WHAT YOU MIGHT FIND IN THE BROTHERS KARAMAZO

I have now reread Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov. Reread? Why? Isn't that a waste of time? The novel contains more than 800 densely written pages! Well, why not? It has been more than 50 years since I read it and I was wondering if it would still fascinate me as much now as it did then. Who was that boy who read it so many years ago? I must have been more or less sixteen years old. Could I, like this considerably older reader, really have understood and realized the subtle nuances of this strange masterpiece? Probably not. However, that young man must have read it in his own manner and been enthralled in a completely different way than the old man who has read it now.

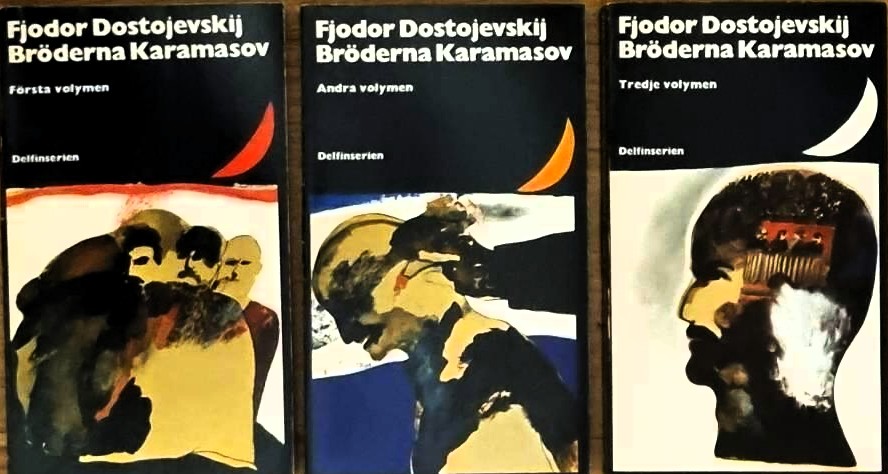

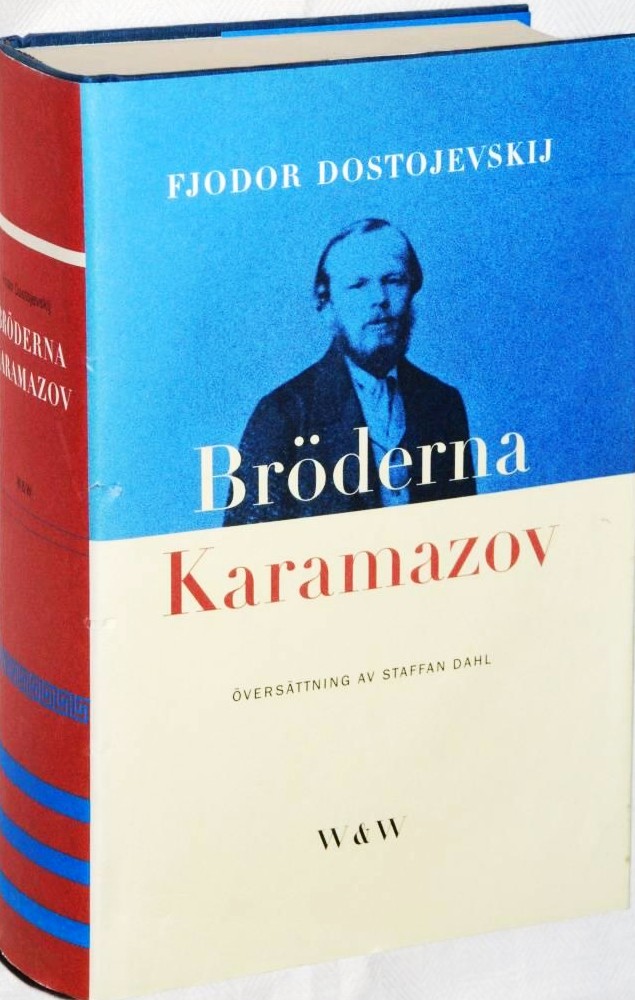

You have to take into account that I when I read it so long ago it was in Ellen Rydelius’ aged, though somewhat updated, Swedish translation and not in the admirable version published by Staffan Dahl in 1986. I am not familiar with any English translations.

I remember quite well how I was introduced to Dostoevsky. Like so many of us, I was found myself in the the so-called “devouring age” and in quick succession I read book after book. I don’t understand how I managed to read so much, on top of school and the games my friends and I played in the yards around the apartment building we lived in.

It was an unsorted reading. I read all the Deerfoot books I could find, James Fenimore Cooper, Jules Verne, and Karl May. I reread some books several times, such as Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines and Montezuma’s Daughter, Stevenson’s Treasure Island, and Maryatt’s The Privateersman, as well as Nordhoff and Hall’s Mutiny on the Bounty. At the same time, I was a constant reader of various comic magazines such as Donald Duck & Co. and The Phantom.

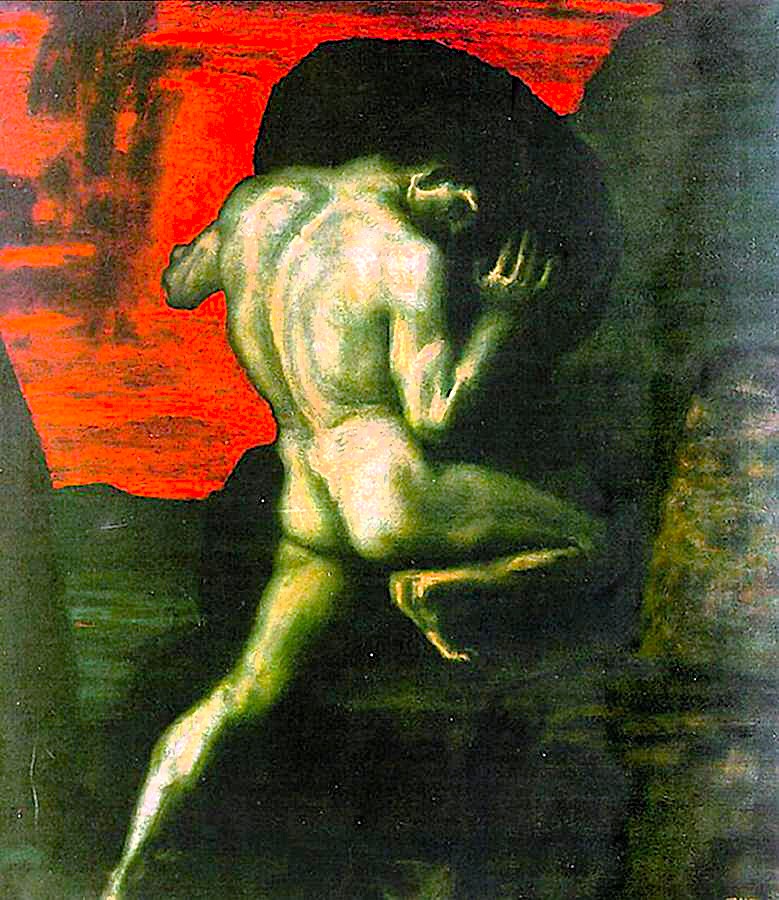

.jpg)

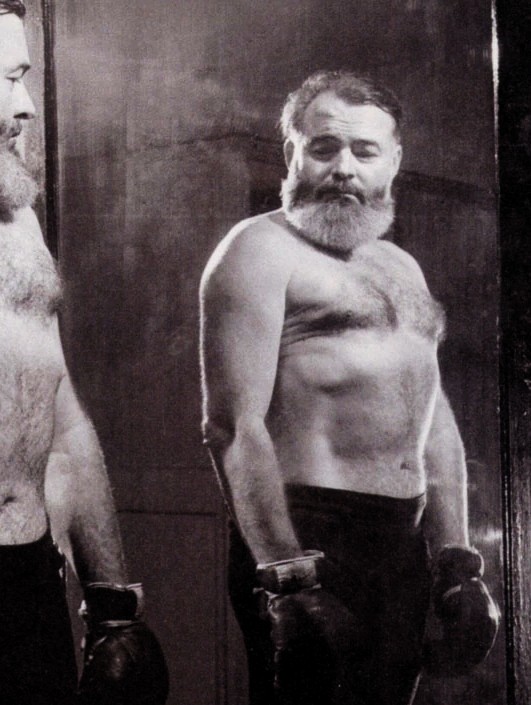

I was certainly embarrassingly precocious. Now I have a hard time understanding how I could absorb so much reading and find it strange that I even found pleasure in reading the Bible; perhaps it was my grandfather’s influence that made me read it, without finding it neither incomprehensible, nor boring. It is possible that this was the reason to why my father one day, when I was sick in bed with a fever, decided that it was time for me to read “adult literature”. I still remember which three books he gave me – The Old Man and the Sea, Land of Wooden Gods by the Swedish author Jan Fridegård and ... Crime and Punishment. I have also reread the latter and each time I was engrossed in Raskolnikov’s feverish madness

.

.

A few years later I read The Idiot, even if I still remember several scenes from that novel, I was not as taken by it as I had by Crime and Punishment. The Brothers Karamazov was different, an intricate labyrinthine world in which I got lost for a couple of months. I found several sections long-winded, but the descriptions of the characters stuck in my mind, just as Raskolnikov had done earlier. However, I found Alexei/Aljosja somewhat silly in his too perfect pious appearance.

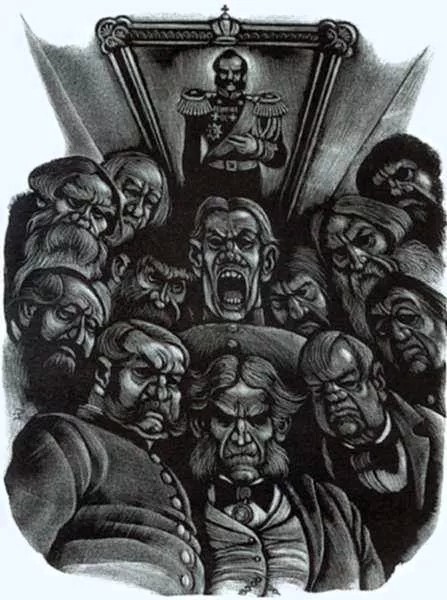

Now when I have reread the masterpiece, as said before, I cannot really remember how I perceived it as a young man, now – exactly 53 years later – reading it carefully I did, just as in those days, its scenes in front of me as if I was watching a film. It was precisely this strange visual palpability that took hold of me once again, but this same time I was surprised by how much dialogue there is in it. I found how all the characters spoke in different ways. How each of the brothers as well as their father, were characterized by their use of language. How differently the ladies – Grushenka, Katérina and Chochlakova expressed themselves. I found that these women, to a greater extent than the men, seemed to be even more theatrical than the men.

