FREAKS: Children, dwarves, monsters and spectacles

Sometimes it happens that a tune pops up within the brain and runs like some kind of leitmotif throughout an entire day. Several years ago it was Le piano du pauvre, “the Piano of the Poor”, by Léo Ferré which placed its mark on a sunny day in Paris. A few years later, when I soaked and frozen during a raw autumn day walked through the gloomy streets of the metropolis on the other side of the Channel, it was La Fille de Londres by V. Marceau that haunted my brain. This morning while I through the heavy morning mist rode my bike along the crunching gravel road from our house in Bjärnum on my way to catch the train to town and another day at school (the longest one) it was a tune by the Swedish poets Olle Adolphson and Beppe Wolgers that popped up:

Children are a people and they live in a foreign land, this land is rain and a puddle

Over the puddle travel boys´ boats and sometimes they float so well without a keel

There goes a girl who collects stones, she has a million

The king of trees sits quietly among branches in the tree king´s throne

There is a boy who laughs at snow

There walks a girl who made an island of fifteen pillows

There, a boy and everything is ice cream that he touches

All are children and they belong to the mysterious people.

In the world of grown-ups, children are mysterious creatures. Their exoticism may be traced on the web where kids are even more popular than mischievous cats and dressed-up animals and contrary to them they are even providing web readers with some wisdom of their own, like: "Mushrooms grow in damp areas. That's why they look like umbrellas "(Henrik 8 years) or “People in love are holding hands so their rings won´t not fall off, rings cost a lot of money" (Tine 7 years), etc., etc.

Everyone who talks with kids will one time or another become amazed by the insights they are able to provide. Some of us might even remember the wonder we once felt while contemplating the strange world we live in and forget the cruelty and harshness that often are present within children’s´ habitat.

Children grow up, but the joy they provide remains. Soon, they cease to be the small, lovable creatures they once were, though nevertheless their wisdom sometimes shines through even when they have grown up. To parents their kids will remain children, even if they eventually turn into interlocutors on the same, or even a superior, level as you. Hopefully they remain emotionally attached to their old codger, bringing him messages and impressions from another world - The Fresh World of Youth. An enchanted place where so much is new, startling and exciting. While I continuously grow older my children always remain younger than I and thus inhabit a world that is different from mine.

After having been with me for a few months, my older daughter has just left me for new adventures. Sometimes we spent our evenings together by the fire place, talking about life and art in particular. She has long been active in art, design, film and theater, which means that we often deliberated about art’s importance in our modern existence. Lately, we talked about her plans to design a performance that she in lack of a better word calls a freak show. What I know write might be considered as a comment, some sort of prolongation of our discussions.

I assume a freak show was something like a circus act intended to entertain a paying audience through the exposure of deformed fellow beings. Fortunately has such depravities been discontinued within our modern and globalized societies, though some aspects of the deplorable activities have been resumed by television.

When my daughter told me about her plans for staging a "freak show" I assumed she aimed at creating a performance to highlight what is at the core of any presentation which involves at least one spectator watching someone else who acts in such a way, or who has such an appearance, that the observer becomes interested. A relationship mirroring the dichotomies that govern our lives and thinking – the observer and the observed, subject and object, me and “the other”, insider and outsider, center and periphery, cosmos and chaos, normality and abnormality.

Who is a freak? Who are the most common freaks? Maybe dwarfs? Dwarfism is such a conspicous condition that persons suffering from it have in most cultures and epochs attracted curiosity, jokes and fantasies from their fellow human beings. Since people generally grow from childhood to adulthood, dwarfs end up in a kind of permanent intermediate position where they do not belong anywhere. Small adults have seldom been considered as “ordinary people” who just happens to be short, instead they have been deemed as outsiders, as a separate human specimen. Since art tends to provide an alternative view of the world, dwarfs have often been consigned to that sphere. Writers, artists and people engaged with create performances of various kinds, like theatre and movies have accordingly often claimed dwarfs as their belongings, stressing their “otherness” and providing them with a specific moral and aesthetic significance. Dwarfs have thus become the “standard” freaks/outsiders of art, literature and performances.

