Honoré Daumier’s Sincere and Impeccable Art

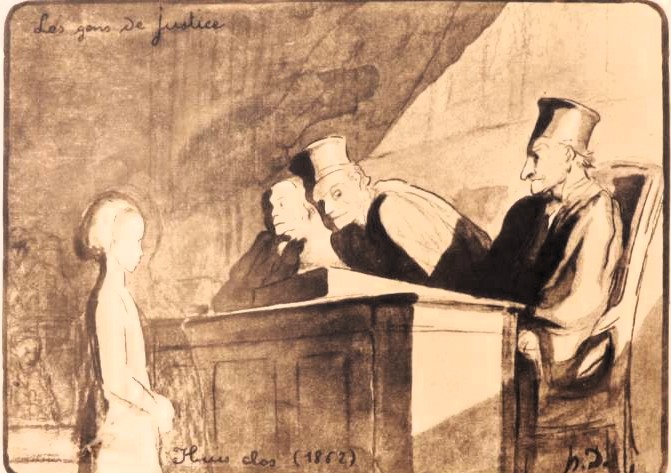

Many years ago, my oldest sister gave me a lithograph. At the time, she was a flight attendant and had bought it from some bouquiniste in Paris. Certainly, it was not an original, but I have never cared about that, the main thing is the subject – in this case, the lithograph was by Honoré Daumier (1808–1879) and I had it above my bed for several years. It depicted a thin, almost transparent little girl in front of a group of lawyers/judges.

Why had she ended up there? Had she committed a misdeed? Been the victim of crime, or witnessed one? One of the lawyers/judges turns to the viewer. Has anyone said something that caught his attention? Has anyone entered the room and interrupted the proceedings? Accordingly, the viewer becomes part of the drama. I fantasized and dreamed about that lithograph. It was unique; vivid, strange. A fragment from a long-forgotten time.

Daumier? Who was that? He made more than 500 oil paintings, 1,000 watercolors, 1,000 woodcuts and more than 4,000 lithographs, all of them of highest quality and quite unforgettable. One of my brothers-in-law gave me a book with Daumier's lithographs and I never tire of looking at them.

A gold mine of thought-provoking satire, where the independent anarchist Daumier, in a radiant mood, scourges and laughs at the monarchy, the aristocracy, the clergy, the politicians, the judiciary, the lawyers, the police, the detectives, the rich, the military, the bourgeoisie, all his countrymen and human nature in general.

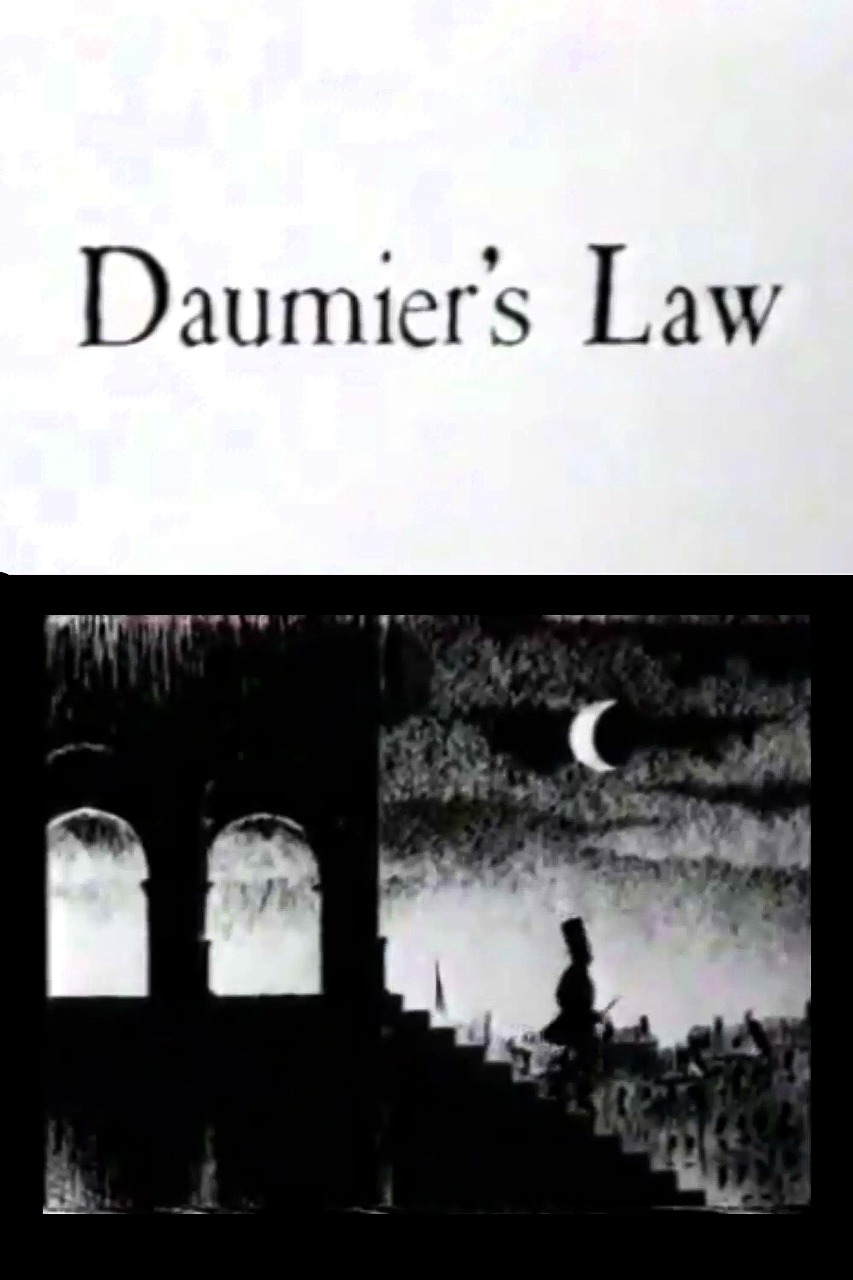

To my surprise, Paul and Linda McCartney made a short film in 1993 called Daumier’s Law. Linda was a professional photographer who had been interested in art since childhood and was particularly fascinated by Daumier. Her mother was a fashion designer and her father a lawyer specializing in legislation related to the art- and entertainment industry. among his clients he had famous artists such as Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko.

Linda’s interest in Daumier inspired McCartney to compose minimalist music to Daumier's images; simple, modernist pieces, based on themes from Daumier’s art – markets, courts, Don Quixote.

McCartney contacted the artist Geoff Dunbar, who in 1984, together with the McCartney couple had created made an animated short film – Rupert and the Frog Song, which told a story about how the bear Rupert one evening had ended up in a mysterious underground place where frogs every hundred years performed a ritual show, while singing a charming song by McCartney – We All Stand Together, arranged by the “fifth Beatles”, the producer George Martin.

The music video was broadcast time and again on MTV. We were by then living in the Dominican Republic, where the music video channel was broadcast several years before it appeared in Europe. My then two-year-old daughter was very fascinated by McCartney’s frog song, cartoons tend to delight kids, in particular if they are well made. The Rupert film had the aspect of a vintage Disney.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6PMiP90ntZ8

A friend of mine once stated that it was John Lennon who provided the Beatles’ repertoire with its specific flavour, its salt and depth, while Paul McCartney stood for a “superficial folksiness”. He considered Paul’s tunes to be easy-going “pub songs” and that that was all he had produced since the Beatles broke up, apart from some efforts to produce some unsuccessful attempts at highbrow orchestral pieces. Perhaps my friend was right to some extent. In any case, the film Rupert and the Frog Song was deeply rooted in English folksy, children's tradition.

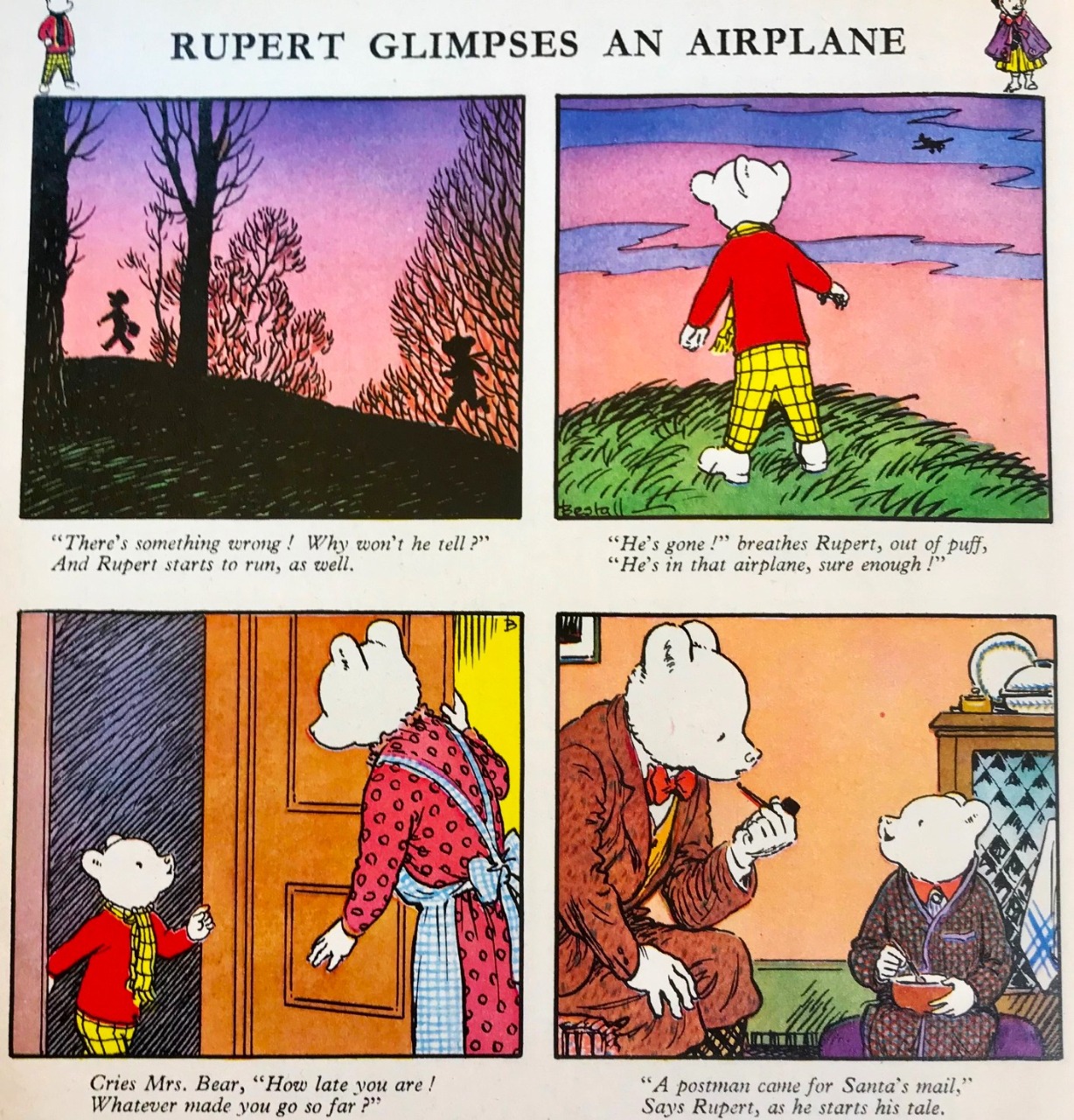

Rupert is an English children's cartoon character created by a certain Herbert Tourtel and illustrated by his wife, Mary. In 1920, Rupert appeared in the Daily Express, where it still lives on.