.jpg)

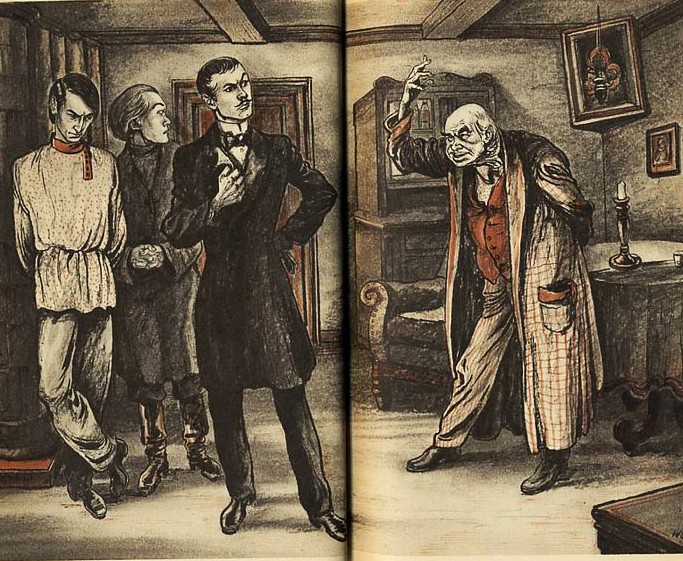

Every character in the novel displayed a multidimensionality portrayed in a subtle and masterful manner. Even the foolish philanderer and despotic Fjordor Pavlovlitch, this wretched and later murdered father, exhibited mitigating traits that occasionally, despite his obvious wretchedness, could arouse a certain sympathy

.

Likewise, Smerdyakov, this Dickensian character – a caricatured, strange, sly and generally despised figure, with vaguely sadistic tendencies – he too became understandable and could thus appear to the reader as more intelligent than he was to the other characters in the novel, and so, like many of them, he emerged as a rather tragic person.

No one, not even the supporting characters – petty officials, innkeepers, retired soldiers, farmers, doctors, children, etc. – who populate this teeming novel appear as superficially portrayed staffage. The Brothers Karamazov was Dostoevsky's last novel, and in it he put all the keen observation he had cultivated throughout his life. A thorough knowledge of humanity that he had established when, during his four years as a convict in Siberia, he had studied his fellow prisoners and listened to their stories. A hellish time depicted in House of the Dead.

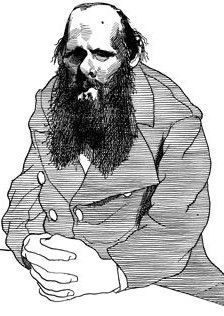

Dostojevsky’s role playing, his ability to empathize with his characters, might be compared to any character actor, such as the greatest masters of Stanislavsky’s system, or Strasberg's method acting. Epileptic seizures and drunkenness contributed to his ability to transform personal experience into great art. Not to mention the life-changing and terrifying experience before and during his mock execution, which took place after he had been sentenced to death for his involvement with the radical discussion club the Petrashevsky Circle.

Hemingway, who devoured Russian literature but was probably a greater admirer of Tolstoy than of Dostoevsky, claimed that it was the Russian writer’s difficult time as a Siberian prisoner that turned him into a truly great writer: “Writers are hardened by injustice, like a sword is forged.” A view that Hemingway shared with Nietzsche, who in a letter wrote to his friend Peter Gast that after reading a French translation of Notes from Underground, he had been seized by a

sudden awareness that one has met with a brother. . . . four years in Siberia, chained, among hardened criminals. This period was decisive. He discovered the power of his psychological intuition; what's more, his heart sweetened and deepened in the process. His book of recollections from these years, La maison des morts, is one of the most “human” books ever written. [...] I first read [...] two short novels [“The Landlady” and Notes from Underground]: the first a sort of strange music, the second a true stroke of psychological genius—a frightening and ferocious mockery of the Delphic “know thyself,” but tossed off with such an effortless audacity and joy in his superior powers that I was thoroughly drunk with delight

I believe it was the mock execution that most strongly marked Dostoevsky’s life and writing. It was then that he realized that his entire existence was threatened and that it soon would end. The idea of the meaning of life and the existence of God appeared in a sharp, frightening light. At the last second, however, he was freed from death and taken to a Siberian hell. It was there, while he was forced to live close to other unfortunate people, that Dostoevsky came to realize what I have found in so many of his books – that it is our current, earthly existence that is the real Hell. Or perhaps rather a Purgatory where, in the shadow of Death, we are forced to choose between total meaninglessness and salvation through an unwavering faith in the teachings of Jesus and a certainty of God's divine grace

In The Brothers Karamazov, the reader is inexorably drawn into Dimitri's nightmarish wanderings on the night of the murder and the subsequent orgy of drunken revelry. We are forced to take part in Dimitri's confused state of anxiety, just as in Crime and Punishment as we were following Raskolnikov on his incongruous wanderings through the streets of St. Petersburg. For me, reading this became a kind of intoxication, as if instead of reading a novel I were downing glass after glass of wine.

What struck me during my re-reading of The Brothers Karamazov was the narrator's voice; intrusive and omniscient, while he emphasizes that he is part of the small town he is describing. Yet he remains in the background the whole time.

In Dostoevsky's company, the reader enters a world that appears to be both foreign and domestic, the latter through his deep-drilling visits into the characters’ minds. Dostoevsky manages to see the world through the eyes of his characters, without losing control of his story, its flow. Side stories intervene and make the reader wonder about their justification, but it soon becomes clear that they illuminate the main events and deepen them – like the life story of Father Zosima, or the tragedy of little Ilya.

This is an author who has mastered his difficult craft and does not lose control of his story’s multifaceted unpredictability. Well, maybe when at the end he on page after page allows the prosecutor to carefully explain what the reader is already familiar with, it was only here that I for a moment lost patience and slipped out of Dostoevsky's secure grip.

Otherwise, the trial scenes provide an excellent conclusion to an intricate murder story, with crucial details and unexpected twists, a courtroom drama worthy of a Perry Mason episode and certainly experienced by Dostoevsky during his own trial visits and diligent newspaper reading.

The novel provides a depiction of Dostoevsky's own spiritual struggle. I assume that several readers have been blinded by the angelically meek Alyosha, although Dostoevsky made him his hero, he occasionally exhibits human weaknesses. However, this does not prevent him from occasionally, at least to a reader like me, appear as being too good to be true. If one considers Alyosha as Dostoevsky’s alter ego, in whom he seeks to present the Russian Orthodox faith as a victory over doubt and nation-destroying nihilism, I believe that the reader loses much of the strength of this astonishing novel.

Several readers have found Dostoevsky’s characters to be puppet-like, something I cannot agree with. Perhaps they can sometimes appear to be somewhat too grotesque, like several of Dickens’ odd personalities, Dostoevsky's characters can hardly be described as “puppets”, passionate and odd - yes, but if had they been as one-dimensional as some critics have claimed, they would not have remained in the memory to such a degree as they do.

Dostoevsky has also been accused of having a clumsy, unpolished and clumsy style. I don't know any Russian, though I cannot agree with such an opinion, at least if I judge from Staffan Dahl’s Swedish translation, through which I believe to hear how different Dostoevsky’s characters express themselves, how their voices and language are constantly changing.

It has also been said that Dostoevsky's conservatism, his pan-Slavic orthodox thinking and generally intolerant attitude towards people from other nations, comes forth in his novels. I did not find much of that in The Brothers Karamazov, there is a negative description of a couple of unpleasant Poles and a nasty depiction of a Jewish ritual murder, but I did not get the impression that Dostoevsky made such a big deal out of it and the ritual murder was not presented as something the narrator believes in, rather it was based on an inappropriate newspaper article. As for the religious sentiment, it is of course there. However, it does not dominate, does not stifle the appearance of neither the plot nor the novel’s characters. Dostoevsky’s religious beliefs do not appear to be pamphleteering or bigoted. There is a lot of soul-ache and searching to meaning; human feelings tarnished by acting, contempt and hatred, but also sincere love and compassion.

A reader might just as well as making Alyosha into his/her hero, identify with the passionate Dimitri in his life-affirming enthusiasm and violent loves. While he immerses himself in paralyzing mental anguish, violent self-reproach and startling naivety, Dimitri remains a person who is appreciated and loved by many. Of course, Dostoevsky’s novel, with its varied gallery of characters, its passionate love story, murder and detective work, its comprehensive depiction of society and sometimes heart-wrenching sentimentality, not to mention its lively dialogue, has attracted a number of film adaptations. Speaking of the intense Dimitri, I come to think of Richard Brooks’ interpretation of The Brothers Karamazov from 1958. It is quite good, with Yul Brynner as Dimitri. A central figure by whose side the brothers Ivan and Alexei fade away. Yul Brynner offers one of his best performances, despite his somewhat exotically wild woodenness, enlivened by his darkly arousing glances. Brynner’s Dimitri has nevertheless remained on my retina and in my mind and has thus become an image of how I imagine Dimitri.

Of course, it will not be feasible to perfectly adapt a work as stylistically, multifaceted and psychologically nuanced as The Brothers Karamazov, but several of the cinematic attempts that have been made to do so have not been so bad at all, probably due to the novel's rich dialogue and first-class visuality. For example, I was quite impressed by the two Russian adaptations I have seen. Lavrov, Pyrev and Ulyanov’s more than three-hour version from 1969 is quite good and its characters interpret my perception of the book's personalities in a commendable manner . For example, the three brothers:

And not the least Smerdjakov.

A 12-episode Russian TV series followed the story in great detail. It is beautiful to watch, filmed as it is in a typical Russian monumental style, though in my opinion it is, when it comes to the character development it is considerably weaker than the 1969 movie.

Speaking of film, I remember when I was lucky enough to study film under Sverker Hällen at the University of Lund. His teaching gave me a deeper appreciation of the craft of filmmaking. Sverker knew Russian and was a great connoisseur of Russian culture. At one point he had printed out The Brothers Karamazov's depiction of Dimitri’s feverish activities in his father’s garden at the night of the murder. Sverker asked us to make a movie synopsis to depict the sequence of events in great detail, indicating lighting, camera angles, editing and rhythm. The variations became varied and the whole thing was a very instructive exercise.

