SAINT DAMASUS: The First Pope, a Saint, and a Mass Murderer

Rome

What hast thou done with all the famous Roman dead?

For as one enters Rome they seem the dead to see

Walking like ghosts who haunt a house by day,

But in some curious sort of necromancy,

Or magic presence of the place, are put away

Into a world we cannot understand:

For Rome is of the earth, earthy,

And on the stage of Rome, the dead are grand.

By the beginning of the last century Oscar Wilde wandered through Rome, he himself was like a ghost, a shadow of his former witty self who had astonished Europe and the United States with his scandalous personality, quick-witted dramas and sharp aphorisms. Gone was the carefree dandy, left behind was a fat exile, beaten, despised, alcoholic and increasingly lonely man. A ghost walking among ghosts. Wilde was only 46 years old, but was dying anyway, no less than six times had he received the blessing of Pope Leo XIII (note that the current Pope Leo XIV took his name from a potentate who apparently was at all not bothered by Wilde's well-known homosexuality).

When I aimlessly walk around in Rome, it happens that I think of Wilde's poem, especially as I am constantly confronted with something unforeseen confrontations concern ghosts from a bygone era. Meetings that make me delve into Rome's past.

As an example, a few days ago I took a walk in our neighbourhood, which unfortunately lacks the ancient churches that you otherwise find everywhere else in Rome and which I often visit with great interest. Around here, church buildings are from the last century and are generally ugly, lacking atmosphere, but that does not hinder me from visiting them and every time I learn something new there as well. I recently found myself in front of Chiesa di San Damaso, built in 1969 and not particularly beautiful.

San Damaso, or Damasus according to his Latin name? Who could that have been? Obe of Oscar Wikde’s Roman ghosts? I had never heard of him. When I came home, I searched for him in my books. The documentation was not particularly extensive, but if San Damasus had been so important, after all that huge modern church had been built in his honour, then surely, he must have be an important saint?

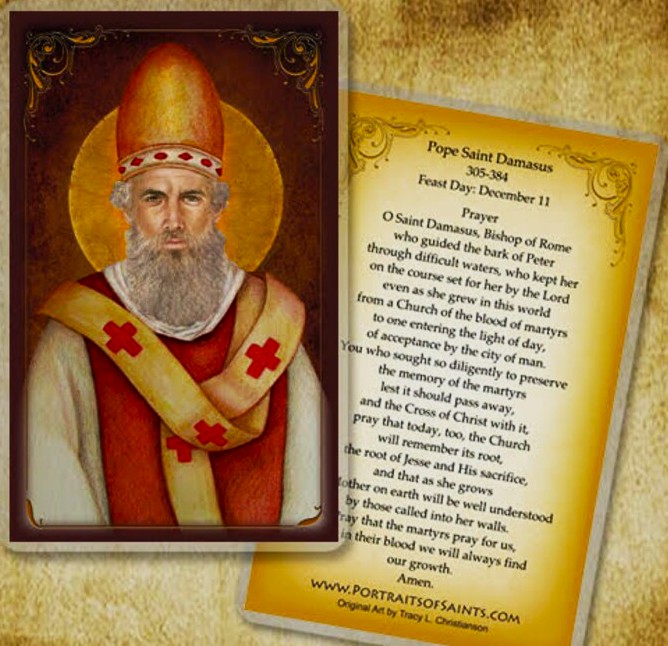

In the Chiesa di San Damaso, I had found one of the small prayer cards that usually are found in Roman churches, on the front they are provided with a picture of the saint and on the back a prayer is addressed to it. On the front of the card I had found it was under San Damaso’s picture written that the eleventh of December had been dedicated to him and on the back there was the following prayer to the canonized pope:

O mighty God, strength and crown of all Thy saints, grant that that we may follow the example of Pope St. Damasus, that lovable keeper of the memory of the Martyrs, that we may praise and imitate them as being a venerable witnesses to our faith. Grant us, O God, to follow the example of Pope St. Damasus, him whom we love and who revealed to us Thy word through the Bible, that we may diligently and faithfully meditate on how we may attain our salvation. Through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Online I found several similar prayer cards:

Bible and martyrs? Somewhere I found that Saint Damasus is the patron saint of archaeologists. Could that have something to do with “preserving the memories of the martyrs”? And what did is mean that he was “revealing Your word through the Bible”? However, the saintly pope did not seem to be as popular as other saints you find all over Rome – Saint Francis, Saint Anthony, Saint John Paul II, Saint Mother Teresa and not least Padre Pio.

So, who was this Saint Damasus? A saint from the time when Christianity was about to become the compulsory state religion throughout the Roman Empire. He was undeniably one of those Roman ghosts that Wilde wrote about in his poem. These lugubrious apparitions which do not hesitate to reveal themselves even during daytime and who emerge from the Roman soil. When I did some research on Saint Damasus, he turned out to exhibit the Roman distinctiveness that Wilde described in his poem. A rather gloomy ghost from a bygone era, an explorer of catacombs, and resurrector of the city's dead, but also an important reformer and propagandist whose decisive actions continue to have repercussions on the Catholic Church of today.

When I visited the church, I looked around in Chiesa di San Damaso to find some traces of this to me previously unknown saint and found a plaque made of porphyry marble. It seemed as if visitors to the church should be informed about who its patron saint was.

The marble plaque told us that Saint Damasus was born between 305 and 306 during a time when "the Church was fighting a fierce battle to find its own identity". It was a burning issue question to be able to establish what was the right faith and at the same time provide a firm foundation for the political and social change that laid ahead of those tumultuous times. Constantine the Great had proclaimed Christianity to fully acceptable and had according to the plaque allowed “Christians to appear in the light of the sun again,” but it was not until Emperor Theodosius I, the last emperor to rule the entire Roman Empire, that the Catholic faith became state religion through his edict of 380, which also made all other faiths illegal, though Judaism continued to be accepted to some extent. The word “catholic” came to be used for the Christian faith approved by the emperor. The word was derived from the Greek, “universal”, “general,” and was used to designate the “Nicaean Creed”.

Saint Damasus originated in Lusitania (the Roman province that later became Portugal and also included parts of present-day Spain), but he was apparently born in Rome. His father was a deacon, i.e. a bishop's assistant with special responsibilities for practical tasks, finances and social activities, and he was also a presbyter, a priest, in the Basilica of St. Lawrence, outside of the walls of Rome and located among the Christian catacombs. Initially, Damasus was also a presbyter in the same church as his father. There are several preserved so-called gold-glass portraits from Damasus' time even if they are called Damasii and some of them are said to depict him, none of them can with any certainty be linked to him.

The marble tablet continued to tell us that St. Damasus "chose to sit on the throne of Peter with the intention of limiting the spread of unbelief". I sensed an exciting story that somehow seemed to be hidden behind the Church's official version of events. There was a hint of violence and censorship under the surface.

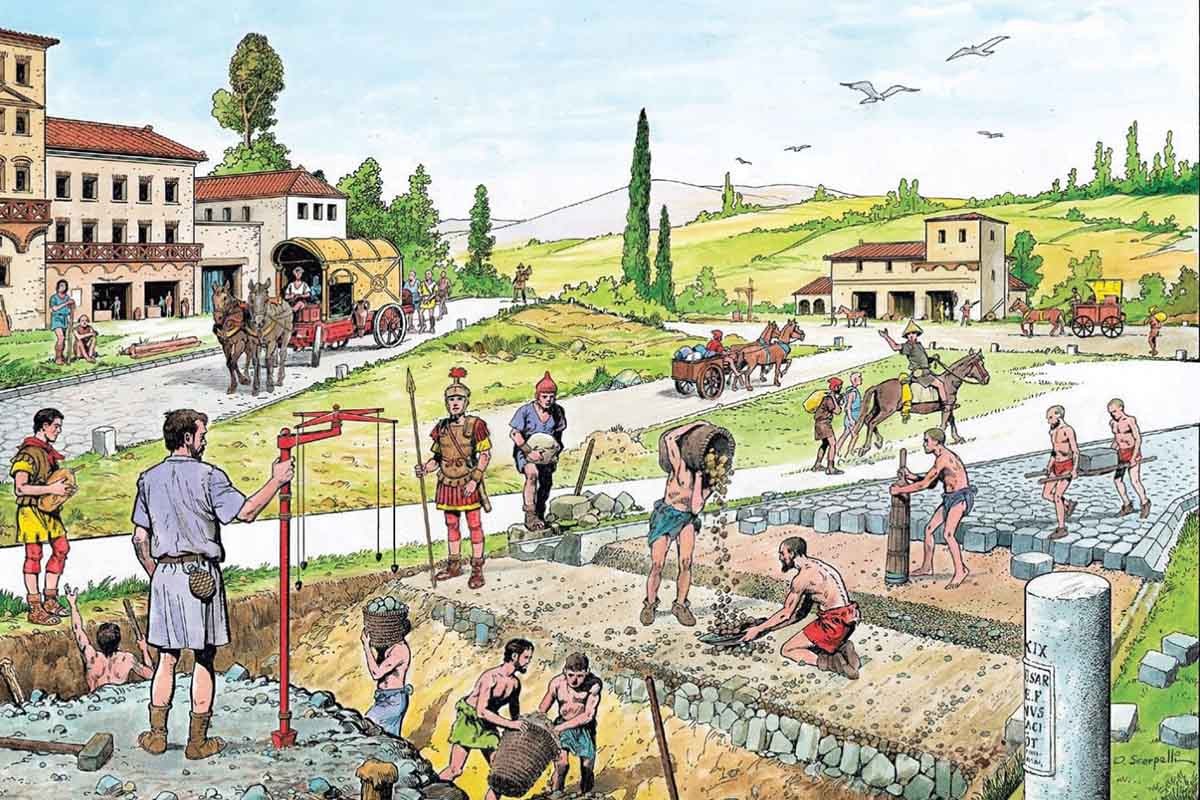

How was the time and world in which Saint Damasus lived and acted? Certainly, the edict of Constantine the Great had in various ways benefited the Christians. He granted and financed the construction of the first St. Peter's Basilica and in 321 Sunday became a day off, while crucifixion was banned as a punishment, the clergy were exempt from taxes and were given the right to use the extensive Roman transport and postal system. These and similar measures contributed to the fact that the forces that wanted to return to the old order after Constantine's death found it increasingly difficult to push through their will and preserve their time-honoured traditions. However, ancient Rome persisted and the Roman way of life did not disappear overnight.

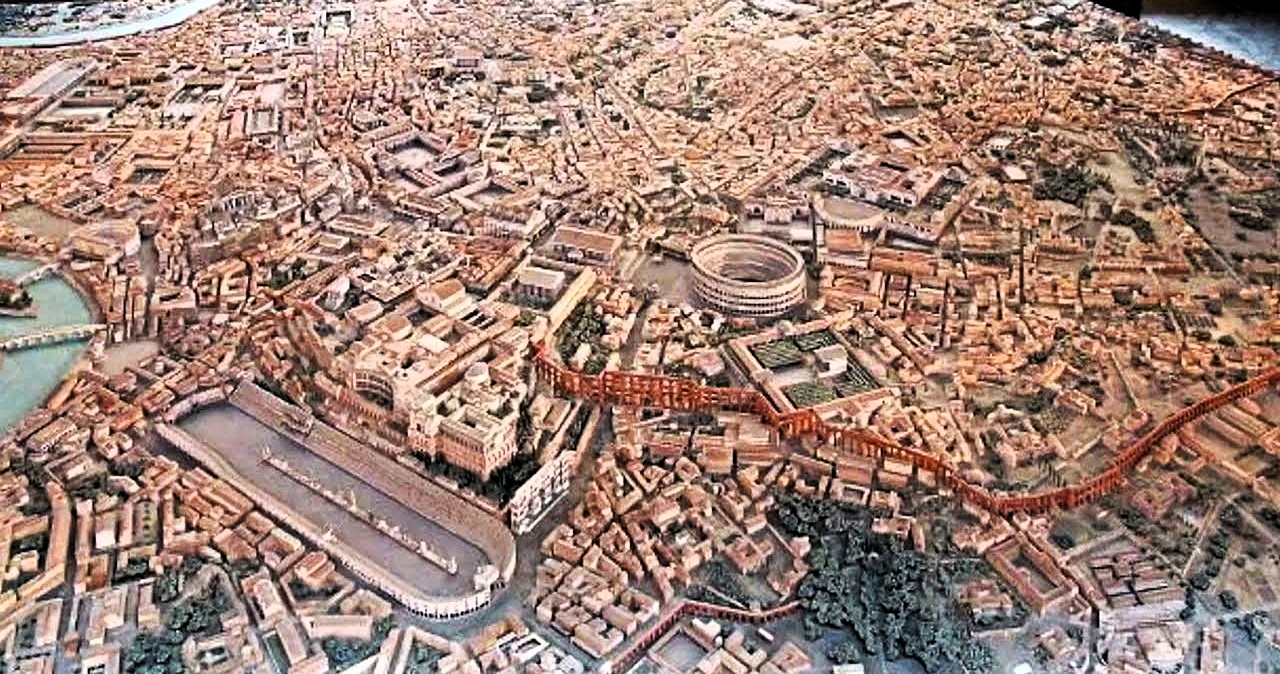

When I several years ago ended up in Rome, I became particularly impressed by the Museo della Civiltà Romana, the Museum of Roman Civilization. An impressive example of fascist architecture that houses, among other very interesting things, a huge model of Rome, as the city appeared in its heyday under Constantine the Great, a time when it contained up to one and a half million inhabitants. The model is accommodated in a bright, airy hall and surrounded by a balustrade from which the visitor, from different angles, can look down on the ancient metropolis.