Nowadays, dwarfs seldom appear in circus and I suspect that this state of affairs has bereaved some of them a traditional livelihood. However, I assume that society now is willing to allow genetically damaged people to find their proper place in society, meaning that they on equal terms with any other citizen are provided with opportunities to contribute to the public good in areas where they feel comfortable and have the most to give.

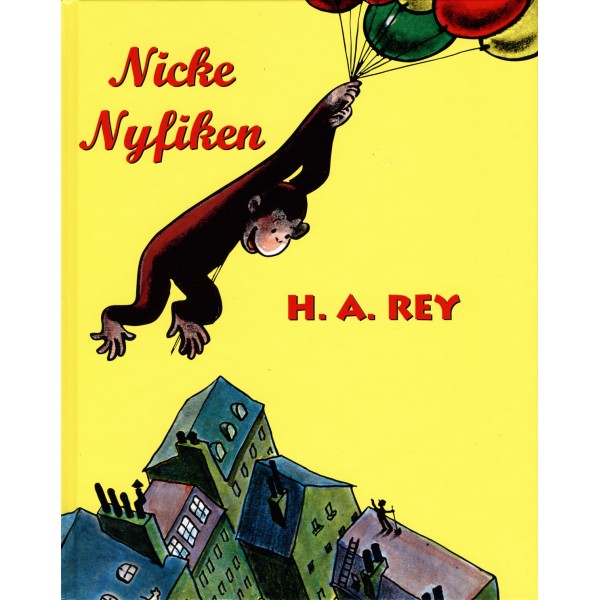

Like other persons who have an appearance, or specific characteristics, distinguishing them from others, it may be possible for individuals affected by genetical disorders to gain a comparative advantage in competition with individuals considered as being "normal." This is an insight that I have not reached on my own, but many years ago was taught by a student of mine who was a dwarf. She told me that she had always suffered from people’s insensitivity and senseless cruelty and in order to overcome her feelings of sorrow and alienation she was making an effort to accept her “abnormality” as an undeniable fact and trying to transform it into a base for a specific way of life. She told me she wanted to begin a career within the circus, or the movies, though I don´t know if she ever got there. She gave me a book about Curious George.

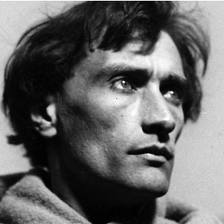

A famous and successful actor who due to his stature is forced to accept roles specifically suited for dwarfs is Peter Hayden Dinklage, who has achieved great popularity due to his interpretation of the character Thyrion Lannister in the TVseries Game of Thrones. Thyrion Lannister is an appealing character; intelligent, astute, witty and a great charmer of women, nevertheless Thyrion is acutely aware of the fact that he is a dwarf and disdained by others due to this condition. His portrayer, Peter Dinklage, is is often asked about his importance as a role model and spokeperson for dwarfs:

I don't know what I would say. Everyone's different. Every person my size has a different life, a different history. Different ways of dealing with it. Just because I'm seemingly okay with it, I can't preach how to be okay with it. I don't think I still am okay with it. There are days when I’m not.

When asked about his condition and how it has affected him, he answered:

When I was younger, I definitely let it get to me. As an adolescent, I was bitter and angry, and I definitely put up these walls. But the older you get, you realize you just have to have a sense of humor. You just know that it's not your problem. It's theirs.

It is no longer considered to be politically correct to allow yourself to be entertained by people just because they are deformed in comparison with “normal people”. The freak shows, after having been forbidden in England for almost fifty years, began to disappear from the US in the 1920s. The changing attitude to such exhibitions became apparent through the shocked reaction to Tod Browning´s movie Freaks, which was released in 1932. Even if more than thirty minutes of the most horrific sequences had been cut (and lost forever), moviegoers in general were appalled by what they saw. Freaks was quickly removed from the repertoire and in England it was for more than thirty years banned from public screening. The career of Tod Browning, who had had a great success with his 1931 movie Dracula,derailed completely due to the reception of Freaks, though cineastes rediscovered the movie in the early 1960s and it was hailed as a masterpiece at the 1962 Cannes festival.

