: Jonathan Cape. Timm, Erika (2010) Frau Holle, Frau Percht und verwandte Gestalten: 160 Jahre nach Jacob Grimm aus germanischer Sicht betrachtet. Stuttgart: Hirzel S. Verlag. Warner Marina (1994) From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and Their Tellers. London: Chatto & Windus. Warner Marina (1998) No Go the Bogeyman: Scaring, Lulling and Making Mock. London: Chatto & Windus. WHO (2017) Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report – 28 https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200217-sitrep-28-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=a19cf2ad_2

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

(2).jpg)