ABOUT THE INCOMPREHENSIBLE: Why is nature beautiful?

Early morning, late October. The blue infinity of the sky is reflected in the lake's mirror. Not a ripple. The leafy forest glows in autumn colours. Each leaf with its own nuance in shades of golden yellow, dark red and rust brown. Silence, except for the rustling as I cross over a thick carpet of fallen leaves. Today, every detail has a spell of its own; a fallen tree covered with succulent moss, a lonely, dark green spruce surrounded by beech trees with canopies reflecting the sunlight. A walk around the lake, through the woods, across the meadows. An ancient oak is spreading its intense rust red crown above boulders in the meadow beyond the village. From distant pastures among thin veils of mist, fleecy bull calves are spreading their bellows over the neighbourhood.

The feeling of tranquillity and profound beauty that nature bestows upon us, how can it be explained? Appreciation of human beauty certainly finds its origin in the sexual instinct, in the same way as insects are attracted by the splendour of flowers. As the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1710-1778) wrote: "Flowers are the exposed love of plants." But why do we become enamoured in the beauty of nature? Which survival instinct does that feeling answer to?

Nature is an elusive mystery. Many have sought the source of the feeling of intense satisfaction that the sheer presence of nature occasionally may bring us, not the least Carl Linnaeus, this strange man who was a genius and a systematician bestowed with an enormous self-esteem and a childlike enthusiasm. In one of his five autobiographies he wrote about his childhood home:

Around this Stenbrohult of mine nature had created the most beautiful flower fields, there Carl grew strong with his mother´s milk amidst flowers that from the beginning gave him so much pleasure that no later distress could obliterate it. He who later commanded all the herbs in Flora´s army was here bred together with them.

In his search for God's invisible hand in nature Linnaeus named and systematized every plant and animal known by him and his disciples, who travelled the entire world, like a new Adam (who named everything to gain power over creation) Linnaeus binomial nomenclature, which meant that every living organism got a name for its genus (capitalized) and species (with small letters), sparked a scientific revolution through which a systematization of existence made it possible to control it.

This eighteenth-century endeavour to describe and categorize everything around us co-existed in Linnaeus alongside a childish joy of nature's beauty and wealth, expressed everywhere in his writings, perhaps most famously in his introduction to his Systemae Naturae:

I saw the infinite, all-knowing and all-powerful God from behind as he went away, and I grew dizzy. I followed his footsteps over nature's fields and saw everywhere an eternal wisdom and power, an inscrutable perfection.

Despite his deep knowledge and ingenious systematising of what he saw and experienced in nature Linnaeus could not avoid to recognize its ”inscrutable perfection". Even for a dedicated scientist like Carl Linnaeus was nature's innermost being concealed. As the son of a strict clergyman Linnaeus remained a convinced Christian all his life, without the slightest trace of doubt about God´s existence and almighty power. Linnaeus knew his Bible inside out. To see ”God from behind” was not a randomly chosen expression, it finds its origin in Exodus, where we are told that Moses during the Israelites' forty years of wandering through the wilderness brought with him a tent which he called the "Tent of Meeting".

Now Moses used to take a tent and pitch it outside the camp some distance away, calling it the “tent of meeting.” Anyone inquiring of the Lord would go to the tent of meeting outside the camp. And whenever Moses went out to the tent, all the people rose and stood at the entrances to their tents, watching Moses until he entered the tent.

This tent reminds me of a strange encounter I once had in southern Brazil, where I visited a Guaraní camp. Most Guaranís, as Mose´s Israelites once were, are a wandering and searching people. My meeting with them was both surprising and somewhat shocking. They did not live up to my expectations of being noble savages surrounded by purpose-built, tasteful huts and men and women attired with multi-coloured feathers, contour-cut hairstyles, stylish tattoos and patterned loincloths. Instead, the camp was an assortment of miserable huts, not much more than heaps of twigs, inadequately covered with dirty plastic sheeting in various colours. Everywhere there were rubbish strewn around amidst naked children and skinny dogs were playing. The camp's inhabitants were dressed in rags, but friendly and most of them spoke both Guaraní and Spanish. They introduced me to their paje, shaman, a wrinkled old man wearing a pair of frayed denim shorts sitting on a tree stump and splitting logs with a long knife. The shaman looked up at us and squinted:

- He speaks just as good Spanish as I do, explained the young man who had welcomed me to the camp when I arrived in a jeep.