Rupert is a very English phenomenon. The little, lovable bear who lives with his pipe-smoking, gardening father and housewife mother in a cozy cottage located in a bucolic Nutwood. Each story begins in that cottage from which Rupert usually sets out on a small errand for his mother, or to visit a friend, the story then develops into an adventure in an exotic place, such as King Frost’s castle, the Kingdom of the Birds, in the underworld or at the bottom of the sea.

The stories about Rupert have become an integral part of English children’s culture and have given rise to countless children’s books, films, TV series and dolls. McCartney and Dunbar’s short film is a loving tribute to this cozy, safe and at the same time exciting world. And ... the frog song is for certain an excellent "pub song".

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WfEyEp62-l4

Well, it was natural that Paul McCartney turned to the congenial Geoff Dunbar and asked him to make a short film based on Daumier’s world, based on McCartney’s minimalist music and his and Linda's script. The result is fascinating, especially for someone familiar with Daumier’s art. Almost every sequence alludes to one of Daumier’s many works of art and the animation is skillfully done. The film can actually be considered as an excellent introduction to Daumier’s production.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V-WlJ3ZXZc4

In these times of Trumpism silencing all valid criticism of his regime, which back by Mammon’s minions is back suffocating free speech, my admiration for the shrewd and fearless Daumier has increased even more.

In a previous blog post I gave an example of how even the insignificant me had been silenced by Trump’s stupid censorship, which like a nauseating lump of dough has settled above U.S.’s free speech and in a scandalous fashion has tried to silence comedians like Jimmy Kimmel and Stephen Colbert.

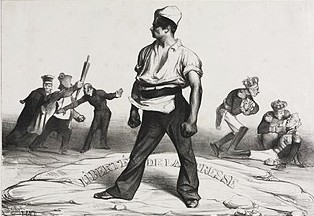

I look with appreciation at a lithograph by Daumier in which the Free Press has dealt a fatal blow to backward monarchy and is preparing to battle representatives of the bourgeoisie and capitalism.

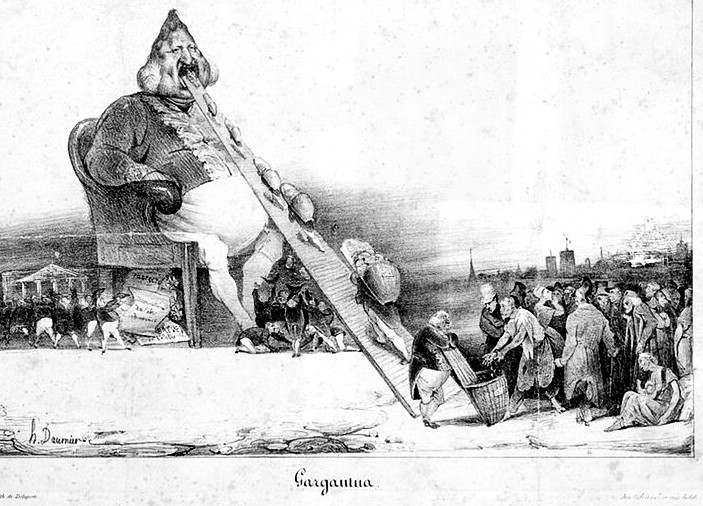

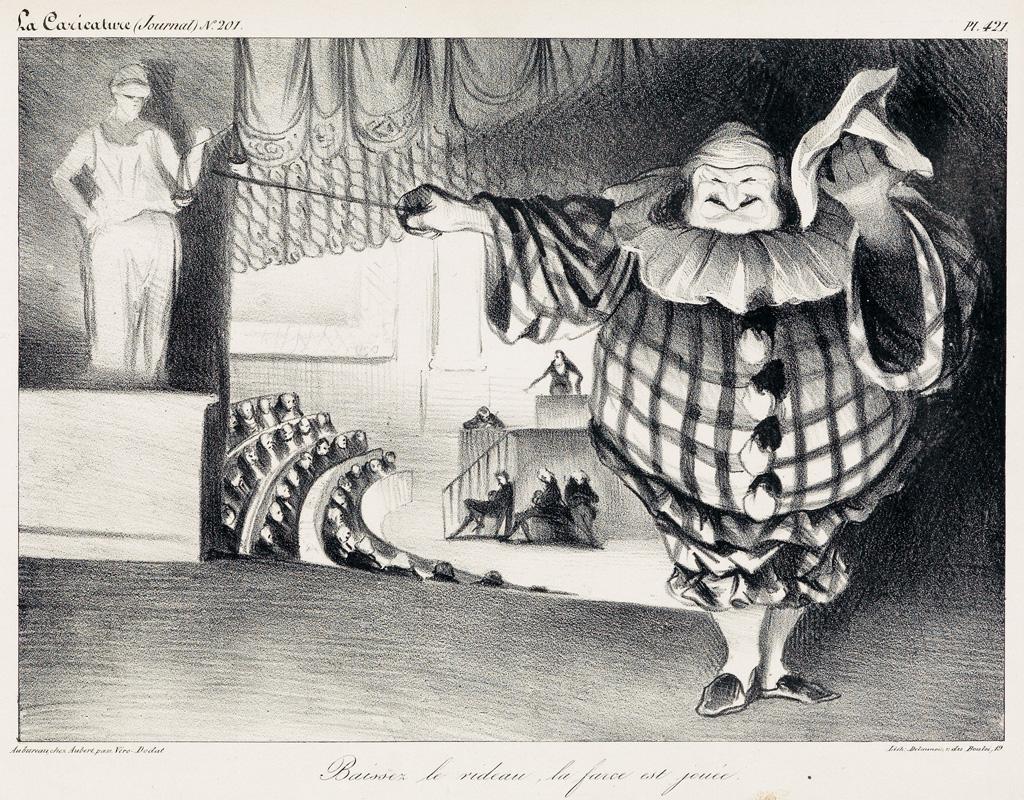

When Daumier made this lithograph, he had already fallen out with the Trumpists of his time. In 1831, in the satirical magazine La Caricature, Daumier had depicted King Louis Philippe I as the giant Gargantua, into whose mouth an increasingly impoverished French population is forced to deliver load after load of its hard-earned income.

The following year, Daumier was put on trial and accused of “inciting hatred and contempt for the government, and insulting the king.” He was sentenced to six months in prison and a fine of 500 francs. However, Daumier’s fame had already become so great that loud protests were raised against the verdict. The great writer Balzac exclaimed, quite rightly: “This guy has Michelangelo in his blood!” The verdict was postponed, but Daumier did not remain silent.

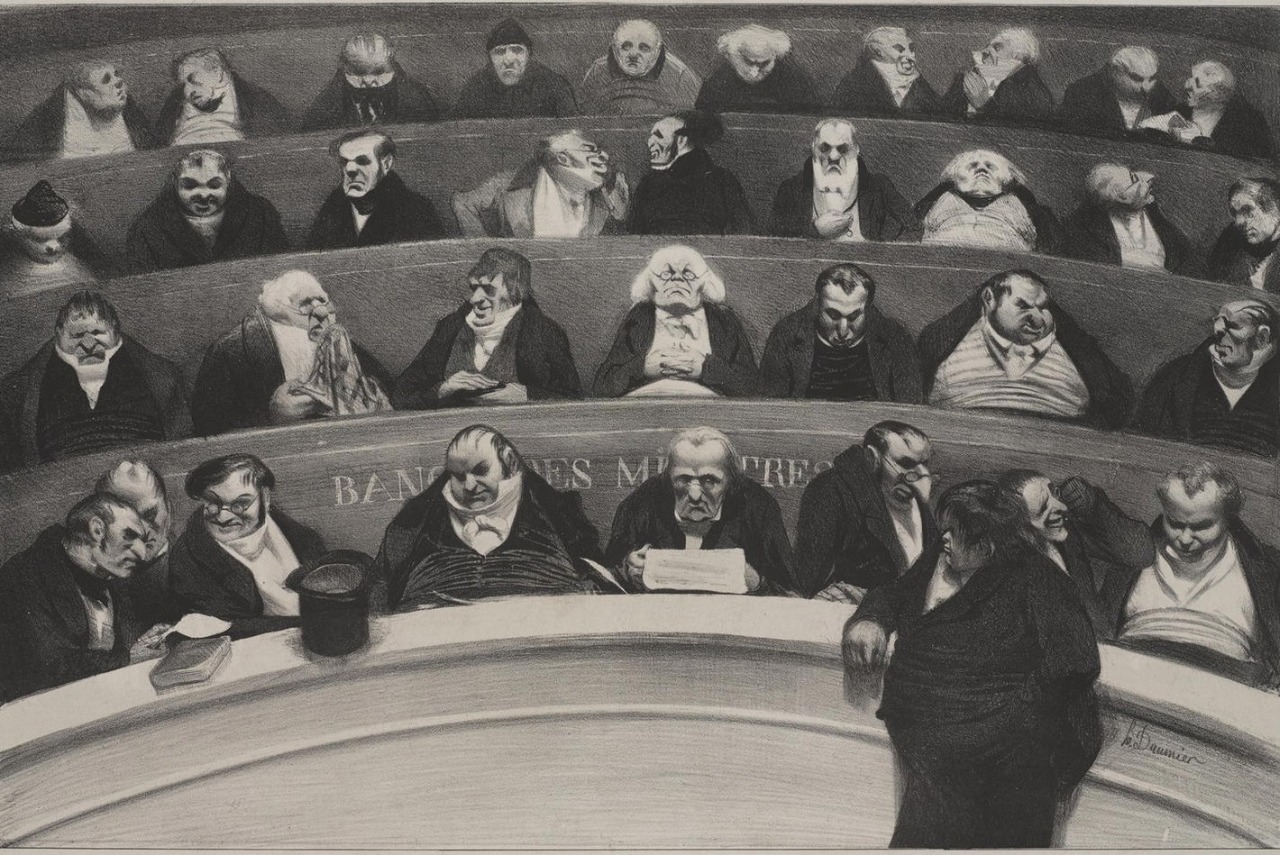

Later that year, Daumier published a picture he called The Court of King Pétaud in which he caricatured the submissive cabinet of King Louis Philippe I. You do not see the king himself, but a submissive queue of his sycophantic ministers humiliating themselves before him.

