MEDEA, CHILD MURDERER AND FEMINIST ICON

After 23 months of war in Gaza, Save the Children estimated that the number of children killed exceeded 20,000. However, this does not mean that Israel's supreme war leader, Benjamin Netanyahu, is primarily regarded as a child murderer – nor is Heinrich Himmler, the supreme leader of the Second World War's systematic extermination of "undesirable population elements," which led to the annihilation of more than 1.5 million children.

Himmler had expressly ordered the liquidation of all Jewish children. In a speech in Posen (now Polish Posznań), on October 4, 1943, the unusually abominable Himmler had stated that not only Jewish men, but also Jewish women and children must be slaughtered:

For I did not consider myself justified in exterminating the men—in other words, killing them or having them killed—and then allowing their children to grow up to wreak vengeance on our children and grandchildren. The difficult decision had to be taken to make these people disappear from the face of the earth. For the organization that had to carry out this duty it was the most difficult that we have ever had to undertake.

However, the archetype of a pathological child killer is not Heinrich Himmler, but the mythical Medea who, in cold blood, murdered two of her children to avenge her husband's infidelity.

So it is a question of proportions. Like when the womanizer, mass murderer and marriage imposter Monsieur Verdoux defended himself in Chaplin's film of the same name:

Wars, conflict - it's all business. One murder makes a villain; millions, a hero. Numbers sanctify, my good fellow!

In fact, the cynical Verdoux quotes the English bishop Belby Porteus (1731-1809), a fierce opponent of the Church's hypocritical silence on, or even the defence of, the slave trade, which, according to him, was sanctified by greed. Profits even silence the Church and Mammon gags Jesus.

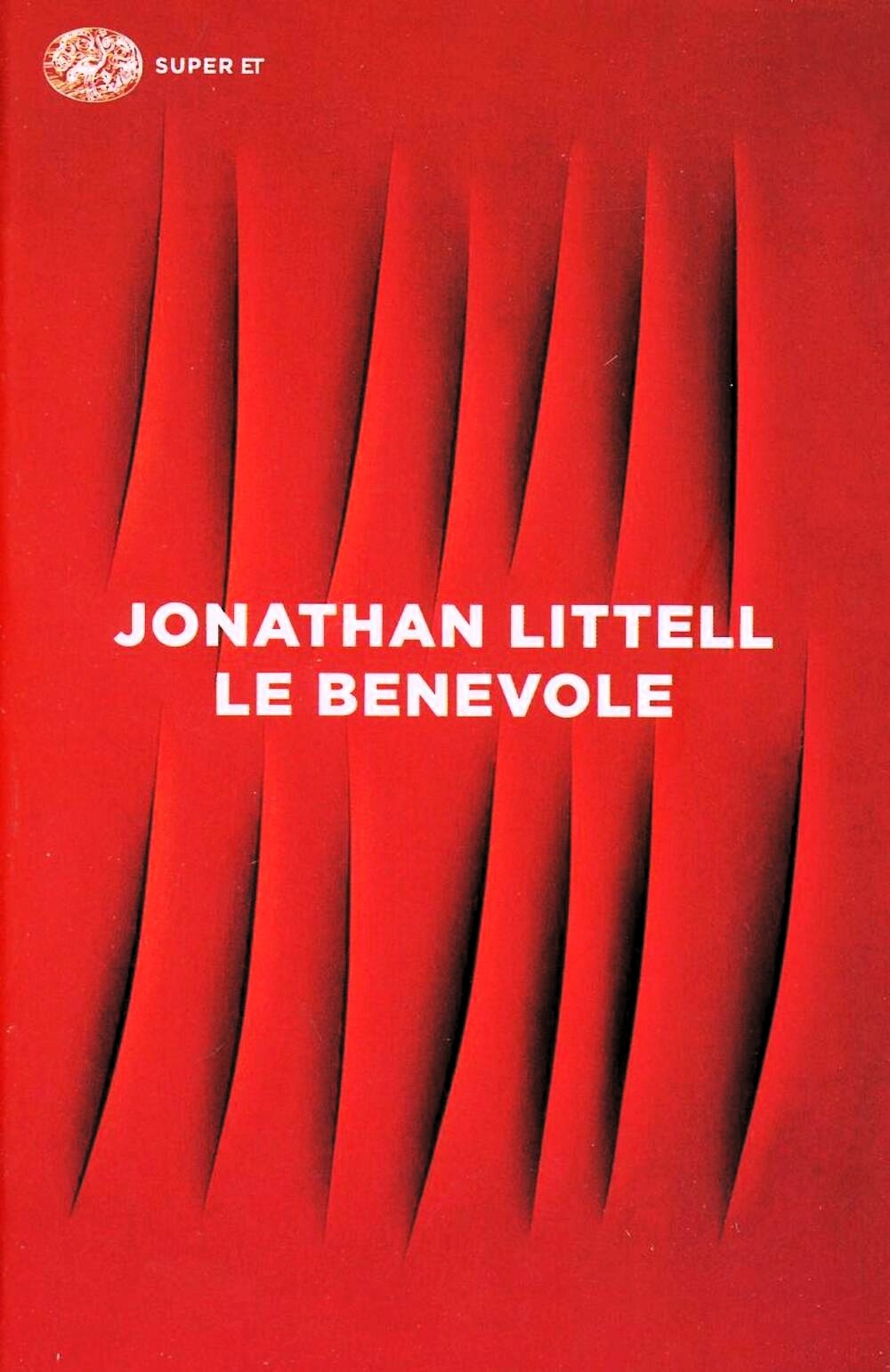

The absurdity of the dimensions of the murder is underlined in Jonhatan Littell's novel The Kindly Ones from 2006, in which the fictional SS officer Max Aue, without any apparent remorse, tells of his participation in the murders of Jews when he was an officer in the Sonder Commandos that liquidated Jews, partisans and gypsies on the Eastern Front and how he later became part of the organization of the concentration camps. This mass murderer gets into trouble not because of his participation in mass murder, which was rewarded with the Iron Cross, but because he was suspected on uncertain grounds of the murder of his mother and stepfather. Max Aue was therefore followed on his heels during the burning World War by two detective policemen from Kripo, the Nazi Kriminalpolizei. Kripo was mostly investigating crimes such as murder, rape and arson.

The title of the novel – Les Bienveillantes alludes to the ancient Greek theatrical trilogy Orestien by Aeschylus, in which Orestes, after murdering his mother, is hunted by the goddesses of vengeance, the Erinyes, but who is eventually exonerated in a trial, after which the Erinyes came to be called the Eumenids, the Benevolent. Max Aue is acquitted of the suspicion of his mother's murder, while his mass murders in the service of the Nazi regime are swept under the carpet.

The title of Littell's novel and its underlying Greek mythology bring us into the world of classical tragedy and one of its most fascinating characters – the child murderer Medea. She has followed me ever since we read Euripide’s drama at university. It was almost a shock to find how an author more than four hundred years before our era could have created such a passionate, insightful and multi-layered drama about a woman's anxiety and incredible crimes. How can a mother be driven to kill her own children? The drama is so rich and remarkable that I have read it several times, always in amazement.

Medea's story begins with a journey that dates back to the Bronze Age, perhaps around 1,300 BCE. The greatest heroes of the Greeks, several of them sons of gods and later fathers of several heroes of the Iliad, had joined the young Jason to sail with him to Colchis, located at the far end of the world known to the Greeks at the time. Specifically, on the coast of present-day Georgia, below the vast, snow-capped mountain massif of the Caucasus. There, in a grove in Kolchis hung the Golden Fleece, for unknown reasons coveted by the entire known world.

Far away, in the city of Iolchis in Greek Thessaly, King Pelias had usurped power after throwing his half-brother Aison into prison. In good time, however, Aison had sent his son Jason to be raised far out in the countryside by the wise centaur Cheiron.

When Jason as an adult left Cheiron and sought out Iolchi's, he ended up at a party organized by his sneaky uncle. When he saw the handsome youth, Pelias understood that it must be Jason, the rightful holder of his throne, but Pelias also realized that he could not kill his popular nephew and decided instead to send him on what he considered to be an impossible and deadly adventure – namely, the theft of the Golden Fleece.

This treasure found its origin when the sea god Poseidon coveted the beautiful Theophane. In order to seize the lovable creature all for himself and prevent her from falling into the hands of other lovers, Poseidon turned the poor girl into a ewe and himself into a ram. Their remarkable offspring became Chrysomallos, a huge ram that could fly and speak, and had a fur coat of gold, which shone like the sun. The amazing animal was given by Poseidon to the sun god Helios.

Nefele, a nymph linked to cloud formation and thus also had something to do with Helios, was married to king Athamas, with whom she had a boy and a girl, Phrixos and Helle. However, Athamas grew tired of Nefele, made her his concubine (something Jason much later wanted to do with Medea) and instead married Ino, whom Hera disliked because she had once saved the newborn Dionysus (the result of one of her husband Zeus' extramarital escapades) from her wrath.

Ino hated Nefele and falsely convinced her husband Athamas that she was behind a famine and that in order for the gods to be appeased, he had to sacrifice Phrixos and Helle. However, Nefele managed to tear his children away from her enraged ex-husband, who was about to lay his children on the altar and cut their throats.

From his heavenly heights, Helios had witnessed the drama and sent his golden Chrysomallos to earth that the children of Nephele might be brought to safety at the end of the world, i.e. Colchis. During their journey, however, Helle was seized by vertigo and fell into the strait that came to be known as the Hellespont after her.

Phrixos survived the perilous journey and sacrificed Chrysomallos to Zeus, because the supreme god in the form of Zeus Phýxius was the protector of refugees and strangers. Phrixos gave Chrysomallo's golden fleece to Colchi's king Aïtes, who was the son of Helios. In gratitude, Aïtes guaranteed Phrixos his protection and allowed him to marry his daughter Chalciope.

But why did Pelias send his nephew to retrieve the Golden Fleece? And the more difficult question – why did so many of Greece's greatest heroes accompany him on the perilous journey in search of a more or less incomprehensible object?

Like so many myths and fairy tales lost in ancient darkness, there are no proper answers to such questions, but that has not stopped a multitude of writers from trying to find answers to them. Before I tell about Medea, it might be enlightening to touch upon the issue of legendary quests

First, the fairy tale motif. All over the world, we find fixed patterns when it comes to the telling legends and myths. It is extremely common for young men, and sometimes the occasional woman, to set out in search of unknown places and things – Soria Moria Castle east of the sun and west of the moon, the Cave of Venus, El Dorado, the Holy Grail, the Philosopher's Stone, or the Herb of Life.

It can also be a story that symbolically depicts a young person's change into maturity. The heroes of these myths are, as mentioned, often young men who through their perilous journeys come to an understanding of what life is really about, or more often than not, they find a woman with whom they can share their life and have children. Or – perhaps it is a matter of following a destiny that higher powers have already determined for them.

For Jason, perhaps the hunt for the Golden Fleece was a combination of all of that – he sought a mysterious object that he finally obtained by overcoming a monster and brought back with him a beautiful woman, at the same time, he had with her help been able to accomplish a mission set about by Hera – that of marriage, fidelity and home, after all she was the goddess of home and maternal love. When Jason finally broke these sanctified conditions, he got really bad off, but at first – Hera had been gracious to him.

Hera had made plans for how to exact revenge on the Pelias, who was hated by her. He had on a number of occasions denied her the sacrifices that were due to her and, even worse, had murdered a woman within her temple.

Pelia's mother had been displaced by his father (apparently a common behavior among Greek kings) and remained living as a concubine in the house of King Salmoneo. However, the king's new wife, Sidero, treated her predecessor and her son so badly that, after he became an adult, the latter attacked his wicked stepmother so violently that she had to seek refuge in the temple of Hera. The enraged Pelias did not allow himself to be hindered by the fact that his so hated stepmother had sought Hera's protection, but rushed after Sidero into the temple and stabbed her to death in front the altar dedicated to Hera, thereby irreparably defiling the sanctuary of the goddess.

When Hera heard that Pelias was again arranging a great sacrifice to the gods, but one more intended to omit her, the goddess changed herself into an old, broken woman, and sat herself down at a crossroads outside the city of Iolchis, asked passers-by to carry her across a swift running stream. This was the goddess's way of finding someone worthy of her trust.