Many have marveled at how Tod Browning could be able to use people who were severely malformed in a commercial horror film production. One explanation may be that he already at the age of sixteen ran away from his wealthy family and for several years worked in circuses, where he became well acquainted with many of the freaks who at that time appeared in circuses and itinerant market shows. People who despite the misery and alienation they often were forced to endure, could find a place and some respect among the rootless artists and odd characters that made a living within the circus world. Freaks is still a shocking movie and I became quite upset while watching it. Although the freaks are depicted as generous and warm-hearted people, they nevertheless take a gruesome and grotesque revenge on the two "normal" members of the circus troupe, those who through their malice and moral rottenness are the real monsters. The freaks assault and injure their tormentors to such a degree that they turn them into freaks as well.

The fact that anyone, through accidents and injuries, can change into being a "monster" became apparent during and after the First World War, when several soldiers returned from the hell of the trenches maimed and wounded in both body and soul. What soldiers most of all feared, even more than death, was the risk of having their faces disfigured. Something that is easily understood if confronted with clinical pictures taken of facial injuries.

The face is the part of the body considered to reveal the most of our personality and if it becomes damaged it will affect the impression we give to people around us and thus our own soul, as well. This is a theme which with an inexorable logic is raised in a frightening short story, The Monster, by Stephen Crane. It tells the sad story of a righteous and kind, black coachman, Henry Johnson, who works for a small-town doctor. Henry becomes horribly disfigured when he saves his employer's son from a burning house. Henry's altered appearance frightens and disgusts the locals who start to avoid him and call him a monster. When the good doctor insists in taking care of the man, who so heroically has rescued his son, it results in him and his entire family becoming ostracized and isolated from society. The doctor loses his practice and cannot, against his conscious will, help nursing a resentment towards the tormented, but awful looking, Henry Johnson.

How a kind and well-intentioned man is forced to live enclosed inside a disfigured body is also masterfully depicted by David Lynch in his film The Elephant Man, based on Joseph Merrick's tragic life. The severely deformed Merrick, who, after being beaten and bullied by an unsympathetic environment, not the least members of his own family, was approached by the renowned Victorian impresario Tom Norman, who exhibited him in a trinket shop opposite the London Hospital. Among the young physicians fascinated by Merrick´s malformations was a certain Fredrick Trevis, who found that Merrick was a likeable and intelligent man.

When freak shows in 1886 were banned in England, Merrick moved to Belgium but ended up handled by a merciless ruffian who mistreated him, behaving as if Merrick had been a soulless beast. Merrick managed to escape and was able to seek Dr. Trevis´ help and support. The doctor took care of him, until Merrick died at the age of 27. The head had become too big for Mr. Merrick´s weakened body; its weight broke his neck while he slept. His skeleton is still preserved at the Royal London Hospital and a bizarre episode in the tragic story of Joseph Merrick is that in 1987 the famous artist Michael Jackson tried to buy the skeleton. It is possible that Jackson at some level identified himself with the unfortunate and marginalizedJoseph Merrick. Jackson was often accused of being an eccentric, both as an artist and a human being. Freak was an epithet frequently thrown upon this artist who, whatever one thinks of him as a person and artist, undeniably was a genius, arevolutionary innovator in both dance and music.

That contemporary science was interested in Joseph Merrick´s condition is not surprising. Racial anthropology was in vogue after Darwin's revolutionary findings. Both human appearance and psyche were studied intensively, often in a manner that did not pay much attention to the personal feelings of “the human specimens” who became objects of “scientific investigation”. "Primitive people" were stripped naked, measured and photographed and were like wild beats often exhibited to paying customers, generally within a framework presented as “scientific and educational”. Similarly, were mental patients transported into lecture halls so students and a paying audience could study their peculiar behavior. Particular attention was paid to Jean-Martin Charcot's public displays at La Salpêtrière hospital in Paris where visitors flocked from all over Europe to see how the renowned physician hypnotized hysterical women.

Many onlookers have testified to the dramatic atmosphere that prevailed during Charcot´s sessions and mention the doctor's "magnetic acting talent." Like in a theater, Charcot underlined the importance of paying attention to the facial expressions that accompanied the hysterical females´ body language. The faces of mentally disturbed persons have intrigued both researchers and artists. As I mentioned above, the face has generally been considered as a mirror of the soul, something that fascinated great artists like Théodore Géricault and Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, the latter obviously found himself at the brink of insanity.