- Ask him about whatever you want to know. He has all the answers.

I asked the shaman if the camp had a shrine. Laughingly he pointed the knife towards a hut behind him. It was oblong and larger than the miserable plastic-covered huts that surrounded it. However, even the sanctuary was covered with ugly plastic sheeting placed over twigs and poles.

- What's in there?

- God, said the shaman and showed his bad teeth in a broad smile.

- There and everywhere, he added.

- But why do you have a shrine if God is everywhere?

- We must have a place where we can meet him. You have that as well. You have your churches. Right?

- Can I visit your shrine?

The old man laughed and waved playfully with the knife.

- No, no, no white man has ever been there. It is not for you. You do not understand.

It is said that God was inside Moses´ tent as well and that Moses was the only one who was allowed to enter. Inside the tent, God spoke to Moses "face to face, as one man speaks to another." But, since Moses could not see God, he was somewhat doubtful if he really could trust him. Therefore, he prayed to God that he would allow him to catch a glimpse of him in all his ”glory”. God replied:

“I will do the very thing you have asked, because I am pleased with you and I know you by name.” Then Moses said, “Now show me your glory.” And the Lord said, “I will cause all my goodness to pass in front of you, and I will proclaim my name, the Lord, in your presence. I will have mercy on whom I will have mercy, and I will have compassion on whom I will have compassion. But,” he said, “you cannot see my face, for no one may see me and live.” Then the Lord said, “There is a place near me where you may stand on a rock. When my glory passes by, I will put you in a cleft in the rock and cover you with my hand until I have passed by. Then I will remove my hand and you will see my back; but my face must not be seen.”

God and his creation are related. God exists in nature, but as its innermost mystery. You can imagine him, but it is not the same as seeing him. God's infinity cannot be framed by our limited conciousness and inadequate language. As Paulus wrote in his first letter to Timothy:

God, the blessed and only Ruler, the King of kings and Lord of lords, who alone is immortal and who lives in unapproachable light, whom no one has seen or can see. To him be honour and might forever.

But in the nature we may perceive God's presence, in any case many of the Romantics assumed that it would be possible, among them the Swedish hymn writer Johan Olof Wallin (here in my clumsy translation):

Where is the friend for whom I'm yearning?

When day breaks, my longing keeps on burning.

When the day flees, I have not found Him yet,

my heart´s desire is never met.

I perceive His tracks and mighty power wherever

a flower smells, where the wind stirs forever.

With every breath I take

His love remains awake.

I hear His voice, where the summer breeze is rustling,

where the river sings and roars; where bees are bustling.

His comfort fills my heart,

though we remain apart.

Alas, there is so much beauty in every vein

of creation, of life itself. Could all this be in vain?

No, how beautiful is the very source of being,

that I wish and hope to finally be seeing.

We are all undeniably an integral part of nature and by searching within ourselves and try to understand our perceptions of beauty, it is maybe possible to understand why we perceive nature as beautiful. But what is this beauty? What does it tell us? Jan Olof Wallin seems to combine the beauty of nature with God's compassion and goodness. Just as in a hymn that I as a kid learned in school, at a time when catechism was still part of a moralistic curriculum of the Swedish school.

Morning comes with golden beams

hear how every river and all the streams

the wind and birds in every wood

murmur and sing: God is good, God is good!

Nevertheless, the other case could also be made, like in a nasty song written by Eric Idle and performed by the Monthy Python team:

All things sick and cancerous

All evil great and small,

All things foul and dangerous

The Lord God made them all.

Each nasty little hornet,

Each beastly little squid

Who made the spiky urchin?

Who made the sharks? He did.

All things scabbed and ulcerous

All pox both great and small

Putrid, foul and gangrenous

The Lord made them all.

Is nature really good and well meaning? Or are aesthetic experiences beyond good and evil? When we talk about beauty, we might accept as the Danish director Lars von Trier said after each installment of his absurd TV horror thriller Riget:

... If you are fascinated by The Kingdom and once again wish to spend some time with us, then be prepared to take the good with the bad.