The Brothers Karamazov became Fyodor Dostoyevsky's last novel. It was based on notes he had been scribbling down for a long time, starting in 1869. Ten years later he began to outline the murder story, but it was not until the end of 1878 that he became seriously concentrated on the writing of the novel, probably in partly to alleviate himself from the deep depression that had hit him when his three-year-old son Alyosha died in May of that year, apparently as a result of the epilepsy he had inherited from his father. The year before, Dostoevsky had been diagnosed with pulmonary emphysema and his epileptic seizures had become increasingly frequent. His writing of The Brothers Karamazov turned into a long and difficult process, sometimes he wrote large passages himself, sometimes he dictated to his wife Anna, who also corrected, rewrote and edited large sections. Surviving manuscripts testify to how Dostoevsky struggled to structure his material.

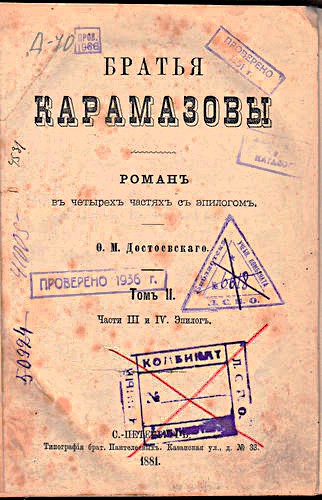

The Brothers Karamazov was serialized in the journal The Russian Herald. After the journal had announced it would publish a new major novel by Dostoevsky, anticipation of the reading audience was great, especially after a first instalment had been published in January 1879. However, the delays between each published episode increased over time, and so did the anticipation. In December 1879, Dostoevsky found himself compelled to ask the journal’s publisher, Michael Katkov, to publish the following notice.

This letter is a matter of my conscience. Let any accusations regarding the unfinished novel, if there are any, fall on me alone and not touch the editorial board of ”The Russian Herald,” which, if any accuser could reproach them in this case, it would only be for their extraordinary delicacy towards me as a writer and their constant patient indulgence towards my weakened health.

The last instalment of The Brothers Karamazov was published in November 1880, Dostoevsky died less than four months later.

Dostoevsky's grief over his deceased son came to characterize a large part of The Brothers Karamazov. To alleviate his grief, he had sought refuge in the Optina Monastery, famous as the centre for the Russian Orthodox faith in staretsy. Father Zosima, who is an important figure at the beginning of novel, was considered to be a starets, and the reader understands that it was a controversial concept that was far from being embraced by all Russian Orthodox believers. A starets is an elder who in some monasteries is revered as a spiritual advisor and teacher. Several of these staretsy were in Dostoevsky’s time considered to be faith healers and believed to have received their charisma and wisdom from God, a gift for their sacrificial lives and strict asceticism. Dostoevsky placed his young hero Alyosha in a monastery, as a close disciple of an elderly starets and gave him the same name as his deceased son, endowing him with such qualities that he admired and wished for himself.

During the course of the novel, Dostoevsky lets the pious Alyosha leave the monastery at the request of the dying elder Zosima, but Alyosha remains the saintly figure he was at the beginning – an admired, even beloved, confidant for the various characters.

After his experiences in the Optina Monastery and deeply moved by the death of his son, Dostoevsky wanted to change the entire structure of the novel so that it primarily reflected children's lives, their innocence and exposure to evil, accordingly he began to sketch a story that that placed children at its centre, though he changed his plans. Nevertheless, there is a great deal of naivety preserved in Alyosha's character and Dostoevsky makes him an admired friend and mentor for a group of children gathered around a previously bullied, but sensitive and lovable little boy. As we shall see, Dostoevsky also puts the suffering of children at the centre of his doubts about God’s omnipotence and mercifulness.

The final scenes in The Brothers Karamazov, when the boys gather around the dying, unusually kind-hearted Ilya, reminds me of Mark Donskoy’s film Maxin Gorky’s Childhood from 1938. I remember how moved I was when I saw it on TV sometime in my childhood. What stayed with me was the paralyzed little boy Alexei, who in a good-natured and positive manner befriends the twelve-year-old Maxim. Alexei collects insects in small boxes and pretends them to be different people around him. Like Dostoevsky’s terminally ill Ilya, little Alexei has gathered a group of helpful boys around him. He dreams of getting out into the “open fields” and in the end the movie, the little gang of compassionate boys pull the overjoyed Alexi, sitting in a carriage, out into the flowering expanses, where they all say goodbye to Maxim, who on his own is setting out into the world.

It has been a long time since I read Gorky’s My Childhood. I remember it as a rather sad read, but I don't recall any paralyzed boy and don’t think the book ended like in the film. Perhaps the touching story was an addition by Mark Donskoy, possibly inspired by The Brothers Karamazov in which Alyosha gives a beautiful speech to the nice little boys after Ilya's death, explaining that they when they all go out into the world and face their different fates, they will never forget the close-knit community they created around the sick Ilya and how it welded them together. Kindness is more beautiful and stronger than cruelty and evil. A lesson that Alyosha knows will follow the boys throughout their lives. I feel like I now have to read Gorky's My Childhood once again find out if the touching story about Alexei is really there.

I am far from the only one who has been captivated by Dostoevsky’s writing. Several writers have had transformative experiences through their encounter with the Russian titan. Some of them seem to have engaged in close combat with him. For example, Hemingway who often imagined his writing to be some kind of literary boxing match with prestigious and admired writers. He could for example write about Tolstoy.

I wouldn’t fight Dr. Tolstoi in a 20-round bout because I know he would knock my ears off. The Dr. had terrific wind and could go on forever and then some more. But I would take him on for six and he would never hit me and [I] would knock the shit out of him and maybe knock him out. He is easy to hit. But boy can he hit. If I live to 60 I can beat him (MAYBE).

Hemingway was convinced that he would beat other of his favourite authors, like Turgenev, Maupassant and Stendhal, but he seems to have hesitated to take up a fight with Dostoevsky. Perhaps because he was unsure about his technique. In A Movable Feast he writes about his relationship with Dostoevsky:

I've been wondering about Dostoyevsky. How can a man write so badly, so unbelievably badly, and make you feel so deeply?

Some years ago, I was an avid follower of the TV series Lost. I perceived the strange island on which the abandoned plane passengers had ended up as a kind of Purgatory where they after death (?) were tested to find whether they were worthy of continuing to live on within another existence. Lost became to me some kind of equivalent to Dostoevsky's world, a hellish place for purification and reflection. I was surprised when two of the main characters, John Locke (with the same name as a deeply Christian philosopher) and Jack Shephard, were confronted with each other towards the end. Locke is reluctant to leave the island and wants to teach the group of survivors to “trust” it and explore its mysteries, while Jack wants to get away from it and, if not possible, make sure that everyone is safe and able to stay alive. Suddenly Locke gives Jack The Brothers Karamazov with the words:

Did you know Hemingway was jealous of Dostoyevsky? He wanted to be the world’s greatest writer but convinced himself that he could never get out from under Dostoyevsky's shadow.

I understood this as if Locke meant that Jack as a man of “man of action” could not admit that through all his struggle to free himself from his fate, perhaps “God’s will”, he could not possibly reconcile himself with the great mysteries of existence. But like most things in Lost, this scene was ambiguous and difficult to interpret, and that was probably what attracted me to this TV series, which in all its strangeness became a global success.

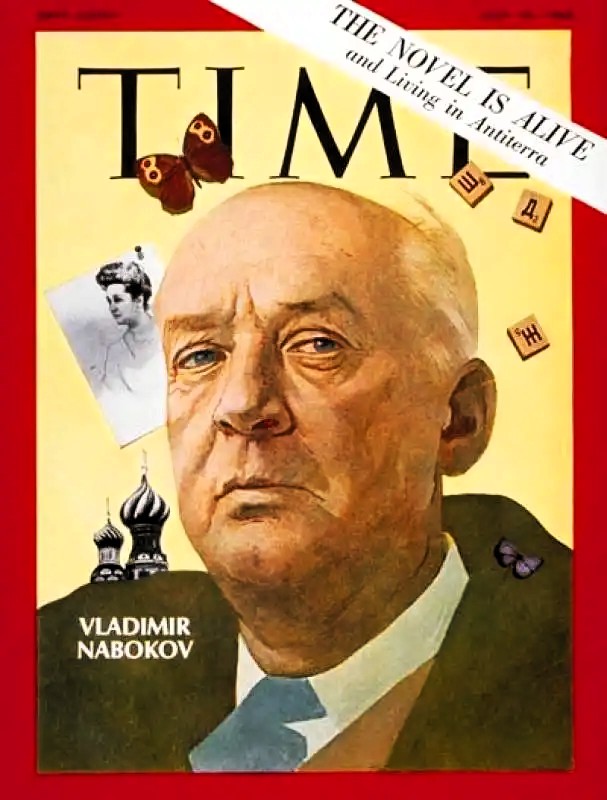

Another, usually brilliant, writer who, like Hemingway, could fall into self-made traps of self-overestimation, and thus occasionally hit rock bottom, was Vladimir Nabokov. He nourished great objections to Dostoevsky and, unlike Hemingway, did not seem to have any admiration whatsoever for him.

Nabokov seems to have read Dostoevsky like the Devil reads the Bible and was annoyed that his novels were populated by “neurotics and lunatics”, that Dostoevsky’s characters did not develop, that they from beginning to end remained the same. I wonder. Does Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert in his masterpiece Lolita develop much? In The Brothers Karamazov, even Alyosha, who in my opinion is insufferably good-natured and naively pious, changes. In all his angelic piety he is nevertheless tormented by remorse and perhaps even hides some less sympathetic traits.

Nabokov found Dostoevsky’s novels garnished with surprise elements and unexpected developments, but ... on rereading they revealed themselves as “glorified cliché”, cooked up according to the same well-tried recipe, namely a presentation of a multitude of individual worlds, which are mixed together and served under the name of “objective realism”. Well, Nabokov is quite resourceful and witty, but I have difficulties digesting his superior attitude. Nabokov’s final judgement is exceedingly harsh:

Dostoyevsky is not a great writer, but a rather mediocre one - with flashes of excellent humour, but, alas, with wastelands of literary platitudes in between.

Worst of all is his pathetic writing style:

in all of Dostoyevsky’s novels there is a rush and tumble of words with endless repetitions, mutterings aside, a verbal overflow which shocks the reader after, say, Lermontov's transparent and beautifully poised prose.