The museum was funded by the car manufacturer FIAT and was intended to be the culmination of a comprehensive project – the 1942 World Exhibition, which under Mussolini’s aegis began to be planned in 1933 and planned to include a number of imposing buildings and parks. However, the war disrupted it all and the whole thing came to lie half-finished and fallow until several of its structures were completed in the 1950s, including the Museum of Roman Civilization, which was inaugurated in 1955. To my great disappointment, this magnificent museum, with its multitude of imaginative models of buildings and Roman interiors, has been closed since 2014. Almost every year it is announced that the museum will reopen, but it never seems to happen.

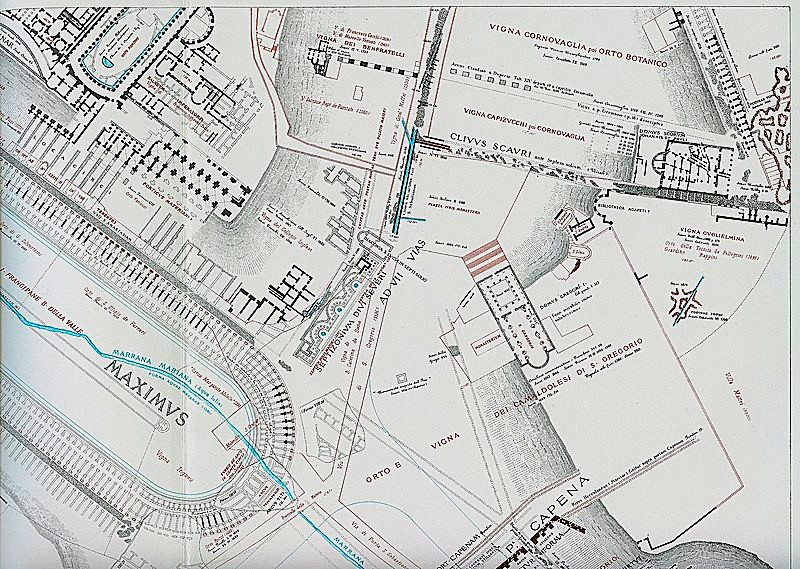

The model of ancient Rome was created by the architect and archaeologist Italo Gismondi. The complicated work was produced on a scale of 1:250 and made of “alabaster plaster”, with reinforcements of metal and plant fibre. The work was begun in 1933, continued during the war and was not completed until the museum's inauguration in 1955.

The large model became Gismondi's life achievement. He had for several years devoted himself to making models of ancient cities and buildings, and participated in excavations, especially in Ostia, but also in North Africa.

His work on the city model was based primarily on the published plans of the archaeologist Rudolfo Lanciano, who by the end of the 1800s had carried out careful measurements throughout Rome and then constructed detailed maps of the ancient metropolis, published in several volumes, the comprehensive bibliography listed a vast amount of ancient and modern maps and texts. The Forma Urbis Romae published by Lanciano in 1901 is considered to have been epochal in terms of ancient topography.

Gismondi supplemented Lanciano's work with his own measurements and included new archaeological finds. An important part of Mussolini’s revival of the “ancient Roman spirit” was to finance extensive excavations, and for a time one of the highlights of fascist propaganda was Mussolini’s almost annual publication of findings from and the festive opening of a new archaeological site.

Through its meticulous reproduction of ancient Rome Gismondi’s model is unusually fascinating. It gives the impression of an exemplary well-ordered metropolis, with gardens, spacious squares, magnificent temples and public buildings, such as the vast public bathhouse with their heated swimming pools, libraries and luxury brothels.

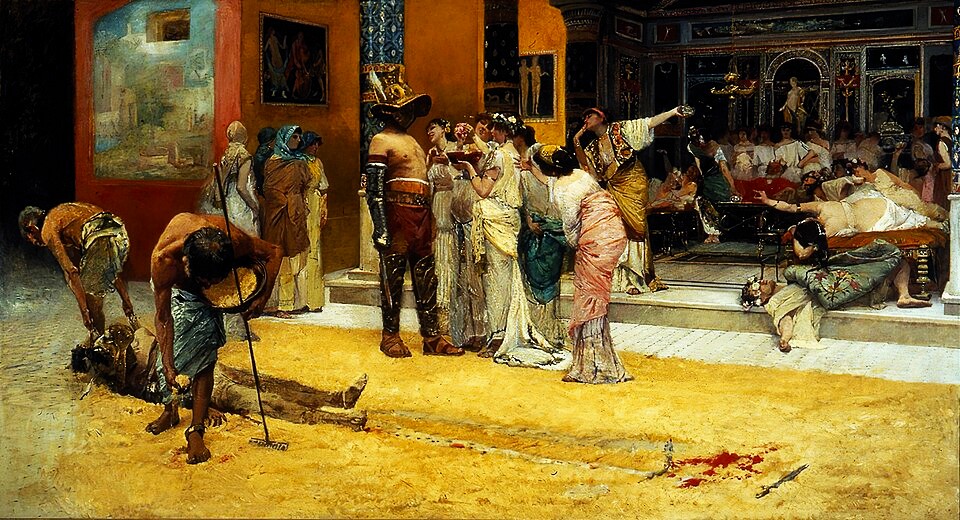

Citizens of Rome could enjoy themselves at racecourses and theatres, or be become incited by the bloody spectacles of the Colosseum. Witing its walls the metropolis has private villas with extensive gardens and every conceivable comfort. In this comfortable environment with running water, cooling fountains, delicious food, flamboyant flowers and exquisite frescoes, its wealthy owners were served by eunuchs and slaves.

Rome still has an extensive supply of running, fresh and tasty water; a multitude of fountains and so-called nasoni, noses, where everyone could take a sip of cooling water during often stifling summer days.

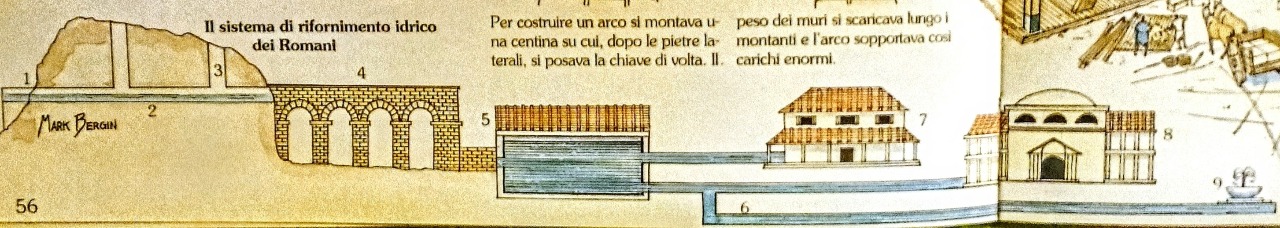

In the time of Damasus, private villas had running water and sewers, while citizens had access to public fountains with drinkable water. A complex system of reservoirs and aqueducts constantly brought water into the city. Below we see how the water up in the mountains was collected in large reservoirs (some of which still exist) and then brought into the city through aqueducts, from where it was carried through underground passages, or pipes, into private houses, bathing establishments and the public fountains that provided common citizens with drinking water.

If the noise and heat of the big city became too unpleasant for them, the owners of the villas could retreat to equally luxurious establishments located on the coast, or up in the refreshing and nearby mountain areas.