.jpg)

This time, Daumier was arrested in his parents’ apartment and placed in the Sainte-Pélagie prison, where he served six months. In prison, Daumier continued to produce his anti-government drawings, which were smuggled out, according to him, to ”further irritate the government.”

The expression King Pétaud's court probably originated from a time when Paris beggar community appointed a leader whose title was Roi Pétaud, from the Latin peto, I pray. This potentate ruled from the Cour des miracles, the Court of Miracles, which referred to a slum area where unemployed migrants from the countryside lived. It was a refuge for poor people who had settled there to hide ways from authorities, who did not dare to enter the mob-ruled quarters. The place was called the Court of Miracles because the lame could walk there and the blind regained their sight, an allusion to the fact that many of those who begged in the streets of Paris did so under a pretence of suffering from various ailments, which they in fact were faked in order to arouse empathy.

In Victor Hugo's 1831 novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame, the poet Gringoire thoughtlessly wanders into the Court of Miracles where he encounters Clopin, whom he had previously thought was an ordinary beggar, but now turns out to be King of the Truands, the criminals and outcasts of Paris. Clopin sentences Gringoire to death for “unlawful trespassing,’ but at the last second, Gringoire is saved by the beautiful Esmeralda who agrees to marry him. Clopin appears in Disney's version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

Daumier's reference to Hugo’s contemporary novel and its beggar king could hardly have escaped the Parisian reading public. Louis-Philippe I had initially been relatively popular. Since he owed his throne to a popular revolution, he was called the Citizen King, and his supporters further praised him as King of the Barricades underline the popular sympathies he enjoyed and the king’s outward appearance of modesty. In fact, Louis Philippe’s regime found its support among the wealthy bourgeoisie. His reign was actually dominated by a close-knit group of wealthy industrialists and bankers.

Under the leadership of the Citizen King, the conditions of the working class deteriorated, whole the income gaps widened considerably. Already at the beginning of Louis Philippe's reign, several Parisian intellectuals had noticed that the Government was in fact a plutocracy ruled by the country's wealthiest capitalists, entirely in accordance with their self-centred interests, and beneath the populist surface, class oppression increased, while denunciation spread and opposition was silenced.

Of course, there were no annoying TV comedians at that time, but the satirical press, with newspapers like La Caricature and Charivari, Hullabaloo, relentlessly scourged King Louis-Philippe and as is the case now with Trump nowadays, ridiculed the king’s statements and appearance. The King’s tail of minions and flatterers did everything in their power to silence all criticism

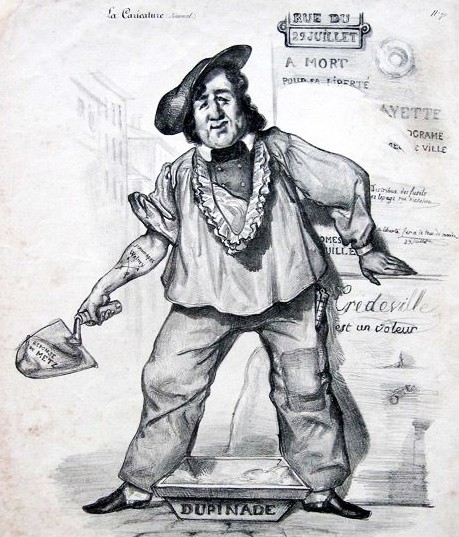

Famously, the caricaturist Charles Philipon was accused of having mocked the king when La Caricature had portrayed Louis Philippe as a bricklayer in the process of covering up the slogans and leading names of the so-called June Revolution, which actually had brought him to power.

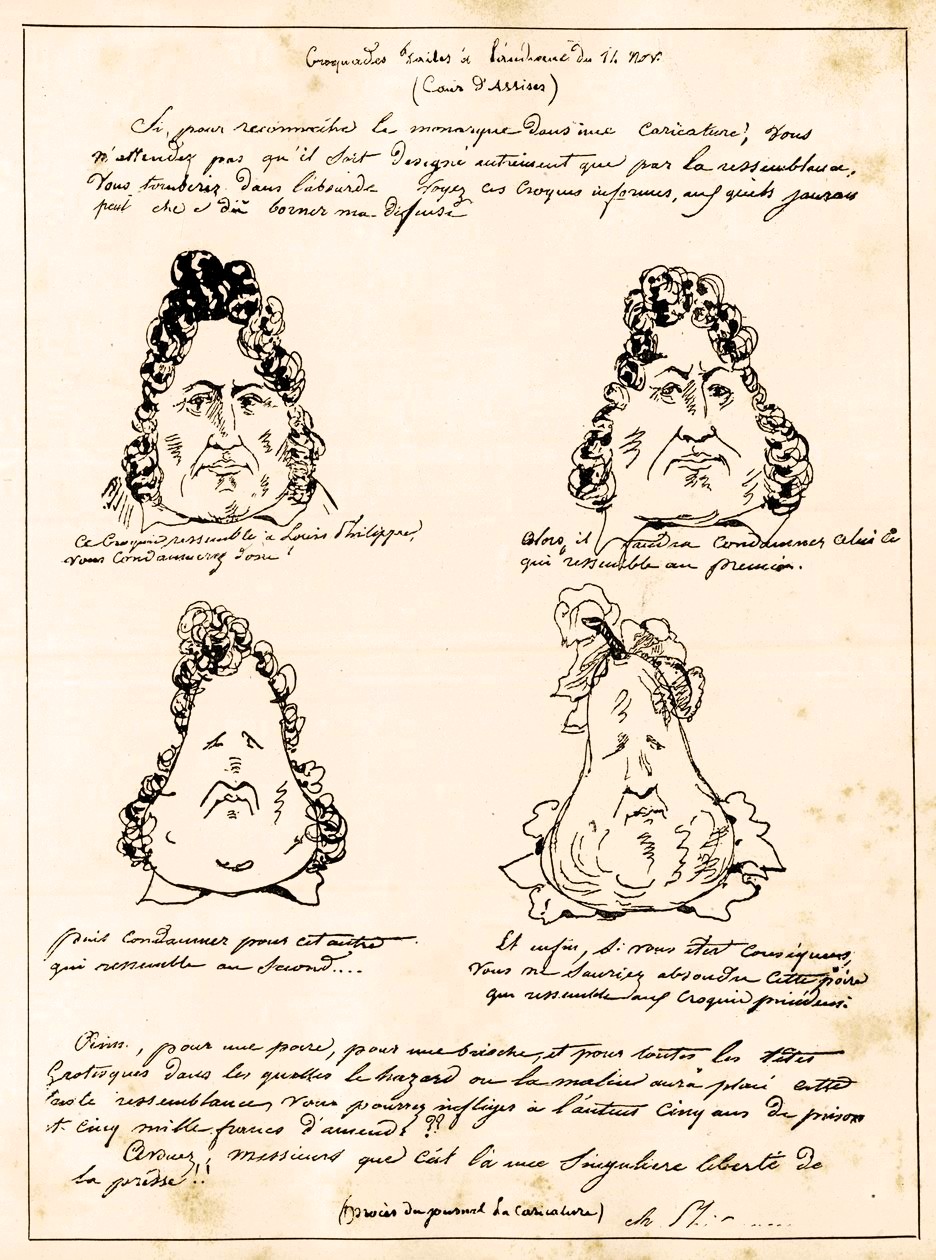

In an ironic defence, Philipon wondered how the Court could be sure that it was really Louis Philippe the First that he had depicted as a bricklayer, after all, the king could be likened to anything, for example to a pear.To clarify this claim, Philipon demonstrated a drawing he had made in which Louis-Philippe was gradually transforming into a pear.

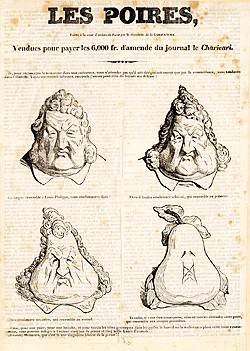

Philipon was in 1831 sentenced to six months in prison in Sainte-Pelagie, where Daumier was already confined, and on top of that, Philipon was sentenced to 2,000 francs in fines and another seven months for additional offenses. However, the famous pear drawing was in 1834 reprinted in Le Charivari and soon spread beyond the borders of France.

The result was new fines for Le Charivari, which several times before had been charged with slander and sedition. To raise money to cover the fines,Le Charivari once again printed the pear image, this time as a separate broadsheet sold for two sous. It was now apparently Daumier who had made a new version of Philipon's original drawing

Daumier’s struggle against censorship and other oppression was not only expressed a satirical manner. He could also create serious illustrations that expressed his dissatisfaction with the regime’s poorly concealed terror. For example, when protests broke out in 1834 and Louis-Philippe’s militia opened fire on a residential building, assumed to be occupied by rebels, a number of completely innocent families were massacred instead.

A dead father is depicted lying dead in his bloodied nightgown and fallen across his child that has been crushed by his weight. The picture clearly indicated how unprotected innocent had been killed in cold blood. Daumier's good friend Charles Baudelaire praised the mundaneness of the image, which despite its cruel reality, or perhaps because of it, had become a monumental act of accusation worthy of a Shakespearean drama: “Here only silence and death are reigning."

Daumier saw the greatness of simplicity. By depicting the everyday life of the French people, he elevated it to great art. Here, no classical education was required, no imitation of the academies’ high-ranking artistic ideals. Artists had to walk down into the alleys, down to the people.

The peasants of Jean-François Millet

against the ancient Romans of Jacques-Louis David.

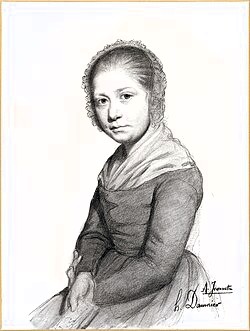

Daumier came from a poor family. His father, Jean-Baptiste, was a glazier who framed pictures, sold graphic prints, and wrote poetry. Some of his plays were staged by traveling theatre companies and modest success made him to move to Paris in 1814, followed by his wife and six-year-old Honoré. The financial success was minimal. One of Jean-Baptiste's poetry collections found a publisher, but only a few copies were sold. An amateur theatre group staged one of his plays, but there was hardly any audience. The picture framing business was a failure and the family lived in poverty. Honoré’s indebted father went bankrupt and at the age of twelve Honoré was forced to work as an errand boy for a huissier de justice, a profession unique to the French legal system.