A person's relationship with his own face is treated in an original way by the Japanese writer Kobo Abe, who in his novel Face of Another describes how a plastic surgeon has his face disfigured through an accident. His face is re-created, but problems to join the tissue properly to the muscle attachments result in a rigid, insensitive expression to the doctor´s reconstructed features. The surgeon becomes a stranger to his own face. When he looks into a mirror he confronts another person and is shocked when he finds that his wife treats him in a completely different way than before he suffered the accident. She appears to be more attracted by him. Instead of feeling reassured after having his looks restored, the doctor turns into a split and desperate man, experiencing how his new face has transformed him into a person he does not want to acknowledge.

It is possible that Tod Browning´s film and all the commotion it caused was one of the last nails into the coffin of American freak shows, though the concept lingered and is now frequently used to label many of the ever more popular “humiliation TVshows”, which want us to laugh at people who in front of the cameras are making fools of themselves and others.

The Swedish-Italian film director Erik Gandini has made a relentless documentary,Video Crazy, depicting the distasteful madness that has spread all through the Italian television networks after they have been poisoned by Berlusconi's gross populism. Several agonizing examples of humiliation are presented, like housewives stripping in the incredibly vulgar entertainment program Colpo Grossoor how young girls humiliate themselves in desperate attempts to be chosen asveline, scantily dressed girls who without talking make sensual dance movements during short breaks in brain dead spectacles. The most painfully pathetic scene in Gandini´s documentary is when a not particularly attractive middle-aged woman performs an unbelievable inept striptease in front of a frosty group of unsmiling media despots.

There are numerous varieties of humiliation TV. Examples are becoming countless. I will name a few to suggest what I'm referring to: Big Brother, where people are looked up in a confined space only to plague and humiliate each other, America's Next Top Model, where youngsters are cynically judged and chastened by a distasteful bunch of "successful" self-inflated and obscure luminaries, a show comparable to several similar degrading events, like The Apprentice, a program where a millionaire insults youngsters searching for an employment obtains, particularly in these times of mass unemployment among young people, an additional level of cruelty. And then there are all these tasteless horror spectacles where people are forced to disgrace themselves through their efforts to attract the attention of repugnant “celebrities” like Hugh Hefner or Paris Hilton. The X Factor, where we are welcomed to laugh at talentless wretches exposing themselves to the ruthless limelight in frantic attempts to become admired idols, or America'sFunniest Home Videos where we are entertained by children and animals being hurt or mistreated. Extreme Makeover, which sells a concept indicating that gray sparrows who are dissatisfied with their looks after submitting themselves to the magic treatment of some idiotic media pixie will, like frogs in fairytales, be turned into a coveted princess. And then all those idiotic mating shows where unsuspecting couples wallow in tastelessness within the confines of a vulgar luxury “paradise”.

There are also a kind of politically correct freak shows, which according to their producers provide disabled persons with pride by giving them an opportunity to test their abilities in extreme situations, or just present themselves as the woman or man next door, thus enabling them to prove their human dignity to the common crowd. Examples are Push Girls featuring a group of wheelchair-bound women;Little People, Big World, which follows a family of six where two of the children are giants and two are dwarves; Beyond Boundaries, where a group of disabled young people are traveling around the globe while overcoming difficult challenges like mountain climbing and wilderness survival; The Undateables where dwarves, giants and other people with genetic disorders who are craving for love and understanding are presented in groups and through various life situations andSeven dwarves, which follows professional dwarf artists. There are also distasteful "documentary shows" that flatly ignores decency and compassion, like Body Shockpresented on England's Channel 4 and featuring misshapen individuals like the world's smallest, tallest or fattest man, the man with a 63-pound testicle, people with mega tumors, twins who share a brain, the girl with eight legs, etc.

To consider misfits or misshapen persons as both outsiders and providers of entertainment seems to be as old as man. I have often wondered how the so often admirable Romans of classical times, who in their writings occasionally give an impression of being our contemporaries, could appreciate the sight of fellow human beings being tortured, torn apart and killed on bloodstained arenas. When I read Ovid´s advice on how to approach desirable ladies during gladiator shows (you could for example bring along a comfortable cushion and offer it to them), or Seneca's complaints about how young people show-off and make noise in the public baths, it makes me think that you might any day pass by such individuals in the streets of Rome. Nevertheless, when I am confronted with the mighty Colosseum brooding over the city, it turns into an eerie reminder of how popular human slaughter under festive circumstances once was. Sometimes, the old Romans seem to be levelled, just and interesting people, harboring the same fellings as most of us have today, but often their lack of compassion with fellow beings seems to have been extreme.