I see it differently, it is this kaleidoscopic, often highly vivid “unwieldiness” that makes Dostoevsky’s novels alive, which brings them close to the reader. Nabokov’s disparaging views have been contradicted by a number of literary greats, none less than Jorge Lous Borges, who with his wry and witty acumen wrote:

In the preface to an anthology of Russian literature, Vladimir Nabokov stated that he had not found a single page of Dostoevsky worthy of inclusion. This ought to mean that Dostoevsky should not be judged by each page but rather by the total of all the pages that comprise the book.

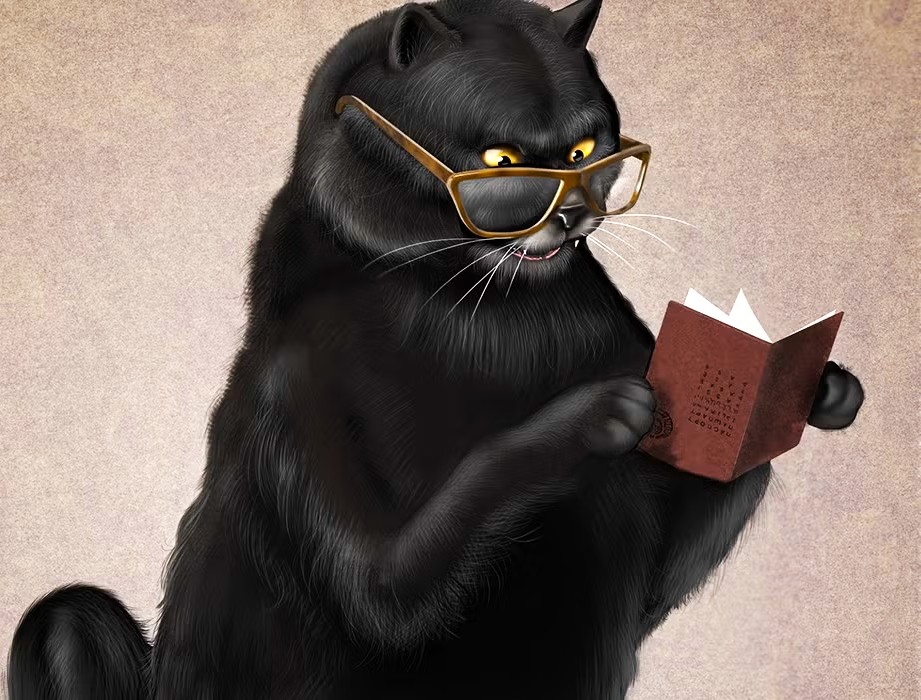

Long before that, the demonic cat Behemoth in Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita had angrily snapped at a “knowing citizen” who had stated that Dostoevsky was dead. “I protest!” Behemoth hissed heatedly. “Dostoevsky is immortal!”

There is a long list of great writers who have defended Dostoevsky, stating how much he meant to them. Some examples:

Arthur Power, an artist best known for befriending James Joyce (he described it as getting to know barbed wire) and conducting numerous interviews with the author, mentioned, among other things, that Joyce had told him that

The Brothers Karamazov made a deep impression on me. He created some unforgettable scenes. Madness you may call it, but therein may be the secret of his genius. I prefer the word exaltation, exaltation which can merge into madness, perhaps. In fact, all great men have had that vein in them; it was the source of their greatness; the reasonable man achieves nothing.

Virginia Woolf had also been swept away by Dostoevsky's violent, psychological whirlwinds:

Dostojevskijs romaner är en sjudande malström, snurrande sandstormar, gejsrar som fräser och kokar, suger in oss. De består enbart av själslig substans. Mot vår vilja dras vi in, virvlas runt, förblindas, kvävs och samtidigt fylls vi av en yr hänförelse. Utanför Shakespeare finns ingen mer spännande läsning.

Som så många andra fann amerikanen James Baldwin det lätt att identifiera sig med Dostojevskijs plågade gestalter och fann lugn i en sådan identifikation:

Du läser något som du trott enbart hänt dig, men så upptäcker du att det hände Dostojevskij för 100 år sedan. Detta blir till en mycket stor befrielse för den lidande, kämpande människan, som ständigt inbillar sig att hon är ensam. Det är därför konst är så viktigt. Konst skulle inte vara angeläget om livet inte vore viktigt, och livet är viktigt.

Like so many others, the American James Baldwin found it easy to identify with Dostoevsky’s tormented characters and found peace in such identification:

You read something which you thought only happened to you, and you discover that it happened 100 years ago to Dostoyevsky. This is a very great liberation for the suffering, struggling person, who always thinks that he is alone. This is why art is important. Art would not be important if life were not important, and life is important.

Hemingway’s great rival on the American Parnassus, William Faulkner, was also an avid reader of Russian classics. He reread The Brothers Karamazov almost every year. As far as I know, Faulkner and Hemingway did not enter into any literary melee, other than Faulkner found Hemingway to be linguistically limited, while Hemingway considered-% Faulkner’s style to be excessively pompous.

In literary circles, there is sometimes a dispute about who of the two Nobel Prize winners is the best writer. It reminds me of old men quarrelling about who to prefer – Rolling Stones or Beatles. When it comes to Faulkner and Hemingway, they two very different stylist, though I cannot help but lean towards Faulkner as the one that interests me the most. The style of his As I Lay Dying captivated me the first time I read it, and I found Absalom, Absalom! To be as intricate as The Brothers Karamazov.

Despite their differences, the trio of Faulkner, McCullers and O’Connor are part of the genre of Southern Gothic-Grotesque. All of them are certainly great and strange writers. Their strangeness and attraction can probably be considered by the fact that, like Dostoevsky, they were nonconformists and wrote from their outsider status. The two ladies found themselves outside the framework of the Southern idea of what women should be like and Faulkner did not behave as befitted a Southern gentleman.

Carson McCullers, who made her debut at barely 23 years old with the fascinating The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, has generally been called eccentric. Which is hardly an exaggeration when it comes to describing this hypersensitive and at the same time tough and earless woman. About Faulkner and Hemingway she wrote:

I have more to say than Hemingway, and God knows, I say it better than Faulkner.

Like Faulkner and O'Connor, McCullers could perceive the similarities between the best Southern writers and an author like Dostoevsky. She wrote that Southern writers were deeply indebted to the Russians, that their Gothic strain was like the one of Dostoevsky, where there were no ghouls and ghosts, instead it was the human soul that was haunted and people were the demons.

It is in their approach to life and suffering that the Southerners are so indebted to the Russians. The technique briefly is this: a bold and outwardly callous juxtaposition of the tragic with the humorous, the immense with the trivial, the sacred with the bawdy, the whole soul of man with a materialistic detail.

McCullers described how she first became acquainted with Dostoevsky and how it changed her view of life:

The books of Dostoevsky – The Brothers Karamazov, Crime and Punishment, and The Idiot – opened the door to an immense and marvellous new world. For years I had seen these books on the shelves of the public library, but on examining them I had been so put off by the indigestible names and the small print. So, when at last I read Dostoevsky, it was a shock that I shall never forget – and the same amazement takes hold of me whenever I read these books today, a sense of wonder that cannot be jaded by familiarity.

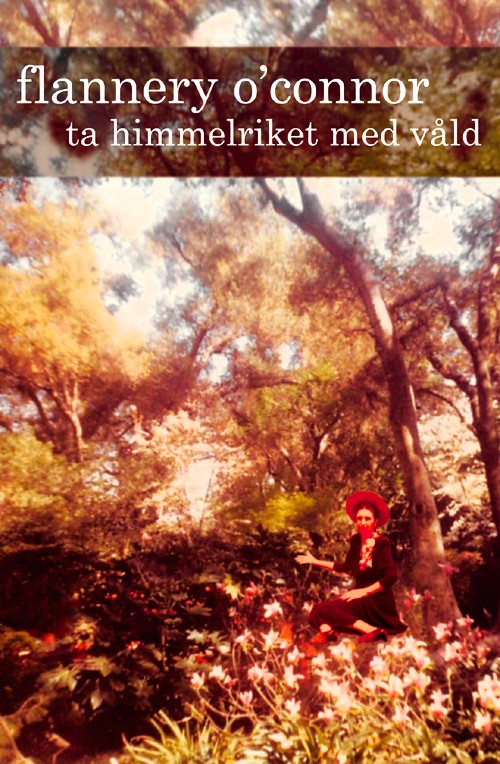

The other lady of the Southern Gothic trio, the Catholic author Flannery O’Connor, might perhaps be considered to an even greater extent than Faulkner and McCullers as an American equivalent of Dostoevsky, not least through her strongly expressed Christian faith. However, it is certainly not some Sunday school peace that rests over her brutally primitive South.

O’Connor expressed her goal as describing how God’s grace could work within a world dominated by the Devil. As with Dostoevsky, her characters are generally degraded, confused and love-starved losers in a world that could just as easily be Hell on Earth, filled as it is with lurking demons in human form, drenched in drugs, alcohol, brutal crime, corruption, racism and prostitution. All portrayed by an author who declared that:

To ensure our sense of mystery, we need a sense of evil which sees the devil as a real spirit who must be made to name himself, and not simply to name himself as vague evil, but to name himself with his specific personality for every occasion. Literature, like virtue, does not thrive in an atmosphere where the devil is not recognized as existing both in himself and as a dramatic necessity for the writer.

In O’Connor’s short stories and novels, it often seems, as the case with Dostoevsky, that the Devil’s (fate, injustice, violence, necessity, whatever form Satan might take) ruthlessly brutal attacks on doubting, vulnerable individuals plunge them into mad confusion, only to finally (in some cases) prepare them for an unconditional surrender to the mystery of faith and divine grace.

Take, for example, O’Connor’s novel The Violent Bear It Away, in which the young Tarwater is attacked by the Devil in both his inner and outer manifestations. This happens in the form of an inner voice, a “stranger” who gradually becomes a “friend.” However, this “inner stranger” is of course none other than the Mean Tempter himself, Satan, who almost completely obscures another inner “friend” – Christ. The novel’s outer demons are con artists and perverted rapists, who with the help of the inner voice lure Tarwater into despair and victimize him. Like the devils we soon will encounter in in the company of Dostoevsky and Thomas Mann, Tarwater's inner Satan denies his own existence and claims to be a reflection of his own overheated imagination. However, it is, like everything the Devil tells us, a lie. All this may seem to be taken from a Christian edification book, or a pious sermon. Nevertheless, that is not how Flannery O'Connor writes. Her purpose is well hidden, the pointers absent. Her world is cruel and harsh. Her merciless narrative grabs the reader and keeps her/him in an iron grip.