Passers-by ignored the disguised Hera's request for help until Jason appeared and carried her across the river. Hera realized that this handsome young man was to be trusted. However, one of Jason's sandals had been stuck in the river, and when he later showed up at Pylia's sacrificial ceremony, Pylias was horrified to notice that he was missing a sandal. The despotic ruler had namely been prophesied that a young man wearing only one sandal would eventually cause his death, and what was worse – when asked who he was, Jason replied:

Having now reached the age of twenty without having previously uttered any insults or committed deplorable acts, I have come home to restore my father's former honour and to reclaim the royal title that others have usurped.

The terrified Pylias promised Jason to have the best possible ship built, lavishly equipped, and man it with Greece's most intrepid youths, not least the great Heracles, so that Jason could thus would be able to conquer the Golden Fleece and prove himself worthy of Iolchi's royal throne.

This was a test of manhood that caused by the fact that Jason had been wearing only one sandal, a sign that he only had one foot on the ground and found himself in an intermediate stage, halfway between youth and maturity. The great adventure would make Jason a real man, someone who had proved his strength and courage.

It was the poet Pindar (518 – 438 f.Kr) who had narrated this in an ode he sang during the Olympic Games in 466 BCE. In the ode, Pindar also paid tribute to Medea, whom he made sing about the voyage of the ship Argos:

Thus sounded Medea's rhythmic song, and in immovable silence the godlike heroes bowed their heads as they listened to her wise counsel.

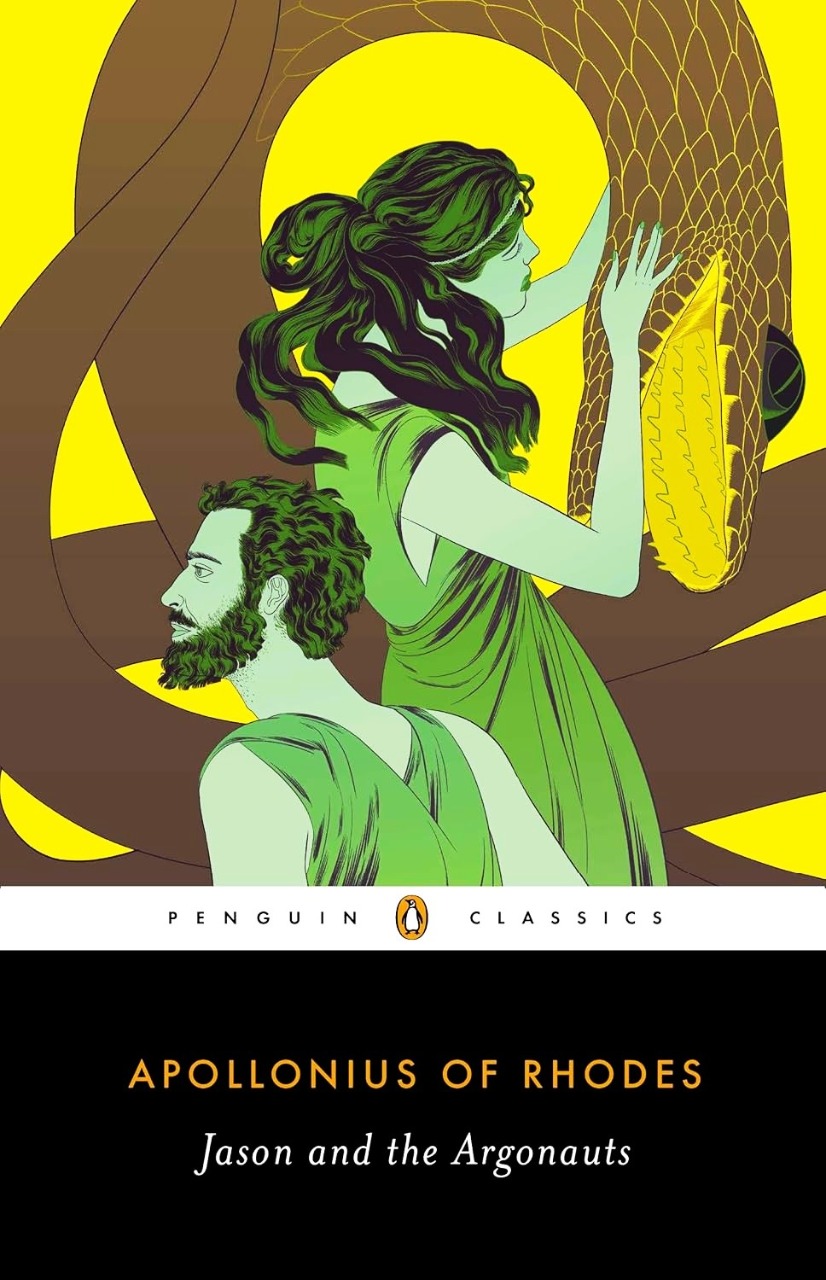

Pindar’s stanzas were part of the first longer account of the Argonauts' journey to Iolchis, though Apollonius of Rhodes (295 – 215 f.Kr.) Argonautica became the classic account of their adventures, dramatic and well-written in artful Greek by a librarian at the huge library of Alexandria, where he had access to the large number of heroic tales and geographical depictions that came to form the basis of his story.

Medea is the person who stands out most sharply and the reader gets to follow her thoughts and feelings through inner monologues. The other characters of this fanciful fairy tale, including Jason, are far more standardized depictions. Argonautica is a classic adventure story, filled with excitement and romance.

The stately ship Argos was by the master builder Argus created under the direction of the goddess Athena. Argus then accompanied Jason on his journey. Argos was timbered from spruce and its fifty oars were made from pines cut at the sacred Mount Pelion. In the bow, Argus hammered a branch from a sacred oak growing in the grove of Zeus in Dodona, where the trees could speak. The branch had the ability to speak in times of danger and then advise Jason on what to do.

It was time to leave. The men and women of Iolchis gathered together to bid farewell in admiration, weeping, and lamentation to this formidable gathering of Greece's most beloved idols, all stately young men, spectacularly dressed in armour and exquisite cloaks walking down to the Argo, the most magnificent ship ever built in Greece. With exquisite eloquence, Jason comforted his loved ones, but as he walked down to the waiting ship in celebration, he barely noticed

Iphias, the aged priestess of Artemis, their City’s guardian, who came forward and kissed his right hand, but was unable for all her eagerness to say a word to him as the crowd swept on. She was left there by the roadside, as the old are left by the young. Jason had passed and soon was out of sight.

One of the many exquisite scenes that Apollonius provides with, sometimes, as here, with a discreet, sensible commentary.

The young fighters boarded the ship and placed themselves on their predestined places on the rowing benches, when the Argos had reached open water the huge sail was stretched by a gentle breeze and the adventure began.

They sailed north and then followed the southern coast of the Black Sea towards Colchis, but it was not only a journey through real shipping lanes but also through the enchanted world of myths. The Argonauts fought hostile armies, six-armed monsters and flying harpies, sailed between insidiously wandering cliffs, shipmates were abducted by water nymphs, or fell victims to huge wild boars with poisonous bites, hideous eagles shot deadly feathers at them.

On several occasions, the men's patience seemed to be running out, and they wished for nothing more than to return home. But Jason's eloquence and firm conviction that they would succeed in conquering the Golden Fleece and thus everlasting glory, managed to convince the crew that it would be unwise to return when they had come so far and put up with so much.

A shore attack with future consequences, that was not told by Apollonius, but was preserved in a number of legends, was when King Laomedon of Troy asked Heracles and Jason to kill a Chetus, a kind of huge sea monster, which was tormenting the inhabitants of his city. Heracles killed the monster, but Laomedon denied the Argonauts their rightful reward. The result was that Heracles and Jason later returned and plundered Troy. When a huge Greek army several years later fought the Trojans, something that is told in detail in the Iliad, it is told that Jason and Heracles were among the fighters.

This is according to medieval chansons gestes, songs of glorious deeds, – in fact, both Jason and Heracles were far too old to participate in the Trojan War and legends about them seem to be older than those told about the Trojan War. The deeds of Heracles are often mentioned in the Iliad, but already there they have become fairy tales.

The Iliad also mentions Jason, but only as a famous "seafarer", father of the king of Lemnos. In medieval chansons , however, Jason's love story with Medea is highlighted and Heracles has become a mighty hero who in the battles of Troy even overshadows Achilles. At the end of the siege of Troy, Heracles hacks his way through the warlike turmoil with his huge sword until he meets Laomedon and with a stab makes his head fly over the violently fighting warriors.

With Apollonius of Rhodes, Jason is not a complete hero, he is equipped with shortcomings and human weaknesses. At times, Jason had considerable difficulties in asserting himself among his equally strong and often more experienced followers. Often he had to confirm his leadership with the support of the seers and respected mediators who had come along for the adventure, not to mention Zeus’ speaking branch nailed to Argos bow, as well as ever-emerging gods and other mythical beings.

At first, Jason seemed to be bothered by being in the shadow of the mighty son of Zeus, Heracles, who even before he joined the Argonauts was widely famous and had been travelling through the kingdoms they arrived at during their journey. Before leaving, Jason had let the Argos crew vote on who they wanted to be their leader and the choice had then fallen unanimously on Heracles, who declined with the reference that it was actually Jason who had been given the task of conquering the Golden Fleece and thus chosen by gods and humans to lead them, despite his youth.

When Heracles' young friend, lover and squire, Hylas, was abducted by water nymphs, and Heracles beside himself and filled with concern for his friend, desperately and furiously lost himself in the forests, Argos' helmsman, Tiphys, requested that they had to take advantage of the fair winds and interrupt their search and waiting for Heracles. Jason agreed with him, However, once out at the open sea, his crew raged against Jason, demanding a return to continue the search for Heracles. The hard-pressed Jason was once again asked for help from the gods, and as an answer to his prayer the gigantic, green sea creature Glaucus, appeared out of the depths, grabbing hold of the ship's railing and asserting to the terrified men that Jason had the full support of the gods. A relieved and much more animated Jason could then take a more secure grip on his commanding power.

Apollonius occasionally lapses into marking only the places that the Argonauts pass through, or where they make their landings, by offering brief notes on the myths and topography that had been associated with them. Occasionally, however, the drama took the form more detailed descriptions of exciting and strange events. Like the meeting with Phineas, a seer who had preferred a long life instead of sight and therefore had been blinded by the gods, though blessed with a profound knowledge of the future. For example, he had told Phrixos that he should let the golden ram Chrysomallos carry him to Cholcis. But Phineas could not refrain himself from telling the horrors that awaited even the gods, and also all of mankind. Zeus became annoyed by this sincerity, and thus punished Phineas, who could not see his own future, by allowing him to be tormented by the harpies, abominable flying beasts, half women, half vultures. As soon as he was about to eat, these monsters plunged down from heaven, ate what they could of Phineas' food, and defiled the rest.

The Argonauts' first sight of the starved, worn-out and blind Phineas is a good example of Apollonius' art of depiction:

He rose from bed, like a phantom in a dream, and with the aid of a staff crept to door on withered feet, feeling his way along the walls. Weakness and age made his limbs tremble as he walked; his shrivelled flesh was caked with dirt, and his bones were held together only by the skin. When he had come out from the hall, his knees gave way and he sat down on the threshold of the courtyard. And there he swooned. The ground beneath him seemed to reel; and he sank down in a coma without the power to speak or stir.

When Phineas had come to his senses and listened to the youthful voices of the Argonauts, he raised a desperate prayer to Zeus for the thousandth time begging him for mercy, and suddenly he saw in his mind's eye not his own future but that of the Argonauts, and understood that they had come to free him from the terrible harpies, which they also succeeded in doing. An overjoyed Phineas offered the Greeks a splendid banquet in gratitude and told the Argonauts of their future travel and what would happen to them next. Wise of the injury, however, he left out all the misery that would befall each of them. After that, Phineas, still blind, had a fairly fine life. However, he never died, but in due course turned into a mole.

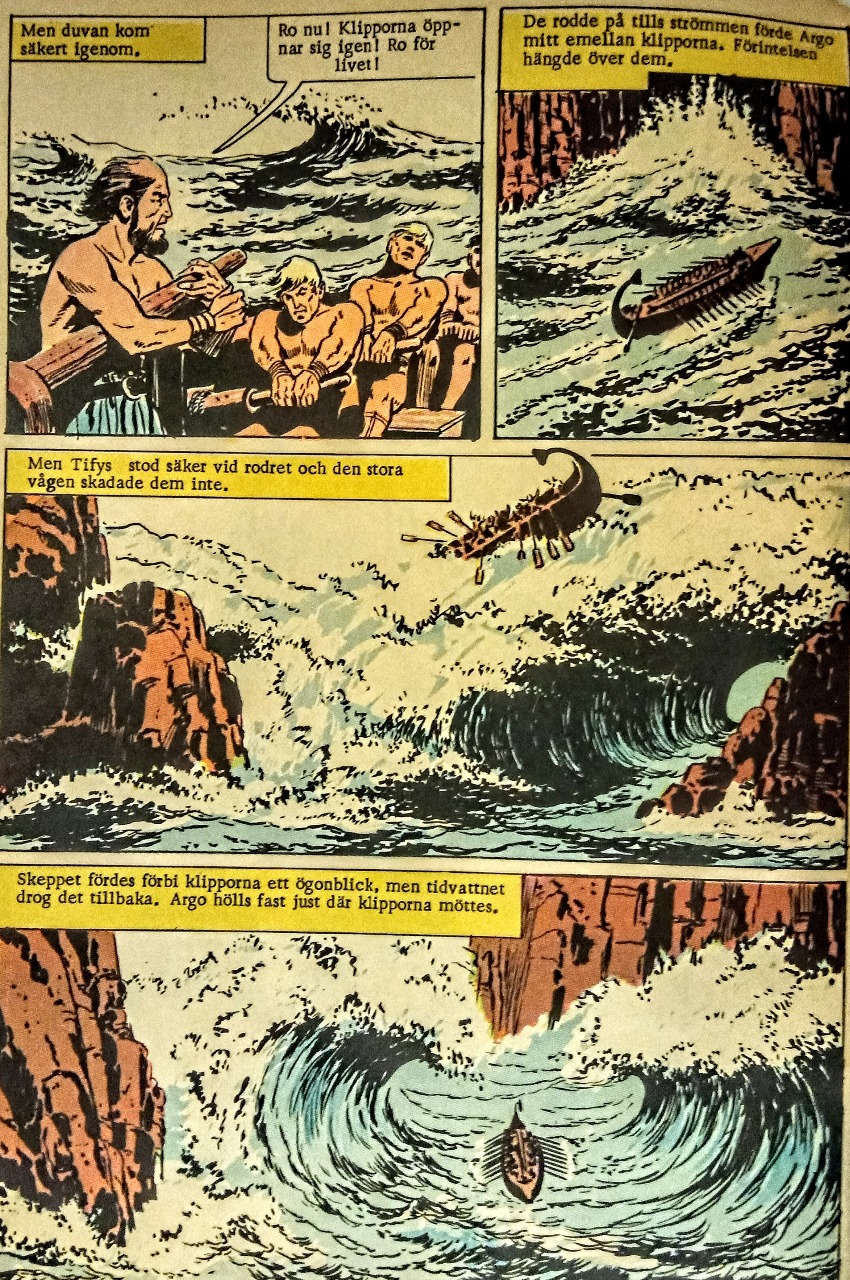

Phineas told how the Argonauts would get past the dreaded Clashing Rocks. Soaring cliffs that rose vertically into the sky without a foothold in the depths of the sea. Every ship had to pass them, and almost all of them were doomed to perish, but Phineas could give advice on how to get past them. He told the Argonauts how they would be able to escape being crushed and be carried past them by the treacherous currents produced by the rocks. The depiction of Argo's journey between the rocks is certainly dramatic.

Before the Argonauts had arrived at Phinea’s Island, Jason had committed a rather deplorable act, a premonition of his future betrayals. Before the Argonauts went ashore at the island of Lemnos its women had murdered all of their sybaritic husbands, who had become accustomed to living in the hustle and bustle of slave girls they had abducted during their wars. Their present queen, Hypsipyle, had, however, advised the women not to carry out their cruel revenge and had not herself taken part in the slaughter of the pitiful men. She had the women that after their bloody deed, they would be forced to perform the men's hard chores, such as plowing the hard soil, fishing on the treacherous sea, and caring for unruly cattle. On top of this hardy life, they would live in fear of being attacked by their neighbors – the warlike Thracians.

When the women a little over a year after the murders, sighted the approaching Argo, they feared that it was Thracians who would attack them. However, pleasantly surprised they found that the crew was handsome, friendly young men. Since Hypsipyle had previously advised her female subjects to conceal their crime and seek love from capable men, they now did everything possible to attach the Argonauts to them, and they succeeded beyond expectations.

The Argonauts decided to stay on the island and put the journey to Colchis out of their minds. Jason played along and seduced the beautiful Hypsipyle with false pretenses of a happy life together, although all the time he was focused on traveling on to Colchis after the pleasant stay at Lemnos.

When Hypsipyle became pregnant with what would turn out to be twins, Jason decided to abandon her and with a fiery speech he managed to get his men to follow him on towards Colchis. He alleviated Hypsipyle’s' grief by lofty promises of a speedy return, which turned out to be a lie, combining his promises with threats to expose the crimes of the Lemnian women.

The grieving Hypsipyle was by hope and love driven to believe in Jason and gave him as farewell present a god-given fantastic cloak, which Jason later passed on to Medea, who in the future used it to take the life of Jason’s new, young wife. For his crimes, Dante relegated Jason to a place in his Inferno:

The good master [Virgil, Dante's companion], though I have not asked,

said to me, "Look at him there, so tall,

who, despite his pain, does not seem to shed tears,

what a royal countenance he maintains!

That is Jason, through courage and wisdom,

from the Colchies took the golden fleece.

He came on this trip to the island of Lemnos

where cruel, bold women

to all his their had given death.

With beautiful speech and flattering signs

he deceived Hypsipyle, the maiden

whom had heated all fellow sisters.

There he left her, pregnant and alone;

for such a crime he is condemned to this torment [being constantly whipped by demons],

and even for Medea he is punished.

I do not have an English translation with me here, so I had to do a clumsy translation from Italian.

Finally, the Argonauts reach the destination of the journey – Colchis. If they had expected a miserable outpost by the end of the world, they were mistaken. They are greeted by a thriving city with an imposing palace of gold and marble over which the tough and powerful Aïtes, son of the Sun himself, Helios, rules with an iron grip.

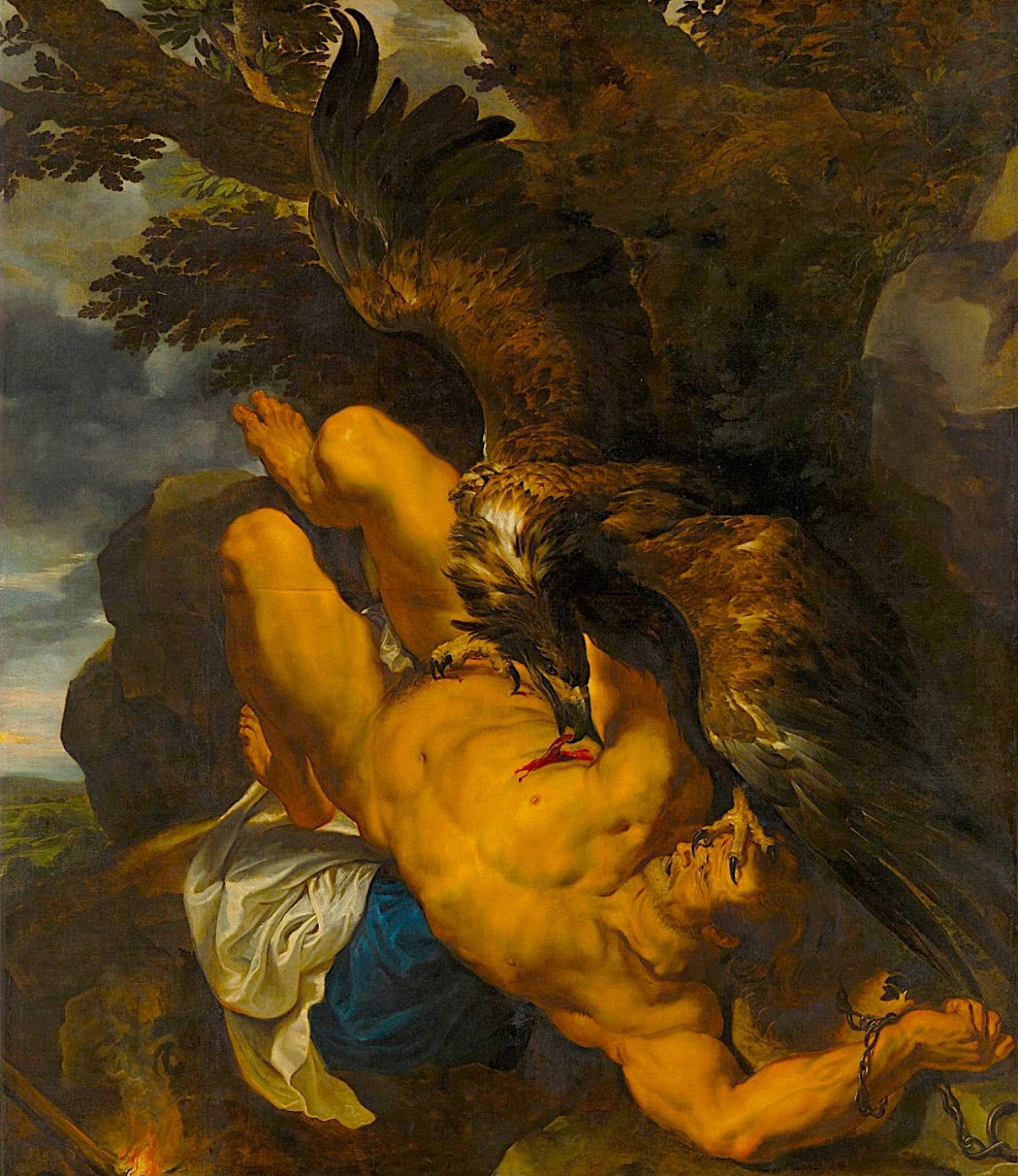

The surrounding landscape stunned the Argonauts, they had never seen mountains as high as those that crowned the impressive Caucasus mountain range. They knew that high up there Zeus had chained the mighty titan Prometheus, the benefactor of men, chained, while an eagle gobbled his liver every day, the liver was restored the next morning. The Titan's cry of pain gave the Argonauts a hint of hard trials that lay awaiting them.

And now the last recess of the Black Sea opened up and they caught sight of the high crags of Caucasus were Prometheus lied chained by every limb to the hard rock with fetters of bronze, and fed an eagle on his liver. The bird kept eagerly returning to its feed. They saw it in the afternoon flying high above the ship with a strident whirr. It was near the clouds, yet it made their canvas quiver to its wing as it beat by, for its form was not that of an ordinary bird: the long quill-fathers of each wing rose an fell like a bank of polished oars. Soon after the eagle had passed they heard Prometheus shriek in agony as it pecked his liver, the air rang with his screams till at length they saw the flesh-devouring bird fly back from the mountain by the same way as it came

It is in Colchis that the drama takes on a more human touch than before, the characters – especially Medea – take on a firmer form and character. Through Jason King Aïtes found out that the Argonauts were after his beloved Golden Fleece and he became furious. He had sworn never to lose the precious fur that had become one with the fame of his kingdom. Aïtes had nailed the Golden Fleece to the broad trunk of an oak consecrated to Zeus. No man could approach the treasure because it was guarded day and night by a gigantic serpent, whose long fangs dripped with deadly poison.

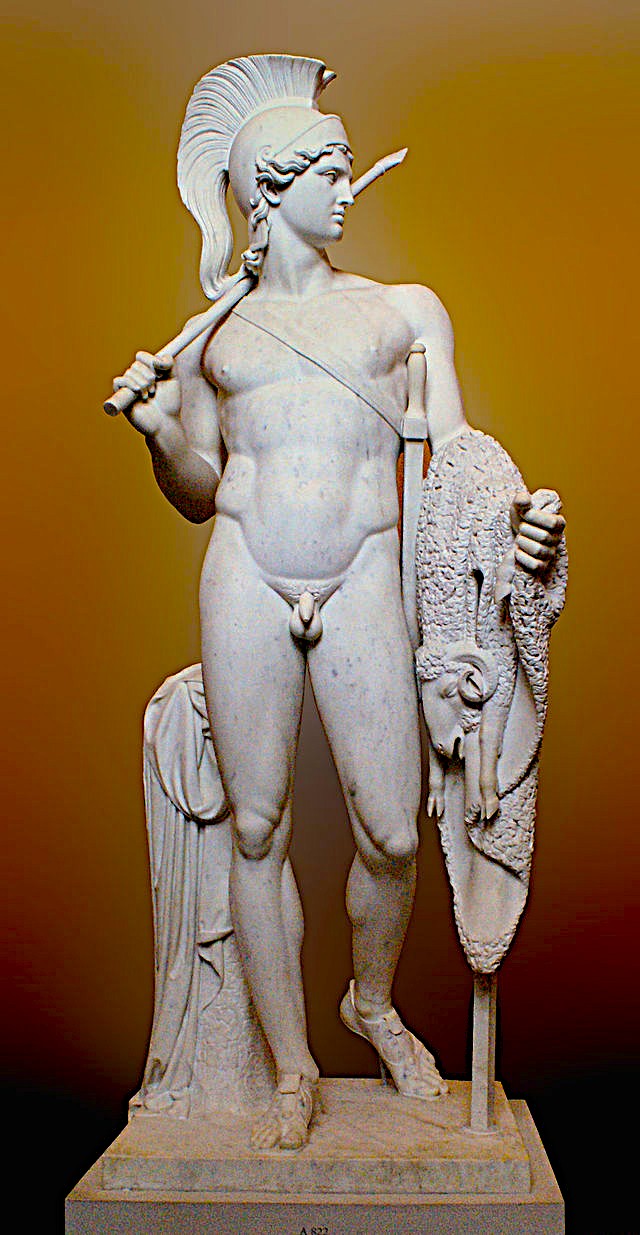

Aïte's fury was further heightened by Jason's offer to attack Colchi's enemies in exchange for the golden fur. What enemies could a king like Aïtes fear? If he needed an unbeatable army, he single-handedly sowed a field with the dragon's teeth that he, together with his kinsman Cadmos, had knocked out of the jaws of a dragon they had slain outside Corinth. Each time, the dragon sowing gave rise to an army of invincible warriors.

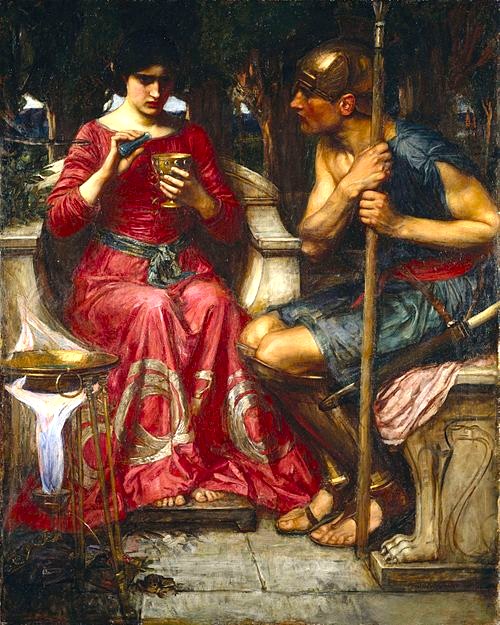

The goddess Hera knew this and together with her confidant goddess – Athena, who also was captivated by Jason’s charm and beauty, Hera went to the goddess of love, Aphrodite, and at the insistence of the goddesses Aphrodite agreed to send her mischievous son Eros to pierce Medea's heart with one of his arrows of love.

Medea had from her aunts Circe and Parsiphaë inherited the arts of magic, the good as well as the evil ones. Medea served as high priestess in the temple of Hecate. Like the great Apollo, the god of light and art, but also lord of plagues and rats, Hecate also had a dual nature. She was the goddess of healing herbs, health and security, but also of the unbridled, cruel Nature, of evil magic and dark powers.

Eros' arrow badly wounded Medea, who until then had been her father's most beloved child, faithful and obedient to him in everything. In addition, she was extraordinarily beautiful. Like her father and her aunts, she was endowed with the sun's piercing gaze and dazzling blondeness. This is despite the fact that she is generally portrayed as black-haired and exotically alluring.

When one of her handmaidens had informed Medea that handsome strangers from a distant land had sought out her father, she was seized by a disturbing premonition that her life would now be profoundly changed. Her connection to the dark forces of destiny made her realize that her fate was going to become connected to these strangers and that the future would bring nothing good.

And it got even worse when, at the first sight of Jason, she was simultaneously hit by Cupid's well-aimed arrow and struck by a violent desire for this divinely beautiful youth. As Ovid wrote in his Metamorphoses, Medea was already at the first sight of Jason hopelessly lost and helplessly captivated:

She fell deeply in love with the handsome Jason. Despite a long struggle against her feelings, her reason was powerless to master her passion: “It’s useless to fight Medea,” she said. “ Some God is against you. This or something akin to it surely, is what they call love. How else should I fear for the life of a man I have only just seen? – But why should I feel so afraid? How wretched I am! I must extinguish the fire which is raging inside my innocent heart. I should be more sane, if I could!

Jason had not been hit by any of Eros' arrows, though he understood that his only way to complete the hopeless mission assigned to him was to seek help, something he had often had done often during Argos' journey towards Colchis.

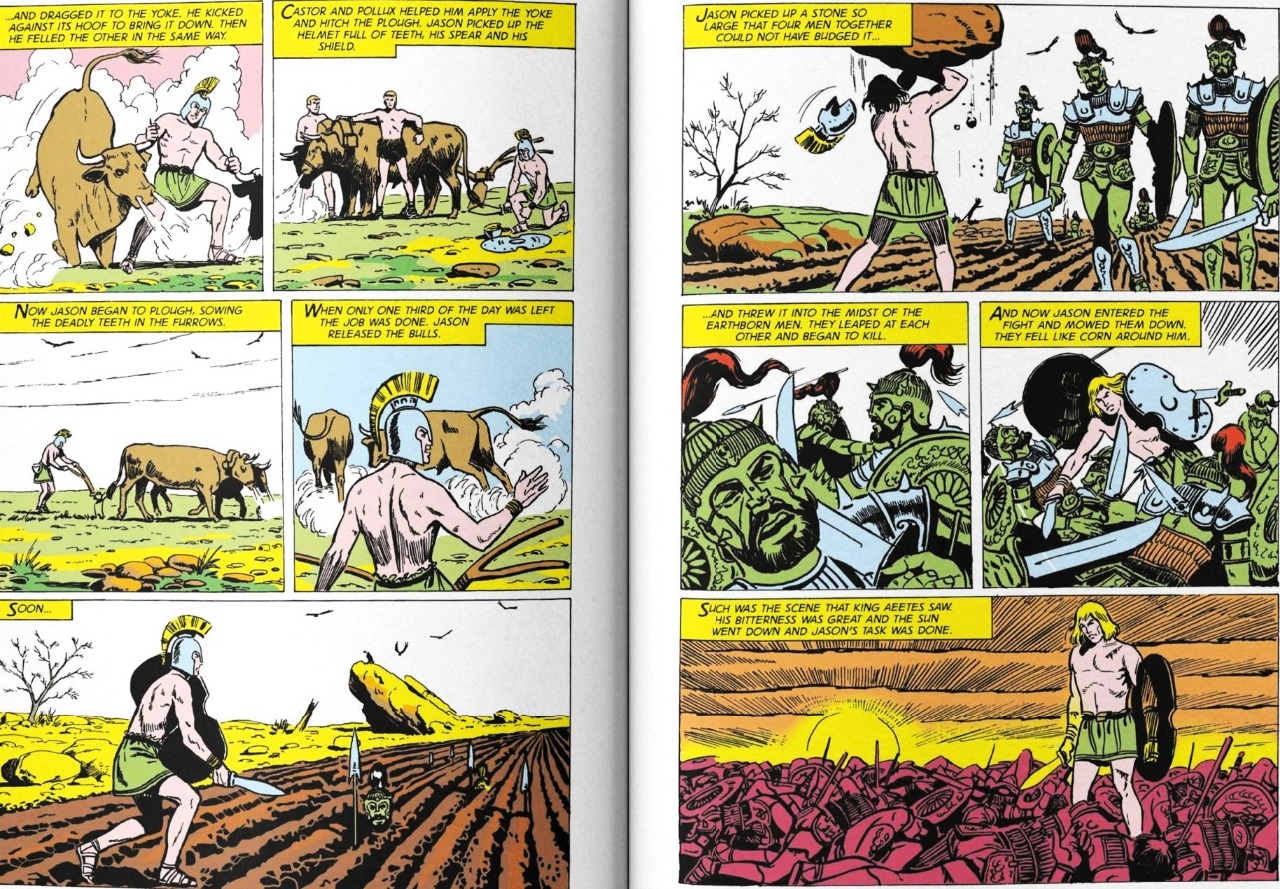

As in the world of fairy tales, Aïtes made a promise to Jason that he could receive the Golden Fleece as a gift if he could prove himself to be more than an ordinary person. Accordingly, Aïtes gave Jason three utterly impossible tasks – subdue the king's huge, fire-breathing bulls, equipped with deadly pointed bronze horns, then harness them in front of a heavy plough and plough a field while sowing it with dragon seed that would give rise to an army of demonic warriors. After defeating these bronze-clad demons of the Underworld, Jason must overcome the terrifying poisonous snake that tirelessly guarded the Golden Fleece. Only then would he be found worthy to lift the skin from its oak trunk and bring it back to Greece.

It was with great anxiety that the hopelessly love stricken Meda had listened to all this. She knew it was in her power to protect Jason from the dangers and make him to fulfill the assignments – but would she betray her father, her fatherland and help someone who was so hated by her father? A betrayal that would mean that she was no longer welcome among the Colchians.

Medea spent a sleepless night during which she repeatedly ran in to her sister Chalciope’s room, she had been married to Phrixus (it was whispered that he had been assassinated by the girls' despotic father) and thus knew how difficult it was to live with a stranger in one's own country. If Medea wanted to unite her fate with Jason, she had to leave Colchis.

Chalciope had been deeply in love with her Greek husband and understood her sister's dilemma. She advised her to help Jason and then flee with him to the mythical Greece, which her homesick husband Phrixus had praised in warm terms.

Medea decided to help Jason, but hesitated about fleeing from her homeland. After all, she was both attached to and feared her tyrannical father, Furthermore, she worried about a future as a stranger in a completely unfamiliar land. And... above all – she lived within what Eric Robertson Dodds has called a "pronounced culture of shame", according to him it was the fear of being shamed that characterized the Greeks' belief in their gods and their association with their fellow human beings – "What will everyone else think of me and my actions?" During her sleepmless night, Medea turned and twisted her painful thoughts:

Let him be killed in the struggle, if it is indeed his fate to die in the unploughed field. For how could I prepare the drug without my parent’s knowledge? What story shall I tell them? What trickery will serve? How can I help him, and fail to be found out? Are he and I to meet alone? Indeed, I am ill-starred, for even he dies, I have no hope of happiness; with Jason dead, I should taste real misery. Away with modesty, farewell to my good name! Saved from all harm by me, let him go where he please, and let me die, On the very day of his success I could hang myself from a rafter or take deadly poison. Yet even so my death would never save me from their wicked tongues.

Medea knew full well that only she, Circe's granddaughter and Hecate's priestess, was the only one capable of producing the ointment of invulnerability that would make Jason powerful and indestructible. Through her wizardry, Jason would be able to harness the fire-breathing bulls in front of the plow, plow the field, sow the dragon's teeth, and defeat the demon warriors. And then – then he would have stolen the fleece and sailed away across the seas, leaving Medea behind, alone with the shame of having betrayed her father and her country.

Meda had not even spoken to Jason, and therefore decided to seek him out before dawn, where Argo lay hidden in the high reeds of a viscous river outside the city.

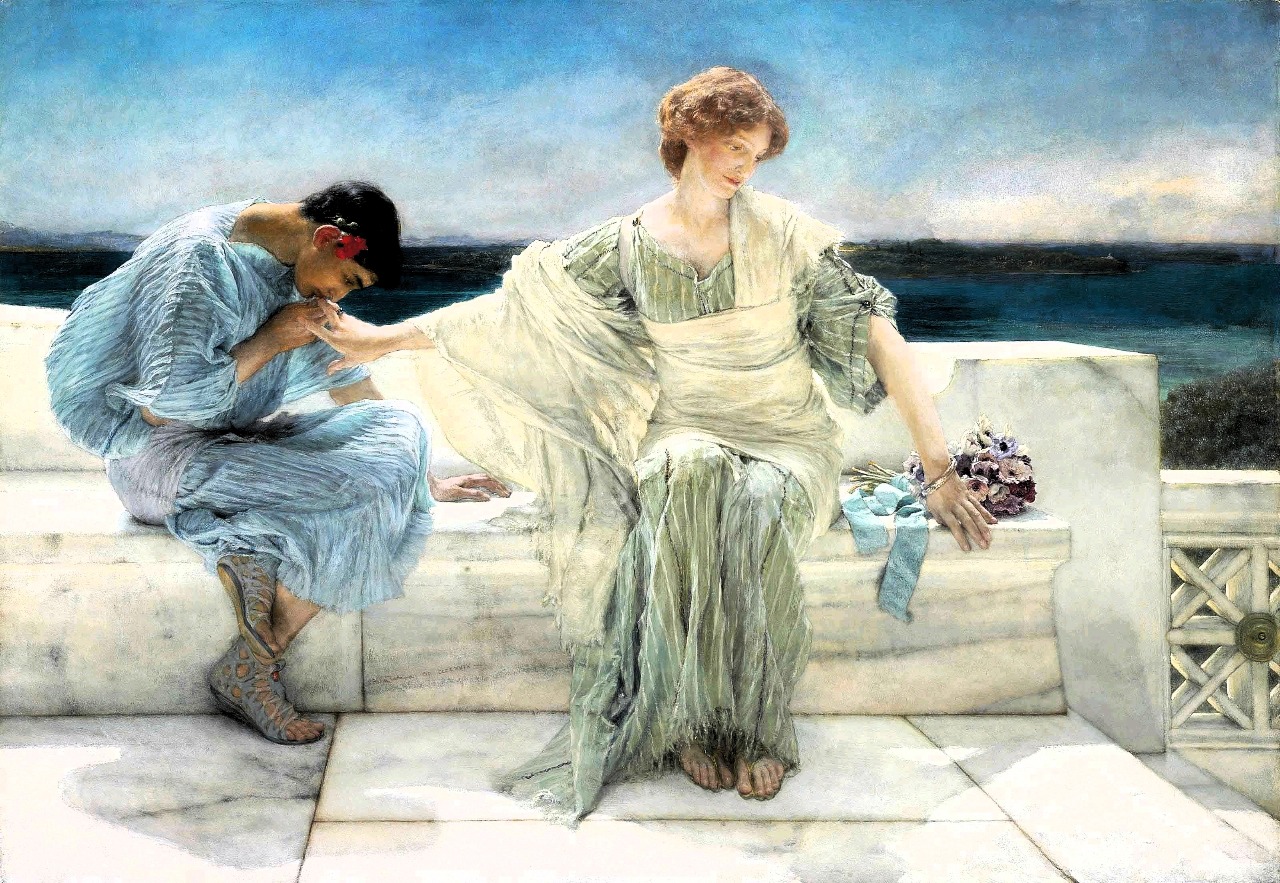

When she had left her handmaidens behind and met Jason at a place she had agreed to with his emissary, one of Phrixus's sons who had joined Jason's men, Jason was dazzled by how Medea's beauty shone in the moonlight, she was not for nothing the granddaughter of the sun. Medea, however, was more captivated than Jason:

At one moment both of them were staring at the ground in deep embarrassment: at the next they were smiling and glancing at each other with the love-light in their eyes. […] Tears of agony ran down her cheeks and her whole body was possessed by agony, a searing pain which shot along her nerves and deep into the nape of her neck, that vulnerable spot where the relentless archery of love causes the keenest pangs.

Already knowing that he could benefit from the beautiful girl's knowledge, Jason let his eloquence flow freely. He compared Medea to the most beautiful goddesses imaginable, professed his eternal love, and promised to take her with him on the journey back to his land – more beautiful and more cultured than this godforsaken Colchis at the end of the world. Medea was helplessly seduced, dazzled, blind and captivated. Ovid related the prodigious moment:

Aeson's son looked more beautiful than ever. Medea could hardly be blamed for her passion. Her gaze was fixed on his face, as if she had never seen it before. "There must be a god standing there," she thought in her madness, unable to turn away. But when the stranger had begun to speak, and suddenly seized her right hand, and in the humblest voice begged for her help, promising to make her his wife, Medea burst into tears and answered: "I know what I am doing: so if I am deceived, I cannot blame my ignorance, only my love. You should have your life to thank for the help I give you. Make sure you keep your promise!" He swore by the rites of the threefold goddess [Hekate] and all the power that was hidden in the sacred grove [in which they were]; he swore by his father-to-be, the all-seeing sun-god [Helios], of all the successes he hoped for and all the dangers he feared. Medea believed him.

While judging Medea’s horrible deeds let us keep in mind that she is portrayed as an extremely intelligent, thoughtful woman. Someone who carefully considers every action, every step she takes. Her name seems to be related to the Greek medéia, "anticipate, plan, think through", but this did not prevent her from occasionally succumbing to violent passions.

Here we can once again take Dodds to help. The inner painful conversations that Medea occasionally engaged in, and which in Euripides and Seneca became effective monologs, can be explained by the Greek concepts of the soul psyche and thumos. Psyche can might be regarded as a person's personality/character, her social/disciplined self. Thumos, on the other hand, is linked to the body, its functions and thus also to various desires such as hunger and sleep, but not least different urges such as sexual drive, or anger when it takes on bodily expressions, such as physical violence.

Homeric heroes occasionally engage in dialogues with their heart, liver, or stomach. Something that might be interpreted as if their psyche confronts itself with their thumos – urges/passions.

When Jason is later subjected to Medea's reckless wrath, he explains it as her being possessed by an alastor, an inner demon created by unquenchable shame over committed crimes, which have not been reconciled through any appropriate religious rites. However ... the modernity of a writer like Euripides consists in the fact that he makes Medea a struggling human being, someone who is well aware of the fact that she is not possessed by any demons. She knows that is her sense of reason that struggles against her often uncontrollable, passionate nature. Her thumos has been poisoned by ther desire for Jason's love. Medea's misdeeds are not caused by any lack of insight. As when a slave begs for mercy from a cruel master, Medea fights against her violent passions:

I know what evil deeds I intend to commit, but my thumos is stronger than my good intentions. My Thumos is the root of a my worst actions.

Medea's sharp intellect cmight be characterized by the concept of mêtis, knowledge. It is not an abstract, deeply reflective thoughtfulness, which the ancient Greeks denoted by the concept of sophía, wisdom, but rather of a concrete, action-oriented intelligence, which in itself includes wisdom as well as prudence, cunning and acumen. Qualities that Homer bestowed on his hero "resourceful", polú-tropos, Odysseus. He was certainly encumbered with an overabundance of polýmêtis, multifaceted mêtis. As with Medea such qualities could in Odysseus turn into cruelty and seemingly completely unjustified acts of violence. But such deeds nevertheless seemed to be connected with a certain infernal logic.

Odysseus and Medea were practical-minded individuals. Medea did for example have her extensive and in-depth knowledge of all medicines, tools and toxins present in nature and knew quite well how to benefit from them all.

When Jason had professed his love, promised her marriage and a happy life with him, Medea declared that she would become his Ariadne by providing him with the red thread with which he would be able get out of the tangled labyrinth he had ended up in. But woe betide him if he acted like Theseus who had abandoned his Ariadne. If Jason would ever dare to abandon his Medea, she would not let it happen with impunity, like that weak maiden Ariadne! No, no, Medea was made out of other scarp and grain.

She was to give Jason an ointment with which he had to lubricate his entire body. Thus he would become invulnerable for one day and endowed with superhuman courage and undiminished strength. Jason would thus succeed in his otherwise deadly missions; Tame the fire-breathing bulls and defeat the army of demonic warriors.

Furthermore, Medea would make sure to put to sleep the monstrous snake that day and night kept watch over the Golden Fleece and she would then accompany Jason on the return journey. Her magic skills would protect him and his crew from all the dangers that threatened them.

Medea was convinced that she might be able to master all this. But, could she trust Jason? What she wouldn't be able to withstand was if Jason abandoned her in a foreign land, while breaking his promises to be faithful to her forever and protect her and their potential offspring.

After telling him all this, Meda instructed Jason with the utmost care as to how he should proceed during the difficult trials of tomorrow.

Everything turned out as she had predicted. A betrayed and enraged Aïtes was forced to witness how the invulnerable and superhumanly strong Jason subdued his ferocious bulls, harnessing them to the heavy plow, sowing the dragon's teeth, and defeating the demon warriors. As blood flowed between their mutilated, dead bodies, Jason rushed to Argo, which set sail for the nearby island where Medea was waiting in the grove where Aïtes had nailed the Golden Fleece to the sacred oak.

The day of trials was over, and now Medea and Jason stood in front of the Golden Fleece that shone in the darkness of the night, while the huge serpent came slithering upon then.

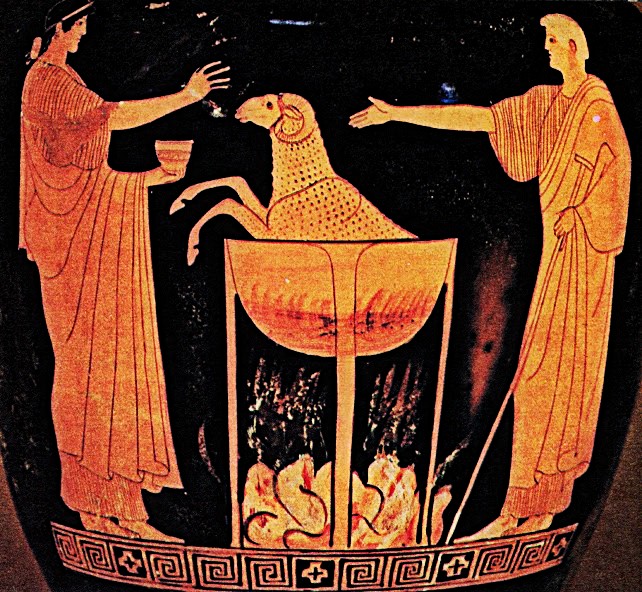

What happened next is unclear. The legends that Apollonius retold, and based his story on, were as mentioned, ancient, multifaceted, and often contradictory. Most of them told, as Apollonius did, that it was Medea who, with one of her drugs, sedated the snake so that Jason could kill it and then steal the skin.

In other legends, Medea put the monster to sleep with hypnotic gestures:

Or Jason drugged and killed the monster on his own, all under Medea's supervision.

A red-figured ancient Greek vase painting on the bottom of a kylix provides an even more dramatic and now unknown version of events, during which the monster appears to be devouring a seemingly lifeless Jason, but here it is the goddess Athena who appears to intervene to save him.

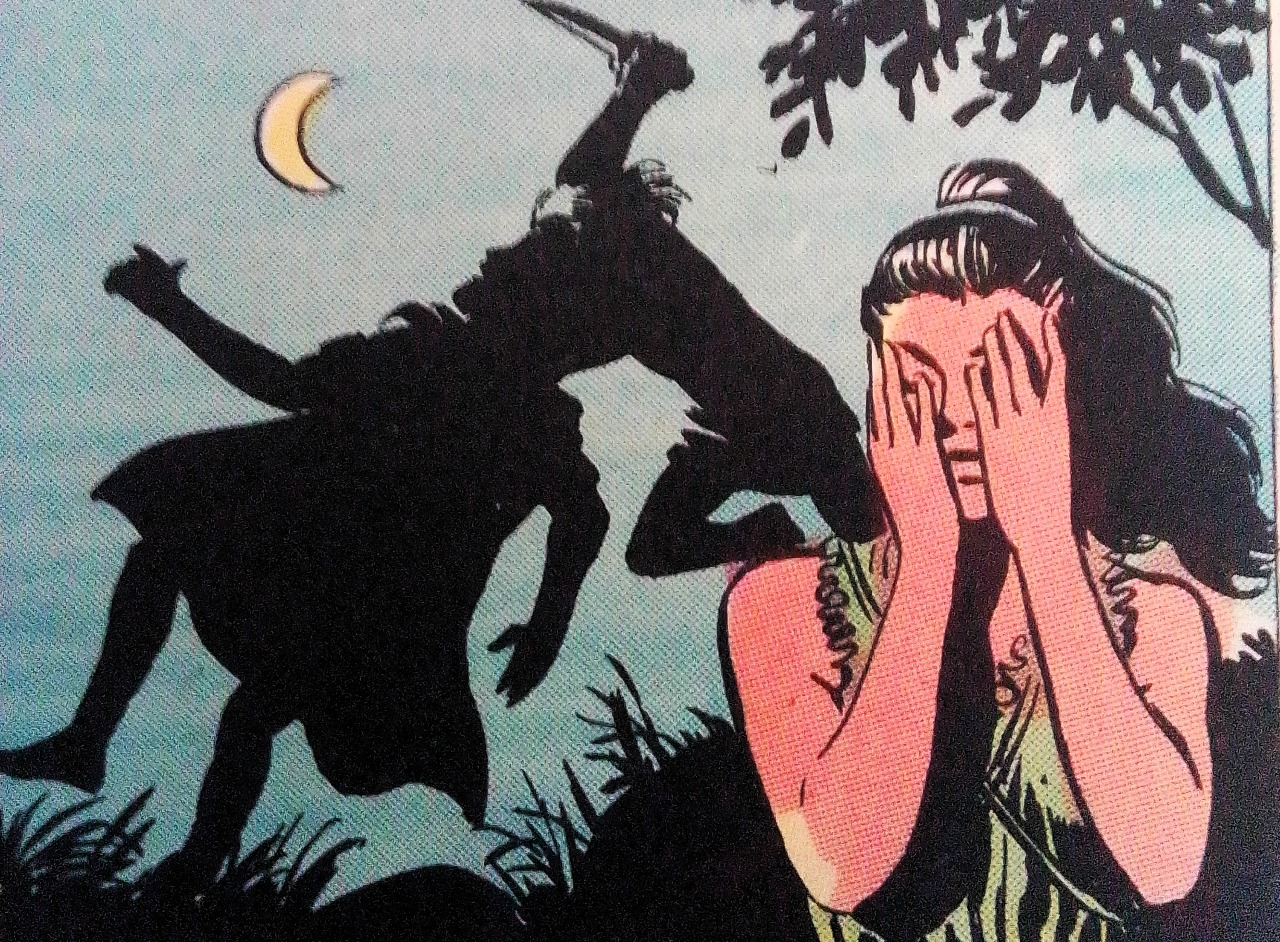

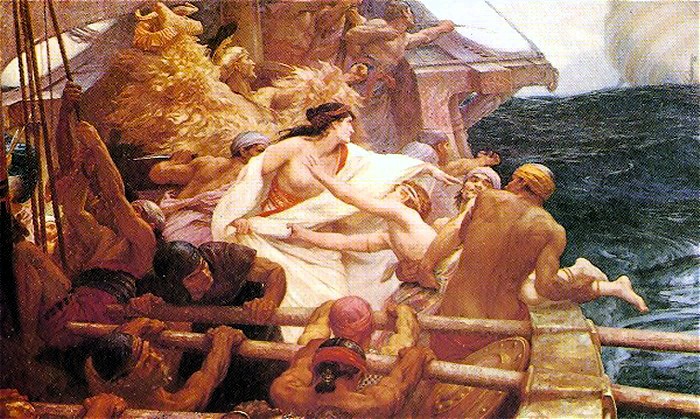

In any case, the newly in love couple managed to bring the Golden Fleece aboard the Argos and then fled across the sea, pursued by Aïte's fleet, led by his son Apsyrtus.

When the Argos reached the mouth of the Danube on the other shore of the Black Sea, they found themselves encircled by the ships of the Colchians, and in order to escape with their lives, the Argonauts were forced to negotiate with the superior force.

Apsyrtus set the conditions – the Greeks could keep the fleece, but King Aïtes demanded that Medea returned to Colchis with her brother. Jason agreed to the arrangement. No wonder the passionate Medea was furious. Less than a few weeks ago, the coward Jason had sworn to gods and future generations that he would be faithful to Medea, to provide her with his protection and love her until death came. Strangely enough, he was now suddenly prepared, not only to save his own skin, but that of the ram as well, and deliver Medea to a vengeful, furious father!

It was the first time Jason faced Medea's rage and he immediately backed down and together they decided to murder Apsyrtos. Under false pretenses, Medea lured her little brother to a meeting during which Jason murdered him.

The betrayal and fratricide left deep marks on Meda's soul, now there was no turning back. She had trodden the path of crime, not only by betraying her father and her country by stealing the Golden Fleece but, even worse, by murdering her brother. And all this for the love of a treacherous wretch who dependent on her strength and intelligence.

Here, too, the legends give different versions. In his masterful play, Euripides followde the same version as Apollonius, while other authors, such as Seneca and Pasolini, used an even crueller version that makes Apsyrtos considerably younger, an innocent child who accompanied his older sister on the journey to Greece.

When Aïtes appeared with his pursuing fleet, Medea mercilessly dismembered her younger brother and threw the body parts in the wake of the ship, in Pasolini's version, behind her chariot, so that the pursuers were forced to stop to pick them up. The ancestor worshipping Greeks were very careful to take care of the corpses of their kinsmen.

Aïtes fleet proved to be much larger, more ruthless and better armed than anyone could have imagined. It blocked Argos' return journey and during ever-perilous adventures, the Argonauts were forced to make their way through the rivers of Europe down to the Tyrrhenian Sea and then sailed down between Scylla and Charybdis until they finally reached the island of the Phaeacians, whose king warmly welcomed them. However, the Colchians' large fleet was anchored in the sea off King Alcinous' island and demanded Medea's extradition.

According to the gods, the Colchians had the right on their side. Since Medea and Jason were not married, Medea was still her father's property. With Hera's blessing, and in the presence of nymphs, Medea and Jason were therefore married, and with the help of the Phaeacians, the Argonauts then managed to make a break through the Colchian blockade.

However, the trials were not over. The Argonautes were forced to drag their ship across the scorching Libyan deserts and on the coast of Crete they were attacked by the enormous bronze giant Talos, but through Meda's intelligence and magic tricks and Orpheus' incantatory music, they finally made it to Iolchis.

Of course, the Argonauts were received as heroes. They had completed their seemingly impossible mission and brought the Golden Fleece back with them, and the Greeks rejoiced to have their youthful, universally admired heroes with them again.

Neverthelss, new problems awaited and it was again Medea who had to deal with them. First... Jason's father, Aeson, was dying, weakened after a miserable life being imprisoned by his brother Pelias, who was still in power, though weak and dying as well. What Jason now insisted on was to heal his father and take revenge on Pelias.

We have now left Apollonius of Rhodes' Argonautica and it is instead Ovid who tells us about Medea's further fate in his voluminous Mertamporphosis, this insightful and lyrically fascinating encyclopedia of mythical love stories.

To make Jason's happiness complete after their celebrated arrival, despite all Jason's shortcomings, the poison from Cupid's love arrow continued to flow through her veins, so Medea undertook to rejuvenate the dying Aeson. Again, her love had caused her to succumb to Jason's flattering eloquence:

I grant, dear wife, that you saved me from death; you have given me all., and the sum of your many kindnesses truly pass belief. Yet I ask, if your magical powers can do it – and what they can they not? – Substract a few of my many years to add to the years of my father.

Jason's filial affection moved Medea to tears, and she assured Jason that with great effort she could certainly rejuvenate Aeson without causing her handsome husband to age.

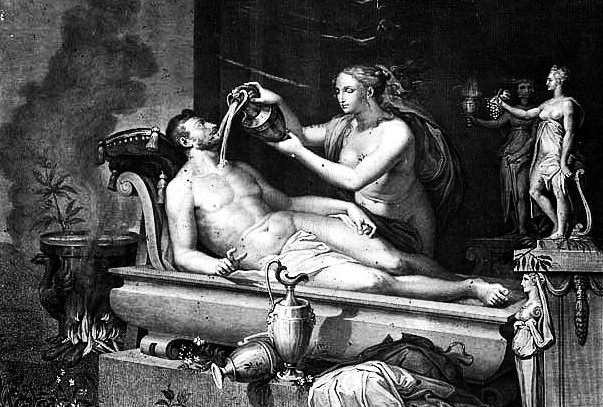

In a loose-hanging robe without knots, she went during the night to the temple of Hecate to ask the Goddess of Darkness for her assistance. Then Medea took off her garment to purify herself in the water of sacred river: She immersed herself under the moonlight then she dressed flew away in her dragon-drawn chariot over the world to collect all the hard-to-find and exotic herbs required for her magical brew. Like Seneca after him, Ovid gave an account of all the ingredients for rejuvenating ointments and drugs required for Medea's magic. A description that reminds of Shakespeare's lyrical descriptions when he in his Macbeth described the witches' drug preparation.

When everything was carefully prepared, Medea put Aeson into a deep sleep, emptied his body of blood, and replaced it with the witches brew she had carefully concocted. And lo and behold, Aeson was resurrected as a youngster, strong and beautiful as his own son. Strangely enough, the legends do not tell us what happened to Aeson after he had been rejuvenated.

However, Jason was not satisfied with this miracle. He now wanted Medea to use her magical skills to exact the revenge he had so long brooded over against the hateful Pelias. This episode in Jason and Medea's fateful relationship is also mentioned in a drama by Euripides – Alkestis.

After returning from Colchis, Jason and Medea lived as respected citizens in Iolchis. Pelias was still king, but completely powerless. His daughters, Alcestis and her three sisters, who, like others in Iolchis, had been amazed by the miracle Medea had accomplished with Jason's father, and did now approach Medea urging her to rejuvenate their father as well.

The cunning Medea demonstrated her art by butchering an old ram, cutting it up and boiling it. Strangely enough, the ram was transformed during the process and soon a beautiful little lamb jumped out of the pot.

Medea convinced Alkestis and her sisters that they could proceed in a similar way with their elderly father. They murdered and dismembered the reluctant old man while Medea boiled plain water and sang her magic spells over it. After the sisters put the pieces of Pelias into the pot they became so over-boiled that they could not even be taken to the grave, which for the Greeks was the most horrible thing that could happen to a revered deceased. The people of Iolchis were furious at Medea's actions and she and Jason were forced to flee to Corinth, which at the time was ruled by King Creon.

Creon welcomed the famous refugees with open arms. But in Sophocles' play Antigone, we have learned that Creon was in fact a tyrant who considered himself to stand for family honor and upholdin the will of the gods, but actually acted in the opposite way.

In Antigone, Creon aggressively preaches family honour, tradition, and submission to the will of the gods. However, when one of his sons was killed during a rebellion against him, Creon, against all rules and traditions, forbade everyone to bury his deceased son. Howver, Antigone, could not accept such disrespect for the dead and buried her brother. Creon sentenced her to be buried alive, but when he changed his mind at the last moment, it was already too late – Antigone had killed herself, and so had her brother Haemon. Creon behaved just as buffoonishly towards Medea.

Women did not have many rights in ancient Greece. They were the property first of their fathers and then of their husbands. Euripides Medea exclaims in despair:

Of all creatures that have life and reason, we women are the most miserable of specimens!

When a man was not happy in his marriage, he always had the opportunity to leave home and find an outlet for his frustrations in the company of other men and women. However, if a woman behaved in a similar way, she was considered to be a shameless creature, and a divorced woman was despised as if she had not been good enough for her husband. It was said that the women were safe in their homes, but where was their freedom? They were entirely at the mercy of their husbands' arbitrariness. Men boasted of their courage and combativeness, but as Medea stated – she would rather face an enemy on the battlefield than go through all the dangers and severe torments that childbirth entailed.

And what about her? What kind of security and respect did Medea have now? Abandoned and homeless, she had previously been a disrespectful man's plaything. A possession that now that he had new interests could simply be thrown away, along with their children. A cruel man who treated her as if she were a mere spoil of war and who, when he found another love, no longer cared about his children, because he could within his new family get new ones with pure Greek blood in his veins.

Medea had no father, no brother, or other relatives who could help her face the torment and contempt that now befell her in a foreign land, where she lived alone, feared, and displaced. Jason had turned his back on her, from the shadows she had seen him marry a younger woman – the man who had sworn by the gods to be forever faithful to her. Whose life she had repeatedly saved and defended at the risk of her own life, to whom she had given her all. She – the daughter of a king far more powerful than the pathetic little despot Creon. She, the granddaughter of the sun itself, had now been forced to witness how Jason had married the beautiful Creusa, a descendant of Sisyphus, a villain who had been condemned to be tormented in Hades.

It was said that Greek women were withdrawn and peaceful, but not Medea. It was love that had forced her to give up everything for Jason, and it was his self-love that tore him away from her. If love was wounded in a woman like Medea, her thumos, body-soul was wounded as well, igniting the holy wrath that once filled Achilles:

Sing, Goddess, sing of the rage of Achilles, son of Peleus— that murderous anger which condemned Achaeans to countless agonies and threw many warrior souls deep into Hades, leaving their dead bodies carrion food for dogs and birds— all in fulfilment of the will of Zeus.

The anger that burned in Achilles and Medea was mênis, an uncontrollable anger that took the form of an almost cosmic rage and was thought to have been provoked by crimes committed against social norms. By Seneca, Medea raged:

Light is the sorrow that allows itself to be hidden and reconciled. Atrocities cannot be covered up, they demand action. With ancient powers I will seek my vengeance, from the depth of my bowels it will be summoned. All my feminine fears will be dispelled the rage that has been hidden under the snow of Caucasus. I remember the kind deeds of a young girl, but now a heavier anxiety wells up. The wrath born out of a wife wounded by evil deeds. Crime must with crime be atoned.

What triggered Medea's mênis was perhaps not only Jason's betrayal. In Seneca, even more than with Euripides, who was his model, it was also Creon's ruthless behaviour – he appears to be an ancient xenophobic Trump – that added salt to Medea's wounds when he ordered her to leave Corinth immediately. When Jason married his daughter, Creon wanted to get rid of Medea at all costs.

In Seneca's house, the despot ruthlessly attacked the woman who was a stranger to him;

Begone! Cleanse our Kingdom from your filth. Take your deadly herbs with you, free us from our fears. Go to your far-off lands where you can invoke your hateful gods!

And she didn't find any support from Jason. He was at home and knew how to deal with the situation. He no longer needed Medea's magic tricks – his journey and difficult mission had succeeded thanks to her self-sacrificing efforts. But that was them. Thanks to Medea, his old father was now transformed into a young man of good health. His archenemy Pelias was dead and gone. Creon liked him and gave Jason a safe home in his rich and powerful city. He had fallen in love with and married the tyrant's young, beautiful and submissive daughter. Something that had given him Corinthian citizenship and upon Creon's death he would become king of the city. However, none of this benefited his passionate and foreign ex-wife (whom Jason deep down was afraid of).

It is worth noting that when Euripides' drama 431 f.Kr. was performed in front of a huge audience of mainly male Athenians, their greatest statesman, Pericles, had a few years earlier introduced a "citizenship law" which meant that in order to be a voting Athenian, both parents of a man (slaves and women were not allowed to vote) had to be Athenians.

A marriage could only be dissolved by the husband announcing his divorce in front of witnesses and the wife being returned to her father, or a relative on her father’s side, together with the dowry. This also meant that if they wanted to retain their citizenship, all Athenian men married to foreign-born women had to divorce them, and the children born within such marriages lost their citizenship.

This is despite the fact that Pericles, after divorcing his wife, lived in an open relationship with Aspasia, who was born in Miletus and was consequently considered to be a metic, foreigner, and according to his own law, Pericles could not marry her.

Is the situation recognizable? An exalted political leader passes a law that restricts the rights of immigrants, but nevertheless considers himself to be above the law and living with an immigrant, who was furthermore considered to have been a fortune-seeking courtesan.

Medea defended herself against the accusations of the despotic Creon – had she not through her courage and knowledge saved the lives of Greece's foremost youthful fighters, among them many Corinthians,? Was she not the daughter of a king far more powerful than Creon, a father who was also the son of the sun itself? Had she not, after having abandoned everything she had and been forced to flee for hers, her husband's and her children's lives? Had she not chosen to live in a city whose citizens she had helped and protected through her experience and knowledge of healing crafts? Creon was relentless, Medea had to leave Corinth immediately.

Did Jason stand up for wife and kids? Hardly. Instead, the newlywed narcissist defended his behaviour by portraying himself as a victim who had done everything for his family. It was not Medea who had assisted him and the Argonauts, rejuvenated his father and taken revenge on Pelias. It was her passion, her love for him, for Jason, that had driven her to do what she had done. thus it was the gods who had created her infatuation and not Medea whom he should thank. Now it was all over, both the love and her power. All that remained was her rude barbarism, which had made her behave disrespectful towards Creon and his daughter Creusa, who only wished Jason and Medea well. Through her refusal to show appreciation, Medea had become a nuisance of herself and became an embarrassment to him. Creon and Kreusa wanted to make him and the children part of their family. A glorious future awaited them and after Creaon's death, Jason would become king. Why was Medea so reluctant to a better life, when she could remain in the household as his concubine? If Creon had said that the children would also be expelled, he surely done so in anger at Medea's intransigence. For the good of all, Medea had to leave, with her magic skills she would surely be able to manage on her own. Nevertheless, Jason would try to persuade Creon to let the children stay and Creusa would then become like a mother to them. Jason, with his charm and experience, knew how best to deal with women.

Later writers have often stressed Medea's alienation. Pasolini made his film Medea in 1969 at a time when the exoticism and alternative views of "primitive" cultures were popularized. Inspired by anthropologists/philosophers such as Frazer, Lévy-Bruhl, Jung, Lévi-Strauss, and Girard (who ten years later also influenced the ending of Coppola's Apocalypse Now), Pasolini portrayed Medea’s Colchis as a primitive society with fertility rites and human sacrifices, which, despite its cruelty, was closer to nature and human passions than Jason's Greece. Medea's revenge, the murders of her sons, Creon and Creusa, were thus by Pasolini placed within a ritual context and thus became both a revenge and a purification process.

The Italian Corrado Alvaro considered his Medea in his 1950 drama Medea's Long Night in relation to the recent Second World War, with its racial hatred and extermination camps.

In Alvaro's case, Creon and the Corinthian’s feared Medea to such an extent that, in derad of being poisoned, they did not dare to touch anything she had handled. Jason was accepted, he was a Greek like them, but they turned Medea and her children into subversive demons, capable of defiling the Korinthic culture. The presence of the strangers meant that they were considered as being infected by the plague. In Alvaro's drama, it was not Medea who killed her children, but a Corinthian lynch mob that slaughtered both her and the children.

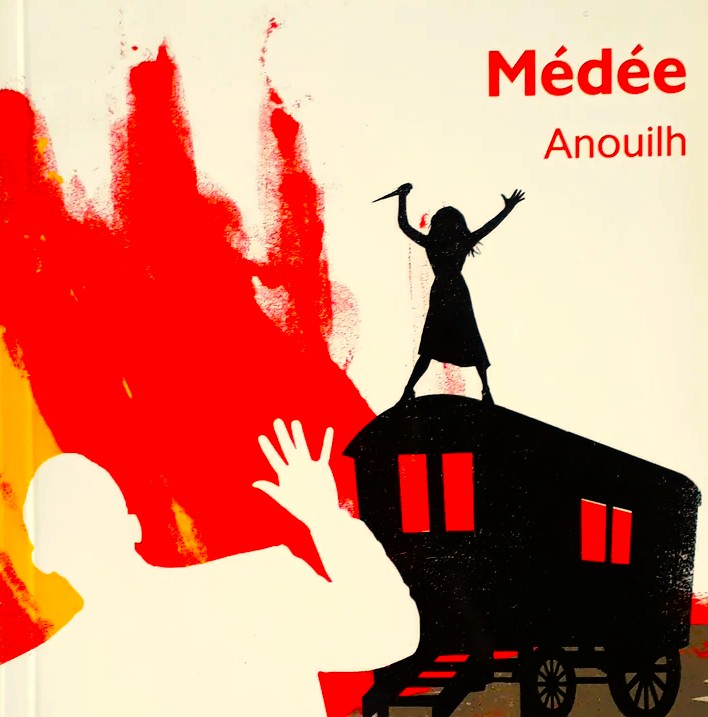

In his Médée from 1946, Jean Anouhil made Medea wander around the countryside like a gypsy with a caravan, until Jason decided to leave her to seek safety and oblivion with Creusa and Creon.

Anouhil's Medea was a sensual creature connected with Nature, civilization did not attract her at all. Her love for Jason was dominant, erotic, and palpable, while Jason was an idealist, albeit an ambiguously cynical one. He wanted to live an easy-to-understand, "moral" life with fixed rules and an uncomplicated everyday life. The free roaming life he placed had enjoyed with Medea did not attract him abynore. The aging, but still passionate, Medea frightened him with her unbridled wildness.

I want the world, not the chaos where you led me by the hand. I want it to take shape at last. You are probably right in saying there is no reason, no light, no resting place.

But it was precisely meaning, light and rest that Jason wanted. Medea could continue with her unfettered existence, but without him and the children. When Medea kills Creusa and her children at the end, she screams in mad rage from the roof of her burning carriage:

Now I have found me scepter again. My brother, my father and the fleece of the golden ram are given back to Cochis. I have found my virginity which you tore from me. I am Medea at last and forever! I am your little brother and you wife! I, the horrible Medea!

Jason left Medea to be consumed by the flames and refused to let people put out the fire.

The Austrian Franz Grillparzer's The Golden Fleece, which was completed in 1820, was a trilogy of plays – The Guest, The Argonauts and Medea. It was a story of development in which we get to follow Medea as a young woman; an Amazon riding and hunting in the mountainous areas of the Caucasus. In the second part, Medea matured and immersed herself in the dark arts of magic, while falling in love with Jason and leaving her country, until in the final part she tried to adapt to her new life in Thebes.

According to Grillparzer, the different plays corresponded to phases in Medea's life. The first one ended with Medea's despair through the realization that her father had cowardly and deceitfully used her to murder Phrixus, who came to Colchis with the Golden Fleece. For Medea, it meant the end of her naivety, through which she had believed that her father was an irreproachable hero. Medea's belief in her innocence was lost in the second part of the trilogy, when she was driven to theft, betrayal and murder through her love for Jason. In the third part, she finally came face to face with death and despair.

Just now I took a break in my writing to do some TV watching. Lately, I've been trying to follow an extremely complicated German TV series, Dark, which intricacies are linked to time travel, black holes and the Higgs boson, among other things. In episode 23, called Life and Death, one of the characters said:

A human lives three lives. The first ends with the loss of naiveté, the second with the loss of innocence, and the third with the loss of life itself.

A strange coincidence. Could this have something to do with Grillparzer’s Medea? My searches online yielded no results.

In the last Grillparzer play, we meet a subdued Medea, although passion glows beneath the surface. Creusa is not an insecure young lady, but has the same age as Medea, a childhood friend of Jason's who only thinks well of him. Medea, who wants to adapt to the enlightened "decent" Greek life, has buried her magic paraphernalia and is dressed like a Greek woman. She seems to look up to Creusa as a role model able to teach her to conform to the expectations of the Greek-born Jason, to become what she thinks he wants her to be – a "civilized and decent" woman.

In a key scene, Kreusa tried to teach Medea to play the lyre. But, Medea complained. During her youth, her hands had become rough after handling horse reins, spears and bows. They were not as refined as Kreusa's. "Rebellious fingers!" she exclaimed, “I want to punish you!”

But Medea learned to play and sing a song that Creusa knew that Jason loved when he was young. Medea succeeded in singing it and then asked Creusa if she realized the true meaning of the wors – they were about a beautiful, young hero who with a sure hand crushed his enemies and made women fall for him. No, Creusa hadn't thought about the words, only sung the song. Medea was surprised – are Greeks only interested in sounds? Didn't they think about the meaning of what they sang and said? Like the lines:

To beat all enemies and steal the heart

from all the beautiful virgins!

That's exactly how Jason was – egocentric. He didn't care about other people's feelings. Thoughtless as a child, he hurt the people around him and believed himself to be innocent of the suffering he caused others, not least through the faithlessness he showed women.

Creusa became violently upset. How could Medea utter such things about her husband? This handsome, good person whom Creusa had known since childhood. Medea replied, "Because I know him better than you. I have been by his side when he has been tested. I have seen and experienced his weaknesses." Creusa rushed out of the room.

When Medea later played for Jason, the lyre broke in her clumsy hands, she couldn't possibly move herself in the sophisticated salons of the Greeks. And even worse, her own children were ashamed of her and preferred to resort to the gentle Creusa, who caressed them and babbled:

Come here to me, poor, homeless, little orphans! So young, and yet misfortune bows you down So soon! So young, and oh! so innocent!-- And look, how this one has his father's mien

Medea could not restrain her anger:

They are not orphans, do not need thy tears of pity! For Prince Jason is their father; and while Medea lives, they have no need to seek a mother! were it a spear-haft, or the weapons fierce of the bloody hunt, these hands were quick enough!

When Jason has displaced Medea and married Creusa and the newlyweds will keep the children while Medea is driven into exile, her skull shattered and oblivious to all cultivated behavior, her wild animal instincts took over Medea. She killed her children so they would not be overshadowed by those who would be born through Creusa's marriage to a cold and disinterested Jason.

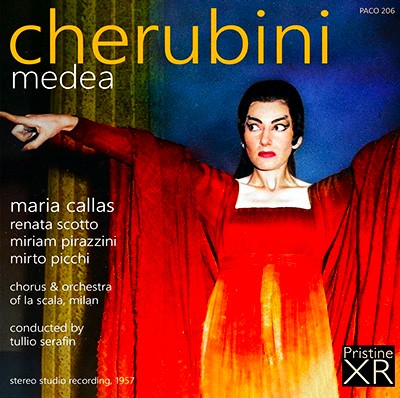

Medea's unsuccessful lyre playing indicated how great the role of music was in ancient Greek society. There are many indications that the Greek dramas were sung, to a much greater extent than we can now imagine. Perhaps opera might be considered to be an heir to this kind of drama. In any case, Medea's passionate drama has inspired several operas. Perhaps most famous of all Meda performances was Maria Callas' portrayal of the here in Luigi Cherubini's Medea, which premiered in Paris in 1797.

Cherubini's opera, which had been popular in its time, did however come to be lying fallow more or less until 1953 when Callas made an explosive performance in the role of Medea at La Scala. Since then, the opera has been a common feature in the global opera repertoire.

With Medea, Leonard Bernstein made his debut at La Scala. He had been called in at the last minute as a replacement, but did nevertheless give an energetic and personal touch to the performance, which exemplarily highlighted Calla's grandiose romantic interpretation of the displaced and furious woman, She gave Medea a voice that dripped with hatred and revenge. It became one of the greatest roles of her life and she sang it several times. Callas was magnificent, as if being possessed she dominated the performances. Her voice could do almost anything, and what she couldn't do with it, she forced it to approach.

The biggest shortcoming was Calla's inability to keep her voice free and unobstructed as it rose in pitch, something she compensated for by putting more effort into it. Callas had the bad habit of carrying her chest voice too high, which for her meant a great effort, not least because it was combined with her constant struggle against her weight. This, and the demanding roles, certainly accelerated the ultimate destruction of her unique voice.

In Hamburg in 1959, Callas' voice cracked in the opening scene of Verdi's Macbeth and then it went downhill. Her acting continued to be beautiful and cinematically precise, but the conductors increasingly tried to make the orchestration dull her progressively deficient vocal resources – a damaged voice can never be repaired. Callas' last tour took place in 1974, but by then her voice was almost gone. Three years later, she died of a heart attack, at the age of 53. There is no film recording of her Medea performances, except for a few scenes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m7Lyjm9P7BE

In Cherubini’s opera, Medea is killed in the fire she had started in Creon's palace, but in most other versions, such as those by Euripides and Seneca, she first talked to the self-righteous Jason, who claimed to be able to take care of their children and persuade Creusa to become like a mother to the boys, though both he and Medea knew that Creusa hated them.

Medea pretended to be compliant and suggested to Jason that she, as a token of reconciliation, could give Creusa her finest cloak and a tiara, These had been given to Medea by her grandfather, the Sun (in some versions, the cloak is the same as Jason's gift from the Hypsipyle, so treacherously abandoned by him). Jason agreed with some hesitation: "Why give away something so valuable. But... all women are certainly fond of precious things." And indeed, when Medea had sent her sons with the gifts to Creusa, she at first turned away from the boys in disgust, but when she laid her5 eyes on the magnificent robe and sparkling tiara, she became delighted and immediately put them on.

However, Medea has poisoned the gifts. They clung tight to Creusa and burned with such intensity that they caught fire, her father Creon threw himself on his screaming daughter, but the fire spread to him as well and soon the whole palace had caught fire.

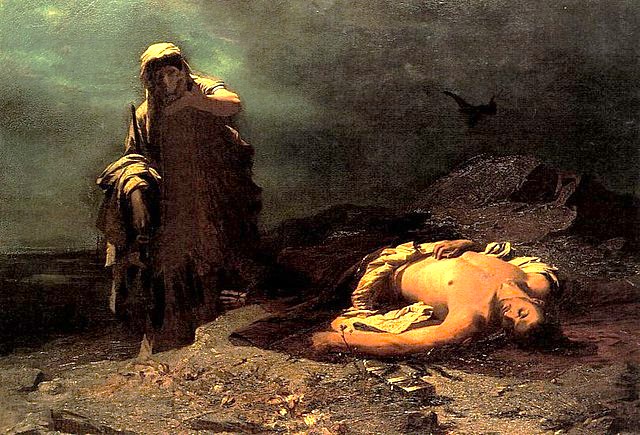

Meanwhile, Medea had slit the throats of her children and when Jason appeared, she was standing on the roof of the burning palace with the dead boys in her arms. In Euripides, Medea left the stage in her dragon chariot, but in the much more lugubrious Seneca, she had before that hurled the children's corpses down to Jason, accompanied by a prayer to the gods:

Let him walk in terror through unknown lands, exiled, hated, desolate without a home; too notorious and despised to become a guest anywhere, let him knock in vain at strange gates and long for me, his wife! And, one last revenge … let him beget sons who resemble their father and daughters like their mother!

Seneca's plays are far more gruesome than their Greek counterparts, and although they have constituted an important inspiration for masters such as Shakespeare, Racine and Corneille, they have also by many been dismissed not only as unperformable, but also as "absolutely illegible". A verdict I actually can't agree with, Seneca's dramas are actually in my opinion quite OK, with their striking rhetoric and macabre shadow play.

Seneca’s Medea is characterized by a heavy rhythm and in it he makes an interesting connection between the singer Orpheus, who was one of the Argonauts and whose singing could sooth and subdue even the treacherously alluring tones of the sirens and calm the stormy sea, while Medea with her magic tricks was able to achieve similar miracles.

For a Stoic like Seneca, Orpheus and Meda were dangerous extremes. Through their art, they mastered the forces of nature, something that we humans should instead submit to. Nature, despite its unimaginable grandeur and cruelty, is the basis of all human life. If we humans like Orpheus and Medea manipulate it, it can easily lead to chaos and disaster.

During the Middle Ages, Medea became popular within Europes, sophisticated court circles. In the popular Pretiosa Margarita Novella, The New Pearl of High Value, she appeared as a guide for alchemists. In Ovide Moralise, she fought the Antichrist as an ally of God. In Geoffrey Chaucer's The Legend of Good Women, she became the epitome of a betrayed, wronged wife, while she became a nightmare character in Raoul Lefèvre's L'histoire de Jason.

It was as a female idol that Medea made her entry into the "courtly" culture, and it was not in the version of Euripides or Seneca, but in the form of Ovid's milder and more elegant poetry. Medea's greatest impact was probably through the anonymous Ovide Moralisé (c. 1316-28), an enormous, wide-ranging poem that changed the way Ovid's originals were read and how Medea and other classical heroes and heroines in the later Middle Ages came to be part of court culture. But even before that, Medea had been integrated into the European storytelling tradition, mainly through Benoît de Sainte-Maure's epic Roman de Troie from around 1160. There, Medea (before the child murders) appears as attractive, wise, noble and virtuous.

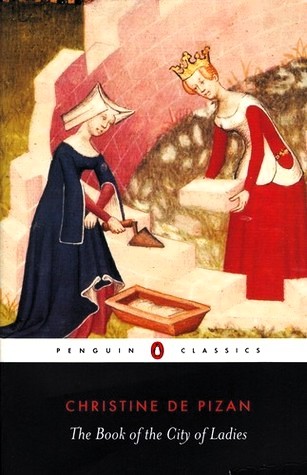

Medea, even more than her horrible side that sometimes breaks out, seems to retain her status as a female role model all throughout the Middle Ages. Christine de Pizan did for example, in her Le Livre de la Cité des Dames, The Book of the Women's City, from 1405, emphasize Jason's disloyalty to Medea and made no mention at all of her murder of her children.

According to Christine de Pizan, Medea was an extremely beautiful, tall and slender lady with a profound knowledge of the forces of nature. In learning she surpassed all other women, for she knew the properties of each plant and what spells they could be used for. With a song that she alone knew, Medea could darken the skies, draw the wind out of gloomy caves in the depths of the earth, awaken storms, make rivers stop flowing, brew all sorts of poisons, create fire out of nothing, and burn down whatever she wished, as well as performing all sorts of other miracles.

So why did Medea become so popular among troubadours and women writers? Within noble families, women were used as a kind of commodity to strengthen coalitions and create peace between warring factions through marital alliances. However, within a society that valued warfare, it could also be a risk to marry off women as a token to ensure peace. Several married women could end up in unhappy and awkward situations, in particular if their husbands did not have any political/economic interest in them.

Medea's story resonated in such a society. How she of her own volition gave herself to Jason and thus betrayed her male relatives, both father and brother, and how she then, despite her intelligence and great knowledge, became hopelessly dependent on her husband's contacts, position and power. What could a betrayed and abandoned woman do in such a subordinate and vulnerable situation? Several educated, medieval women considered themselves to be their husbands' slave girls.

A writer who much later brought out the feminist perspectives from Medea's history was the East German writer Christa Wolf, who in her novel Medea: Voices from 1996 made Medea a representative of free thought. In Wolf's work, Medea is a pragmatically minded woman who follows Jason on his journey from Colchis, not so much for the sake of her love but more out of disgust for her father's despotic rule. In Wolf's case, it is not Medea and Jason who have killed Medea's brother Apsirto, but the corrupt Aïtes, simply because he considered him to be a threat to his authoritative power.

Medea followed Jason to Greece because she imagined that country to be a haven of rationality and humanism, but she was cruelly disappointed when Jason abandoned her and she realized that Creon was just as murderous despot, just like her own father. Creon had had his eldest daughter Ifione murdered and used his younger, Glauce (Kreusa), as if she were a commodity to bind Jason more tightly to him.

Medea tried to help and instruct Glauce, but the poor girl killed herself. Medea, according to Wolf, was also not guilty of the death of her children – falsely accused of a ritual murder, she was sentenced to be banned from Corinth, while her sons were allowed to remain with their father. Later, in Medea's absence, a xenophobic lynch mob stoned her children to death and a false rumour was spread that it was she that had poisoned them.

With Euripides, Seneca and Ovid, Medea traveled in her dragon chariot from the scene of the murder. Ovid tells how she sought refuge with King Aegeus in Athens. Medea had previously met him in Euripides' drama and promised that if she had been forced to leave Corinth, she would marry Aegeus and through her sorcery give him the children he desired.

Medea gave birth to hers and Aegeus' son Medus, but when Theseus from one of Aegeus' previous relationships, and who had now grown up without his father's knowledge, unexpectedly appeared, Medea tried to poison him. She considered the appearance of Theseus to be a threat to her own son. However, Medea's intention was discovered at the last moment and she was forced to flee again. Medus later became king of Colchis, Medea's fatherland.

Strangely enough, Medea was rewarded after death by being betrothed to the hero Achilles and with him live in the paradisaic Elysian fields.

Jason's ending was tragic. His hopes for Corinth's royal crown were dashed. The Italian poet Cesare Pavese told in a short story from 1947 how an aged Jason in a temple on Acrocorinto, the Acropolis of Corinth, met Mélita, a temple prostitute who felt sorry for the now old and frail Jason and took care of him.

Jason told Mélita about the adventures of the Argonauts, which had taken place before Mélita was born. Jason could hardly believe that he had been part of all that, which happened as he said "when the world was still young". He had done evil deeds without really understanding that they were actually evil, since he had thought he was strong and "wanted to be like a god."

And Medea? Well, every man meets a seductress at some point. What can a man do about that? Women are mysterious, dangerous and incomprehensible. Who can understand them? It had been a long time since Medea ruined Jason’s life. How and why? Who can understand that? The only thing that seemed to annoy Jason was that Heracles became a god and not him.

Pavese does not tell it, but legend has it that old Jason stumbled down to the sea shore where the wreck of the Argo rested. He fell asleep in its shadow, a heavy beam detached from the hull fell on Jason and crushed his skull.

There are many more stories about the child murderer Medea. She constantly changes shape, is reinterpreted and reappears. She has never existed, but she is nevertheless real, just like Hamlet, Don Quixote and Sherlock Holmes, immortal figures who for many of us have become part of our reality.