How could that be? What surprises me is that writers like Seneca and St. Augustine condemn the cruel entertainemnt of the arenas, but apparently without expressing any thought whatsoever about the sufferings of the hapless participants. Apparently they regard the bloody games as nothing else than a form of distraction unworthy of an educated and civilized man. St. Augustine, for example, writes about his student Alypius who had become obsessed with the excitement of gladiatorial games:

He was very fond of me for what seemed to him my good conduct and learning, and I loved him for his innate virtue, which was evident from an early age. Yet the moral maelstrom of the Cathage had sucked him in, seething as it was with frivolus entertainments and especially with the craze for games in the Circus.

Augustine came to consider Alypius as a lost case, but one day the young man unexpectedly showed up during a rhetoric class. Augustine, who was commenting on a text the students had read, immediately seized the opportunity to lecture Alypius:

The text I happened to be expounding suggested a fitting connection to the games. To make my point clearer and fix it in the mind with laugther, I described satiraically those held in thrall by that madness. [...] [God] You "blew on my heart and lips as burnijng coals" by which you cauterized and cured a mind with good propects from its self-inantion [...] After that I said, he wrenched himself from the deep pit into which he had eagerly plunged, blinded by his weird delights. With determination he took a grip on himself, the filth of the games was rinsed awas, and he stopped going to them.

It sounds as if St. Augustine had cured his student from a gambling addiction, rather than rescued him from a morbid interest in watching people being murdered. For an educated Roman, empathy did apparently not reach beyond your closest relations. For example, Seneca was a skilled comforter of those among his friends who had lost a beloved son, father or wife, but apparently did not have much compassion for wretched slaves, or those who, on an almost daily basis, were sacrificed in the arenas all across the Empire. He writes to friend of his that it is inexplicable that a man of his learning and refined tastes could lose his money and time on such a vulgar diversion as owning a private gladiator troop. In a letter to his friend Lucilius, Seneca describes a visit to "the games":

The other day, I chanced to drop in at the midday games, expecting sport and wit and some relaxation to rest men's eyes from the sight of human blood. Just the opposite was the case. Any fighting before that was as nothing; all trifles were now put aside - it was plain butchery. The men had nothing with which to protect themselves, for their whole bodies were open to the thrust, and every thrust told. The common people prefer this to matches on level terms, or request performances. Of course they do. The blade is not parried by helmet or shield, and what use is skill or defense? All these merely to postpone death. In the morning men are thrown to bears or lions, at midday to those who were previously watching them. The crowd cries for the killers to be paired with those who will kill them, and reserves the victor for yet another death. This is the only release the gladiators have. The whole business needs fire and steel to urge men on to fight. There was no escape for them. The slayer was kept fighting until he could be slain. "Kill him! Flog him! Burn him alive!" (the spectators roared) "Why is he such a coward? Why won't he rush on the steel? Why does he fall so meekly? Why won't he die willingly?" Unhappy as I am, how have I deserved that I must look on such a scene as this? Do not, my Lucilius, attend the games, I pray you. Either you will be corrupted by the multitude, or, if you show disgust, be hated by them. So stay away.

What Seneca describes are not any regular gladiatorial battles, but some kind ofinterludes offered in the middle of such spectacles, involving various forms of killing people sentenced to death - they were thrown naked in front of furiousbeasts, forced to fight to death, or were killed in bizarre tableaux alluding to classical myths; Marsyas being skinned alive by Apollo, Prometheus who still alive had his liver devoured by a vulture, Polyphemus getting his eye gouged out by Odysseus and his men, etc. Such spectacles were according to Seneca and Cicero pitiful and disgusting. What the two philosophers, however, appreciated were the bloody battles between trained gladiators, They extolled their bravery andstrength, considering that lazy Roman citizens ought learn something from the gladiators´ contempt for death. They did not comment on the fact that such battles were fought by slaves without any other options than life or death.