What the other great Southern writer, William Faulkner, most appreciated in Dostoevsky was his ability to portray the subconscious, how contradictory human emotions really are. He considered The Brothers Karamazov to be his most significant literary inspiration, alongside Shakespeare and the Bible. According to Faulkner, American literature had not been able to achieve anything nearly as impressive as The Brothers Karamazov. In his Nobel Prize lecture, Faulkner mentioned what he considered to be the goal that he and Dostoevsky were moving towards, namely to describe

the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself which alone can make good writing because only that is worth writing about, worth the agony and the sweat.

The antihero in Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! Sutpen, is a tragic and rather absurd Dostoevsky character, who struggles to elevate himself and win the respect of those around him. Despite his obvious strength and determined personality, Sutpen cannot escape what he detests within himself and he fails miserably in his life project. Sutpen’s violent personality and overwhelming vanity, his longing for grandeur and redemption, become his defeat. Like the protagonist in Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underworld, Sutpen pities himself in a mixture of pride and self-loathing: “I am a sick man... I am a bad man. An unattractive man.” Like Dostoevsky's antihero, Sutpen seems to accept and even in a way find satisfaction in the rejection of the surrounding society. These embittered, lonely characters allow themselves to be consumed by chronic negativity, self-loathing and ill will towards everything and everyone.

There is a demonic undercurrent in The Brothers Karamazov. Several commentators consider the novel to be a deeply Christian fable with the elder Zosimov and his faithful disciple Alyosha as bearers of its message – it is within the folds of the Russian Orthodox Church that we find peace and meaning in our lives.

Just as one considers Alyosha to be the hero of the novel, one can also see his tormented brother Ivan as its central figure. It is Ivan who carries and advances Dostoevsky’s doubts about divine justice and the presence of God. Ivan tells his religious brother about his idea for a poem/play about the Grand Inquisitor’s meeting with Jesus. Alyosha listens intently, without making any comments.

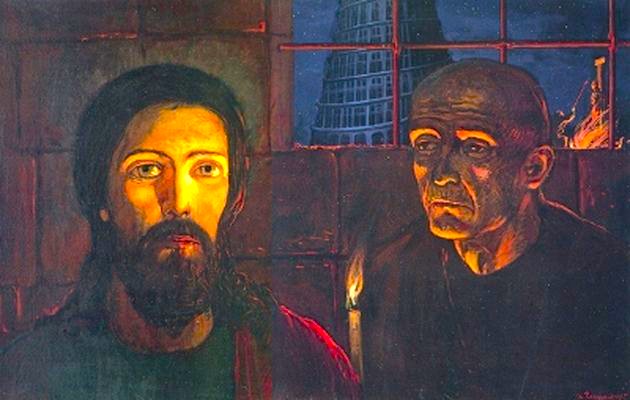

In broad terms, Ivan’s story deals with how Jesus returned to earth, more specifically to Seville during a time when heresy bonfires lighted up the town squares. The Grand Inquisitor was at the height of his power. Jesus performs miracles and gathers people around him, which causes the Inquisition’s henchmen to react and imprison him. At night, the Grand Inquisitor visits Jesus in his cell. He has no doubts at all about whom he is encountering and explains why it is the Church’s intention to burn him at the stake as a heretic the following day. During the Grand Inquisitor’s tirade, Jesus remains silent.

The church potentate considers the return of Jesus to be a serious threat to the entire empire that the Church has created for the good of humanity. The Church is now leading humanity in the right direction, towards a final unification of the human race under one power, one state, which will provide every citizen with her/his daily bread, control and soften the conscience of humanity and once and for all establish principles that will unite and guide all of humanity.

Jesus limited his message to a small group of chosen ones, while the Church has improved on his efforts by speaking to the entire humanity and rule the world in the name of God. The Church no longer needs Jesus; he has become a nuisance.

By proclaiming the freedom of choice to people, Jesus created unnecessary anxiety. People are safer if they do not have to choose and instead allow themselves to be ruled by others. Through his teaching about the free choice Jesus excluded the majority of humanity from redemption and condemned most of us to suffering. Salvation and unity are provided through the Church Organization, which has shouldered the burden of freedom and thereby given individuals peace and security. The Inquisitor believes that under him and his ilk, all humanity will live and die in blissful ignorance. Even if life and the leadership of the Church should ultimately lead to death and destruction, the majority of the humans will be happy on their journey towards a future goal:

We will make them work, but in the hours free from labour we will arrange their lives like a children’s game, with children’s songs, choruses, and innocent dancing. Oh, we will allow them to sin, too; they are weak and powerless, and they will love us like children for allowing them to sin. We will tell them that every sin will be redeemed if it is committed with our permission; and that we allow them to sin because we love them, and as for the punishment for these sins, very well, we take it upon ourselves. And we will take it upon ourselves, and they will adore us as benefactors, who have borne their sins before God. And they will have no secrets from us. We will allow or forbid them to live with their wives and mistresses, to have or not to have children – all depending on their obedience – and they will submit to us gladly and joyfully. The most tormenting secrets of their conscience – all, all they will bring to us, and we will decide all things, and they will joyfully believe our decision, because it will deliver them from their great care and their present terrible torments of personal and free decision. And everyone will be happy, all the millions of creatures, except for the hundred thousand of those who govern them. For only we, we who keep the mystery, only we shall be unhappy. There will be thousands of millions of happy babes, and a hundred thousand sufferers who have taken upon themselves the curse of the knowledge of good and evil. Peacefully they will die, peacefully they will expire in your name, and beyond the grave they will find only death. But we will keep the secret, and for their own happiness we will entice them with a heavenly and eternal reward.

The Inquisitor recalls how Christ rejected the Devil’s temptations and stated that man cannot live by bread alone. But it was a fatal mistake:

Feed men, and then ask of them virtue! That's what they'll write on the banner they'll raise against Thee and with which they will destroy Thy temple.

Even when the Grand Inquisitor has finished his long monologue, Jesus remains silent. He rises slowly and then kisses the Inquisitor on his “bloodless, aged lips.” The Inquisitor releases Christ but warns him never to return. Jesus, still silent, goes out into the “dark alleys of the city.” Ivan concluded his story with the words: “The kiss burns in his heart, but the old man adheres to his idea.”

Since he intends to leave the city, Ivan had like some kind of farewell told the story to his little brother. He notices that he has made him terribly upset, especially through his claimed that if God is dead, everything is permitted. Ivan smiles towards his pious brother:

I thought that going away from here I have you at least, but now I see that there is no place for me even in your heart, my dear hermit. The formula, ”all is lawful,” I won’t renounce – will you renounce me for that, yes?

Alyosha, who has risen from his chair, now went up to Ivan and kissed him right on the mouth, which made Ivan exclaim:” “That’s plagiarism. You stole that from my poem. Thank you though.”

Perhaps Ivan sensed that Alyosha, like so many others around him, not least his beloved but theatrical Katérina, was playing a game. Alyosha’s piety was perhaps also a hard-won conviction, a fragile defence against all the evil and moral decay he found himself surrounded by. For a man like Alyosha, his brother’s talk about the death of God must have been a terrible threat to his faith, which was perhaps not as rock-solid as Dostoevsky would like us to believe.

The idea of the death of God was not new, but Dostoevsky’s Ivan took it to its extreme and makes him an advocate of the nihilism he feared so much, namely that if God is dead and everything is permitted, then this indicates that life is meaningless, that moral values are groundless and knowledge is impossible. It was in these border areas that Friedrich Nietzsche moved. Two years after Dostoevsky's death in 1880, he described in his The Joyous Science how “a madman” proclaimed

Where is God?’ he cried; ‘I’ll tell you! We have killed him – you and I! We are all his murderers. But how did we do this? How were we able to drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? Where is it moving to now? Where are we moving to? Away from all suns? Are we not continually falling? And backwards, sidewards, forwards, in all directions? Is there still an up and a down? Aren’t we straying as though through an infinite nothing? Isn’t empty space breathing at us? Hasn’t it got colder? Isn’t night and more night coming again and again? Don’t lanterns have to be lit in the morning? Do we still hear nothing of the noise of the grave-diggers who are burying God? Do we still smell nothing of the divine decomposition? – Gods, too, decompose! God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him! How can we console ourselves, the murderers of all murderers! The holiest and the mightiest thing the world has ever possessed has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood from us? With what water could we clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what holy games will we have to invent for ourselves? Is the magnitude of this deed not too great for us? Do we not ourselves have to become gods merely to appear worthy of it? There was never a greater deed – and whoever is born after us will on account of this deed belong to a higher history than all history up to now!’

Nietzsche stated that belief in God had become obsolete, as had everything based on this belief. Everything that developed from and had been supported by the belief in an omnipotent God was now doomed to disappear. The whole of European morality would collapse. Humans now stood alone in the universe and had to shoulder their responsibility for all existence, for that which they had believed to be God’s creation. A terribly difficult task that demanded more than what an ordinary person could be capable of. Someone stronger, someone more than an ordinary person, a very strong being was now needed – the Superman. A dictator? A fascist, an SS officer? I don't think so. Nietzsche was far from being a thinker who moved along some pre-arranged, conventional paths. Despite serious blemishes among his ideas, I am inclined to believe that Nietzsche harboured so much compassion that would make such assumptions and interpretations of his teachings impossible. After all, he was “human, all too human.”

Nietzsche also grappled with the reality of evil and considered that it was unfortunately an integral part of human existence, characterized as it is by suffering and despair. But we must not fall for any fantasies that take away the responsibility for evil from people.

According to Nietzsche, the Devil is a vulgar concept that we have as little use of as we have of God. However, as the artist he actually was, Nietzsche could not help but speculate about the nature of this imaginary creature. He wrote that if God represented authority, oppression, imposed order and cold logic, the Devil stood for creative capacities and potentials like love, emotions and joy. Thereby the Devil had become “wisdom’s most ancient friend”, who “keeps us as far away as possible from a God who is so harmful to us”. Here the contradiction between Apollo and Dionysus, as Nietzsche highlighted in his The Birth of Tragedy, probably still haunted him.

The first time Nietzsche was confronted with Dostoevsky’s writings was when he in Nice bought and read Notes from Underground. He was enthralled by its depiction of the miserable existence of a man living without any belief in God. He considered his find of the book to be "among the most beautiful strokes of fortune in my life.” Soon thereafter, Nietzsche had read several of Dostoevsky’s books and concluded that the Russian author was the only psychologist who could really teach him something new. The introduction to Dostoevsky’s existentialism, the metaphysical suffering that afflicts so many of his characters, made Nietzsche believe that “excessive consciousness” was simply a form of illness.