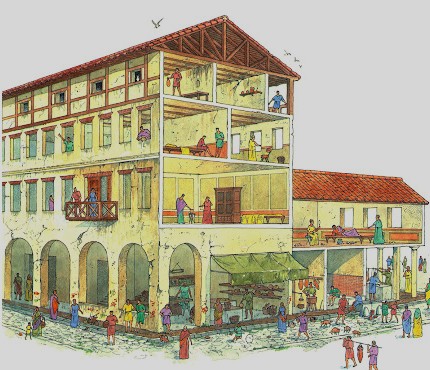

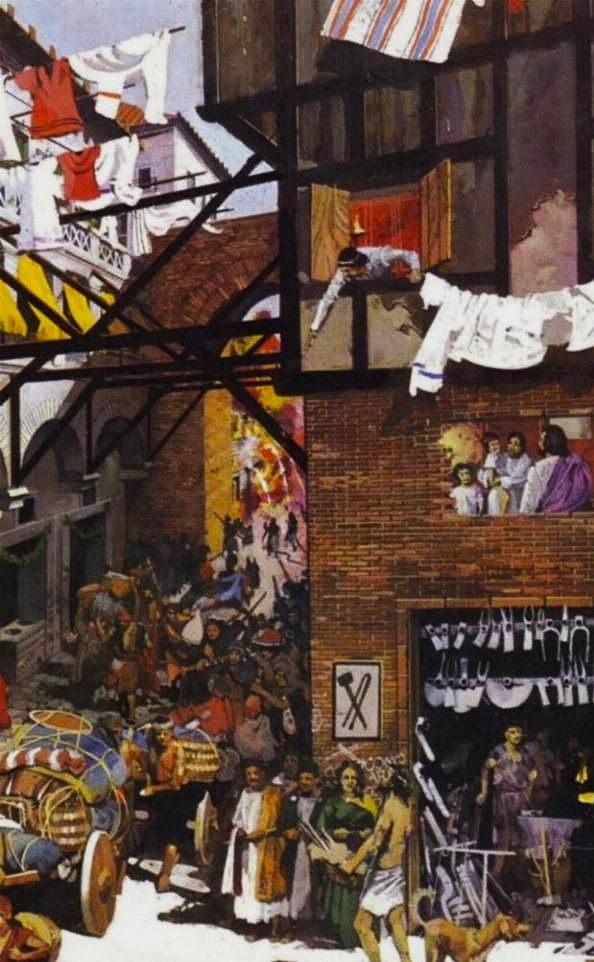

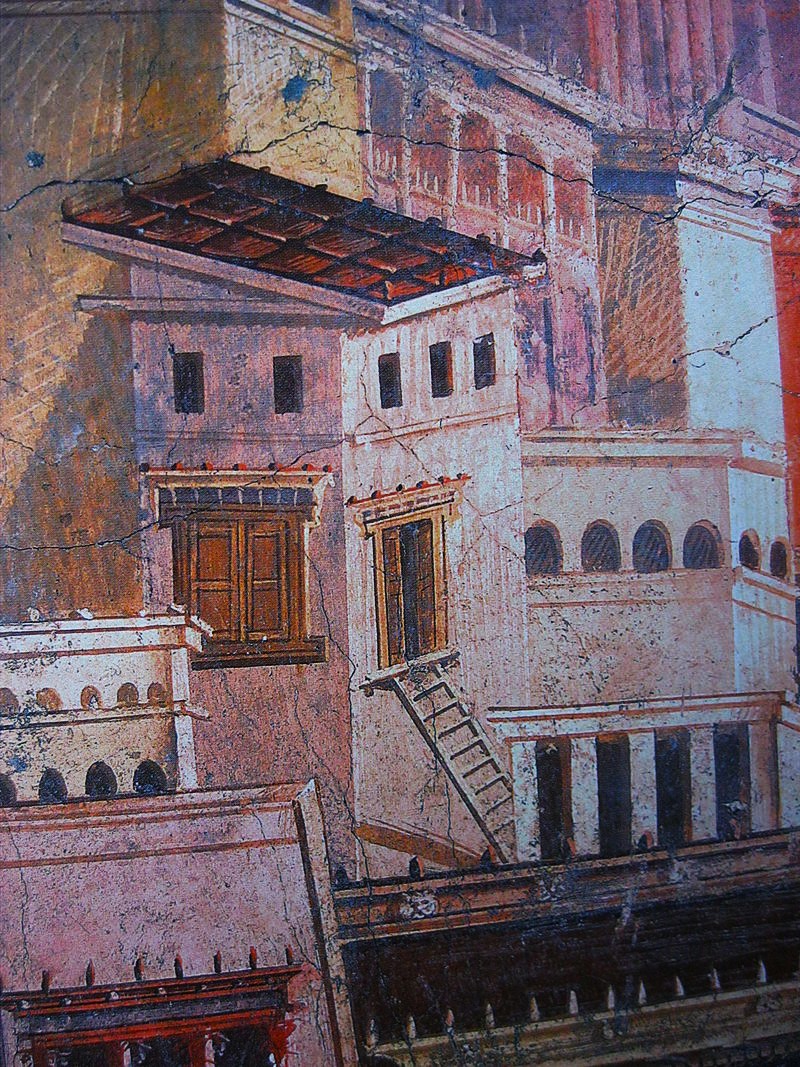

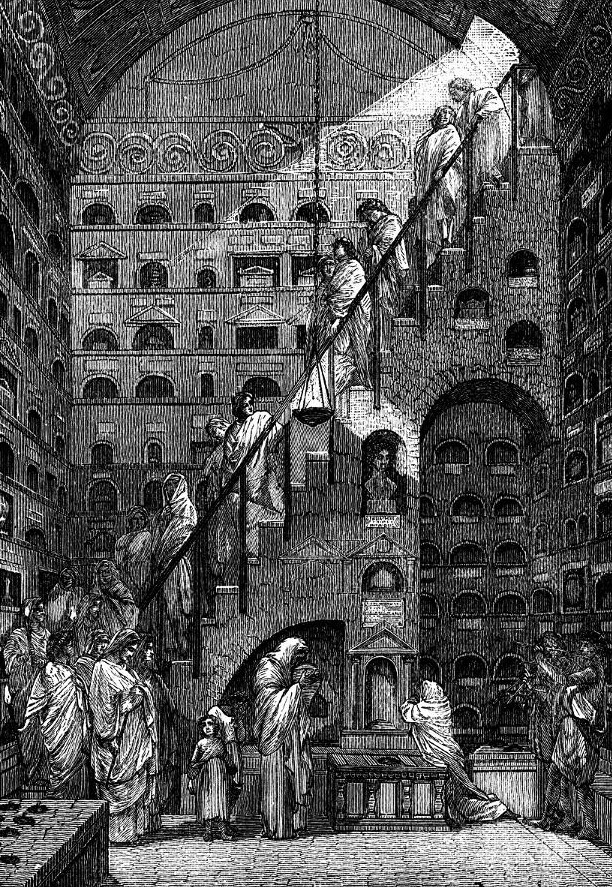

However, in the dense city centre, luxury villas and their large gardens were relatively few. An impression that is effectively conveyed by Gismondi’s model. For the most part, the city was characterized by multi-story apartment buildings, so-called insulae. To control the vast city, keep track of its inhabitants, and as efficiently as possible manage sewage and garbage disposal, its authorities kept relatively accurate statistics and at the time the model depicts, Roman “regional catalogues” counted 46,000 insulae and 1,790 private villas within the city walls.

Insulae were built and owned by wealthy Romans who rented them out as residences, bars, and business premises. Laws limited the height of the houses to a maximum of 20 metres, and their quality varied. There were excellent insulae with running water, sewage, communal gardens, and other amenities, but most of them were generally hastily erected shoddy buildings that housed less well-off tenants. The often extensive residential buildings were built with timber, bricks, and so-called Roman cement, a mixture of slaked lime and volcanic ash, interspersed with stone. This cement, Opus caementicium, has proven to be unusually durable, though Roman writers such as Juvenal (c. 55–140) pointed out that the insulae were often of poor quality, which meant that these buildings occasionally collapsed and that the fire hazard was always great in Rome, especially since the upper floors of the insulae, for reasons of weight and economy, were generally made of wood and with a cement mixed with straw. It was in these dens, which were unbearably hot in summer and freezing cold in winter, that the city's poor population, the plebs, lived (if they were not slaves).

The fire danger forbade cooking and open fires within the insulae, and their tenants generally ate in the many bars and taverns were located on the lower floors and thus lined the streets of Rome.

Violent fires were a constant danger in the densely populated Rome. Each region therefore had its permanent squad of Vigilis Urbani, City Watchmen, or as they were also called Cohortes Vigilum, Guard Troops. They were more than six thousand men, all freed slaves, divided into seven units, each commanded by a centurion, who in his turn was responsible to the city's Preafectus Vigilum, an Equestrian, a term that generally designated a wealthy person who had served as a cavalry officer in the Roman army.

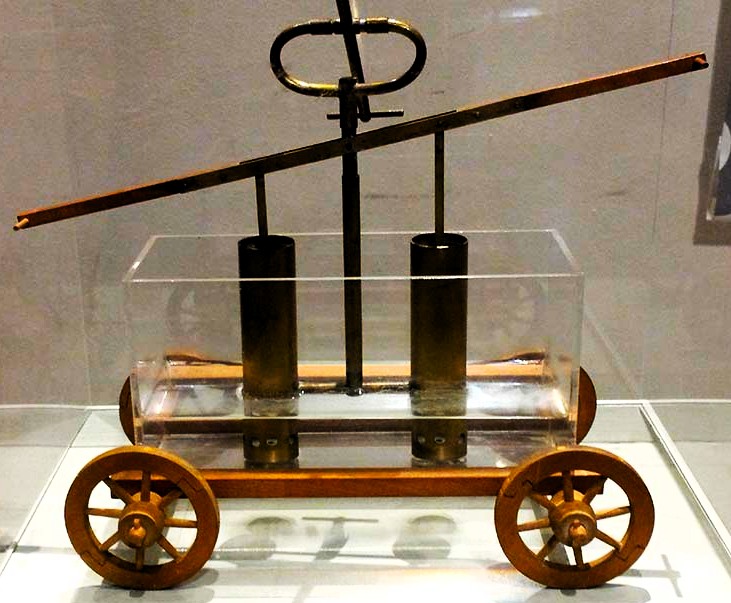

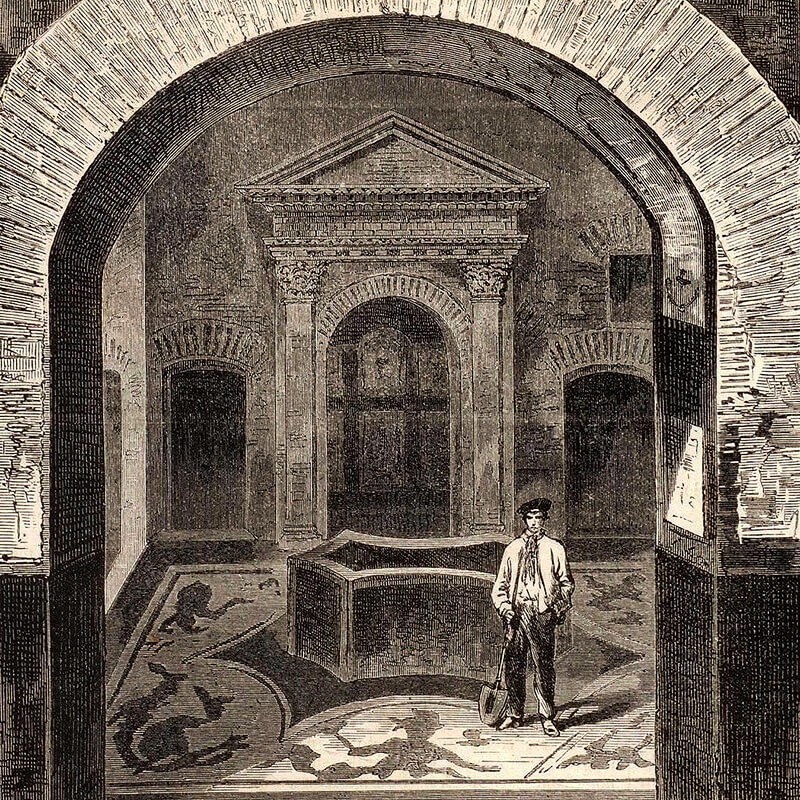

Equipped with a sipho, an occasionally horse-drawn water pump with a container, and carrying large buckets, the vigili would at short notice emerge from their excubitorium, where they had bided their time in their own rooms, often with attached kitchens and bathing facilities. A fairly well-preserved excubitorium complete with a kitchen, a well and a communal room can still be visited, although a previously intact mosaic floor was broken up by the end of World War II and carried away by an unknown group of German soldiers.

The armed vigili also had other duties than firefighting. At night, they patrolled Rome’s streets and alleys in search of thieves and assailants. Rome was in great need of an effective police force. During the day, the city, with its intense street life, temples, arcades, libraries, bustling commerce, various entertainment and parks, could appear to be extremely diverse and alive. It has by contemporary writers actually been described as a metropolis of light, beauty and intellectual vigour, that is if you disregard the brutally insane torture and bloody spectacles of the Colosseum, or the often ruthlessly cruel treatment of slaves.

Humanity and concern for the fate of slaves were not particularly strong among the ancient Romans. The admirable, stoic writer Seneca, who in his writings appears as a good and sensible man, not the least a master when it came to comforting a good friend with well-chosen words he had lost someone close to him, could nevertheless laugh heartily when some condemned wretch fought for his life in the blood-soaked arena. And the good-natured, excellent poet, truth-teller and bon vivant Horace wrote

When your prick swells, then, and a young slave girl or pleasant boy is nearby and you could grasp that opportunity, would you rather burst with desire? Not I – I love the sexual pleasure that’s easy to obtain.

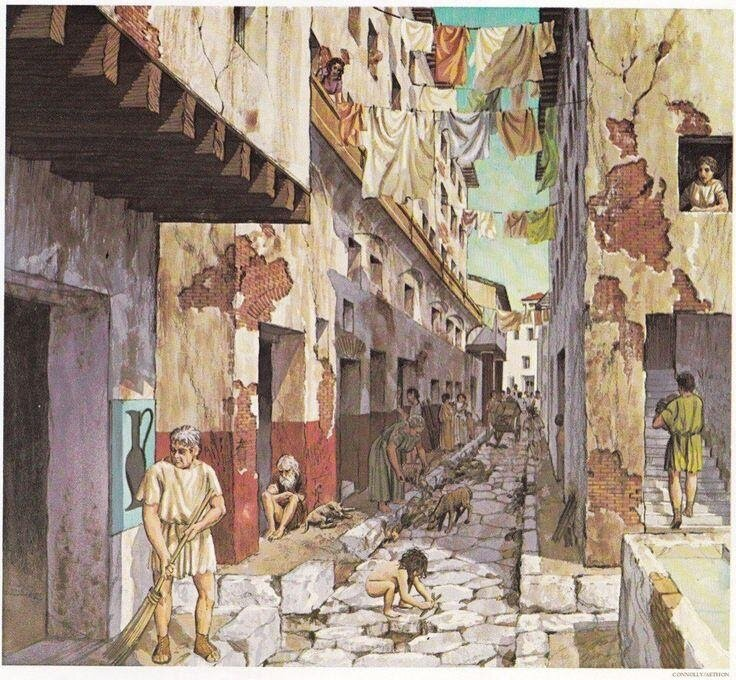

As Roman night fell over narrow, unlit alleys, all the cats turned grey, and few wealthy Romans ventured out between the tall buildings, except in a litter surrounded by a heavily armed escort and torchbearers, while poorer citizens were forced to grope their way through stinking alleys, under leaking aqueducts, and with potential perpetrators lurking around every corner. At best, a patrol of vigili would appear and rescue some distressed wretch by overpowering the occasional villain, who could later be thrown to the hungry beasts of the arena.

In his Third Satire, the excellent Juvenal recounted a conversation he had with a friend he met in the street. The friend, Umbricius, intended to move to the quiet little coastal town of Cumae and Juvenal congratulated him on his decision, pointing out that he himself would be pleased if he could retire on a remote, quiet island, where he would be free from worries about fires and collapsing buildings, as well as from the rouges from the gutters the notorious Suburra quarter, located just behind Forum’s well-swept and patrolled temple area.

In satire after satire Juvenal laments both the city’s poor and its rich citizens, their immorality, superstition and greed. Opinions he shared with his friend Umbricius, who agreed and complained

There’s no joy in Rome for honest ability, and no reward any more for hard work. My means today are less than yesterday, and tomorrow will wear away a bit more, that’s why I’m resolved to head for Cumae […] while my white-hairs are new, while old age stands upright, […] and I can still walk on my own two feet, without needing a staff in my hand, I’ll leave the ancestral land. […] Let the men who turn black into white remain, who find it easy to garner contracts for temples, and rivers, harbours, draining sewers, and carrying corpses to the pyre. Who offer themselves for sale according to auctioneers’ rules. Those erstwhile players of horns, those perpetual friends of public arenas, noted through all the towns for their rounded cheeks, now mount shows themselves, and kill to please when the mob demand it with down-turned thumbs.

Umbricius continued to grumble about the lousy tastes of the times. He claimed to never been lying to himself and others and could not agree when charlatans claimed that a lousy book was good. He did not believe in silly stuff, like believe the stars control of any wretch, or that you can read your future in the guts of a frog.

I must leave it to others to carry to a bride the presents and messages of a paramour. No man will get my help in robbery, and therefore no governor will take me on his staff: I am treated as a maimed and useless trunk that has lost the power of its hands.

Umbricius is not interested in any “bum-boys”. Did not ask how many slaves someone owned, how many acres of land he had inherited or bought, how extravagant dinners he could offer, how many dishes were served, how many coins he hid in his treasury. Like his friend Juvenal, Umbricius placed a large part of the blame for Rome's decline on the immigrants from all corners of the Empire. Both were jealous of and angry at Egyptians and Greeks and not the least at all the licentious women and promiscuous homosexuals they considered themselves to surrounded by. According to them, there was no longer any upright demeanour around, no order, no solid Roman virtues, no morality, no steadfast manhood.

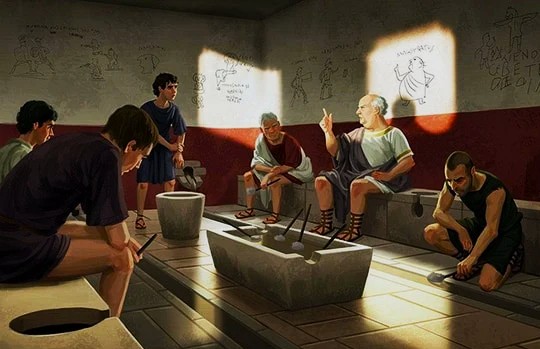

Umbricius began rambling about the crowding and noise of the streets of Rome, where he was forced out after a miserable night's sleep – only emperors and the wealthy people could have a good night’s sleep in Rome, protected as they were behind their garden walls. Day and night, heavily loaded carts with iron-shod wheels rattled through the cobbled city street. Laws restricted the traffic of heavily loaded carts during the day, but exceptions were plentiful and daily restrictions meant that the night traffic became unbearable.

Most sick people here in Rome perish for want of sleep, the illness itself having been produced by food lying undigested on a fevered stomach. For what sleep is possible in a lodging? Who but the wealthy get sleep in Rome? There lies the root of the disorder. The crossing of wagons in the narrow winding streets, the slanging of drovers when brought to a stand. […]When the rich man has a call of social duty, the mob makes way for him as he is borne swiftly over their heads in a huge Liburnian car. He writes or reads or sleeps as he goes along, for the closed window of the litter induces slumber. Yet he will arrive before us; hurry as we may, we are blocked by a surging crowd in front, and by a dense mass of people pressing in on us from behind: one man digs an elbow into me, another a sedan-pole; one bangs a beam, another a wine-cask, against my head. My legs are be-plastered with mud; huge feet trample on me from every side, and a soldier plants his hobnails firmly on my toe. See now the smoke rising from that crowd which hurries for the daily dole: there are a hundred guests, each followed by a kitchener54 […] Newly-patched tunics are torn in two; up comes a huge log swaying on a wagon, and then a second dray carrying a whole pine-tree, towering aloft and threatening the people. For if that axle with its load of Ligurian marble breaks down, and pours its spilt contents on to the crowd, what is left of their bodies? Who can identify the limbs, who the bones? […] See what a height it is to that towering roof from which a potsherd comes crack upon my head every time that some broken or leaky vessel is pitched out of the window! See with what a smash it strikes and dints the pavement! There's death in every open window as you pass along […] you can but hope, and put up a piteous prayer in your heart, that they may be content to pour down on you the contents of their slop-pails!

A fresco from Boscoreale, one of the villages drowned in ash by the eruption of Vesuvius, gives a glimpse of the overcrowding in a Roman city.

There was no limit to the deprivation; drunken scoundrels, who while stinking from beans and sour wine threatened to knock your teeth in, while buffoonish bodyguards and slaves pushed people aside to let their masters' palanquins pass unhindered. Almost all commerce was conducted on and alongside the streets – tabernae filled to the brim with customers as soon as they opened, goods and food were also prepared in stalls that made the streets even narrower than they really were, barbers shaved their customers in the middle of the street, street vendors roamed about with their loads of matches, glassware and pots. They all shouted out about their services and goods. In addition to the tabernae, there were plenty of mobile street kitchens with open fires and boiling water and oil that easily could spill over. Blacksmiths worked at forges and hammered noisily on their red-hot irons, beggars tore at your clothes, snake charmers, fire-eaters, fortune-tellers and all sorts of tricksters performed on street corners and in squares. Juvenal and Umbricius were touchingly in agreement about all the misery that prevailed in Rome.

Add to this the stench from the streets of Rome. It is true that over the years authorities had tried to remedy the runoff of waste and sewage, including through a sophisticated underground sewage system. However, this did not prevent the Tiber from overflowing its banks more often than not and drowning the city's cellars, streets and alleys with foul-smelling water. Men sweated in their woolen robes, a stench that mixed with the scent of oxen and horses pushing overloaded carts, or the fumes of cooking from street food stalls and bars. Not least, there were also the public toilets and urns, which were filled with urine were placed on street corners. In Rome urine was a valuable commodity used for tanning and not least for washing; the ammonia in the urine had a cleansing effect and it was even used as medicine and for brushing teeth.

It was in this vast city with its teeming masses of people, many of whom came from other parts of the world known – such as Egypt, Greece, Syria, Gaul, and Germania – from where they had brought their customs, rites and religious beliefs, that several varieties of Christianity and were practiced, in spite of the fact that the State gave bishops the power to regulate this jungle of schismatic sects and persecute those that did not fit into the official mold.

When Ammianus Marcellinus, 250 years after Juvenal, wrote a history of the Roman Empire of his time, very little seems to have changed in the great city. Ammianus also lamented the vulgar upper class, who continued to indulge in lavish feasts while boasting about their lineage and education, even though the city's libraries were empty “as tombs” and the reading of the wealthy was limited to the popular satirists like Martial and Juvenal. Ammianus's mention of his great predecessor is actually the first time since his lifetime that a reference to his writings has been found.

Ammianus, whose native language was Greek and who found his origins in Antioch, also mentioned that an educated stranger “from the provinces” was at first well-received by the local, wealthy Romans, but when they had found that the stranger lacked wealth, noble ancestry, or good connections within the city's leadership, they turned their backs on him and denied knowledge of any acquaintance with him. Ammianus also had little to spare for the city’s plebs, many of whom during his time were Christians, and who, according to him, were only interested in games and gambling and enjoying themselves, sloppily and vulgarly like the noble Romans whose reserved seats were far up front, on racetracks and during gladiatorial fights.

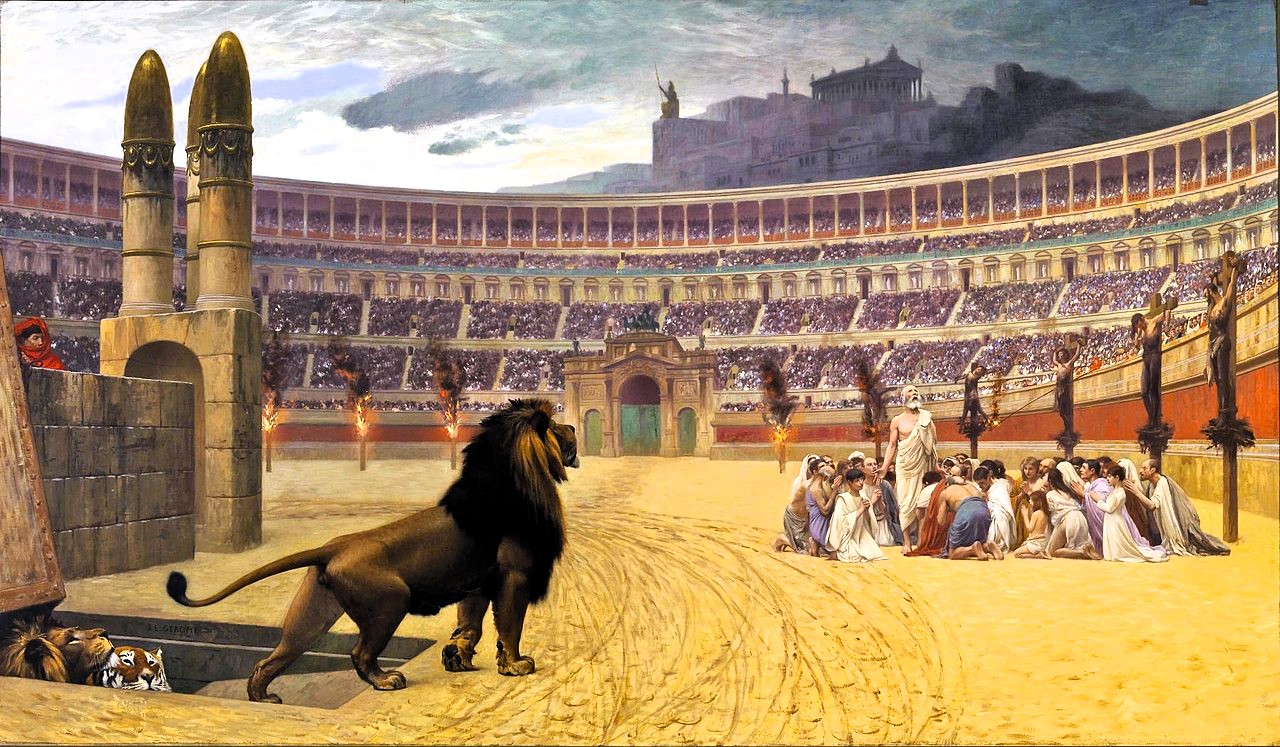

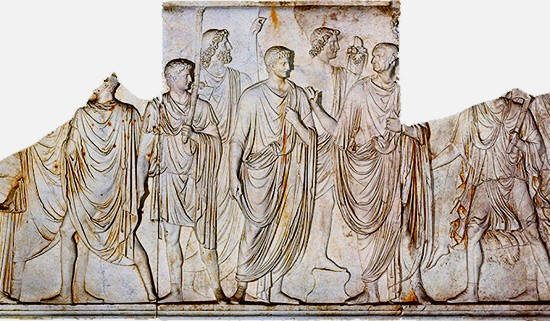

There are a number of misconceptions about the introduction of Christianity in Rome. At school I was taught that its gentle doctrine of love had defeated a crumbling and cruel empire, which, when commanded by Constantine the Great, collapsed like a house of cards. It may be true that Rome during the third century AD had lost much of its power and central position. The emperors no longer lived in the city, but elsewhere in their vast empire, and gradually the Empire had become divided into a western and an eastern sphere, with their own emperors. The western part came to be ruled by usurpers (several of whom had been enlisted mercenaries) who did not find their origin within the original Roman Empire, and the vast city slowly but surely decayed, with a declining population and diminishing importance. However, during the time of Saint Damasus, the Senate still had its seat in the city and time-honoured offices lived on. Sacrifices and complicated rites that had been associated with Roman power for centuries still took place and were attended by large crowds, as did the bloody spectacles at the Colosseum, perverse theatrical performances (the so-called mimes could contain daring nude scenes, as well as the actual torture and execution of criminals) and the wildly popular horse races that took place on several different Roman tracks.

A little over a third of Rome's population consisted of slaves and although the extent of slavery, mainly for economic reasons, decreased over time, it never disappeared completely from what was to become the ruins of the great Empire. During the Christian era, slavery was not at all banned, but was largely replaced by other forms of forced labour, such as serfdom. Few church fathers preached against slavery and Saint Damasus certainly, like most of his contemporaries, regarded slavery as a completely natural phenomenon; as a wealthy Roman citizen, he certainly had several slaves himself.

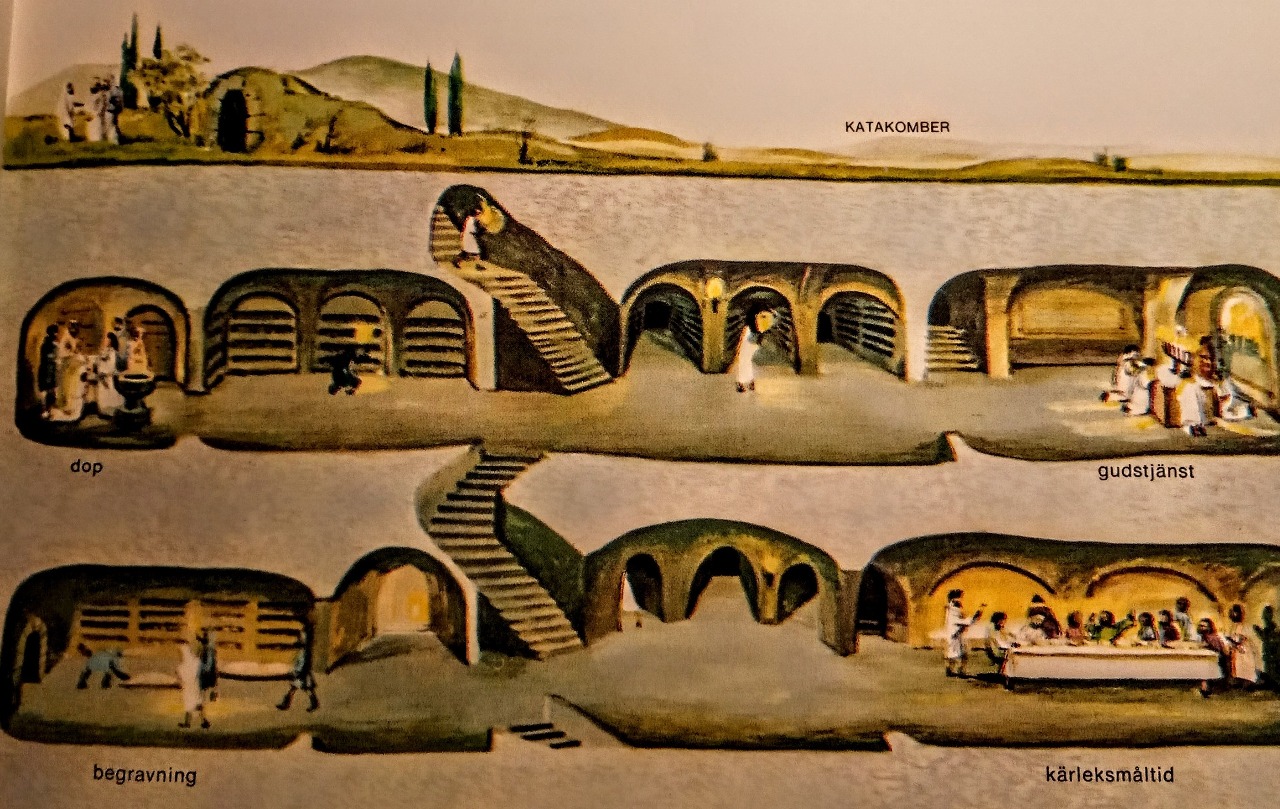

Another popular misconception during my school days was that cruelly persecuted Christians hid in the extensive catacombs outside the walls of Rome. It is true that Christians were occasionally punished and persecuted, up until the Edict of Constantine, but the fact is that by the time of Saint Damasus they constituted a significant and ever-growing minority of the Empire’s inhabitants. It has been estimated that when Emperor Constantine issued his so-called Edict of Toleration in 313, which made Christianity a permitted religion, an estimated fifteen percent, or seven million, of the Roman Empire’s population of 50 million professed Christianity. For various reasons, the Christian religion had grown stronger the during three centuries that followed upon the birth of Jesus. By the time of the Edict of Constantine, Christianity could be described as a state within a state, with an international organization consisting of various bishoprics. As early as around the year 200, the North African Christian teacher Tertullian could argue to the Roman “pagans” that

we are but of yesterday, and we have filled everything you have—cities, islands, forts, towns, exchanges, yes! and camps, tribes, decuries, palace, senate, forum. All we have left to you is the temples!

That Christians “hid” in catacombs is accordingly another myth. These burial grounds were guarded by vigili, and hiding in their underground passages, with limited escape routes, would be a rather foolish strategy. It is true that many Christians were buried in the catacombs, but the main reason for this was not persecution, but the fact that non-Christian Romans generally cremated their dead and stored their ashes in the ground or in special columbaria, of which there were several both inside and outside the city walls. Romans, like Christians, revered their ancestors and could also store their ashes by altar within their houses. Like Christians, they could also hold special “community meals” near their dead ancestors, thereby honouring their memory and showing their communion with them.

The city’s catacombs were all located outside the city walls, and their miles-long underground passages, with niches along the walls, had over centuries been carved out of the soft, volcanic tuff that makes up much of the Roman underground. The niches were often sealed with marble slabs bearing inscriptions and images.

That the catacombs were located outside the walls was due to the fact that Roman authorities, for hygienic reasons, prohibited the burial of intact corpses within the city walls. This had led to not only to Christians, who generally did not burn their dead, but also followers of other religions, such as Jews and Egyptians, had their own catacombs. Some Romans also preserved the corpses of their ancestors, mainly due to family traditions. For example, the influential gens Cornelia did not burn their dead.

Like Romans in their columbaria, Christians held religious rites near their dead and could also arrange ritual meals there (the Romans called such a meal silcernium). Incidentally, it became increasingly common for the Romans after Emperor Marcus Aurelius not to burn their dead and even the law not to bury any corpses within the city walls became relaxed over time, at least among wealthy and influential families, something that the increasingly common and still preserved, magnificently decorated sarcophagi testify to.

That Christians occasionally were persecuted on the orders of Roman emperors was mainly due to the fact that their faith claimed that there was no salvation outside of faith in Jesus Christ, something that the religiously tolerant Roman governmental system regarded as fanatical intolerance and lack of respect for the faith of other people. It is thus easy to imagine why educated Romans, such as the emperor-philosopher Marcus Aurelius, regarded Christians as some kind of fanatically fundamentalist Talibans.

The Christians’ refusal to participate in Roman sacrificial rites and buy the meat they resulted in, was seen as a betrayal of the Roman state, especially as many of these sacrifices involved respect for the emperor's authority, as well as the laws and cohesion of the Empire. Roman power and state-sanctioned religious rites were intimately connected, and a refusal to respect these was by many Roman citizens considered as open rebellion. In the words of Edward Gibbon in his justly famous The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire:

By embracing the faith of the Gospel, the Christians incurred the supposed guilt of an unnatural and unpardonable offense. They dissolved the sacred ties of custom and education, violated the religious institutions of their country, and presumptuously despised whatever their fathers had believed as true, or had reverenced as sacred.

A well-founded view that might be compared with the correspondence between the distinguished emperor Trajan and his good friend Pliny the Younger, in which the latter, around year 110, in his capacity as governor of Bithynia and Pontus (along the southern coast of the Black Sea), wondered what he should do with the growing number of Christians in his domains. Until then, Christianity had the authorities been regarded by as a Jewish sect, and Jews had traditionally been exempted from participating in sacrifices for the emperor's well-being and the preservation of the Empire. Now, however, it had been generally realized, and most Christians claimed it was true, that Judaism and Christianity were two separate religious beliefs. The authorities therefore ordained that Christians, in accordance with Roman law, like other religious practitioners had to participate in sacrifices to the gods of the Empire. Refusing to obey this law could lead to severe punishments, even execution. Pliny wrote:

I have never been present at any legal examination of the Christians, and I do not know, therefore, what are the usual penalties passed upon them, or the limits of those penalties, or how searching an inquiry should be made. I have hesitated a great deal in considering whether any distinctions should be drawn according to the ages of the accused; whether the weak should be punished as severely as the more robust, or whether the man who has once been a Christian gained anything by recanting? Again, whether the name of being a Christian, even though otherwise innocent of crime, should be punished, or only the crimes that gather around it?

Pliny reported that his method consisted of telling the judges to ask a Christian on three occasions whether a/he, by repeating a fixed formula, was prepared to renounce his/her faith. If the Christian refused on the third occasion, s/he was forced to offer incense and wine in front of the emperor's image and then curse the name of Christ. Pliny had found that several Christians were unable to do this and it was first then that he had order them to be punished (he does not mention in what way). Pliny further reported that he had heard that the Christians gathered at dawn and then sang hymns to Christ, as if he was a god. Furthermore, the Christians swore not to commit any kind of crime, including theft and debauchery, and that they had never embezzled money entrusted to them. Their rites seemed perfectly harmless, but since an imperial edict had forbidden “secret societies,” the Christians were considered as such, and their refusal to sacrifice for the emperor’s welfare was undoubtedly a crime. To make sure that other forms of slander against the Christians was groundless, Pliny had two women, “called by them deaconesses,” tortured, but then found “nothing but a degrading superstition, carried to its extreme.” In his answer Trajan wrote:

You have adopted the right course, my dear Pliny, in examining the cases of those cited before you as Christians; for no hard and fast rule can be laid down covering such a wide question. The Christians are not to be hunted out. If brought before you, and the offense is proved, they are to be punished, but with this reservation — if any one denies he is a Christian, and makes it clear he is not, by offering prayer to our gods, then he is to be pardoned on his recantation, no matter how suspicious his past. As for anonymous pamphlets, they are to be discarded absolutely, whatever crime they may charge, for they are not only a precedent of a very bad type, but they do not accord with the spirit of our age.

Active practice of Christian rites at the expense of the emperor's cult, continued to be a serious crime, and the punishment for this varied according to who held the imperial power. In general, it can be argued that it was only in exceptional cases that a Christian was executed, and if this happened, it was generally if a Christian leader openly had preached against the imperial power and actively encouraged his followers not to sacrifice to the Roman gods and/or the image of the emperor. The only large-scale massacre of Christians before the accession of Emperor Decius (apart from short-term persecutions under weak emperors such as Caligula, Nero and Domitian, who used the Christians as scapegoats for their failed policies) had taken place in the Rhone Valley in 177, where rumors had been spread that the Christians had engaged in cannibalistic rites. At that time, the central power had tried to curb the violence.

The beginning of the 3rd century was marked by political unrest within the Empire. Generals had themselves proclaimed emperors and civil wars broke out in various places, while the Germans threatened the Empire's border fortifications. In 249, Emperor Decius tried to bring order by actively forcing all Roman citizens to submit to the emperor's cult and sacrifice to the Roman gods. However, the Christian organization had grown so strong that the occasionally bloody persecution of Christian dissidents proved futile and it ceased after two years. The greatest persecution of Christianity to date then took place under Diocletian, who between the years 249 and 251 also assumed that the Empire would be welded together by a common state-sanctioned religion, based on Roman tradition. However, even this ruthlessly violent attempt to wipe out all religious opposition failed miserably and only resulted in the well-organized Christian church growing even stronger, something that the ruthless realist Constantine, called the Great, realized and managed to use to his advantage.

Constantine made a sensible choice. Favouring Christianity had several advantages that the central government could exploit. First of all, Christianity was universal in the sense that it did not, like most other sects in the Roman Empire, serve an exclusive, initiated society. In principle, all people were welcome into the Christian fold and, as American Express states – membership has its privileges. Christianity had a well-developed charity system and in an otherwise troubled and unpredictable world most Christians felt a sense of belonging to each other. Furthermore, this specific belief system had grown like a seedling on Judaism, which was already widespread and present throughout the Roman Empire, with strongholds in the cities, and united by trade and the exchange of ideas. As was the case within Judaism, the Christian leadership was generally literate and supported by a specific linguistic tradition (initially Greek was the predominant language within the Christian church). Like the Roman state, Christianity was also hierarchically structured, with its deacons, priests and bishops. It was also, unlike other religions, relatively independent and stable in relation to the weakened and to some extent disintegrating state religion. Constantine was also well aware of how steadfast and strong the Christian faith community had proven to be during Diocletian’s harsh persecutions. If he could get this faith and its hierarchy firmly on his side, Constantine understood that his power could be consolidated. The Greek-speaking Church Historian Eusebius (ca. 260-339), who was apparently Constantine's advisor on religious matters, poured in his writings praise on his master whom he called Ho theofilephilestatos basileus, God's most beloved emperor.

Constantine, an emperor and son of an emperor, a religious man and son of a most religious man, most prudent in every way, as stated above - and Licinius the next in rank, both of them honoured for their wise and religious outlook, two men dear to God - were roused by the King of kings, God of the universe, and Saviour against the two most irreligious tyrants and declared war on them.

One of these was Constantine's cousin Maxentius, certainly not one of God’s best children. When he was defeated in the battle of Saxa Rubra and drowned in the Tiber, Constantine had his body retrieved and beheaded, he also beheaded Maxentius’ sons, who according to Roman succession should have become emperors instead of Constantine. He later had his son, Crispus, and his former co-emperor Licinius, who was married to Constantine's sister, executed.

History tells us that Crispus was desired by Constantine’s young, second wife – Fausta, who had driven away his mother Helena. When Crispus refused the advances of his stepmother, she accused him of inappropriate advances and Constantine had his son killed and eventually Licinius as well, since he had told him the truth about Fausta. When Helena, who was a Christian, finally intervened in the family drama and also accused Fausta, Constantine had his wife executed and took his later sainted mother to grace. Eusebius mentions nothing of this, but instead pours biblical flattery on Constantine.

This emperor actually changed the course of history in favour of Christianity. Perhaps it can be said of him that it was his actions, and not those of Jesus and Paul, that made Christianity a world religion. This despite the fact that Constantine throughout his life was a faithful Mithras worshiper and retained his office as Pontifex Maximus, High Priest of the Empire and by virtue of this office performed the state sacrifices for its preservation. Coins minted during his reign bear the inscription Soli invicto comiti, to the Unconquered Sun.

In 321, Constantine banned crucifixion as a punishment and made Sunday a public holiday for the entire Empire, erecting large Christian churches in Rome, one next to his palace on the Lateran Hill and another in the Vatican, the site traditionally considered to be the place of execution and burial of the Apostle Peter.

Churches were also built in the northern city of Trier, where he had once exiled his mother Helena and his son Crispus, in Aquileia, an important port in northern Italy, in the episcopal sees of Antioch and Alexandria and not least a stately church above the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem and one in Constantine’s new capital – Constantinople. The presbyters, Christian priests, were exempt from taxes and allowed to freely use the Empire’s postal and communication system, which was unusually efficient and well-developed. For example, Marcion (c. 85-160) an early Christian, or rather a Gnostic under Christian cloak, travelled between Phrygia (located in present-day central Turkey) and Rome no less than 72 times.

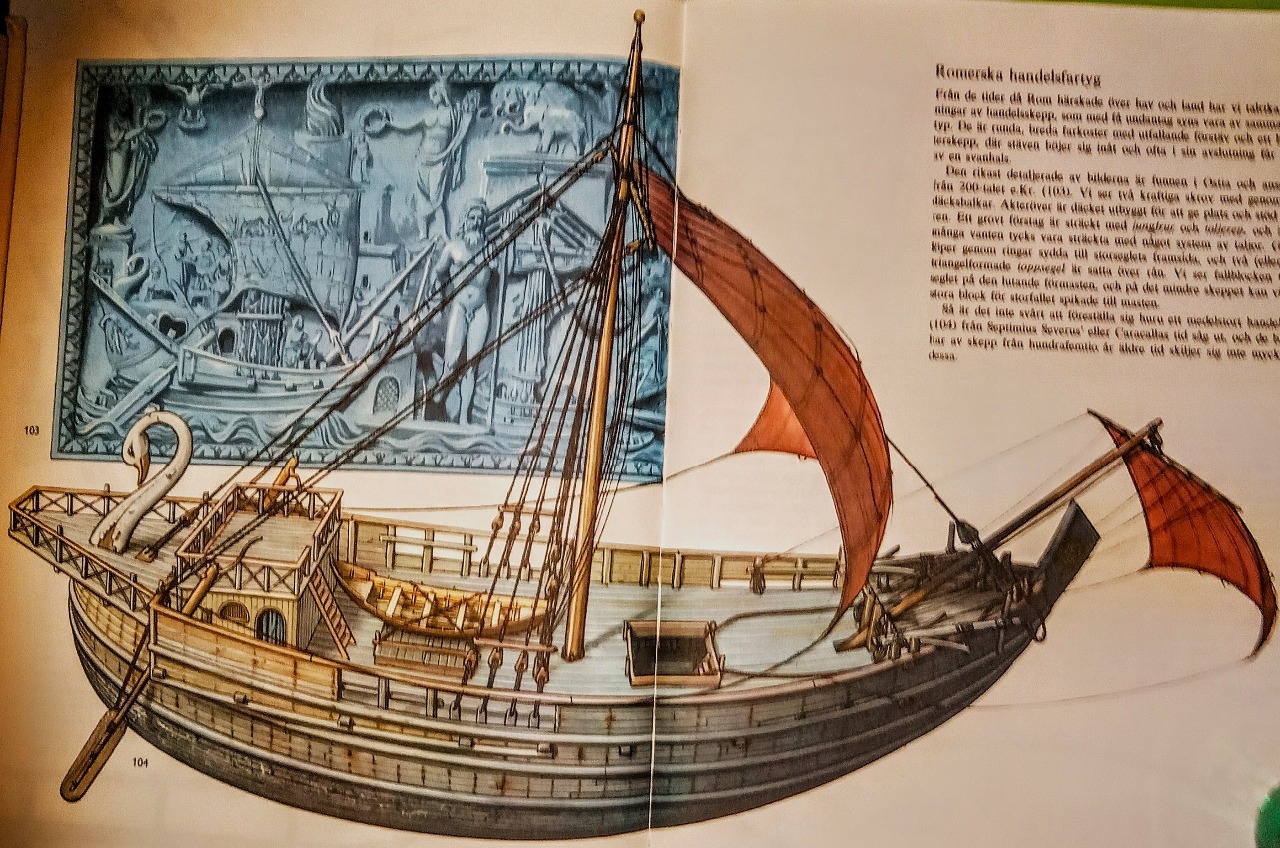

Maritime traffic across the Mediterranean was also lively and the exchange of goods was large, both by sea and by land.

This was one of the reasons why Constantine, in his attempts to unify the Empire, was able to convene extensive synods with participants from all corners of the Empire. For example, the Council of Nicaea in 324, an initially futile attempt to unite the conflicting teachings that threatened to tear apart the religion that Constantine apparently hoped would become the unifying glue of his Empire and perhaps even replace the increasingly weak state religion, which despite its connection to the state administration had increasingly lost its strength and prestige. Perhaps Constantine was also influenced by his mother Helena and possibly also tormented by a guilty conscience for his sins, such as the rash murder of his son. Unlike the Roman religions, Christianity propagated the forgiveness of sins. In any case, Constantine had himself baptized on his deathbed.

Constantine was far from being a saint even if many Christian apologists have tried to depict him as such. However, I assume that Jacob Burchardt who in his 1853 excellent book The Age od Constantine the Great depicted him as a cruel and ambitious politician was probably right

In a genius driven without surcease by ambition and lust for power that can be no question of Christianity and paganism, of conscious religiosity or irreligiosity, such a man is essentially unreligious, even if he pictures himself in the midst of a churchly community. Holiness, he understands only as a reminiscence or a as a superstitious vagary. World-embracing plans and might dreams lead him by an easy road to the streams of blood and slaughtered armies.

Constantine had moved the capital of the Empire to Constantinople, which he had founded, and although Rome still retained its character of a multifaceted metropolis so vividly described by Juvenal, where the Senate still exercised formal power and a deputy Pontifex Maximus appointed by the emperor performed the state sacrifices, the city slowly but surely slipped into a backwater. Christian potentates waited in the wings, wishing to usurp absolute powers, still subject to the increasingly distant emperor, but freed from the Senate and the impious, demonic, Roman sacrificial cult and its plethora of pagan, unsavoury divinities. The bishops of Rome wanted to wear the gold and purple of power, be hailed as God's representatives on earth and ... why not? collect gold and enjoy the favour of women.

After his service an old warrior had settled in Rome. The Greek-speaking Ammianus Marcellinus had previously been a high-ranking officer, being Protector domesticus on the staff of several emperors, especially Julian, whom he seems to have known personally. Emperor Julian has gone down in history with the epithet The Apostate, because when Christianity had become almost exclusively dominant, he tried to reintroduce the traditional Roman cult and favoured Judaism at the expense of Christianity.

Julian regarded Christianity as a crude, fundamentalist ideology that stifled classical education and despised all other religious expressions. He did not persecute Christianity, but wanted to remove the privileges it had been granted and was zealous for religious freedom under the traditional Roman system.

Emperor Julian is undoubtedly the hero of the history that Ammianus wrote in Rome. Ammianus was not a Christian. He considered Christianity to be mundane and simple. In spite of believing in fortune-telling and auguries, Ammianus seems to have had a gnostic worldview. Tolerant and generally sympathetic, he wondered how Christianity, with its doctrine of love, nevertheless was governed by a multitude of potentates who ruthlessly fought their fellow believers to obtain positions of power while attacking other beliefs, especially those that flourished within the sphere of Christianity. According to Ammianus Constantine had unnecessarily complicated the conflicts within the Christian sphere when he, through his synods drew attention to meaningless hair-splitting disputes over details of the faith. As the old soldier he was, Ammianus did not pay much attention to the internal strife of Christianity, and if he did, he could occasionally interrupt himself with phrases such as "Enough for now with city affairs. Let me return to the events that unfolded in the provinces." With this Ammianus generally meant the ifferent battles waged along the Empire’s frontiers, some of which he had participated in.

During Ammianus' time in Rome, the city's rulers were still pagans. For example, the classically educated, wealthy, eloquent and generally respected Aurelius Symmachus, who in 384 was elected Praefectus urbi with responsibility for the administration of Rome, fighting for religious freedom and tolerance. Ammianus praised Symmachus as a man of "exemplary learning and good judgment" who created peace and order around him. This did not prevent Christian “ruffians” from spreading malicious rumours about him, with the result that a misguided mob burned down one of his villas (the Symmachus family owned several residences in different parts of Rome).

As a powerful opponent, Symmachus had the skilled, energetic and religious bishop of Milan, who was closer to the Christian imperial power, which at that time was based in Milan. The educated and ascetic Ambrose was a deeply convinced Christian who vigorously battled what he considered to be dangerous deviations from the Christian faith he had chosen to support. The strict Ambrose became known as “the scourge of God”. The Hungarian writer Tibor Déry, who after having been a communist changed his ideology and after the Hungarian uprising in 1956 was sentenced to nine years in prison. Déry thus knew a lot about totalitarian thinking and the exercise of power. He wrote a novel about Ambrose that in Swedish has the aforementioned epithet as its title. It was an allegory of how total power – over human thinking and state governance – emerges victorious from the battle against tolerance and freedom of thought.

The novel deals with, among other things, how the quiet Symmachus, shortly after being appointed as prefect of Rome, appealed to Ambrose to respect Roman traditions. Symmachus knew Ambrose personally and had once even recommended the eventually extremely influential Saint Augustine of Hippo as a student to him. Augustine, who at that time was a Manichaean, a follower of a strictly ascetic, dualistic religion, would become, under the influence of Ambrose, a deeply serious Christian and one of the greatest theologians of the Christian church.

The most famous doctrinal dispute between Symmachus and Ambrose concerned the altar in front of the Goddess of Victory that for centuries had watched over the meetings of the Roman Senate. Symmachus pleaded and prayed that this altar be preserved, as well as the traditional rites that opened Senate meetings and the oath the senators swore to act in accordance with the will of the gods and for the good of the people. Christian senators had demanded that the altar must be destroyed and some of them, like Bishop Damasus, refused to enter the Curia as long as the altar remained. Symmachus asked Ambrose (they were related) to convince the emperor that the altar must be preserved:

For, since our reason is wholly clouded, whence does the knowledge of the gods more rightly come to us, than from the memory and evidence of prosperity? Now if a long period gives authority to religious customs, we ought to keep faith with so many centuries, and to follow our ancestors, as they happily followed theirs. […] We ask, then, for peace for the gods of our fathers and of our country.

Ambrose, on the other hand, believed that the teaching of Jesus Christ and the fact that faith in him saved us from all the evil that has preceded us and this conviction had to be safeguarded from the veneration of the false gods that Jesus once and for all had exposed as non-existent. It was high time to free ourselves from all these meaningless, obsolete, and downright demonic rites. Symmachus replied:

It is just that all worship should be considered as one. We look on the same stars, the sky is common, the same world surrounds us. What difference does it make by what pains each seeks the truth? We cannot attain to so great a secret by one road; but this discussion is rather for persons at ease, we offer now prayers, not conflict.

That kind of tolerance was unacceptable to a Christian prince like Ambrose. Hadn't Jesus said: “I am the way, the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me?”

The altar was removed and the emperor ensured that the tax money that paid for the ceremonies of the Senate and the Roman state would immediately cease to be granted, all religious practice was now under the protection of the Catholic Church and all religious power would henceforth rest in the hands of the enterprising bishops. Their power grew ever stronger (although Damasus died in 384, the same year the altar was removed). The further fate of the statue of the goddess of victory is unknown, after a while she was probably broken into pieces.

Symmachus can be considered as leader of the conservative Romans, fighting in vain against an increasingly dominant Christian church. Symmachus' defeat was not final, nevertheless it can be argued that even if Christianity originated in Palestine, the Christian faith was to a large extent created in Rome. It was in Rome that much of Christ’s message was transformed into a guarantor of the rule of worldly power. In fact, the Rome that Symmachus believed he was defending against Christianity did not disappear. Rather, Christianity was adapted to Roman power and its traditions. In any case, ancient philosophy and its religion did not die through any fatal blow. Rome lived on, albeit under new forms and the transformation took a long time. Symmachus died honoured by his faithful. In a contemporary ivory image, we see him sitting on a chariot harnessed to elephants while his soul is being carried from a funeral pyre (his earthly remains were burned in accordance with pagan tradition) by winged creatures to the heaven of the ancient philosophers.

It was not only the battle against Symmachus that strengthened Ambrose's positions. In 388, a Christian mob had attacked a synagogue in the Syrian city of Callinicum. They had beaten up members of the Jewish congregation and finally burned down its synagogue. Emperor Theodosius had claimed that Jews, like Christians, were under the protection of the state and thus forced the local bishop and his congregation to replace the Jews and rebuild the synagogue at their own expense. When Ambrose heard this, he was outraged. Like several of his fellow believers, he had begun to propagate the myth that the Jews, as an entire people, were guilty of Jesus’ death, and in his sermons, he attacked Theodosius as a traitor to the Christian faith.

A misdeed on the part of the emperor meant that Ambrose finally managed to break Theodosius and convince him to issue an edict that banned the practice of all religions except Christianity. Ambrose reluctantly agreed to exempt Judaism from the ban. The reason was that in 390 a Roman general of Gothic origin in Thessalonica had imprisoned a popular charioteer on charges of sodomy. When the general refused to yield to people’s demands for the charioteer’s release, he was lynched. The murder of a Roman commander outraged the emperor to such an extent that when the city's racing fans gathered in the arena for a new competition, the exits were blocked and imperial troops, a large part of whom were Goths, went wild on the audience, slaughtering men, women and children. It was said that seven thousand people lost their lives in the bloody massacre. Both the figures and the sequence of events have later been questioned, though there is no doubt that a massacre took place and although Theodosius’ guilt has also been questioned, he nevertheless took responsibility for the ferocious deed. When Ambrose was reached by the terrible news, he excommunicated the emperor and forbade him to participate in the Eucharist. Faced with violent opposition, Theodosius was forced to seek out Ambrose in Milan and ask forgiveness for his sins. A very notable event that was taken as corroboration of the Church’s power over the emperor.

When this was happening, the external threat from the Goths, Franks, Vandals and Huns was constantly increasing, while within the Empire the strife continued between different pretenders to the throne and schismatic faiths. The times were extremely turbulent and prophets of doom were plentiful. Soon the Goths and other “barbarians” would break through the border fortifications and spread death and misery around them.

Parenthetically, Julian the Apostate has also been the subject of a novel, which like Déry’s book provides a fine depiction of the world in which Saint Damasus moved. Gore Vidal’s Julian does like Ammianus provide an appreciative portrait of the last pagan emperor, an advocate of classical education and tolerance. Vidal’s portrayal of Julian is in accordance with Vidal’s own disposition an advocate of tolerance, specifically towards homosexuality.

Against this background, Saint Damasus, like Symmachus, appears to be an advocate of a powerful Rome, but on completely different grounds. Everything suggests that Damasus’ zeal for Rome to remain a centre of power had personal reasons. He wanted to seize power and prestige by emphasizing Rome's Christian foundations as the city where Paul and Peter had chosen to work and where they had met their death, as had so many other champions of the Christian faith. Damasus main argument for Rom’s pre-eminence was that Jesus had chosen Peter to lead his Church:

“Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah. For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my heavenly Father. And so I say to you, you are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church,* and the gates of the netherworld shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys to the kingdom of heaven. Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven; and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”

As bishop of Rom’s congregation, Damasus aspired to succeed Peter as lord of all Christendom. He therefore favoured the worship of Peter and Paul. The great basilica over the tomb of Peter that Constantine had begun was completed in 368, two years after Damasus became bishop, and he himself initiated a number of church buildings. Foremost among them was the Basilica of San Lorenzo that Damasus had built next to his villa in central Rome. As soon as I heard about this church, I went there and found to my surprise that it was invisible from the street, built as it is within the impressive Palazzo della Cancelleria, erected around the church in 1495. The palace is still the location of the Vatican’s Supreme Court.

You enter through a discreet side door and once inside, a large, baroque church opens up. Not much remains of Damasus' original basilica, which he dedicated to the martyr San Laurentius, patron saint of the church by which he himself was born and where he served as a priest in his youth. Under the altar of the new church are some remains of Saint Damasus, other parts rest in the Vatican.

It cannot be denied that I was somewhat disappointed to find that there were not so many traces of the original basilica of Damasus, which so many other Roman church buildings over time had been drastically changed and rebuilt in accordance with the tastes of other times. However, like most other Roman buildings, San Damaso in Lorenzo also had its fascinating secrets. Under the church are not only the remains of a Mithraic temple, but also a three to six metres deep underground lake, with emerald green water.

The lake was formed when a stream called Euripus was diverted, to supply water to the nearby Agrippina Baths. At that time, the Euripus flowed along the surface of the ground, but now it flows under Rome. Several sarcophagi had been placed along the Euripes and some of them can still be seen under Rome, including under the Palazzo della Cancelleria, for example the sarcophagus of Aulus Hirtius, a centurion in Caesar's army.

Up in the church is a fresco by a relatively unknown nineteenth-century artist named Luigi Fontana depicting an important episode in the history of the Catholic Church – Saint Damasus receiving the Vulgate. Sometime in the early 380s, Damasus had employed Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus as his secretary. Hieronymus was born in Stridon, a small town in what is now Slovenia, and had previously studied in Rome before going to Syria where he tried to live as a Christian ascetic, but after a while he gave up this self-torture and returned to Rome where Damasus became interested in his knowledge of Hebrew.

Hieronymus had been taught Hebrew in Syria and continued his studies in Rome under a Jew who had converted to Christianity. Since Jerome was also fluent in Latin and Greek, Damasus commissioned him to translate both the Old and New Testaments into Latin. The New Testament was written in Greek and the existing Latin translations were rather poor. The so-called Septuagint version of the Old Testament used by Christian congregations was a Greek translation, made during in the 1st century BC by Jewish scholars in Alexandra. According to Damasus, the Old Testament should now also be translated into Latin and then directly from the Hebrew, but not by any Jews, whom he suspected were inclined to falsify it.

This vast translation enterprise was part of Damasus’ effort to free the Roman Church from the “Greek yoke.” Christianity was to be Latinized and power would thus rest securely with Peter’s successor, i.e. the Roman bishop, a position now held by Damasus. Damasus ordered that from now on the Christan mass had to be celebrated in Latin, and not as before in Greek. This view was one of the reasons why Damasus did not attend the Council of Thessalonica in 380, when Emperor Theodosius issued his edict that made Catholic, Nicene Christianity the state church throughout the Roman Empire. All other Christian faiths were thus condemned, such as Arianism, described as dangerous heresies being spread by “foolish madmen”. The edict declared that all beliefs that did not fully conform to the Nicene Creed would be severely punished.

Damasus fully agreed with that part of the edict, but objected to the fact that the council had taken place in the eastern part of the Roman Empire and not in its former capital, where the Holy See of Peter was located, and that the meeting thus had been dominated by Greek-speaking prelates.

The edict declared that “the bishop of Constantinople shall have precedence in honour after the bishop of Rome,” a formulation that made Damasus furious

What precedence? Rome's primacy is in no way connected with Rome’s past as the capital of the Empire, but is based exclusively on its apostolic right, its descent from Saints Peter and Paul. Constantinople does not have any second rank in terms of any primacy. The city is not even a patriarchate. Constantinople is of lesser importance than both Alexandria and Antioch. The former congregation had been founded by Saint Mark on the orders of Saint Paul, and Saint Peter had been bishop of Antioch before he went to Rome.

By “patriarchate” Damasus meant the “apostolic sees”, i.e. congregations founded by apostles, to which only Rome, Alexandria and Antioch were counted.

However, Damasus could console himself with the fact that the edict appointed him as Pontifex, that is, that his office replaced the emperor’s traditional right to act as Pontifex Maxiumus, i.e. High Priest of the entire Empire, with both religious and political obligations. It can thus be argued that Damasus became the first pope, but it was his successor, Siricius, who was the first bishop to be granted the title “Pope”, from the Greek páppas, father. Previously, all bishops had been titled páppas, but now only the bishop of Rome was allowed to referred to in this way. However, the title “Pope” was not officially established until the first millennium.

.jpg)

The fresco in San Damaso in Lorenzo does not correspond to reality. Damasus did not live to see the completion of the Vulgate; it was unfinished when he died in 384, the same year that its translator Jerome was forced to flee Rome after rumours of his inappropriate behaviour towards the city's wealthy ladies, something I intended to write about in a later blog post (this one has already been overflowing its limitations). Jerome continued to work on his Bible translation in Bethlehem and Jerusalem, and after his death the work was completed by his disciples. The Vulgate then became the dominant Bible text of the Catholic Church until 1979.

The attempts to make Latin the language of the Catholic Church were just one of many initiatives by Damasus to direct the attention of the contemporary world away from the increasingly Greek-dominated eastern part of the Roman Empire. He also staged an extensive "advertising campaign" to attract pilgrims to Rome.

Christians had venerated their martyrs for a long time. Tertullian had in 197 written that the “blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Christians” in the sense that their sacrifices became proof to non-Christians that the Christian faith was so strong that its adherents were willing to die for it. Damasus, who was born in a place surrounded by Christian catacombs, had since his childhood witnessed how Christians wanted to be buried as close as possible to those who had died for their faith. It was as if Christians hoped that martyrs would be able to plead their case before God.

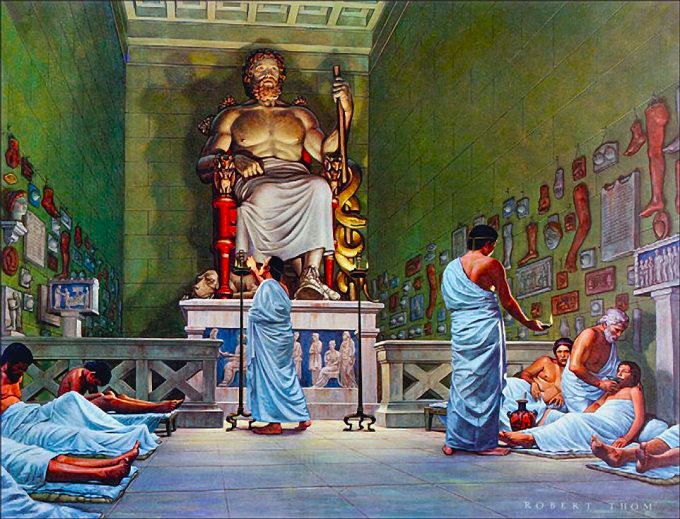

When Christianity became acceptable at the beginning of the fourth century, martyr worship increased, more and more people made pilgrimages to their graves, over which churches and chapels were built. It also became increasingly common to collect and venerate relics of holy men and women, the word comes from the Latin relinquere, to leave behind.

Scholars have sought a variety of reasons for this phenomenon. For example, as Christianity captured more and more believers, more and more began to feel threatened by the paganism they had left behind. The ancient gods were perceived as threatening demons and the growing, ever-imminent danger from approaching barbarians and violent sectarians meant that Christians sought refuge within their sacred areas, among rites and objects imbued with power. Another explanation is that the renovated martyrs’ tombs, and/or the churches and chapels that grew up in connection with them, were seen as equivalents to the temples that previously had been considered to bestow healing, for example those dedicated to Asclepius, the god of medicine.

Personally, I believe, especially considering that the cult of martyrs and relics was particularly widespread in Rome, that educated bishops like Damasus, who were well acquainted with Roman traditions, knew how to utilize the pagan concept of numen. A word often translated as “god”, but with the caveat that it is more of a “personified power” than a god in the usual sense of the word. A numen can be almost anything; a stone, a plant, or an animal – or even be part of a human being. If a human being possesses a numen, it might be defined as a force constituting their inner personality; their soul, charisma, virility – perhaps even their ability to do things in the best possible way. Each numen had a very specific, limited function. Concepts and beliefs that could easily be transferred to beliefs in a force linked to deceased martyrs, or objects and places that could be associated with them.

Before Damasus became bishop of Rome, the calligrapher Furius Dionysius Philocalus had compiled a Chronographia, a kind of illustrated calendar that included the birthdays of emperors, official feast, lists of Roman consuls, prefects and bishops, as well as brief accounts of the history of the city and its fourteen “regions”. The enterprise had been financed by a certain Valentinus, apparently a member of the powerful Symmachus family, but unlike its patriarch, Valentinius was clearly a Christian because the Chronographia contained an extensive list of the city's Christian martyrs.

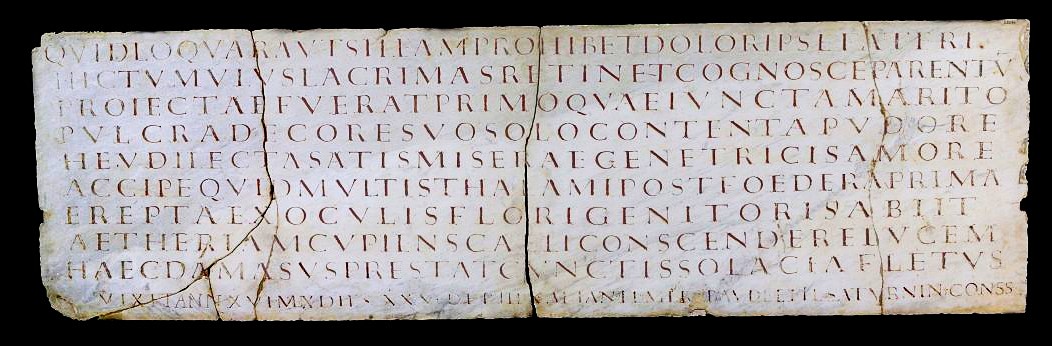

When Damasus in 366 had usurped absolute power as bishop of Rome, he contacted Philocalus and commissioned him to produce marble tablets to be placed in various places throughout Rome honouring the memory of the city’s martyrs. Damasus wrote the epitaphs himself. His intention was to create an Urbs sacra, a holy city, filled with allusions to the holy martyrs. The word “martyr” means “witness, presence” and indicates enduring protection. The multitude of holy places indicated by Damasus’ marble tablets became a means of attracting pilgrims. Thirty of these inscriptions have been preserved, in original, as fragments, or as copies, but there must have been considerably more.

Damasus' search for martyrs seems at times to have been somewhat inventive. Seventy-seven of the martyrs mentioned on the marble tablets are missing from Philocalus’ Chronographia and might well have been “discovered” by Damasus.

He did not focus solely on above-ground sanctuaries, where he set up his marble slabs, but also drew attention to the catacombs, making them more accessible to visitors by arranging stairs, guides and lighting, while taking bone remains from various places, gathering them in specific, accessible places, such as the famous “papal crypt” in the catacombs of San Callisto, the resting place for the remains of five Roman bishop martyrs.

Some of Damasus’ inscriptions pay tribute to several martyrs

If you should ask: here lie crowded together [congesta] a throng [turba] of saints. The tombs-to-be-venerated retained the bodies of the holy ones when the heavenly kingdom took up their sublime souls. Here are the comrades of Xystus who carried off trophies from the enemy; here a numbered bodyguard which serves the altars of Christ; here the one is placed who lived long as a priest in peace; here are the holy confessors whom Greece sent. And here the young boys and old men and the chaste grandchildren and the one who was pleased to retain her virginal chastity. I confess that I, Damasus, wished to lay my own bones here, but I was afraid to disturb such holy ashes of the saints.

Those of Damasus's epitaphs that celebrate female martyrs generally praise their "chastity, modesty, and fidelity," while men are praised for their dignity, eloquence, and often "old-fashioned" outlook on life. Damasus seems to have been an ambitious man and he himself appears in almost every epitaph he wrote. Some of them indicate that he discovered the resting places of some of martyrs whose memory he celebrates. For example, while remembering the martyrs Marcellinus and Peter Diocletian he reminisced

When I was a boy your executioner bore to me, Damasus, your tomb: he said that these commands were given to him by the mad butcher—that he should sever your necks then in the middle bushes, lest anyone be able to recognize your tomb. [He said] you, eager, to have prepared your tomb with your own hands, and after to have lain obscured under a cave. Afterwards [he said] Lucilla considered that it was more pleasing lay your limbs here, on account of your piety.

It even happened that Damasus seemed to have forgotten to pay tribute to the saint in question and only described his own efforts to assure its memory. As on a marble tablet in memory of the executed centurion Cornelius:

Damasus concerns with accessibility. Look: with the descent made and with the shadows fleeing you, see the monument of Cornelius and his sacred tomb. The zeal of Damasus accomplished this work (though he is ill) that there might be better access, and that the help of the saint be made convenient for the people, and so that you prevail to pour out prayers from a pure heart to make Damasus able to rise up better, though not love of the light, but care for his work, is what seizes him.

Shortly after Ammianus Marcellinus wrote about Damasus' struggle to obtain the episcopate, he mentions how the priests of Rome strove for power, wealth, and dignity.

Considering the ostentatious luxury of life in the city it is only natural that those who are ambitious of enjoying it should engage in the most strenuous competition to attain this goal. Once they have reached it, they are assured of rich gifts of ladies of quality; they can ride in carriages, dress splendidly, and outdo kings in the lavishness of their table. They might be truly happy if they pay no regard to the greatness of the city, which they make a cloak for their vices, and follow the example of some provincial bishops, whose extreme frugality in food and drink, simple attire, and downcast eyes demonstrate to the supreme god and his true worshippers the purty and modesty of their live.

Vanity – it may be forgiven that Damasus, like so many of us, was afflicted with that defect. His contribution was certainly in several areas crucial for the spread of Christianity throughout the world. So why not build churches in his honour, canonize him and pray to him so he might “grant us, O God, to follow the example of Pope St. Damasus, him whom we love and who revealed to us Your word”? Indubitably he was as it says above one of the entrance portals to his modern church Ego sum pastor pastor bonus, I am the good shepherd.

Or? Is Saint Damasus really worthy of his role as a saint, a pious role model and intercessor between his believers and God? This is actually quite doubtful, especially if one takes into account what his contemporaries had to say about him. Ammianus mentioned a certain Viventius as an exemplary prefect of Rome. He was

A former questor [juridical advisor] of the imperial palace, an upright and wise Pannonian [from what is nowadays more or less equivalent with Hungary and Slovenia], under whose quiet and peaceful administration there was general plenty. But he too had to endure an alarming outbreak of violence by the turbulent populace, which arose as follows. Damasus and Ursinus, whose passionate ambition to seize the episcopal throne passed all bound, were involved in the most bitter conflict of interest and the adherents of both did not stop short of wounds and death, Viventius unable to end or abate the strife was compelled by force majeure to withdraw to the suburbs. The efforts of the partisans secured the victory for Damasus. It is certain that in the basilica of Sicinius, where the Christians assemble for worship, 137 corpses were found on a single day, and it was only with difficulty that the long-continued fury of the people was later brought under control.

The Basilica of Saint Sicinius, which had previously been a large Roman court building, was located adjacent to the Forum. The basilica had been converted into a church on the advice of Damasus's predecessor on the episcopal throne – Liberius, who had been elected with the support of Rome's influential and wealthy widows, However, when several Christian groups opposed the election of Liverieus, he had to share the episcopal office with a certain Felix. This did not please the Christian majority of Rome, who, under the slogan "one God, one Christ, only one bishop!" forced the emperor to drive Liberius into exile. During Liberius’ absence the Christian congregation became divided in its support to Liberius or Felix. Damasus supported the latter and when the two bishops had died, a violent fight broke out over who would succeed them. Damasus, who was supported by the wealthy ladies, had repeatedly shifted his support between Liberius and Felix, but when the latter had managed to remain on the episcopal throne for eight years, Damasus eventually stood wholeheartedly by his side. Ursinus, however, remained Liberius’ man and was supported by the majority of Rome’s Christian citizens.

The Collectio Avellana, the Avellana Collection, which is preserved in the Vatican Library, contains 244 documents from the period between 367 and 553. It includes the correspondence between emperors and Roman bishops, as well as imperial decrees, and personal papers of several bishops. The Collectio Avellana was compiled sometime in the late 6th century. A document found among the Collectio Avellana relates

that when Damasus, who had always sought to be bishop, learned that Ursinus had been consecrated as bishop instead of him, he used bribes to rile up all the charioteers and ignorant rabble, and armed with weapons he broke into the Basilica of Julius, and a great slaughter of the faithful raged for three days. Seven days later, in the company of all the perjurers and gladiators whom he had corrupted by paying huge sums of money, he took possession of the Lateran Basilica and was there ordained bishop.

After getting rid of Ursinus, Damasus began to persecute the Romans who did not support him. They lived in fear and were subjected to all kinds of abuse and bloodshed. On one occasion, Damasus ordered the expulsion of seven oppositional priests, which caused a general uprising. A mob broke into the prison where the priests were awaiting their expulsion, freed them, and took them to the Basilica of Liberius. Once again, Damasus gathered

gladiators, charioteers, gravediggers, and all the clergy that supported him, and with hatchets, swords, and clubs they besieged the basilica, inciting a great battle […] They broke down the doors and set fire underneath, then rushed in and ransacked the building. Some members of Damasus’ household, while they were destroying the roof of the basilica, were killing the faithful congregation with the tiles. Then all of Damasus’ supporters dashed in and killed a hundred and sixty of the people inside, both men and women. They wounded many more, many of whom later died from their wounds. But no one from Damasus’ party was killed.

It is possibly this second attack on Ursinus's followers that Ammianus alluded to. During the aftermath of this massacre representatives of the outraged Roman population sent their complaints to the emperor, who resided in Milan. However, … Damasus had powerful patrons in Rome, especially among wealthy and respected Roman women who loved him so much that he was called “ear-picker of ladies”, According to his supporters, the epithet meant that Damasus cleared out the ears of the ladies from erratic teachings and eventually introduced the correct doctrine, while his opponents interpreted the phrase as meaning that he pricked the ladies’ with slander of his opponents.

The pleas of Damasus’ opponents for justice fell on the emperor’s deaf ears and Ursinus left the city on his own accord. However, Damasus's bloodthirstiness did not abide. Ursinus's faithful followers gathered in the catacombs, where they celebrated mass without their exiled priests. On one such occasion, when Ursinus’ followers had gathered by the tomb of St. Agnes, Damasus suddenly burst in with his armed mob and several of the worshippers were cut down in a "devastating bloodbath".

It is admittedly difficult to understand, after reading these contemporary condemnations, how such a bloodthirsty and vain bishop can be hailed as a saint and, moreover, as late as 1969, have a large Roman church built in his honour. Nevertheless, victors tend to erase unsightly stains from their legacy. It cannot be denied that several of Damasus’ efforts laid the foundation for much of the current papacy, with all its advantages and shortcomings.