Nature is namely not good, often it is in fact quite often the opposite of good - it can be ruthless and extremely cruel. Charles Darwin was an agnostic and thus quite different from Linnaeus, who according to him "was so remarkable for his sagacity ". Darwin wrote in a letter to his devout American colleague Asa Gray, who considered Darwin's discoveries to be proof of the existence of God, that He created the universe in accordance with a logical design:

I own that I cannot see as plainly as others do, and as I should wish to do, evidence of design and beneficence on all sides of us. There seems to me too much misery in the world. I cannot persuade myself that a beneficent and omnipotent God would have designedly created the Ichneumonidae with the express intention of their feeding within the living bodies of Caterpillars, or that a cat should play with mice.

In an essay, Bourgeois and Radical Conceptions of Nature in Swedish Literature of the 1930s the exceptionally sharp and witty literary critic Stig Ahlgren attacked the swagger and inability of nature lyricists who tried to convey their aesthetic sensibility and closeness to nature by naming each tree, flower and mushroom they came across. Ahlgren described how sensuous depictions of nature could be perceived as an "ideological battleground" where conservative writers moralized nature and offered scenic beauty as a surrogate for social justice and on top of that dreamed of nature's vengeance on the callous chaos of modern civilization.

In a review of the poet Sten Selander's collection of poems Sommarnatten, The Summer Night, Ahlgren pitilessly tears his favourite victim to pieces, characterizing the bourgeois lyricist as a humourless and utterly dishonest character, whose amateurism and borrowed feathers "are so extremely well camouflaged that they do not disturb the average reader". According to Ahlgren could Sommarnatten:

be considered as an attempt to vary the magical fantasies of the Shakespearean Puck in A Midsummer Night's Dream by instilling them with a Swedish national flavour, a Nordic pagan character. Nevertheless, if the poems are placed alongside Shakespeare´s lyricism Selander´s effort seems to have been inspired by Jägerskiöld-Kolthoff´s Encyclopaedia of Nordic birds. There is no lack of sandpipers, siskins, nightjars, robins and cuckoos, a magnificent and encyclopaedic bird life that would have made the poet from Stratford on Avon green with envy.

Sten Selander was undeniably hostile to modernity and despite the scientific attitude in a lot of his writings he may be considered as an anachronistic romantic who wanted to restore a bygone agricultural Sweden, as it looked before the entry of machines . Nevertheless, Selander's attempt to turn the clock back made him a forerunner in the fight against pollution, an attempt to counter an escalating exploitation of nature and a senseless destruction of its beauty. A misery depicted by the novelist Kerstin Ekman's in her Herrarna i skogen, The Gentlemen in the Forest, a scathing indictment of the exploraters that currently are destroying the biodiversity and beauty of Swedish forests:

I was on my way to go fishing in the lake. The day was hot and to shorten my walk I tried to make my way across a large clear cut. I had not realized how difficult it would be to move around among the debris left behind by the forest machinery. Sweating and tired, I came across a deep furrow in the ground. There, a clear brook had once murmured, but now the ditch was dry. The rocky and sandy bottom was completely desiccated. I saw some dented metal cans down there. The drivers had changed the oil in their machines. The only moisture left by the heat was some pools of hazy oil, glistening in the colour spectrum, unpalatable in the torridness.

The sad feeling of irredeemable loss that overtakes you when a beloved landscape has been massacred by huge forestry machinery is hard tackle. The tangled devastation breaths death and definite, nasty change. So much life and joy gone to waste.

For most of us, memories of beauty and freedom are linked to nature. In his mainly autobiographical novel Flowering Nettle the Swedish Nobel laureate Harry Martinson describes is first memory. He is three years old:

The sisters cry out to him not to run away. But he is chasing a yellow butterfly, fluttering without rest. It takes off like a leaf that singles down from an autumn tree. It does not want to be devoured by the eagle stomach of the straw hat. It wants to escape from the animal that is a child, who for a butterfly is a great horror. The child is the butterfly´s tiger and crocodile and so the hunt goes on.

Martinson is one of those authors who effortless and admirably has been able to capture nature’s beauty and mystery. He once wrote that descriptions of nature may serve as a realm "where the precise and visionary approach one another, agreeing or disagreeing, and battles". He is able to write about the the cosmic immensity of a sunlit meadow, how the ”smallest territory, the landscape of the tussock by your shoe, is entitled to the same respect and has as much to say as the great and wide valley.”