The Brothers Karamazov was translated into French in 1888 and an anonymous translation into German had appeared as early as 1884, but it does not seem as if Nietzsche had been able to read any of them. By January 1889, Nietzsche had irreversibly entered his paralyzing mental dead. However, if he does not explicitly mention Ivan’s statement that "if God is dead, everything is permitted", this does not indicate that Nietzsche, with his great interest in Dostoevsky, was not familiar with the expression. In a letter to his friend Peter Gast, Nietzsche mentions a German theatre production of The Brothers Karamazov and it is possible that he attended it.

Like Dostoevsky and O'Connor, Nietzsche did, despite his atheism, consider suffering as a form of purification, a path to self-realization. It could help us to defeat evil and despair, forcing them under our control, our will:

To those human beings who are of any concern to me I wish suffering, desolation, sickness, ill-treatment, indignities—I wish that they should not remain unfamiliar with profound self-contempt, the torture of self-mistrust, the wretchedness of the vanquished: I have no pity for them, because I wish them the only thing that can prove today whether one is worth anything or not—that one endures.

This ascertainment was found among the many notes and drafts that Nietzsche’s eventually Nazi-tainted sister, Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, and his good friend Peter Gast collected after his death and published as The Will to Power. Accordingly, the general opinion about this book has been that several of the views exposed in it can to be considered as entirely reliable. However, in recent years it has been found that the sister's clumsy editing, additions and deletions, were not as bad and extensive as it previously had been feared and has been translated into several languages and republished.

In any case, Nietzsche often wrote about the harsh ordeal it meant to go your own way, living in a world without God, where you only have yourself to blame. In The Will to Power, Dostoevsky's tormented characters occasionally appear and at one point Nietzsche wrote:

To represent terrible and questionable things is, in and of itself, an expression of the artist’s instinctive desire for power and glory. There is no such thing as pessimistic art. Art affirms. Job affirms. But Zola? The Goncourt brothers? The things they show are ugly, but the fact that they show them stems from their delight in ugliness. There is no avoiding it” You deceive yourselves if you think otherwise. How liberating Dostoevsky is!

Ivan's denial of God, his nihilism, cost him dearly. He did not get the woman he desired, while a guilty conscience consumed him. What if it was his constant assertion that “if God were dead then everything was permitted” that had inspired the murder of his father? Ivan, like his passionate brother Dimitri, began to lose his grip on reality and, like O'Connor's Tarwater, he felt the suffocating presence of the Devil, both within and without himself. One night, Satan appeared in front of him, very tangible, sitting in a chair:

a person of some sort, or more accurately speaking, a Russian gentleman of a particular kind, no longer young, qui faisait la cinquantaine, as the French say, with rather long, still thick, dark hair, slightly streaked with grey and a small pointed beard. He was wearing a brownish reefer jacket, rather shabby, evidently made by a good tailor though, and of a fashion at least three years old, that had been discarded by smart and well-to-do people for the last two years. His linen and his long scarf-like neck-tie were all such as are worn by people who aim at being stylish, but on closer inspection his linen was not overclean and his wide scarf was very threadbare. The visitor's check trousers were of excellent cut, but were too light in colour and too tight for the present fashion. His soft fluffy white hat was out of keeping with the season. In brief there was every appearance of gentility on straitened means. It looked as though the gentleman belonged to that class of idle landowners who used to flourish in the times of serfdom.

The cynical Devil, who changes form during the night, often in accordance with his statements, torments Ivan by reminding him of his failures, his feelings of guilt for ill-considered statements and ideas he spread around himself and thus maybe inducing others to commit deplorable acts. The Devil makes it clear to Ivan that Hell is among us and manifests itself through suffering caused by not being able to love, of not being loved, and instead indulge in a knowledge freed from love and compassion. Ivan shouts at the mocking Devil: ”You are an incarnation of me, but only one side of me!”

Deep down, Ivan is not a cynic, and his torments come from the realization that he actually likes people and even loves some of them. However, his bad conscience that gnaws at him. Like Tarwater’s Satan, Ivan’s Devil has already proven himself to be a master of deception and lies, so he has no difficulty whatsoever in his attempts to convince Ivan that he is only a figment of his imagination and that Ivan is actually becoming mad. Nevertheless, neither Ivan nor the reader are completely convinced of this – perhaps the Devil actually exists.

In any case, he appears several years later when the composer Adrian Leverkühn meets him one night in Palestrina. Like when he visited Ivan, the Devil is fairly modern, but shabbily, dressed. And as when he haunted Ivan, the Devil does from time-to-time change appearance, but to begin with Thomas Mann, author of Doctor Faustus, describes him as a more brutal type,

rather spindly, not nearly so tall as Sch., smaller even than I. A sports cap over one ear, on the other side reddish hair standing up from the temple; reddish lashes and pink eyes, a cheesy face, a drooping nose with wry tip. Over diagonal-striped tricot shirt a chequer jacket, sleeves too short, with sausage-fingers coming too far out, breeches indecently tight, worn-down yellow shoes. An ugly customer, a bully, a stnzzi , a rough. And with an actor’s voice and eloquence.

I don't really know what a stnzzi is, and even though I now have lived in Italy for several years I cannot recall ever hearing the word. Maybe, maybe, it has to do with sto zitto, "I'm silent, I don't care," meaning that the Devil is an insensitive type.

It was probably no coincidence that Adrian Leverkühn met the Devil in Palestrina just before the outbreak of the World War I. It was in this town that the composer Giovanni da Palestrina was born exactly five hundred years ago (the anniversary is this year celebrated with concerts and exhibitions). Palestrina is considered to be one of the greatest masters of polyphonic choral works ever, and for the brilliant composer Leverkühn, he symbolised the European high culture that will soon would be threatened with extinction by the War.

The place may also have something to do with Thomas Mann’s own life story. In 1953, the then 77-year-old Mann returned to Italy for the last time and met at the Hotel Excelsior in Rome with a Munich-born artist, Fabius von Gugel, who was living in Rome. Mann told him that in his youth he had spent a few summer weeks in Palestrina. One clammy afternoon he had been sitting in the stone hall beneath Palestrina’s ancient palace when a stranger dressed in black had appeared, looked intently at him, without uttering a single word. Mann had been overcome by a wave of icy terror, convinced that the apparition was the Devil himself. Without Mann having been able to address him, the apparition disappeared as suddenly as it had emerged. The experience had for all time been etched into Mann's memory. We might suspect that Mann, like Dostoevsky, with his vivid imagination easily could evoke such visions from his inner terrors and bad conscience. Like Dostoevsky, Thomas Mann was a passionate man, who at times suffered from depression, repressed desires, and fear, feelings that he transformed into literature.

The spirits of Nietzsche and Dostoevsky haunted much of what Thomas Mann wrote. He was fascinated by the morbid madness of these geniuses and was more fascinated by their dark sides than by their philosophy. In an essay he wrote Dostoevsky, Mann stated:

above all it depends on who is diseased, who is mad, who is epileptic, or paralytic: an average dull-witted man, in whose illness any intellectual or cultural aspect is non-existent; or a Nietzsche or Dostoyevsky. In their case something comes out in illness that is more important and conducive to life and growth than any medical guaranteed health or sanity.... In other words: certain conquests made by the soul and the mind are impossible without disease, madness, crime of the spirit.

Thomas Mann, the atheist, doesn't care much about Dostoevsky's Christian message, it is the misery and spiritual misery he focuses on. According to him, Dostoevsky was:

An author whose Christian sympathy is ordinarily devoted to human misery, sin, vice, the depths of lust and crime, rather than to nobility of body and soul.

In Doctor Faustus there are plenty of internal and external demons, among the latter one might list the art historian Helmut Insitoris, the stuttering music teacher Mr. Kretschmer (who made me think of my own demonic violin teacher Kopsch), the charming translator Martin Schildknapp, the red-haired doctor Dr. Zimbalist, Saul Fitelberg who seems to have been created with Mephistopheles as a model, and above all the philosopher Dr. Eberhard Schleppfuss, who to some extent, like Ivan in The Brothers Karamazov, preaches a dangerous nihilism. Dr. Schleppfuss believes that God allows evil for the sake of free will. As in O’Connor’s stories, Dr. Schleppfuss believes that God’s goodness consists in His ability to create good out of evil and takes this as a defence for the presence of evil within His creation.

Dr. Serenus Zeitblom, the narrator of the novel (like Dostovsky in The Brothers Karamazov, Mann in Doctor Faustus makes use of a narrator between himself and the reader) believes that the theological apparatus of Christianity, like the demonic Nazism, constitutes a creepy escape from human realities and loving tenderness. Centuries of extraterrestrial speculation had transformed Jesus’ simple and straightforward teaching of love and compassion into a suffocating abuse of power. It was not for nothing that the soldiers of the Nazi army on their belt buckles wore the inscription Gott mit uns, God is with us.

It is in Palestrina that Adrian Leverkühn offers his soul to the Devil, on the condition that he should love no one, but instead devote his life to the perfection of his music. Like Dostoevsky’s demonic nihilists, Leverkühn, more or less consciously, spreads death and suffering around him. It is only through the compassionate and lovingly helpless anguish he feels when his little nephew Nepomuk succumbs to the unfathomable pain of a fatal illness that the Devil finally loses his grip on Leverkühn. Here too, Mann seems to have found a model in The Brothers Karamazov, in which the decommissioned captain Snigirov is almost indescribably tormented by the long-lasting death agony of his lovable son Ilya.

The underlying crime in The Brothers Karamazov is a parricide, and this was of course something that attracted Sigmund Freud, who delved into the book and dedicated a long essay to Dostoevsky. Something that once again convinces me that Freud should have received his Nobel Prize in literature and not in medicine. I have come to the conclusion that several of his insights and theories are undeniably intellectually stimulating, but hardly based on any sound, empirical science.

Freud admired Dostoyevsky’s ability to us an “unparalleled artistic intuition” while revealing the human mind’s attempts to hide its inner workings from itself. He considered The Brothers Karamazov as “the most magnificent novel ever written” and was of course fascinated by its Oedipal undertones. In 1928, Freud published an essay entitled Dostoevsky and Parricide in which he analyzed Dostoevsky’s neuroses and argued that the Russian writer’s epilepsy was not a “natural condition,” but rather a physical manifestation caused by Dostoevsky’s repressed feelings of guilt over his father’s death.