Art history presents numerous examples of how freaks, dwarves and other “odd creatures” were selected to act as buffoons, or just by their presence, as providers of merriment and laughter within the mansions and courts of Europe.

For example, Peter the Great of Russia surrounded himself with an impressive entourage of dwarfs. When his favorite dwarf, Yakim Volkov, married in 1711, he organized a sumptuous feast:

The tsar […] had instructed Prince-Caesar Romodanovsky to round up all the dwarfs in Moscow and send them to St Petersburg. Their owners were told to provide smart outfits for the dwarfs in the latest Western fashion, with plenty of gold braid and periwigs […] On the day about seventy dwarfs formed the retinue for the wedding ceremony, which was accompanied by the stifled giggles of the full-sized congregation […] a spectacle made all the funnier by the fact that most of the dwarfs were of peasant extraction with coarse manners. At the feast […] the dwarfs sat at miniature tables in the centre of the room, while full-sized guests watched them from tables at the sides. They roared with laughter as dwarfs, especially the older, uglier ones who hunchbacks, huge bellies and short crooked legs made it difficult for them to dance, fell down drunk or engaged in brawls.

Perhaps there was previously a lesser sensitivity towards the suffering of “others”, something that probably was not so strange in a society where public executions and mutilations were a common distraction from the daily toil, where there was a big difference between people and people, and the suffering and poverty certainly was bigger than it is now, at least in places like Europe and America. While considering peculiar spectacles like that of Peter the Great, it is also the possibility that the dictatorial powers of privileged classes and individuals limited their ability to feel empathy.

Without doubt did ruthless dictators like Hitler, Stalin or Mao have serious shortcomings when it came to empathy and compassion. Hitler ranting in his Berlin bunker that “The German people have not fought heroically. It deserves to perish […] it is not I who have lost the war, but the German people” or Stalin muttering to his secretary, while he routinly is signing a number of death sentences: “Gratitude is a sickness suffered by dogs”. Mao´s physician Li Zhisui wrote:

So far as I could tell, Mao was devoid of human feeling, incapable of love, friendship or warmth. Once, in Shanghai, I was sitting next to the chairman during a performance when a child acrobat was seriously injured. The crowd was transfixed, and the child's mother was inconsolable. But Mao continued talking and laughing, as if nothing had happened.

Yet another spectacle. As an art form circus includes the possibility of death and disaster. Acrobats, knife throwers, the tightrope walker high up under the dome, trapeze artists and the lion tamer all live dangerously. Performing artists, or the misshapen freaks, are targets for their spectators´ attention, objects for their approval or criticism; their assessments, anticipation and pleasure. In a way the audience is the monster; watching, lurking, evaluating. The word “monster” originates from the Latin moneo, "to recommend, show, or warn". The monster is stating something; it expresses some kind of warning. But for what? For ourselves? For our emotions? In any case, it makes us uncomfortable, but at the same time it exerts some kind of allure. As Nietzsche wrote in Beyond Good and Evil:

He who fights with monsters might take care lest he thereby become a monster. And when you gaze long into an abyss the abyss also gazes into you.

Maybe it amuses us to see chimpanzees dressed up as humans, to watch dwarves who appear to be both children and adults, or clowns who in their absurd outfits hold up a laughing mirror in front of us - they are like us and yet not like us. However, it is perhaps all an delusion. Maybe it's I who am a monster, at the same time a perpetrator and a victim? The fun stops as soon we realize the monster's humanity, empathy is killing the laughter and we end up on the other side of the ramp, feeling watched and assessed:

Elephants in the circus

Have aeons of weariness around their eyes.

Yet they sit up

and show vast bellies to the children.

The scene turns, we end up as the humiliated clown, the mistreated freak. At the other side of the ramp where Verdi's Rigoletto and Leoncavallo´s Beppo express their pain through song, or Alban Berg's degraded and disorientated Wozzeck exclaims his heartbreaking Wir arme Leut, we poor Humans. Or we confront the brutal, emotionally crippled Zampanò in Fellini's magnificent La Strada. Where we also find the even more heart breaking and pathetic monsters created by Victor Hugo - the hunchback Quasimodo and Gwynplain, “The Man Who Laughs”, who both die with all their pain locked up within themselves. There are also the bewildered outcasts, the often repulsive practitioners of great art, what Jean Dubuffet called l'Art Brut, Outsider Art. Antonio Ligabue wandering between Switzerland and Italy, in and out of daytalers´ wretched lodgings or mental hospitals, while, after he had dressed up as a woman and performed magical rituals, painted masterpiece after masterpiece.

Or the deaf-mute Nikifor, born by an equally deaf-and-dumb beggar woman, who in wartorn Poland wandered from village to village trying to sell his remarkable paintings.

Those are things I and my daughter have talked about by the fire place during the past evenings. What is art? What is theater? We discussed the distinction between performer and spectator. The division that Antonin Artaud wanted to wipe out through his "Theatre of Cruelty". In a collection of essays called Le théâtre et son double, “The Theatre and its Double”, Artaud declared that he wanted to create a theater completely different from the general practice of performing in front of passive spectators. He wanted to force the audience up onto the scene, or make it engulfed by the spectacle in such a way that "their nerves and hearts" became involved in the “grim spectacle of existence”. The audience had to be inspired by the performance´s "fiery magnetism" in such a way that the experience could never be forgotten. A theatre performance had to be like a spasm in which life is “lacerated”, where all creation rises up and challenges the imaginary social status created by ourselves. With "cruelty" Artaud meant he wanted to create a kind of theatrical performance where the viewer becomes defenseless and feels attacked, rather than distant and protected. Artaud´s ideas and desperate actions brought him to the brink of insanity. Perhaps it is, after all, best to distinguish between life and art, and thus avoid to be incinerated in a futile quest for a union between life and creation.

It is probably enough to take an occasional refreshing dip into art´s wonderland. After all, most of us are not condemned to live within a dwarf´s or giant's body and through no fault or our own be subjected to ridicule and contempt. We do not find that our desperate attempts to gain recognition and notoriety only leads to defeat and humiliation, as the wretches who are abused by the reality shows´ distasteful spectacles. We are not like the great masters of l'Art Brut whose art often was appreciated only because it was created by poor eccentrics.

The world of Art is certainly often a theater of cruelty, but it is also a refreshing source that suddenly may gush forth among the toil of every day’s dull cares and routines. It enters like an exotic stranger showing up with a bag of tricks.

Art is not only present in a painting or a theater production, it thrives in a child's smile and thought-provoking questions, within a spirited conversation with a wise daughter, or a melody that pops up during a bike ride to work. The poet Lars Forssell, who made the excellent translations of the songs of Léo Ferré and V. Marceau I was thinking of by the beginning of this blog entry, knew that poetry and art are always with us, even if we cannot always perceive their presence:

You say that poetry is dead, or at least dying,

but then you forget, my well-fed friend, that it lives like you

as neighbor with death

a few steps down

the creaking steps

there in the dark.

The bricklayer sings,

the carpenter sings,

the cashier at the supermarket sings,

ministers and opposition

and you and I and the gravedigger,

everyone sings for life.

All yelling and singing for life.

Until he a few steps down below

knocks on the ceiling with his cane!

The poem about elephants at the circus was written by D.H. Lawrence. Unfortunately, I had to translate the Swedish poems by myself, ignoring rhyme and rythm. Other sources were: Abe, Kobo (2003) The Face of Another. New York: Vintage. Augustine of Hippo (2008) Confessions. London: Penguin Classics. Crane, Stephen (1993) The Open Boat and Other Stories. New York: Dover Publications. Drimmer, Frederick (1985) The Elephant Man. New York: Putnam. Kois, Dan (2012) “Pieter Dinklage was smart to say no “, in The New York Times, 29 mars. Hughes, Lindsey (2002) Peter the Great: A Biography. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Artaud, Antonin (1958) The Theatre and Its Double. New York: Grove Weidenfeld. Skal, David J. and Elias Savada (1995) Dark Carnival: the Secret World of Tod Browning, Hollywood's Master of the Macabre. New York: Anchor Books. Seneca (1969) Letters from a Stoic. London: Penguin Classics. Zhisui, Li (1994)The Private Life of Chairman Mao: The Memoirs of Mao´s Personal Physician. London: Random House.