In his writing Martinson succeeded, as the Swedish Academy so aptly wrote in its justification for his disputed Nobel Prize, ” to catch the dewdrop and reflect the cosmos." Nevertheless, like other great writers who are familiar with nature and its immense beauty Martinson knew that such a feeling cannot be accurately depicted, only experienced. The only thing the written words can do is to suggest what it means to be bedazzled by nature. As when he is describing the dragonflies:

Their eyes, thorax, and wings, indeed their entire being are subtle lines in a refined poem, so delicate that they would be crushed if described. Their poem can only be read directly where they live, within a passing moment.

Despite the impossibility to identify, understand and explain nature´s beauty, people have for thousands of years tried to find the key to its harmony and beauty - alchemists, astrologers, philosophers, mathematicians and nuclear physicists. Love and beauty remains an eternal mystery, like in the song of Leonard Cohen:

All the rocket ships are climbing through the sky

The holy books are open wide

The doctors working day and night

But they'll never ever find that cure,

That cure for love.

Some scientists, philosophers and mathematicians have found rules, patterns and systems that indicate contexts that might explain concepts like harmony and beauty.

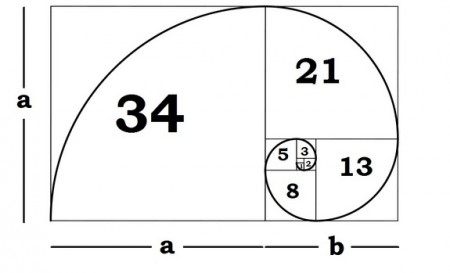

The most famous attempt to subject beauty to a regulatory framework is probably what has been called the Golden Section, or φ (f), i.e., the relationship which occurs by dividing a line in a longer section which you may call a and a section half as long as a, called b, then the section a + b relates to a in the same way as a relates to b.

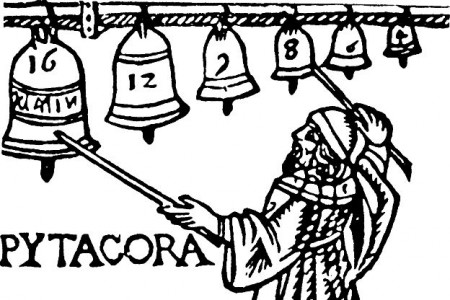

Already Pythagoras (590-495 f. Kr.) knew about this relationship and began experimenting by strumming a string which he divided in various ways. Finally, he concluded that if a string of a certain length gave a certain tone, a so-called keynote, was divided in two it produced an octave (the eighth and highest tone of a major scale). But that was not all. If a string producing a keynote was divided at two-thirds of its length a quint was heard (the fifth tone of a major scale). By snapping his string Pythagorean found a system of twelve tones, which now forms the foundation for music's harmonic structure.

Pythagoras thought after finding accurately sounding harmonies and combining them with the Golden Ratio, he had discovered the final solution to the mystery of nature's essence and beauty. Sound and math reflected it and they are always with us. Nature’s beauty could not only be seen, it could also be heard, but we are so used to hearing it that we no longer consciously can discern it. He called it the Music of the Spheres. Pythagoras believed that God was a mathematician who had ordered the universe according to strict rules and mathematical harmony which for him was identical with beauty.

Pythagoras is among the first philosophers who managed to express a phenomenon - the pure tones - through a succession of numbers. His insights made him believe that he could prove that everything can be quantified and explained through mathematical formulae and he founded a religion based on that belief. As so often is the case with such initiatives, Pythagorean religion was a mixture of wisdom, oppression of other opinions and sheer silliness.

The Golden Section was soon applied to investigations of the human body. Philo of Alexandria, a contemporary of Jesus, tried to unite Greek and Jewish philosophy and since many of the Christian Founding Fathers also had their residence in the cosmopolitan Alexandria it is likely that such Jewish-Greek speculations affected their beliefs. Philo wrote about Adam Kadmon, the original man, a creature that was God's absolute image, a prototype that He had made use of while creating the universe.

Adam Kadmon was often equalled to the Logos of God. Logos is a concept usually translated as "word", but its significance is actually closer to the meaning that the Greek philosopher Heraclitus gave it, namely "Universe's inherent order." Adam Kadmon is neither man nor woman, but an idea, in the sense of εἶδος, eidos, - pattern, shape or structure, a kind of thought model which God turned into material creation. As Adam Kadmon looked like God, s/he must be perfect and since humans are images of Adam Kadmon, God´s Logos in material shape, human dimensions could also be perfect, their interrelation could thus probably serve as an image of perfect harmony and become a clue to how the entire Cosmos is constructed.

Philosophers and mathematicians soon realized that the Golden Ratio probably was the formula that best demonstrated the relationship between all parts of the human body. The Franciscan monk Luca Pacioli published in Venice, in 1509, a book about the Golden Ratio which he called De Divina Proportione, About Divine Proportions.One of its chapters deals with the Antique Roman architect Vitruvius (70 f.Kr - 15 e.Kr) who stated that architecture should imitate nature and to establish the best proportions of a building, or an entire city, every architect should examine the proportions of nature's greatest works of art – the human body. Or as a fragment of the Greek philosopher Protagoras (481-420 BC) somewhat cryptically states: "Man is the measure of all things: it is the dimension of the present and if not not present, it is not."

One person who before Luca Pacioli had nurtured similar ideas was the mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci (1170 - 1250) who after studying the growth of rabbits came to the conclusion that what has become known as the Fibonacci Sequence best explained how rabbits´ reproduction functioned. In a Fibonacci Sequence each number is the sum of two previous numbers, i.e. 0, 0 + 1 = 1, 1 + 2 = 3, 3 + 2 = 5, 5 + 3 = 8, 8 + 5 = 13, 13 + 8 = 21, etc. in an endless row.

The strange thing is that Fibonacci frequencies show up everywhere in nature; how leaves arrange themselves in a plant, or the scales in a pine cone. It actually appears as if Fibonacci´s model can be applied to most organic things - a cell, a grain of wheat, a bee hive. Of course, it is probably not any conscious adaptation to a given pattern - leaves are arranged in such a particular manner to maximize the space available for each of them and their internal relations also have to be ordered in such a way to allow each leave to receive as much light as possible.

The reason to why all these arrangements finally have turned out to be as effective as they are now, and can be described through mathematical formulas, is probably the result of millions of years of adaptation to different environments. A process of trial and error that has not been governed by any preconceived plan. Nevertheless, some doubts remain, especially since string theorists now have begun to assert that the entire universe is constructed according to more or less identical patterns.

I'm far from being a mathematician and the best thing I should do is to follow Wittgenstein's advice: "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent." Therefore I will not go into how the Hungarian biologist Aristid Lendenmayer and the French-American mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot have demonstrated how mathematically, computer constructed fractals can reproduce growth patterns of various plants and how fractal like patterns are found in nature; in areas as diverse as cloud formations, river movements, shapes of mountains, coastlines, snowflakes, crystals, blood vessel branching and ocean waves.

It's easy to get the feeling that all this research and inquiry about nature would make it more understandable, but it is not actually so. Nature's mystery and beauty continues to baffle us and do not seem to be affected by explanations and ingenious descriptions. Nature continues to live a life its own. Can beauty really be explained? It may simply be as the evolutionist Richard Dawkins states:

… brains were naturally selected to increase in capacity and power for utilitarian reasons, until those higher faculties of intellect and spirit emerged as a by-product, and blossomed in the cultural environment provided by group living and language.

The splendid Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, “Encyclopaedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts” was issued in 28 volumes between 1751 and 1772. Its chief editor, Denis Diderot, stated that the aim of the Encyclopedia´s publishers was to "change men's common way of thinking." It was an attempt to describe life without religious blinders and restrictions, among the entries there would be no dreaming, no unfounded speculation. However, problems soon arose. As my professor in art history, Aron Borelius, stated during one of his lectures:

In the spirit of Enlightenment, the Encyclopaedists assumed that they were compiling volumes exclusively based on reality. They wanted an encyclopaedia that could explain almost everything that had to be explained. Probably some of them considered that other books, other than those that were intended for simple entertainment, were really not needed. Perhaps they could accept one or two additions to their Encyclopaedia, to keep up pace with developments. But then they did the mistake of inviting Jean Jacques Rousseau to write about music, and the mighty structure collapsed like a house of cards.

Music, like mathematics, is an exclusively human activity, a kind of parallel world to nature, seeking its origin in the human brain. It is structure and design, with an inherent possibility to create infinite variations. Music may perhaps find its origins in nature, but it is completely artificial, built upon rock-hard logic - a false note, and an entire piece of harmonious music may be totally destroyed, as when an incorrect number prevents the proper result of a calculation. Yet music is mysterious and elusive, similar to the experience of a morning walk around the lake, you are momentarily immersed in it and when the event is now more, the memory lingers and does not have be explained

Rousseau knew that the world of reality is limited, but the world of imagination is boundless. Prior to a description of the sense of beauty and joy that nature bestows upon us, he halted his volubility and declared je ne sais quoi “I do not know what”.

Rousseau was far from being the first author to use that particular expression when he wanted to describe love and beauty, using it to indicate that the immensity of beauty cannot be described by words. To experience beauty is a highly personal sensation, born in the depths of a spectator's soul. Already in 1671, the French writer Dominique Bohours had complained about the disturbing routine of Italian poets to use the flaccid expression of Non so che! “I do not know what” just after they verbosely had described an incident or a feeling that ought to have culminated in a flamboyant depiction of love and beauty, exactly what every expectant reader wanted to hear instead of a disconcerting Non so che!

Apparently, Bohours was not entirely wrong and even long before he made his remark Italian authors had, with reference to the great Torquato Tasso (1544-1595), one of the Romantics´ great idols, insisted that their use of the phrase had nothing to do with ignorance, or lack of skill, but was an expression suggesting the great respect they had for the deep emotion that beauty awakened in their souls; a feeling of reverence not worthy of being sullied by inadequate words, it could only be experienced.

Rousseau used the expression je ne sais quoi during his comprehensive attacks on what he considered to be the artificial, pompous and parodic methods of description, which insensitive, contemporary poets used while appreciating what they called “classic” beauty. It was high time to restore respect for nature's boundless mystery, to free oneself and others from the prison of reason created by a degeneration of original purity and return to the high esteem of nature and spontaneity that characterized the open minds of noble savages.

Nature might appear as obscure, formless and enigmatic, but it can also be considered as powerful, free and strong, impossible to capture through precise and clear descriptions, or scientific systematizations. It excites us with grand and sublime scenery, or through meticulous detail of leaves and tiny insects.

I am attracted by unpretentious descriptions of the ever shifting nature, like those of the, Swedish author and water-colourist Gunnar Brusewitz, who wrote his books in a lakeside cottage with a view to the four quarters, sketching the shifting landscape, the birds and other animals passing by, unobtrusively describing his thoughts and impressions, interleaved with historical anecdotes and excursions into the past.

Though reading about nature is easily outstripped by rowing the boat across the lake, or a walk in the woods. Today I did neither the one, nor the other, after finishing writing this essay I drove my mother, my youngest daughter and her boyfriend to the old vicarage in Råshult. The house where Carl Linnaeus was born had to his great sorrow been burned down in 1730. Something that did not prevent him from recurrently return to Råshult, both in mind and reality.

We were alone there. The overcast and gloomy day gave the site an abandoned impression and took the shine from the autumn leaves. Beside the cottage, which had been rebuilt just after the fire, was a farm. A useless tractor, a rusted hydraulic crane and a pile of junk covered by white plastic sheeting wrecked the historical illusion. Nevertheless, beyond Linnaeus´ parents’ home were meadows with grazing bull calves, shining white in the dusk.

We walked over hillocks, through pastures with hazel bushes and old oak trees. The moisture smelled autumn fresh. Carl Linnaeus had spent his childhood and early youth among the same hills and pastures and it was during his walks down to the nearby lake that he had grown dizzy at the sight of the overwhelming grandeur of God's beautiful nature. The trees were no longer the same as three hundred years ago, though there was no barbed wire, asphalt or other traces of modern times, all was quiet and still. Time was nothing, the landscape did not need to be measured and interpreted. There was nothing I needed to do, no cutting, weeding and clearing, only breathing and watching, surrounded by nature's timeless tranquillity.

Blunt, Wilfrid (2001) Linneaus, the Complete Naturalist. Princeton N.J.: Princeton University Press. Borgen, Peder (1997) Philo of Alexandria: An Exegete for His Time, Leiden: Brill. Dawkins, Richard (2010) The Greatest Show on Earth: The Evidence for Evolution. London: Black Swan. Desmond, Adrian (1991). Darwin: The Life of a Tormented Evolutionist. London: W. W. Norton & Company. Eco, Umberto (2005) On Beauty: A History of a Western Idea. London: Secker and Warburg. Farrington, Benjamin (2000) Greek Science: It´s Meaning to Us. Nottingham: Spokesman Books. Gleick, James (1993) Chaos: Making a New Science. London: Abacus. Martinson, Harry (1936) Flowering Nettle. London: Cresset.