It can scarcely be owing to chance that three of the masterpieces of the literature of all time the “Oedipus Rex” of Sophocles, Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” and Dostoevsky’s “The Brothers Karamazov” should all deal with the same subject, parricide. In all three, moreover, the motive for deed, sexual rivalry for a women, is laid bare.

A view that is clarified in Freud’s analysis of The Brothers Karamazov. He considers it to be quite uninteresting who actually committed the patricide that the novel revolves around. A deep psychological consideration should instead take into account who emotionally desired and welcomed the incompetent father’s death. An aspect that Dostoevsky clearly emphasizes and he has the intellectual, but at that time deranged Ivan screaming in the courtroom:

Who doesn’t wish for his father’s death? … Everyone wants his father dead. Viper devours viper…

Even the righteous Alyosha is guilty of parricide. He buried himself in religious musings and thereby neglected the precarious situation of his own family. As a devoted Christian he is forced to bear the burden of the sins of others. It is this Christian view that eventually becomes Freud’s most vehement and, in fact, only criticism of Dostoevsky and his work. He states that the Russian author’s unconditional surrender to the Russian Orthodox Church squandered his opportunity

the chance of becoming a great teacher and liberator of humanity and made himself one with their jailors.

Franz Kafka had a great admiration for Dostoevsky and read him extensively. In 1913 he wrote a letter to Felice Brauer, “the most wonderful woman on this earth,” apparently to avoid a marriage she had hinted at, but also as an attempt to keep her as a close friend. It is one of the few occasions on which Kafka mentions Dostoevsky by name, although it is easy to discern the Russian influence in much of what he wrote:

Don't forget that of the four people whom I (without comparing myself to them in terms of creative power or literary importance) consider to be my true soul mates – Grillparzer, Dostoevsky, Kleist and Flaubert – only Dostoevsky got married and perhaps only Kleist drew the right conclusion when, due to external and internal compulsion, he shot himself at Wannsee.

Of these authors I was completely unfamiliar with Grillparzer, until a month or so ago when I began sketching on a blog about Medea, which I have not yet finished and the Austrian playwright’s play about her. I thought I could understand why Kafka wrote so appreciatively to Felice about that particular author. He is quite good, but I suspected that Kafka might have mentioned him in connection with his refusal to marry Felice. Grillparzer’s Medea drama depicts the mutual fascination and disgust that prevails between the passionate Medea and the fundamentally cowardly Jason, and how disgust, through Jason's betrayal, ultimately becomes the dominant force that causes Medea to murder their child in a vengeful rage.

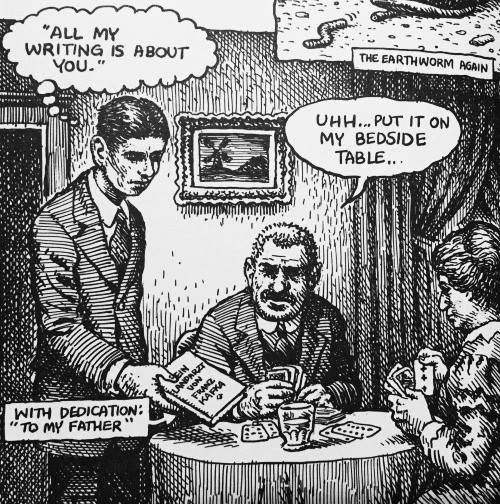

Of course, Kafka was shaken and touched by The Brothers Karamazov and not the least the despicable father figure Dostoevsky depicted. A vulgar and wretched man, hated and despised by his three sons. Kafka’s relationship with his own father was probably not as terribly hateful as that of the Karamazov Brothers. However, Kafka certainly suffered under his father’s shadow:

A true Kafka in strength, health, appetite, loudness of voice, eloquence, self-satisfaction, worldly dominance, endurance, presence of mind, knowledge of human nature, a certain way of doing things on a grand scale, of course also with all the defects and weaknesses that go with these advantages and into which your temperament and sometimes your hot temper drive you.

A 45-page letter that Kafka wrote to his father in 1919, which according to his friend Max Brod he wanted his mother to give to him, although she never did it, began with the words:

Dearest Father,

You asked me recently why I maintain that I am afraid of you. As usual, I was unable to think of any answer to your question, partly for the very reason that I am afraid of you, and partly because an explanation of the grounds for this fear would mean going into far more details than I could even approximately keep in mind while talking. And if I now try to give you an answer in writing, it will still be very incomplete.

The father did obviously not read his son’s letter to him and probably not his other work. Nothing that Kafka undertook aroused his father's appreciation or interest, and his writing was consequently met with indifference or reluctance. Each new book was by the constantly card playing father, with the words: "Put it on my bedside table." Yet these books concerned his father more than any other: “My writing was all about you; all I did there, after all, was to bemoan what I could not bemoan upon your breast.”

By Kafka the boundaries between an outer and an inner world are erased to an even greater extent than they were in the works of O’Connor and Dostoevsky. Reality is fragmented and threatens to collapse. His characters belong to the same sphere as the often elusive and sometimes inhuman figures that threaten us within a world we feel that we cannot escape from. Kafka expresses the tragedy of everyday existence and points to the absurd paradox that even if we sometimes can perceive the strangeness of life, we accept it with a thoughtless simplicity.

Like dreams, Kafka’s stories are self-sufficient, they follow their own consistent logic and the reader is forced to accept it. This nightmarish mood is supported and reinforced by Karka’s precise and formal use of language, which in the midst of all its seriousness is not devoid of subtle humour and wit.

In this, Kafka is not entirely unlike Dostoevsky. In a preface to Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway, Elaine Showalter (whose book Sexual Anarchy, I should mention, made a great impression on me) pointed out that in several pioneering, modernist writers, such as Joyce and Woolf, the subconscious emerges and colours their narrative. As with Dostoevsky, dreams and memories become as important as actions and thoughts. Instead of the fixed perspective of the omniscient narrator, Dostoevsky broke up the structure of the narrative. In his footsteps, writers, like the Cubist - and Futurist painters, could break down and transform the visual reality. In Dostoevsky's case, the narrative style became an integral part of the plot, giving it a dimension separate from reality. A method that was later refined by writers such as Kafka, Joyce, Woolf and Faulkner, especially in the latter, who in his Absalom, Absalom! allowed the narration to come to the forefront in such a manner that the reader becomes unsure of who is telling what, while the different points of view make the story itself multifaceted and uncertain.

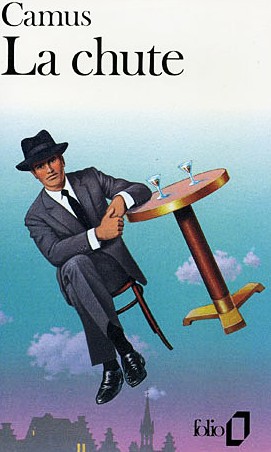

Someone who delved deep into Kafka’s writings was Albert Camus, who stated that the absurd effect that Kafka creates does not come from some vague fantasy but is rather “an excess of logic”. According to Camus, a visit to Kafka’s universe was like “the painful luxury of fishing in a bathtub, knowing that nothing comes out of it.” Truth and illusion are by Kafka mixed together in such a way that they are deprived of their anchorage in reality, while a mirror world is created. “Truth is constantly on the way of losing its mask and reveal itself as illusion, while illusion can pass into truth.”

While Dostoevsky’s novels appear paradoxical and contradictory, they are nevertheless populated by individuals, though more in the shape of “automatons" than “real people”, but that does not hinder the reader identifying her/himself with them, since they embody

perpetual oscillations between the natural and the extraordinary, the individual and the universal, the tragic and the everyday, the absurd and the logical”, and it is these eternal paradoxes that provide his work with resonance and meaning.

In all their abstraction, Kafka's heroes are like “all others”. They resemble us, while the world they inhabit is unmistakably similar to the reader’s own, with its obscure hierarchy of bureaucracy, in all its everyday absurdity, it remains unbearably familiar.

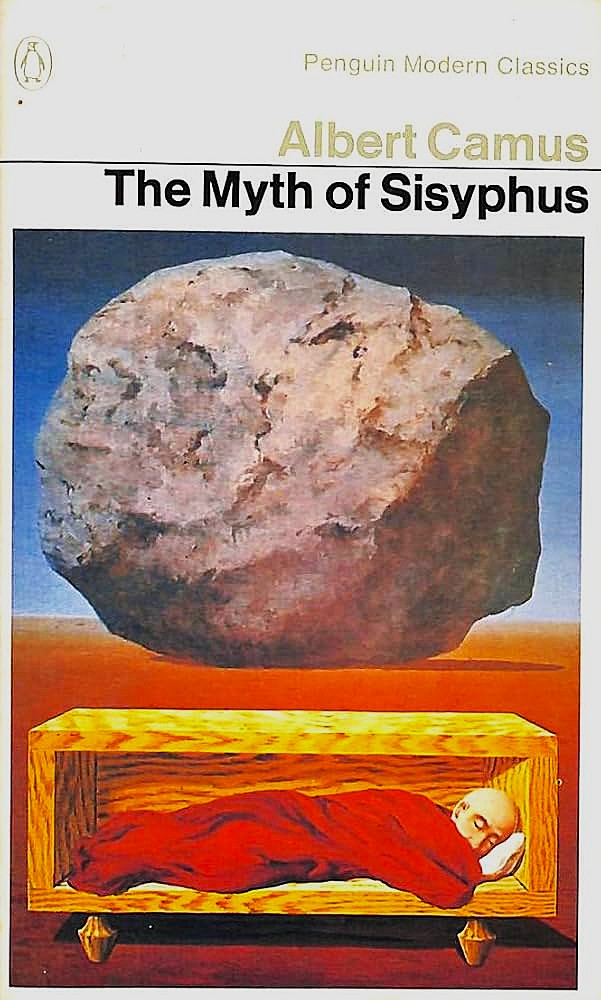

It was actually Camus's The Rebel, L'Homme révolté, which recently made me read The Brothers Karamazov, after with great interest having reread his The Plague during the Covid epidemic.

The Rebel might be considered as a continuation of Camus’ earlier essay The Myth of Sisyphus from 1942, in which he developed the idea that human’s situation is absurd because the world is meaningless, and Camus here occasionally comes close to a cynical nihilism. Humans must shape their own moral values at their own risk and responsibility. Camus speaks warmly of “action without tomorrow”, meaningless activities that constitute an “in spite of it all” in the face of the certainty of death and the meaninglessness of life.