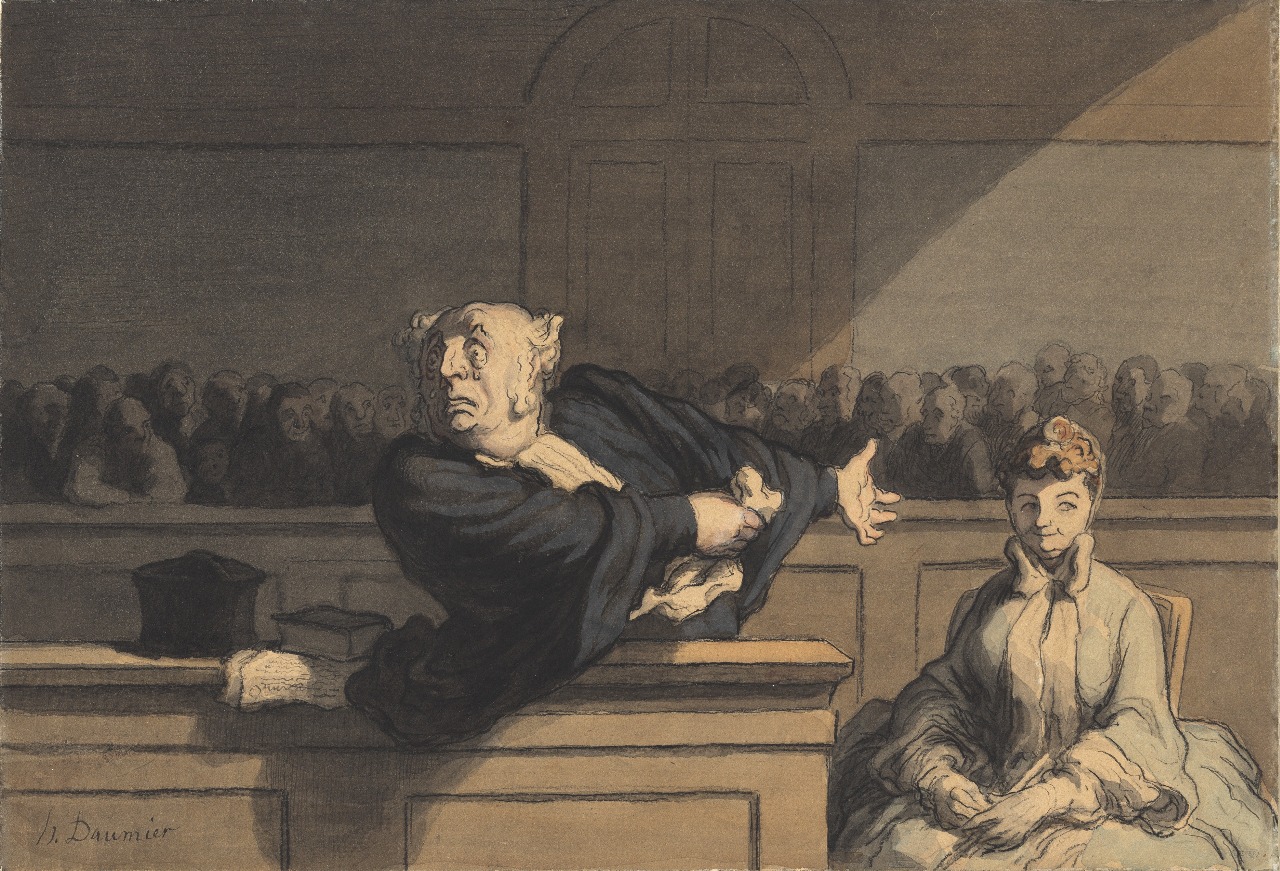

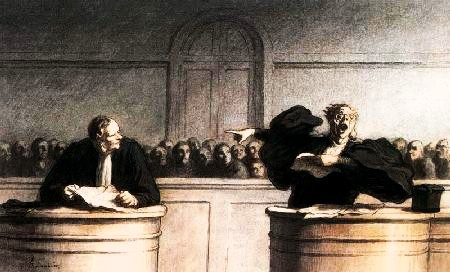

A huissier de justice is a minor official within in the judiciary who forwards summons, enforces and collects court and legal claims, including bankruptcy, property claims, seizures and evictions. An activity that probably made the young Honoré both fascinated by, and disgusted with, representatives of the French legal system. In any case, he devoted a large part of his art to portraying lawyers in full operation. They might force tears to appear while defending of their clients,

indulge in numbing rhetoric, marked by dramatic acting,

Lose themselves in pious speeches devoted to exonerating a client, as here where a lawyer refers to the crucified Jesus to arouse sympathy for a woman who has broken down behind his back.

Lawyers and judges are intriguing in courtrooms and corridors.

As masters of life and death, courtiers are with solemn steps advancing through the palaces of justice.

But their eloquence doesn’t always succeed in persuading their colleagues.

And the clients they manage to acquit are not always God’s best children.

Daumier knew from own experience that controllers of legal and political power were not to be trusted and he attacked them mercilessly, letting their exteriors reflect their interiors. He filled the image of a legislative assembly with a menagerie of unpleasant characters.

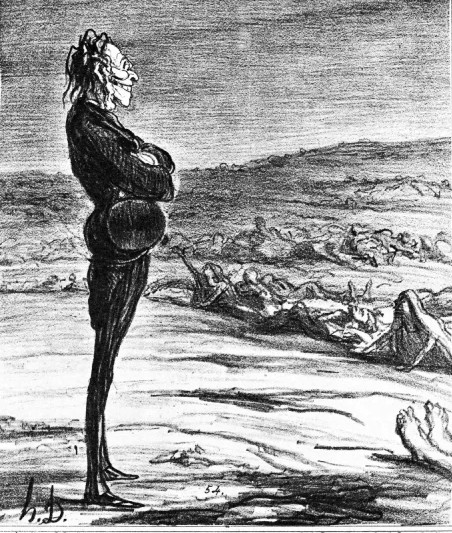

Daumier’s artistic skills were not limited to painting and printmaking, he was also a master sculptor, as in his statuette of Ratapoil, the Rat Skin, one of Louis-Napoleon’s bat-armed provocateurs, whose job it was to incite crowds, often through violence and bribery. A swaying, strutting figure with a goatee and a rumpled hat.

For his own amusement, Daumier made in clay, which he fired and glazed, a number of portraits of parliament members of– here we see an aristocrat, a banker and a bourgeois with an angered, bright red face.

It was different when Daumier portrayed working people. Like the washerwomen who toiled along the banks of the Seine.

Workers and poor people.

Refugees:

Daumier took offense at warmongers, as here in the image of a satisfied inventor of the needle rifle, a weapon equipped with a needle-like firing pin that revolutionized the contemporary arms industry.

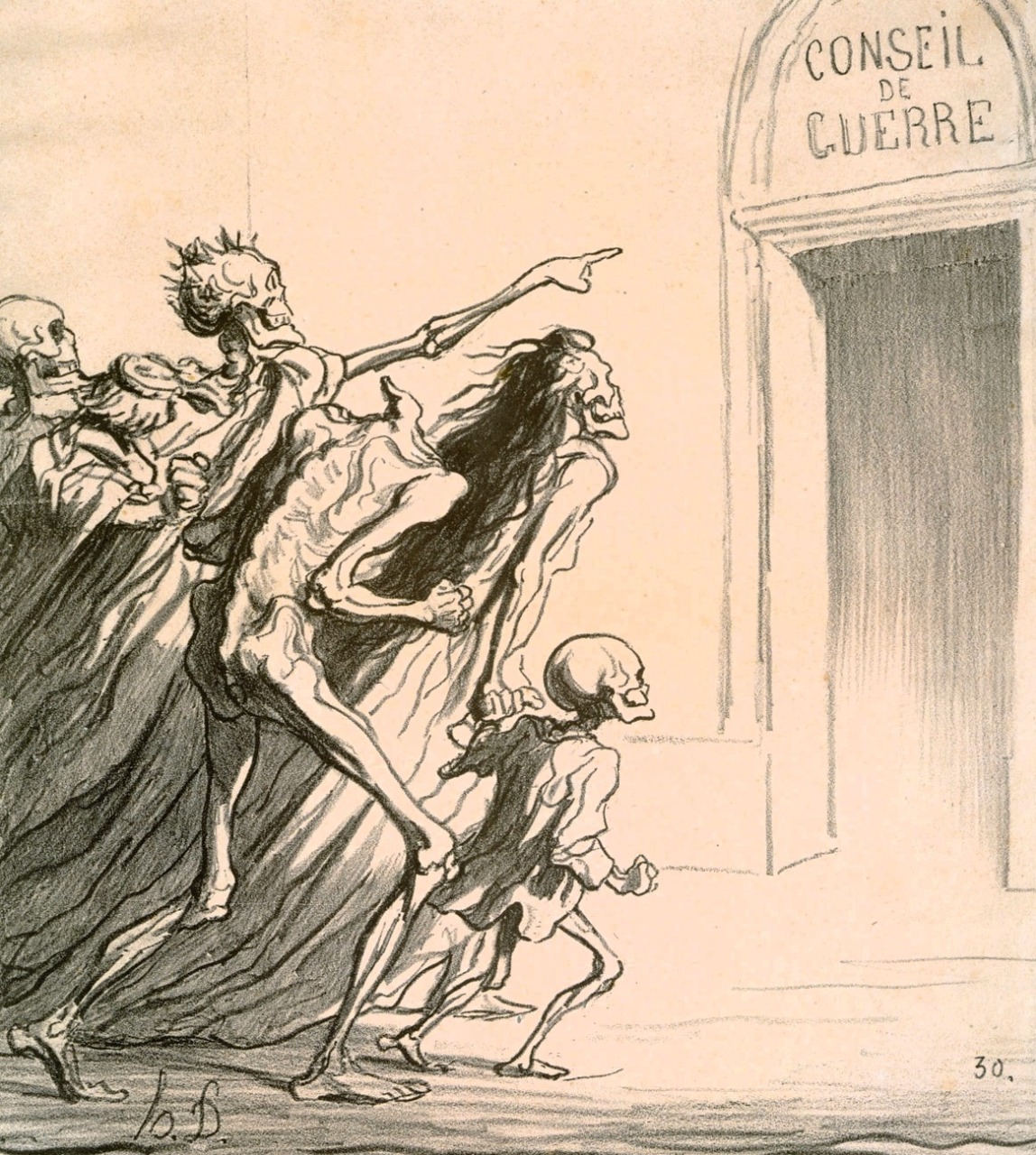

His vision of skeletons and corpses advancing towards a War Council caused the censors to ban its publication.

With his proletarian roots, Daumier was well aware of class differences and found various ways to depict them, as in his image of a first-class train compartment:

its second-class equivalent,

and a third-class compartment:

What I find most remarkable about Daumier is his artistic mastery, which seems to have sprung from a vein of unknown origin and becoming paired with a razor-sharp ability to observe. Without a complete education, Daumier seems to have been endowed with an instinctive feeling for the possibilities and dynamics of oil painting, sculpture and graphic art.

Boldly and uninhibitedly, he threw himself into all varieties of art and did so with a bravura and self-satisfaction that often seem to have been blind and deaf to the tastes and demands of the market. His oil paintings, for example, were virtually unknown to his contemporaries.

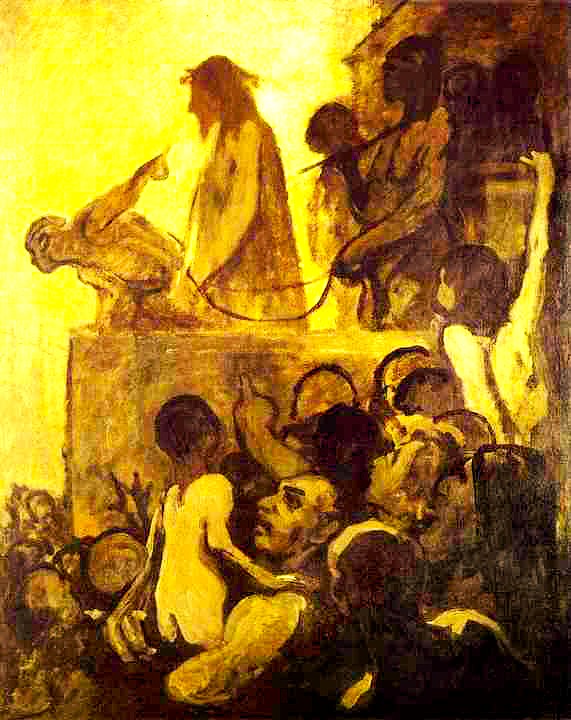

If Daumier ever made an excursion into the generally profitable field of religious art, it was in the form of intensely personal interpretations, emerging from an empathetic, highly personal perspective, as in his Ecce Homo, depicting how Pilate presents Jesus before the people. A rendition that could not possibly interest any wealthy religious potentate.

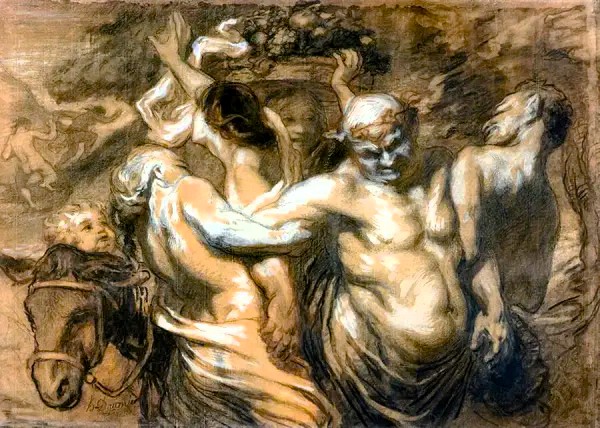

If Daumier was inspired by his visits to the Louvre, it was mostly evident through his sumptuous depictions of bacchanals, based on predecessors like Jordaens or Rubens.

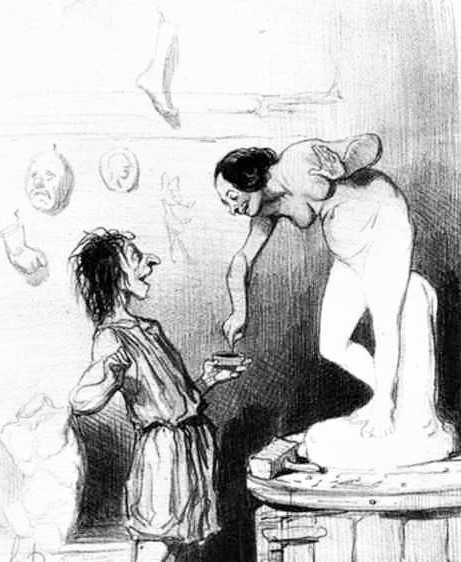

Otherwise, Daumier amused himself by parodying classical mythology, often seriously worshipped by academic painters. Like when Pygmalion has created his Galatea and she after coming to life helps herself from the snuffbox of her sculptor.

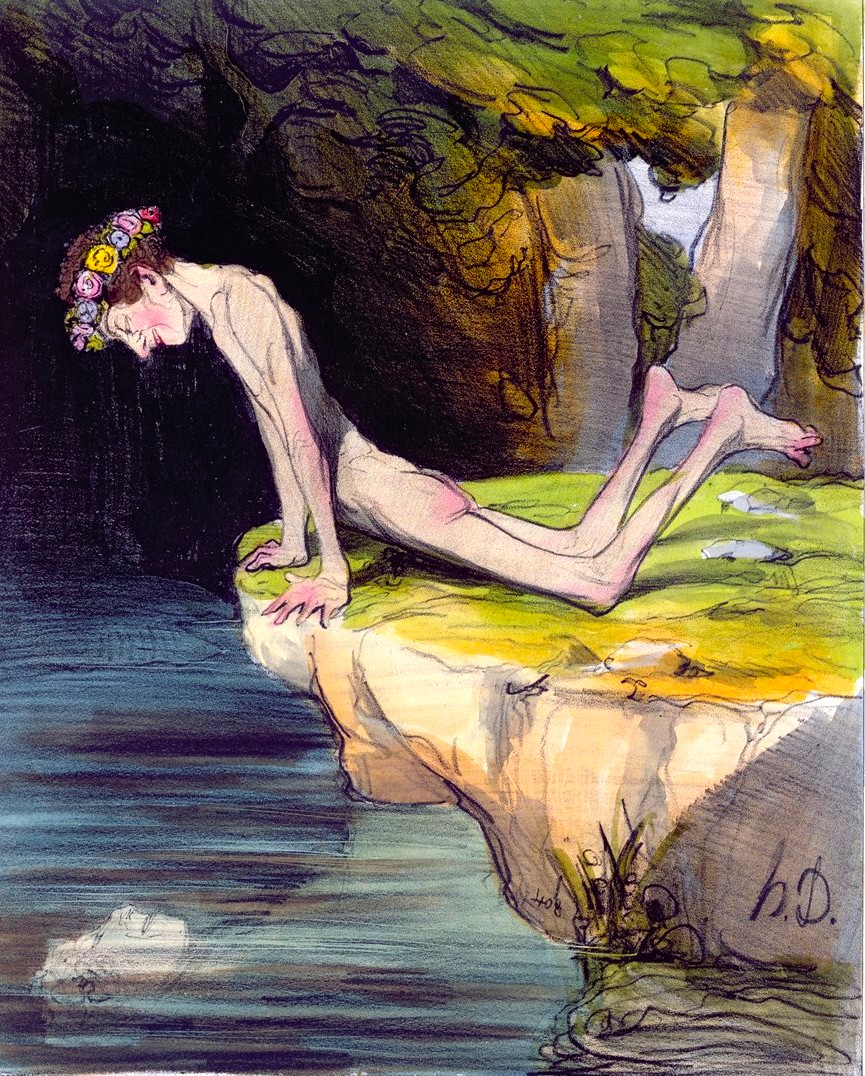

Or a rather skinny and intimidating Narcissus is falling in love with his reflection.

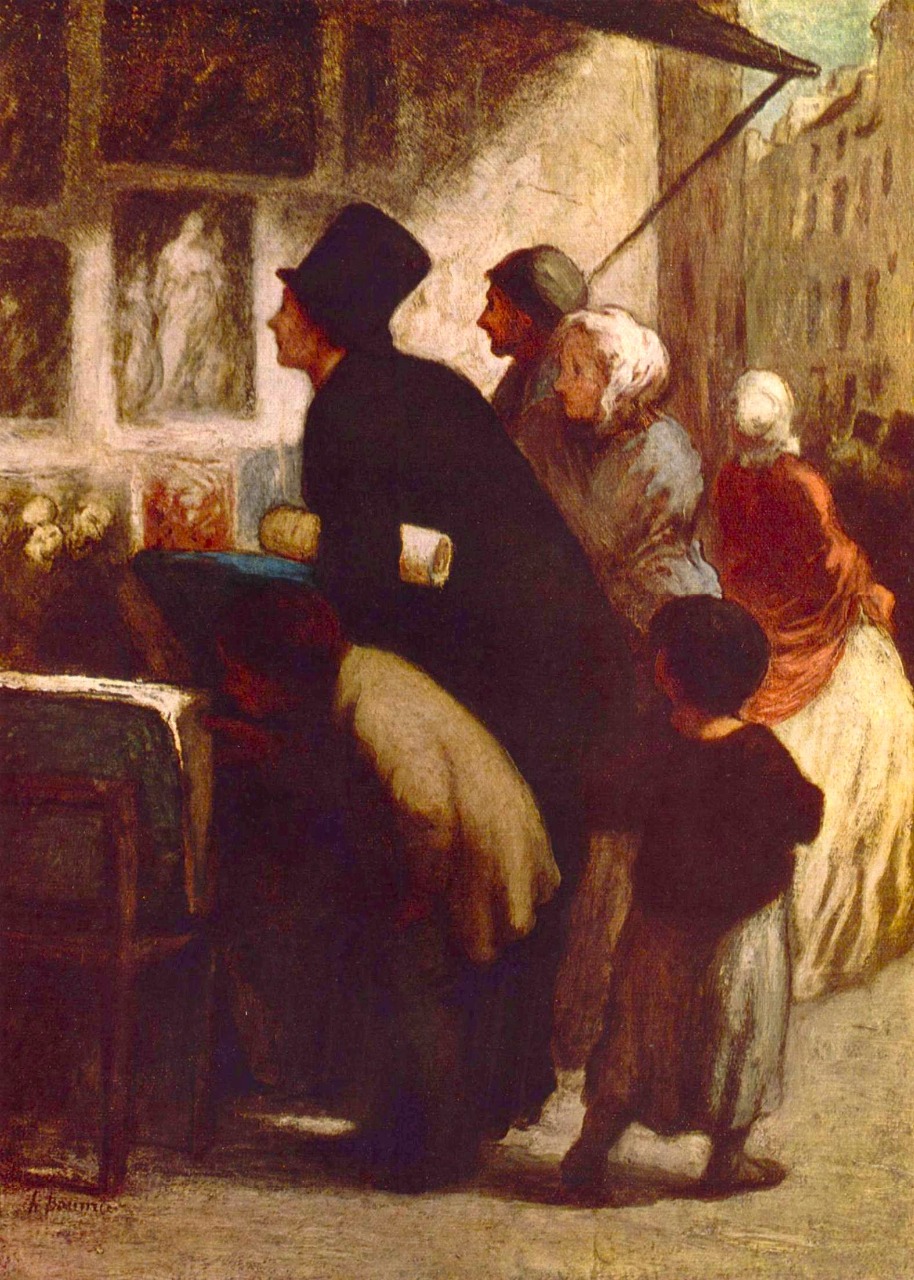

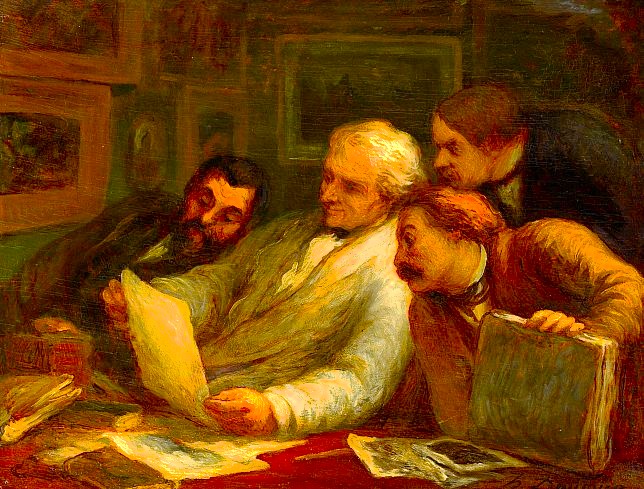

Daumier’s father dealt, as most frame makers still do, in graphic prints and other inexpensive art.

Among those who visited his office were certainly the occasional artist and bookseller.

It was probably his father's connections that eventually led Daumier to an employment at Delaunay’s, a well-established bookstore located among the arcades of Palais-Royal, constituting a hub of Parisian art life, where the young Daumier could meet influential writers and artists, who stimulated his great interest in art. He drew daily and visited the nearby Louvre.

A good friend of his father, Alexandre Lenoir, founder of the Musée des Monuments Français, discovered Daumier's talents, took him to art exhibitions and ensured that he entered the Académie Suisse, where Daumier got the opportunity to draw from live models and was able to demonstrate the artistic skills he already possessed.

Soon Daumier was working with the newspaper printing houses and had perfected his demand of lithography, while his satirical talent and keen powers of observation became greatly appreciated. Although he never became wealthy through his art, Daumier was able to support himself and his wife, a seamstress named Marie-Alexandrine Dassy, with whom he begot son who died while still an infant. Daumier remained faithful to his wife throughout his life.

Marie-Alexandrine did not at all understand her husband's art and did noy keep any of his art work. After Daumier's death in 1879, his widow sold his entire production for a total of 1,500 francs. Among the buyers were several of Daumier's artist friends.

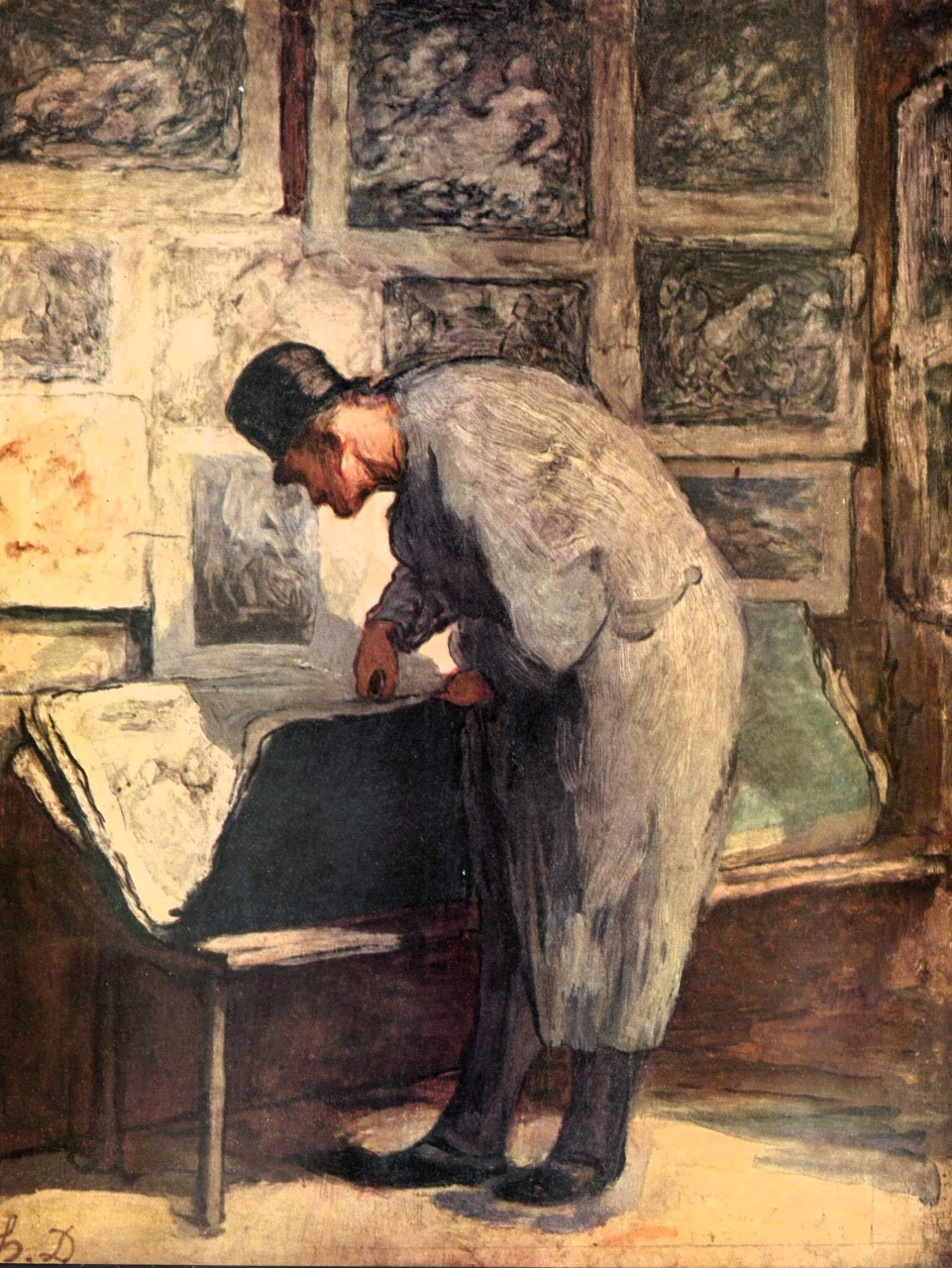

Daumier was a socialite, but did not leave behind many easily identifiable portraits. However, among his many pictures we find many depictions of friends looking at a works of art together.

playing chess,

or taking a walk through a nightly Paris.

He also often depicted artists in the process of painting, but these are obviously neither self-portraits, nor pictures of any identifiable artist friends.

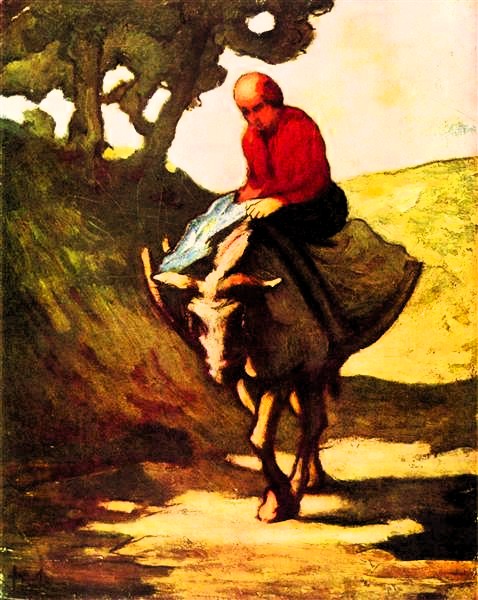

Daumier was a distinctly urban man and made very few landscape paintings.

and it is rare for any peasants to appear in his paintings.

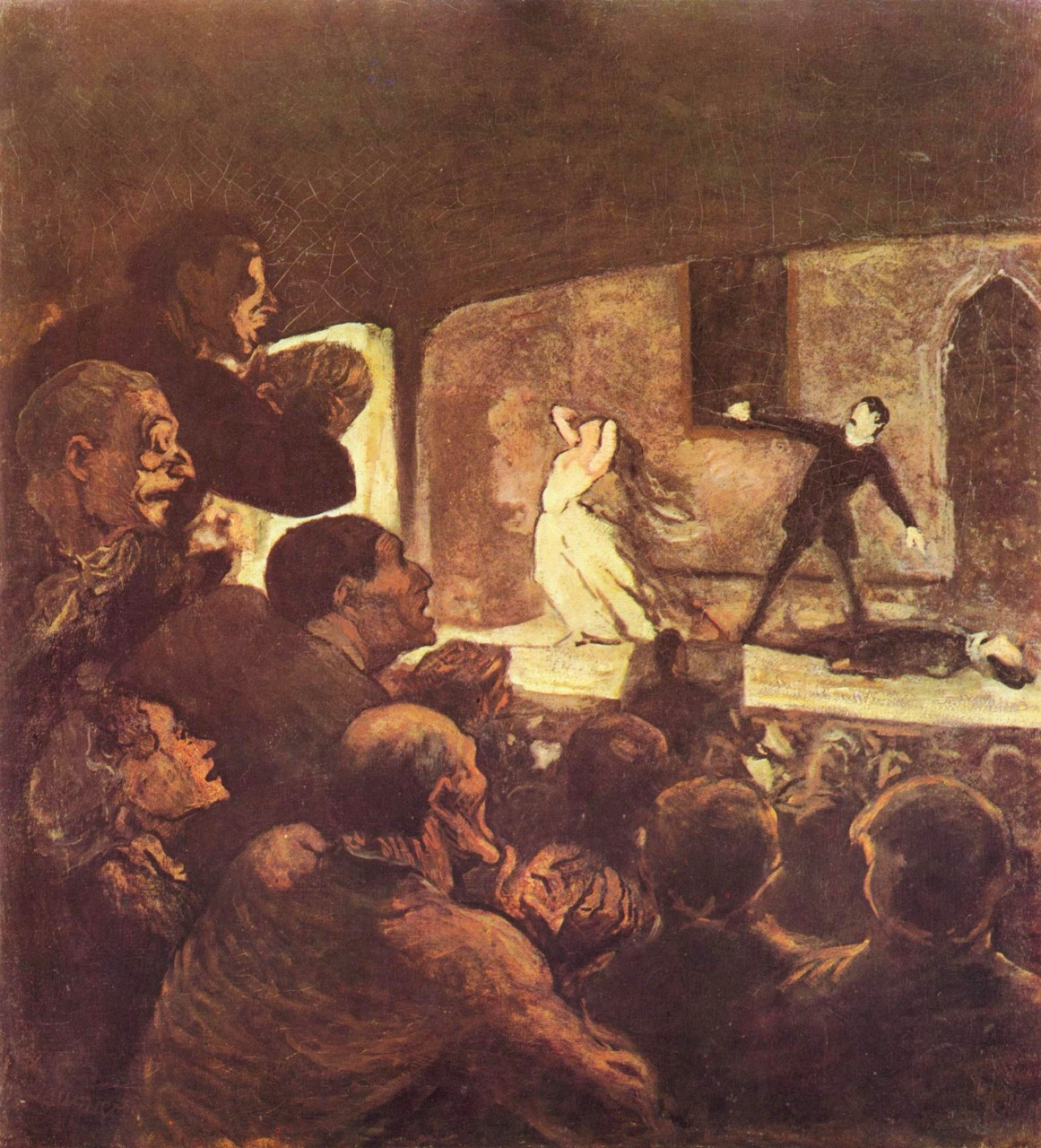

Much of Daumier’s output concerns Parisian theatrical life. He devoted his art to what happened on stage, often in such a way that the viewer gets the feeling that the artworks capture the mysteriously unnatural lighting of the theatres. As here in a production of Molière’s Le Malade imaginaire, The Imaginary Invalid.

In a series of paintings, Daumier depicted a scene from Molière’s Les Fourberies de Scapin, Scapin’s Deceptions, a Comedia dell’arte-inspired play with a multitude of complications, most of which originate from the manipulations of the cunning valet Scapin. In the scene depicted by Daumier, Scapin is hatching plans together with another valet, here called Cispin, but generally named Silvestre.

Daumier’s image is endowed with a demonic aura that has fascinated me since I first saw it. Scapin is observing something with a calculating gaze and a Mephistophelian smile, while he is listening to something Cispin whispers in his ear – is it common slander, or a diabolical plan?

.jpg)

The image has a suggestive power reminding me of another whisper depicted in a painting by the Italian Francisco Hayez, painted 25 years earlier and placed in Venice. It is called Vengeance is Planned and it also provides a somewhat lugubrious impression.

Daumier dedicated at least two more oil paintings to Scapin and Cispin, also dramatically imaginative.

Daumier was not content to simply follow the events on stage. True to his habits, he observed and interpreted his surroundings as well. With his sharp gaze, he noticed how a bored musician yawned in the orchestra pit during a long-winded opera performance.

He turned his gaze towards the upper galleries, where poorer spectators had their seats and saw how they intensely following the dramas unfolding on stage.

Or the commotion that could erupt when emotions overflowed and disagreements turned into fistfights.

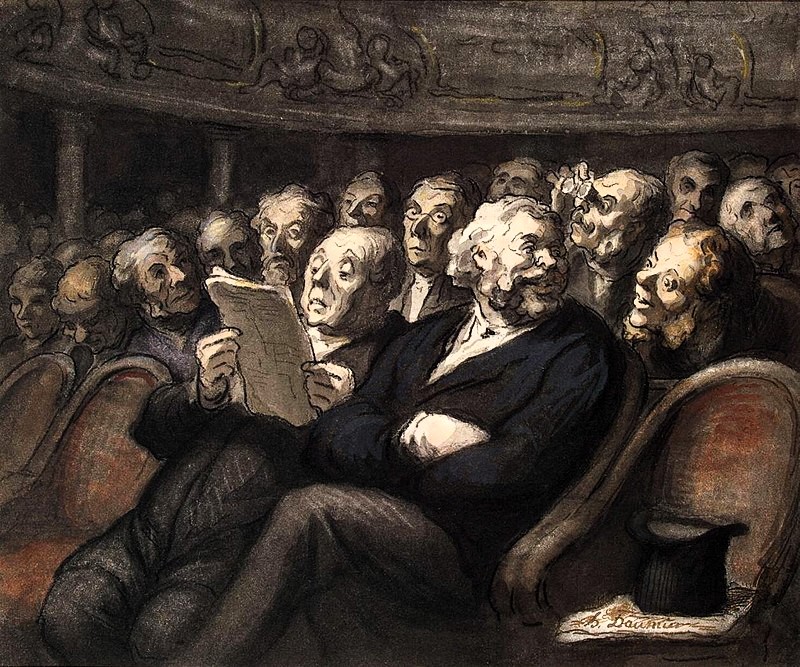

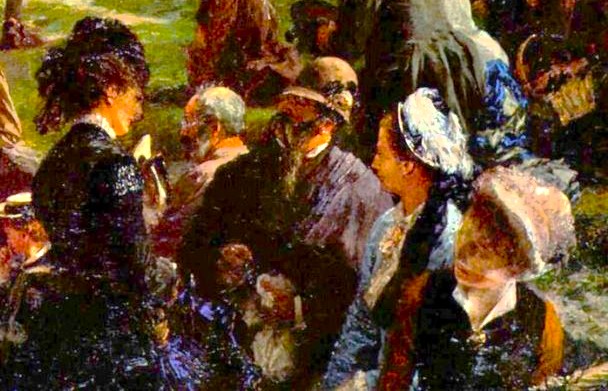

He could also move around among the wealthier spectators further below and observe how they spent breaks between acts.

Daumier is an expressionist of a rarely seen kind, though he also has a lot in common with the Impressionists. Like the picture depicting another groups attentive spectators.

This painting makes me think of artists like Degas and Manet and perhaps even more of the contemporary German Adolph Menzel.

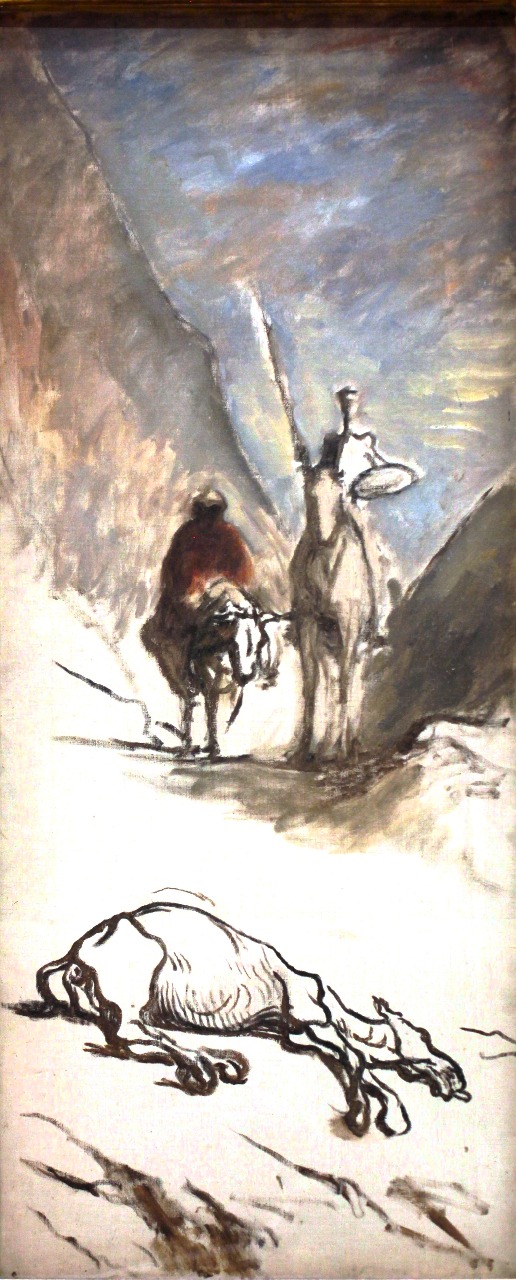

The fact that Daumier did not devote himself so much to classical literature, but was more of a habitué of the theatre, opera, circus and market jesters, did not mean that he lacked literary interests and next to the great illustrator Gustave Doré he became the one who, in my opinion, was best able to empathize with Don Quixote. Consider, for example, how the befuddled knight charges to attack one of his many chimeras, while his faithful friend and confidant Sancho Panza in despair raises his hands to the sky.

The same Sancho who, with respect and affection, follows his incomprehensibly idealistic master through one adventure after another. The great Don Quixote, always as sitting erect and proud on his frail Rosinante and equipped with his pitiful armour.

Sancho is sleeping soundly while Don Quixote sits awake and gazes into a fantasy world into which Sancho cannot keep him company.

Among Daumier's many illustrations for Cervantes’ Don Quixote, we can also find his preparatory and sometimes unfinished illustrations. With distinctive lines, Daumier firmly evokes the confrontation of the two Spaniards with a dead mule. The perspective is original and perfect, as is the discreet colouring.

Or take the quickly sketched image of Don Quixote riding down a slope, this is exactly what it looks like when a horse with a rider moves downhill. The diagonal balance is outstanding with Quixote's sharp profile and the angle of the lance creating a perfect triangle.

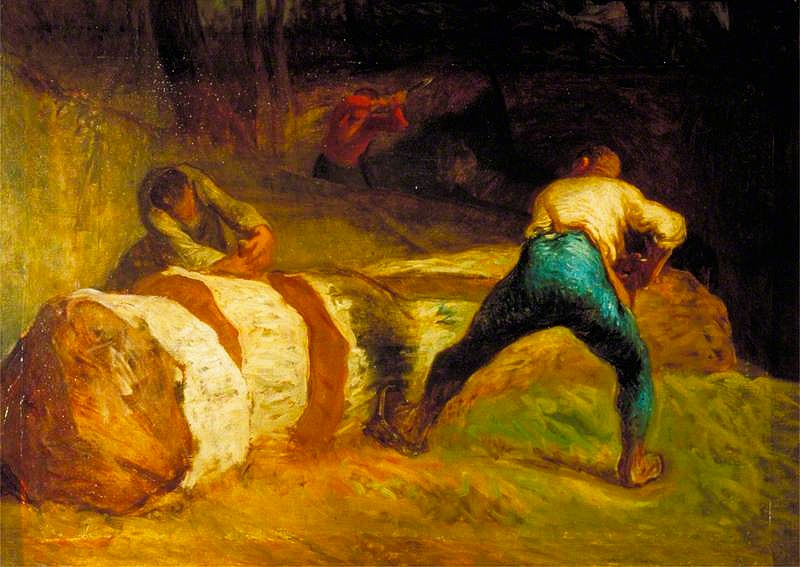

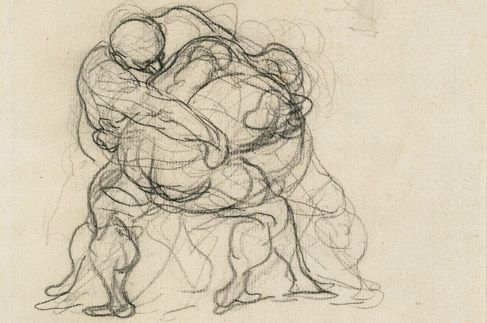

Daumier's linework is not always as distinct like that. He might also create figures through a jumble of lines. Consider this sketch of a pair of wrestlers, it certainly has a dynamic, an almost musical rhythm.

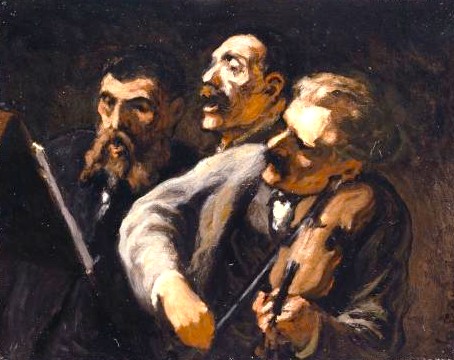

I have often found this rhythm within in Daumier’s art, here he actually depicts a musical moment, filled with his uncanny dynamism:

Movement and dynamics fascinated Daumier, as in this oil sketch where he depicted a man pulling himself down a rope.

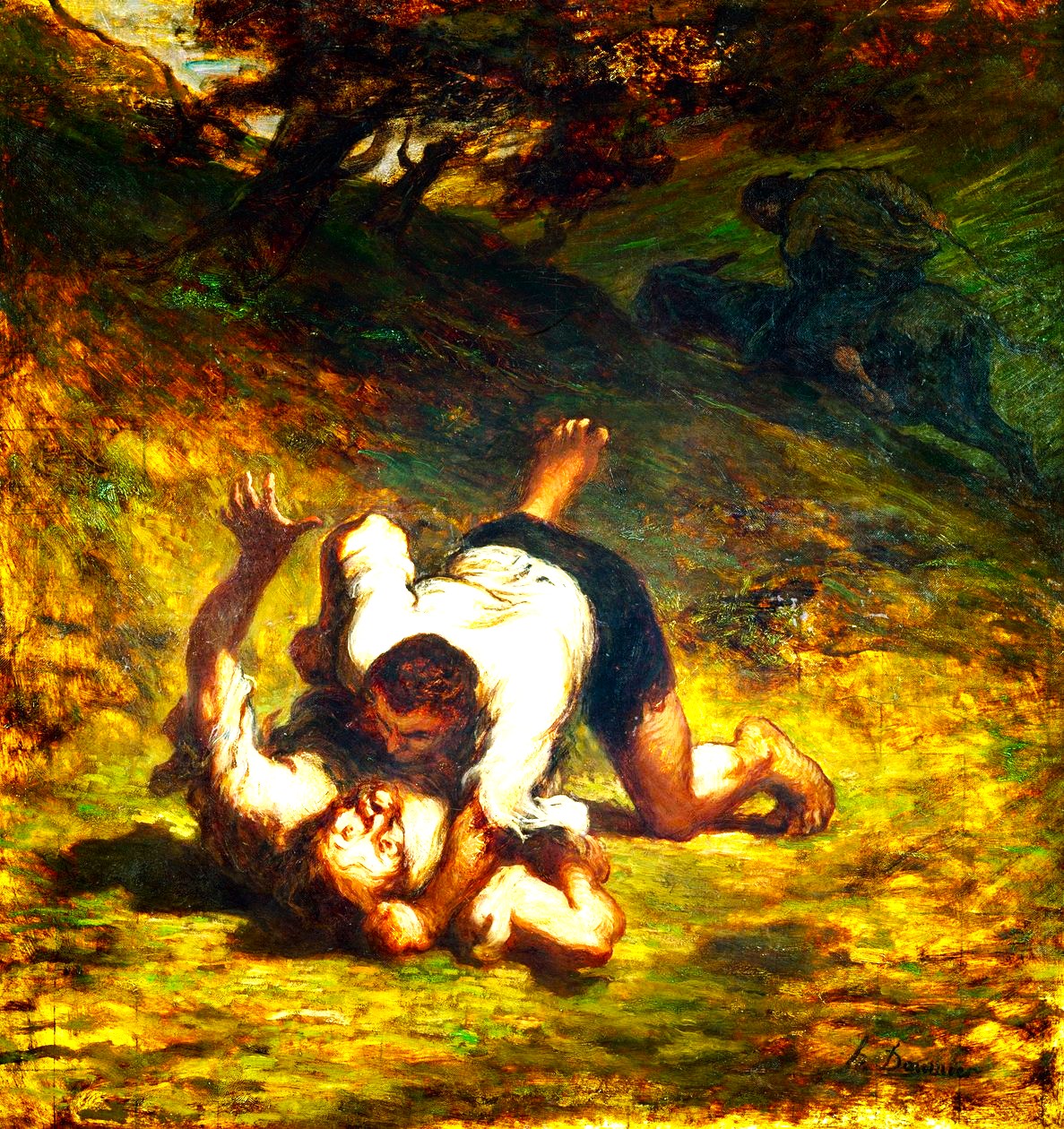

All the time this sharp gaze, this empathy. Another dynamic sketch also depicts two men wrestling, but here is a furious rage that was missing in the previous fight.

The oil painting that resulted from that sketch has retained, perhaps even amplified, the blind fury. The combatants are locked in a life-and-death struggle, while a third person in the background appears to be stealing a donkey from one of them.

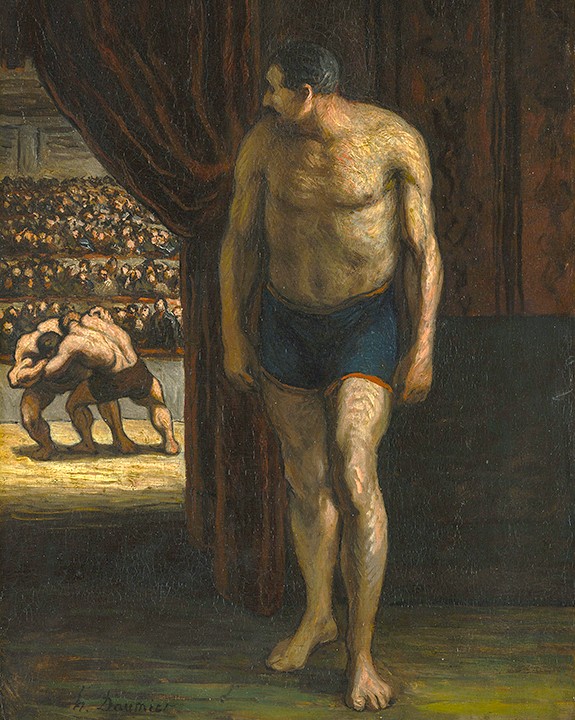

The wrestlers in the first sketch are professional fighters, and the painting they are based on I saw several years ago at Ordrupgaard in Charlottenlund outside Copenhagen, an art museum founded by the insurance firm owner, art collector, and millionaire Wilhelm Hansen. I visit this museum again after the world-famous Zaha Hadid in 2005 designed a light and airy exhibition space.

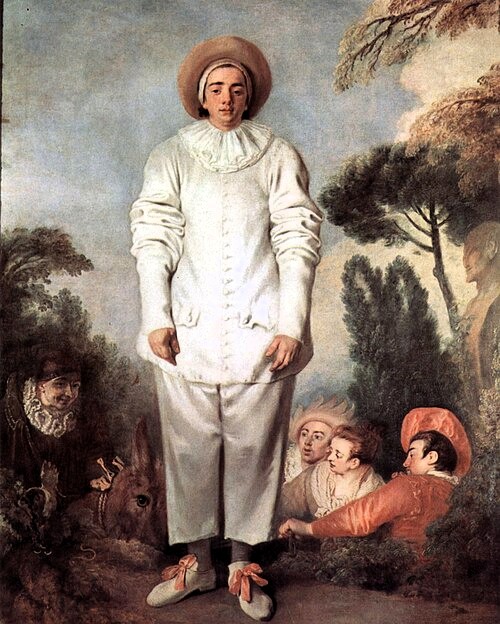

It is always a special feeling to end up in front of an original work of art and perhaps because I had that lithograph I mentioned above by my bed, I was particularly fascinated by Daumier's strongman waiting behind a curtain for his entrance in the circus ring. He looks towards the powerful wrestlers who are engaged in their fight. The lone pugilist does not convey strength and power, but rather vulnerability and loneliness, like Pierrot in Watteau’s famous eighteenth-century painting.

Market people, artists and jesters were Daumier’s soul mates, not lawyers, politicians and military men. He discovered the artistry in unassuming musicians, actors and chess players. Daumier’s market announcers are professional actors just like his cheating lawyers, but their artistry is art for art’s sake, not an act before an unsuspecting audience, or a humiliating, servile submission before some corrupt ruler.

Sometimes Daumier’s actors wear a mask, but it doesn’t hide any cheating and corruption. His circus folks exaggerate and try to attract their audience, but they don't hurt anyone. They lie, but the lie is part of the act, the make-believe, the entertainment, the audience is well aware of the lie, its part of the amusement.

People shout, sing, play and scream, but in all the commotion there is an authenticity that reveals what it's all about – simple joy and entertainment.

Daumier's art is also genuine. Not only in its fearlessness, its direct expression, its straightforward political stance, its depiction of life as it is, but also in its technique. He paints in a way that makes his viewers understand that what we see is art, "a part of a landscape seen through a temperament", not a photographic account where the brushstrokes have been hidden. At times, Daumier is so straightforward that his thick brushstrokes might bring to mind an abstract painting.

But the jumble of white lines, grey background and skin tones becomes a rhythmic whole that depicts how a Pierrot tunes his mandolin.

Does Daumier have no predecessors? He is certainly unique; lithography was a relatively new technology so he was in many ways a pioneer. When it came to his paintings and sketches, we find examples of contemporary predecessors, such as the slightly younger Millet and the slightly older Delacroix, who sometimes come close to Daumier.

When it comes to older masters, he may have been influenced by Rembrandt’s brown, black and golden chiaroscuro.

Daimier reminds me of the Genovese painter Alessandro Magnasco (1667–1795) both when it comes to the palette as the dynamic brushstrokes.

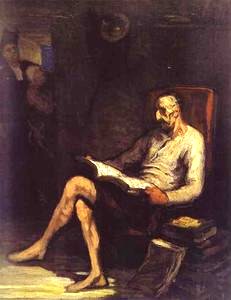

Daumier’s Don Quixote Reading, seem to evidence associations to Magnasco.

Perhaps he had seen the Magnasco paintings in the Louvre, for example the one depicting a gypsy wedding.

Nevertheless, to me Daumier is and remains unique, not least because for the many years I had his lithograph above my bed and often looked at the pale, helpless, and obviously poor girl in front of her judges. One of whom kept looking straight at me. Under the picture Daumier had written Huis clos – Behind closed doors.

Mandel, Gabriele (1971) L’Opera pittorica completa di Daumier. Milano: Rizzoli editore. Ramus, Charles F. (1978) Daumier: 120 Great Litographs. Garden City, New York: Dover Art Books

.jpg)