Camus, who suffered from tuberculosis, had repeated near-death experiences (1930, 1936, 1944 and 1949) and it was his choice to become join in the resistance against the Nazis, which gradually led to a partial change of opinion. This shift is apparent in The Rebel from 1951 – life can actually gain meaning by rebelling against the absurdity of existence and a struggle for human dignity.

In The Rebel, Camus has become a moralist and a humanist. However, it is not a “totalitarian humanism” he advocates, not an elite-led revolution intended to “liberate man from the ground up”, such violent actions can only produce new terror and a lack of freedom. Camus condemned all acts of violence and criticized those who considered communist violence and oppression as acceptable means to achieve a humanitarian goal.

Camus's doctrine of non-violence led to a violent break with his former friend Sartre, who tolerated and even advocated the use of violence as a legitimate response to oppressive capitalism and imperialism, thereby justifying communism as a necessary step to defeat them. Camus could not accept such a stance.

By appealing to reason and freedom, one might give terror a semblance of righteousness... but slave camps under the banner of freedom, disable the faculty of judgment

Since his Algerian youth, Camus had been an avid and skilled football player and actor, and he was also devoting himself to directing plays. Early on he had been a devoted Kierkegaard reader, fascinated by his method of using different roles in his writing – Judge William, the Seducer Johannes, de Silentio, Johannes Climacus, Brother Taciturnus, Vigilius Haufniensis, etc., etc. – and in his Sisyphus essay, Camus also introduced various personalities: Don Juan, the Actor, the Conqueror and the Poet, each of whom stood for different attitudes towards the absurdity of life and death. According to Camus, death is our only true reality, it defines human existence and we need to structure our lives in accordance with this fact. His four characters stood for revolt, freedom and passion. To achieve freedom, it was necessary to create indifference to and distance from existence. We have to enable ourselves to extract a maximum sense of joie de vivre, lust for life, enjoy the diversity of life. To be able to free oneself, one had to revolt against that which oppresses and limits us, like religion, totalitarianism, and bigotry.

Don Juan does not believe in God or an afterlife. He is convinced of the meaninglessness of life and overcomes his despair by constantly seeking new moments of devotion, tenderness of the body, pleasure through the senses. The Actor tries out countless life possibilities in his fleeting role creations. The Conqueror is well aware of the fact that actions are vain and meaningless, but does nevertheless choose to be completely absorbed in his actions, whatever they may be – sports, charity, rebellion. The Poet/Artist make use of art as a means to subdue the absurdity of existence. Here we find great writers like Melville, Goethe, Proust and Kafka. They are not any trendy artists, bumbling fools only capable of imitating existence. Great writers create something new by providing surprising insights into our absurd existence.

We are all stuck in the meaningless wheel of endurance, like Sisyphus we constantly drag the heavy stone of our existence up the steep mountainside, only to be forced to experience how it rolls down again. But, if we realize the absurdity of what we have been forced to do, we can perhaps mentally distance ourselves from the misery, the vain toil. One should imagine Sisyphus happy – Il faut considérer Sisyphe heurueux! We should act without tomorrow and thereby revolt against the chaotic absurdity of life, a spontaneous and heroic act of will against nothingness.

Camus identified himself with Ivan in The Brothers Karamazov. He even played the role in the theatre productions, for example 1936 at the Théâtre de l’Equipe in Algiers. In The Rebel he dedicated an entire chapter to Ivan – Rejection of Salvation in which he praised the views of Ivan: “It is not God that I reject, it is the whole of creation!” Ivan believed that justice stood above both God and his Creation. It is man’s duty to uphold justice. Camus is like Ivan tormented by the fact that if God is dead existence is absurd and meaningless. However, … is that really true? In God’s absence, man has the full responsibility for our world and its inhabitants and it is our duty to ensure justice. That cannot to be meaningless.

We all know what justice is and here Ivan points to the cruelty that is committed against children. How can a loving God allow such a thing? An agitated Ivan tells his godly little brother Alyosha about what he has found in recent newspapers – a landlord who let his dogs tear a little boy to death for a trivial negligence. A couple of parents who an entire night locked their three-year-old daughter in a freezing shed where she desperately screamed for help and tore her hands trying to get out. How a soldier let a child play with his revolver, only to shoot him in the face the next moment. To this we can now add 20,000 children killed in Gaza, 1.5 million children killed by the Nazis and countless children who at this very moment are abused and exploited around the world, starving, raped and tormented. It is sickening and both Ivan Karamazov and Albert Camus ask how this can be possible, especially in a world where people still believe in an all-powerful and loving God.

In The Rebel, Camus describes how various, inner and external revolts have taken place throughout history. He describes how the Marquis de Sade, through his atheism and libertinism celebrated a freedom that meant self-satisfaction at the expense of others. How Saint-Just and other revolutionaries during their reign of terror in the name of justice and equality sacrificed fellow human beings for an unattainable utopia. How anarchists and terrorists with legitimate goals murdered and spread terror without achieving any of their objectives. How Marxist ideologues replaced God with history. It would sanctify their means until their utopias were achieved. “History will acquit us!” No, the only thing history has proved is that “what violence may create is difficult and short; it dies away like a desert storm.” And not even that – millions and millions have been sacrificed to gods and “history”.

So, what was the main message of The Rebel? Justice! Against all odds, we must continue to preach justice and equality. Pointless? Why not? What other point is there? We have already seen how the belief in Nazism created death camps and the belief in communism – the Gulag. The revolution eats its children. We know it, we witness it. A revolt should be directed against violent ideologies, against untenable myths, against lies spread by usurpers, imperialists and capitalists. We must protect our children from evil and nature from destruction.

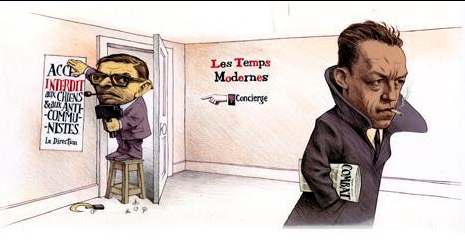

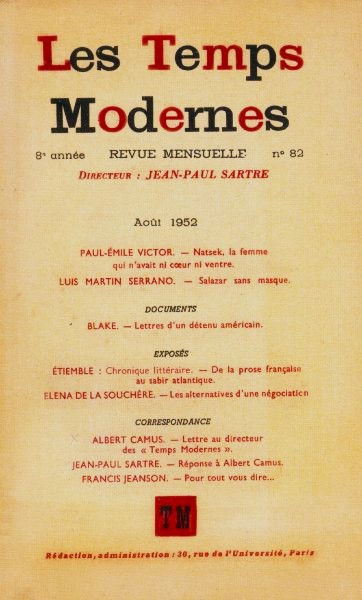

And how was this Plaidoyer d'un fou received by the philosophical establishment and especially by Camus's friend and comrade-in-arms Jean Paul Sartre? As editor-in-chief of the influential journal Les Temps Modernes, Sartre let one of the younger journalists, Francis Jeanson, become his mouthpiece in denouncing Camus's book.

Jeanson had known Camus for several years, but unlike him he was a staunch supporter of the FLN, The Algerian National Liberation Army. Jeanson was a convinced Marxist and took issue with Camus’s denial of history as a benchmark for revolutionary action. According to Jaenson, Camus was a reactionary who condemned the “Marxist experiment” without having anything positive to offer in return. Camus did this in a world burdened by social injustice, in which intellectuals were faced with the choice of either siding with the oppressed, which could only be done by supporting the Communist Party, or “denying history” in the name of “transcendental metaphysics.” Camus's philosophical analysis and rudimentary history were nothing more than “pseudo-philosophy and pseudo-history” and through his book he had now become a traitor to the intellectuals’ struggle against imperialism and capitalism.

Deeply hurt, Camus responded directly to Sartre in an article published in Les Temps Modernes in which he questioned Sartre’s silence concerning Stalinist repression and communist abuses.

Sartre responded with a twenty-page artillery barrage. Under the condescending title Mon cher Camus, Sartre described The Rebel as an unhistorical and reactionary book, which through its political irrelevance had become a tragic culmination of Camus’s entire oeuvre. When Camus, like all other reactionaries allows a critique of Soviet communism to belittle class conflict and imperialism, he sabotages the unifying principle behind a just political action. Instead of pointing out social injustices, Camus puts human nature at the centre, confusing personal interests with class struggle. Something that removes his vaguely defined concept of “rebellion” from the core of a legitimate revolution, making it the basis for a “false solidarity” between the classes. There is no longer any strength, no direction in Camus’ ideology and he has thus made himself completely politically irrelevant. What remains is only libertinage, a freedom without brakes, liberté sans frein.

Sartre wonders whether Camus deserves the label of “engaged intellectual.” The term intellectuel engagé had appeared in Sartre’s and Simone de Beauvoir’s essay Qu’est-ce que la littérature? What is literature? in which they emphasized the role of the writer as a witness of the times with a responsibility to speak the truth and expose injustice. Sartre viewed Camus’s inability to support or identify himself with any current revolutionary struggle as an escape from his intellectual responsibility and a failure at being an intellectuel engagé. He even accused him of being part of the oppressive class he should be working against.

The coup de grâce came at the end of the article when Sartre declared that Camus had now become a “terrorist” through his rejection of history and his passivity in the face of current conflicts.

It is also worth noting that Sartre seems to have been almost excited in his violent attacks on Camus. There was perhaps some wounded vanity and jealousy behind the attack? Sartre was, after all, a privileged member of France’s intellectual class, a well-bred philosopher, the centre of a coterie of mutually admiring writers and debaters. A spoiled son of the upper bourgeoisie. Camus was a proletarian upstart, a pied-noir originating from Algerian poverty, admittedly an excellent writer, with a solid philosophical background, though not as sophisticatedly educated as Sartre.

Despite their different backgrounds, the two writers had previously gotten along quite well, drinking and having fun together. Camus had appreciated Sartre’s education, while he had found Camus’s scabrous humour unusually stimulating. They had had such a good time together that even de Beauvoir had become jealous.

But … Camus was handsome and Sartre ugly; small and wind-eyed, he envied Camus’s charm and his positive influence on the other sex. We might look at Camus in a photo by Cartier-Bresson and thus understand why he was compared to Hollywood stars like Bogart and could half-seriously joke that “I can get a movie contract whenever I want.” The trench coat collar is turned up, the hair combed back, a cigarette in the corner of his mouth; a long, masculine, furrowed face, with an active, warm gaze.

The contrast to poor Sartre is striking:

While noting their differences, it might also be opportune to acknowledge their shared opinions. For example they both had in common a deep-felt admiration för the works of Dostoevsky and in particular The Brothers Karamazov. Sartre wrote: