EVERYDAY GRAPHICS AND THE DARK SIDE

Lately I have had unusually vivid dreams, perhaps stimulated by my enthusiastic blog writing. Writing those might, like dreams, be likened to stepping into a strange, yet familiar world where I spend time with people I've met and books I've read.

Last night, as so often before, I dreamed about dead and living friends and family members. I had interesting conversations with them, within surroundings familiar to me, though nevertheless strangely changed, both indoors and outdoors. Action took place within memories of childhood regions, but mixed with landscapes I have later spent time within. My dreams often occur in and around slightly dilapidated houses, or even labyrinthine castles and mansions, which for some incomprehensible reason I am the owner of, or otherwise associated with.

Last night I drove with some friends and acquaintances through such landscapes and when we reached our final destination we walked through am unkempt parkland around my parents' long-forgotten cottage, which was not at all surrounded by a park, but a forest.

Now that I have woken up, I remember quite well what we were talking about, and also the titles and content of a couple of thick and smelly books I found on the veranda of a dingy and miserably dilapidated outhouse. I can't understand why I had left such interesting books out there and neither when nor where I had purchased them.

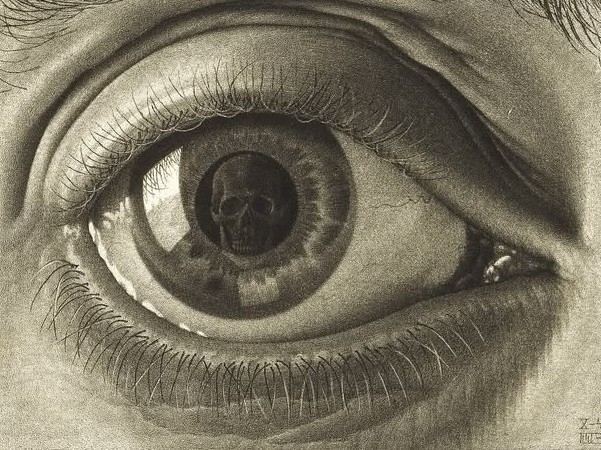

It was also strange that the walls inside that leaky and unusually large outbuilding were covered with wallpaper, which had peeled in large chunks and strips. Under them, as had been common in the past, the walls had been covered, not with pasted newspaper as they did then, but with engravings I recognized, by Goya, Klinger, Esher, and others.

The books and graphics of my dreams were perhaps connected to my latest blog posts and this made me think of my youngest daughter, who lately in anticipation of something better, is working in an acquaintance's newsstand. She told me that most of the regular customers are older people who buy newspapers and crossword magazines. The latter is perhaps partly due to the fact that older people, in fear of an increasing senility, have listened to the fact that brain activity is stimulated by crossword puzzles. Personally, imagine that my blog writing might have a similar beneficial effect on my aging brain. I really don't know.

That the engravings appeared in the world of my dreams was not so strange because I recently with my wife visited an art gallery here in Prague where we stay my oldest daughter. Now that I have woken up and the others are still asleep, I got the idea to use my blog to present some engravings that have remained in my memory.

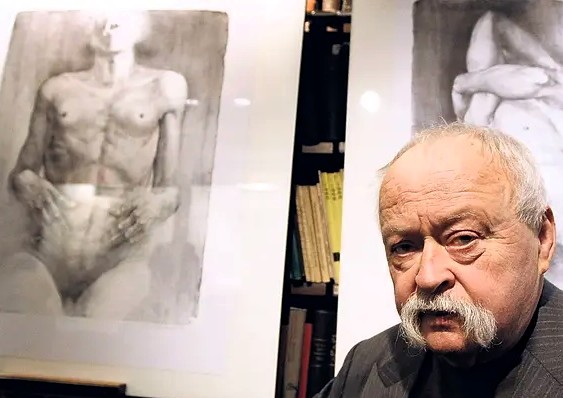

What Rose and saw here in Prague were works by Oldřich Kulhánek (1940 – 2013), a graphic artist who, among other things has made the Czech banknotes. It is one of my pleasures to scrutinize in countries I have ended up in and figure out what personalities they might depict. Banknotes are usually small works of art, and thus, are euro banknotes a disaster – boring as they are with their bland architectural motifs.

Kulhánek's Czech banknotes are works of art in their own right. Among other things, he produced the 500 corona banknote with an image of Božena Němcová (1820–1862) and of course I found out who this for ne earlier unknown lady might be.

Božena Němcová was married to a Czech patriot who, through his newspaper articles fought the Austro-Hungarian central power. However, he was a nasty domestic tyrant who tormented his wife and their four children. Finally, Božena left him and died in poverty.

Despite her marital suffering and other troubles, Božena had been a prolific and appreciated writer who had her patriotic articles both openly and clandestinely published. Her novel Babička, Grandmother, was based on her upbringing in the village of Ratibořice and is still popular among the Czechs. Perhaps out of a guilty conscience for allowing Božena to die alone and poor, the Czech patriots arranged a grand funeral and later erected several statues and monuments in her honour

Kulhánek also devoted himself to produce a number of parodies of various banknotes. Below, for example, he has manipulated a German hundred-mark banknote with a picture of Clara Schumann, married to the brilliant composer but later incurable madman Robert Schumann and herself a skilled pianist and composer. Incidentally, I consider the original to be an unusually beautiful banknote.

In his mock version of an older German banknote Kulhánek makes Karl Marx breaking into Clara's banknote to steal her earring.

Possibly in protest against the Russian-Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Kulhánek did a few years later make a ruble bank note depicting a fat pig.

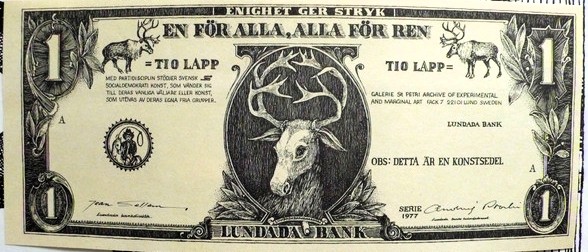

To present banknotes as a form of satire was also once done by my friend Jean Sellem in Lund, where he as a representative of the anarchist art movement Fluxus was the proprietor of the art gallery Skt. Petri. In 1977, when Sellem got into trouble with a municipal councillor named Rehn, who apparently wanted to withdraw the cultural support for his very interesting and lively gallery, he contacted the recently immigrated graphic artist Andrzej Ploski from Poland and together they created and distributed a number of "Ren noes”. Ren is the Swedish word for reindeer.

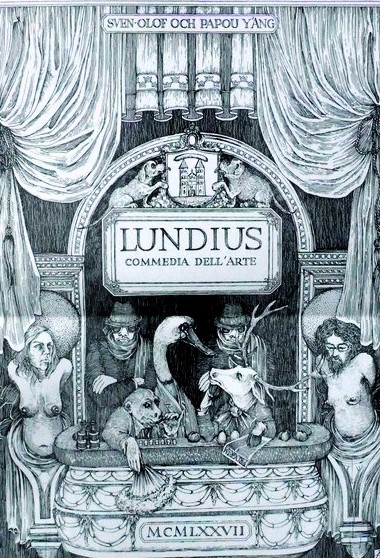

Sellem also asked me if he could use my family name to, together with Ploski, publish a satirical and partly incomprehensible little book which they called Lundius Commedia Dell'Arte

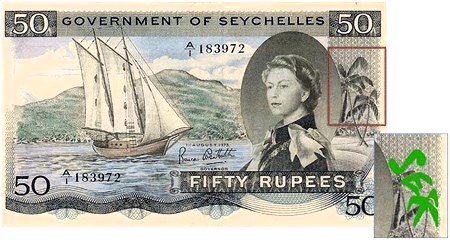

Even real banknotes have at some point been found to contain hidden satirical, or joking, allusions. Famous are banknotes from the small archipelago of the Seychelles, located far out in the Indian Ocean, printed in 1968. It was soon discovered that the pattern of the palm crowns on one of them could be read as "sex", while the pattern of corals on another banknote could be read as scum.

A debate ensued if the banknote's designers, Bradbury & Wilkinson, knew about the “joke”. The firm claimed it was an unintentional printing anomaly, but it seems that the whole thing was a prank by the engraver Brian Fox.

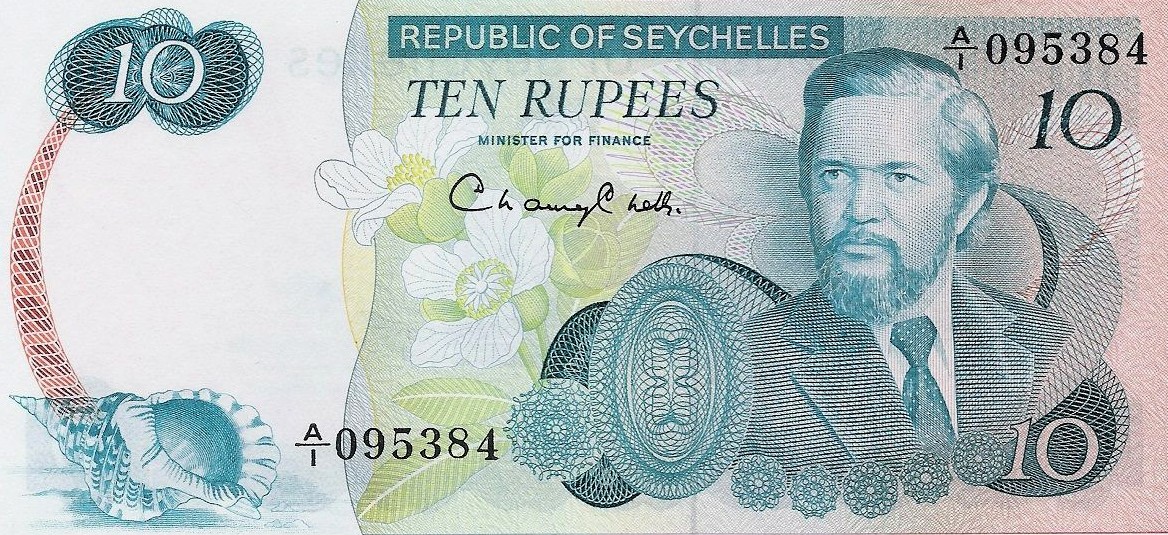

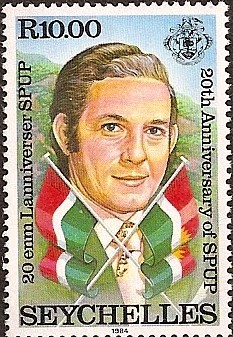

The Seychelles' British colonial administration allowed the banknotes to circulate for another eight years, until the islands in 1976 became an independent republic. Sir James Mancham, who previously had been the British governor now became president and adorned the Republic's new banknotes.

Nevertheless, they disappeared after just one year. When Sir Mancham haf travelled to England to celebrate Queen Elizabeth II's silver jubilee, his Prime Minister, France-Albert René, did with the help of about a hundred supporters and mercenaries, shipped in from Tanzania, carry out a military coup, thus beginning a twenty-year dictatorship. However, the new banknotes were not emblazoned with France-Albert René, but the stamps were.

.jpg)

Kulhánek also created several Czech stamps, such as the ones below that paid tribute to the somewhat unconventional Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, who to his court in Prague invited artists, musicians and not least alchemists such as the Englishman John Dee and astronomers such as the Dane Tyge (Tycho) Brahe and the German Johannes Kepler.

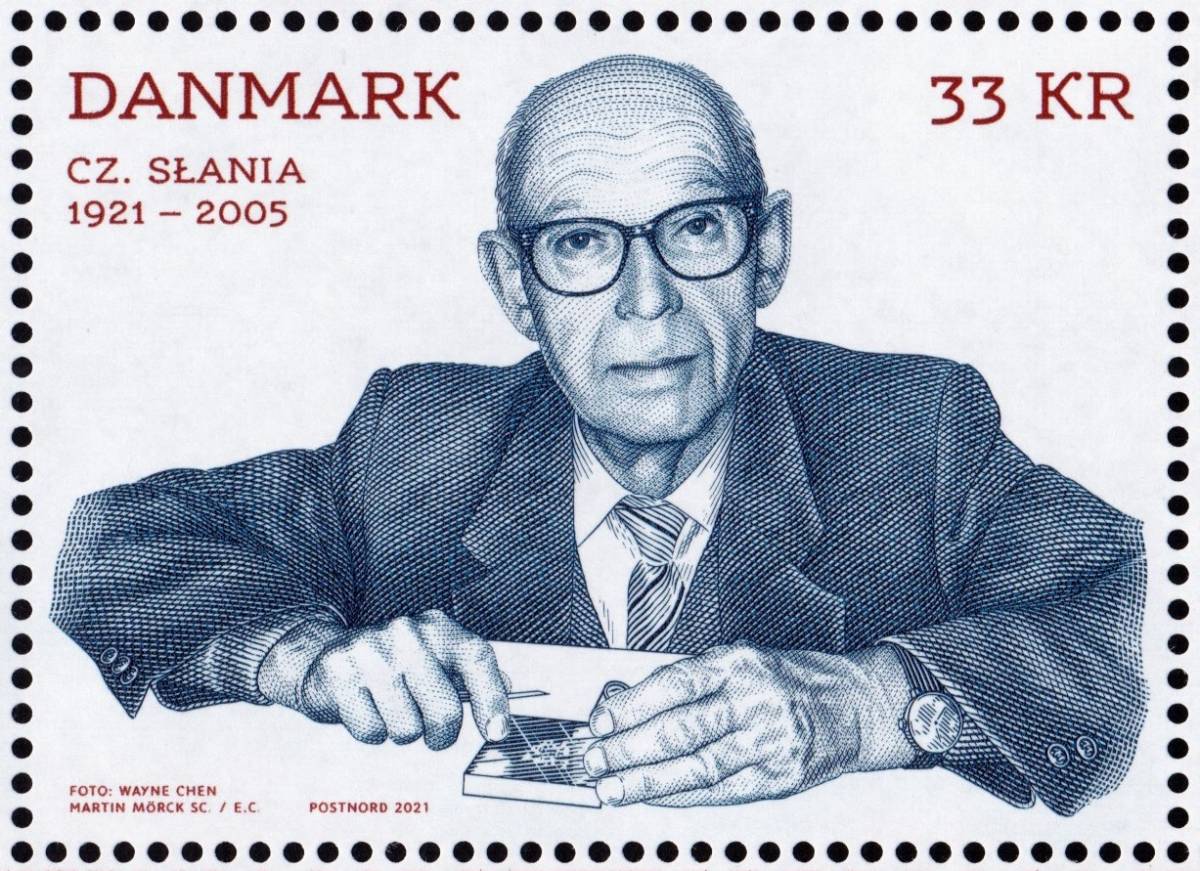

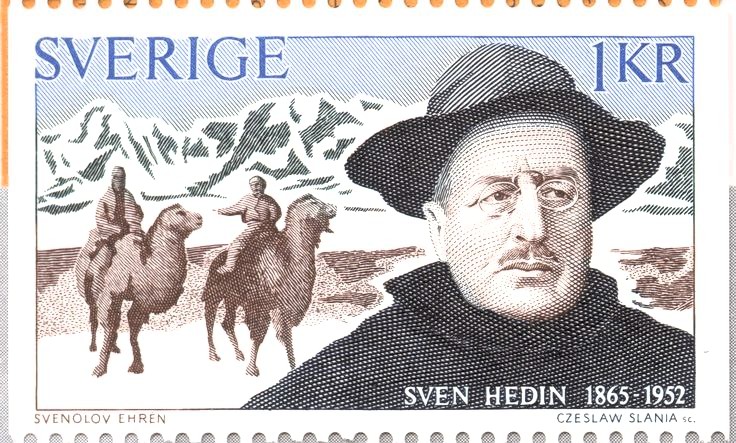

Like banknotes, stamps can also be regarded as small works of art and it is a shame that they are now increasingly disappearing and if they possibly remain, they have been replaced by boring multi-colour prints, far removed from the exquisitely engraved masterpieces they once were, produced by artists such as Kulhánek, and not least the more prominent Swede Czesław Słania (1921 – 2005). Słania came to Sweden from Poland in 1956 and up until his death he created more than 1000 postage stamps. At the time of his death, the Danish Post Office even issued a postage stamp in his honour, which was adorned with one of Słania's self-portraits.

Already as a young student in Lublin, Słania had forged German banknotes and official documents for the Polish resistance movement, and when he came to Sweden he was employed by the Swedish Post Office. In addition to the stamps he created for the Post Office, he also engraved postage stamps for no less than thirty other countries. Like Kulhánek, Słania also engraved banknotes, for example Lithuanian banknotes with Lithuanian luminaries like Beniuševičiūtė-Žymantienė (1845–1921), who under the pseudonym Žemaitė wrote a number of novels and short stories mainly set among the Lithuanian peasantry.

Žemaitė is reminiscent of the Swedish author and national hero Selma Lagerlöf and like her she was the daughter of landowners who had lost their properties and wealth. Both later became exalted and respected personalities in their respective homelands.

Selma Lagerlöf was portrayed on a Swedish banknote, though not engraved by Słania but by two young women – Toni Hanzon Kurrasch and Agnes Miski Török.

The new Swedish banknotes introduced in 2016 were provided with images by the graphic artist Göran Östlund and like the old ones also portrayed Swedish cultural personalities, but in my opinion they are not as aesthetically successful as previous banknotes. Take as an example the banknote with the once famous famous Swedish movie star Greta Garbo, I think it presents a messier impression, the portrait resemblance is poorer and the engraving is not so detailed.

Compare this banknote with Słania's masterful postage stamp of Greta Garbo as she appeared in the movie The Saga of Gösta Berling from 1924.

I am not a stamp collector, but I do have some Słania stamps which I received from my father and it is certainly a rewarding experience to examine them in detail. For example, Słania’s skilful rendition of the varied summer greenery around a steamboat on the Göta Canal.

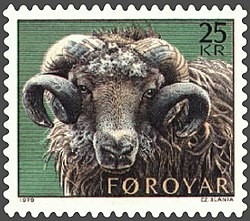

Słania's craftsmanship is also evident in his depiction of a Faroese sheep.

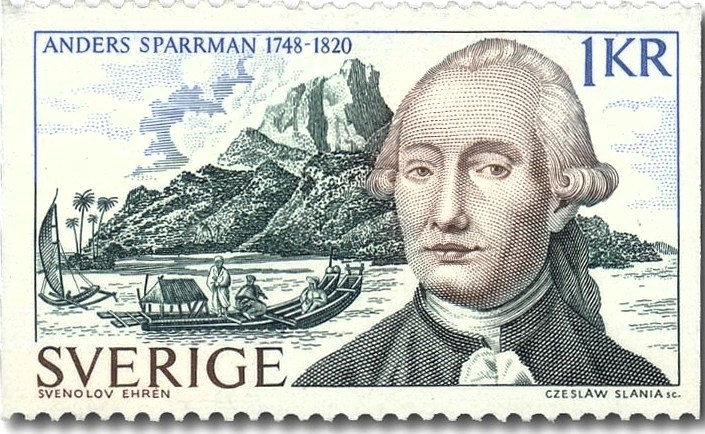

I also have a series of stamps in memory of Swedish explorers. Skilfully portrayed with exciting backgrounds, among them the famous botanist Linnaeus’ disciples such as Carl Peter Thunberg, who botanized in Japan, Indonesia and South Africa, and Anders Sparrman, who sailed with James Cook

and later scientifically minded adventurers such as Adolf Erik Nordenskjöld who made his way through the Northeast Passage and Sven Hedin who explored Central Asia.

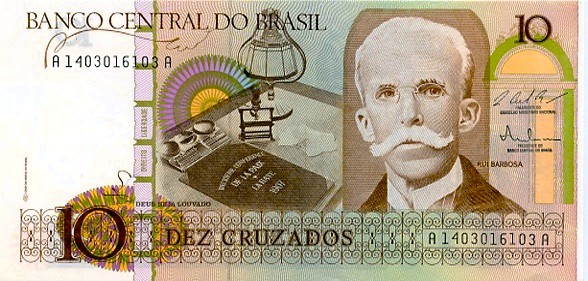

I also have a banknote from Brazil that turned out to be created by Czesław Słania and as usual I found out who Ruy Barbosa de Oliveira (1849 – 1923) could have been be.

It turned out that he had been a liberal-minded writer, politician and reformer. Barbosa had been influential in abolishing Brazilian slavery, something that did not happen until 1888. When the so-called Golden Law came into force, Barbosa made sure that all documentation of slavery and its Brazilian history was effectively destroyed under the pretext that he wanted to erase this stain from Brazil's history. In fact, it seems that Barbosa wanted to protect former, brutal slave owners from the consequences of their behaviour.

Considering how postage stamps and banknotes created by skilled graphic artists are disappearing, it is tragic to realize that yet another example of artisanal art are steadily disappearing from our everyday lives.

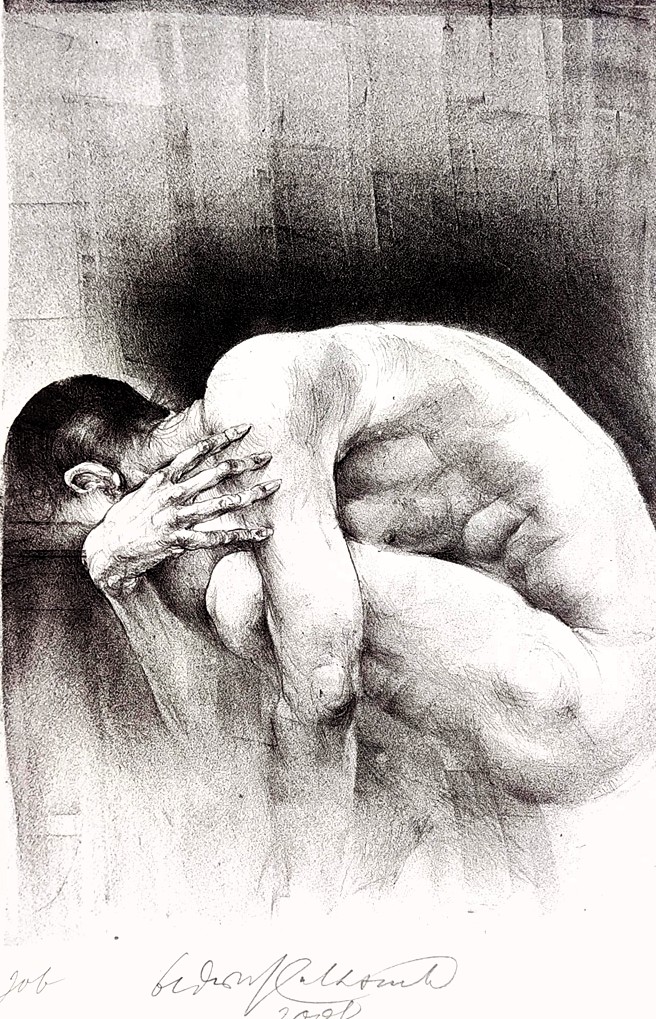

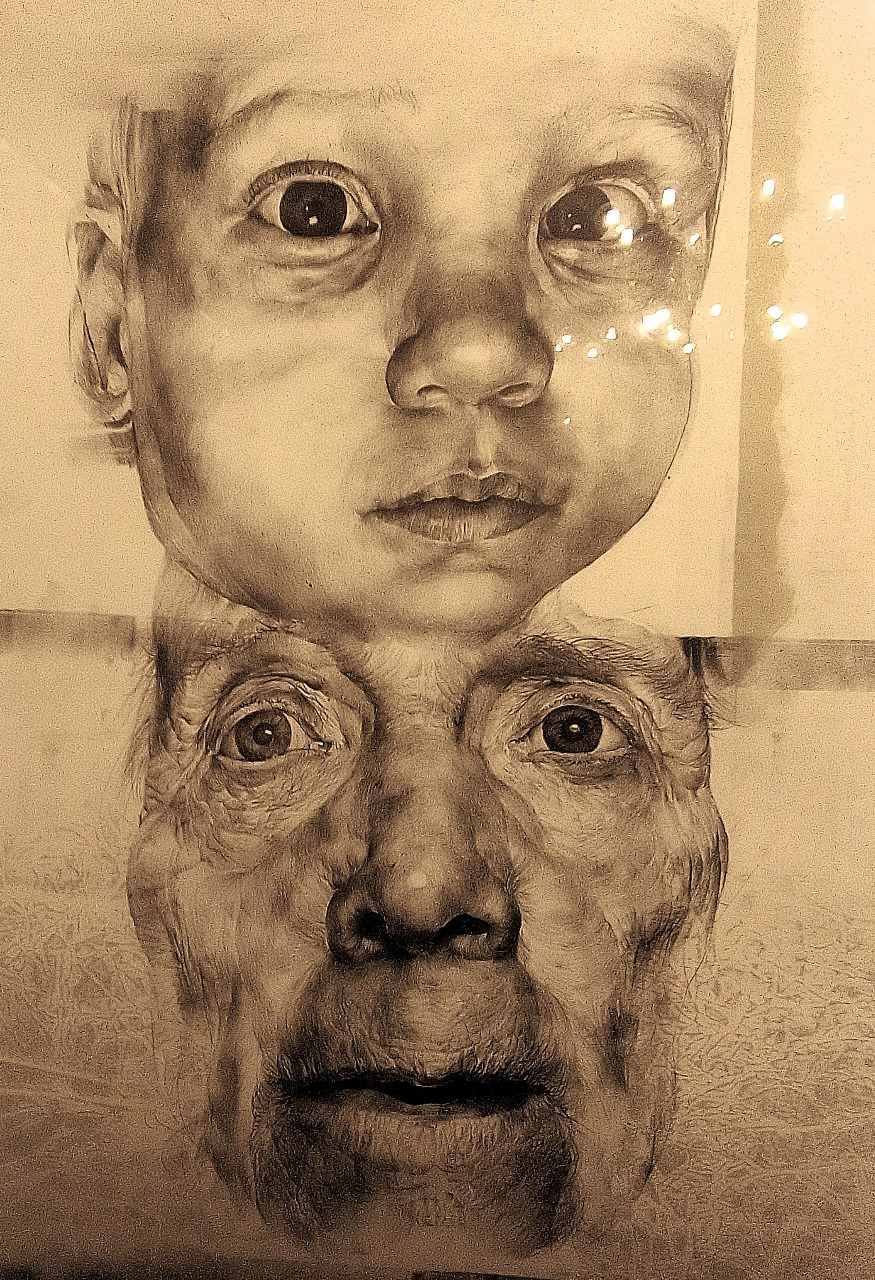

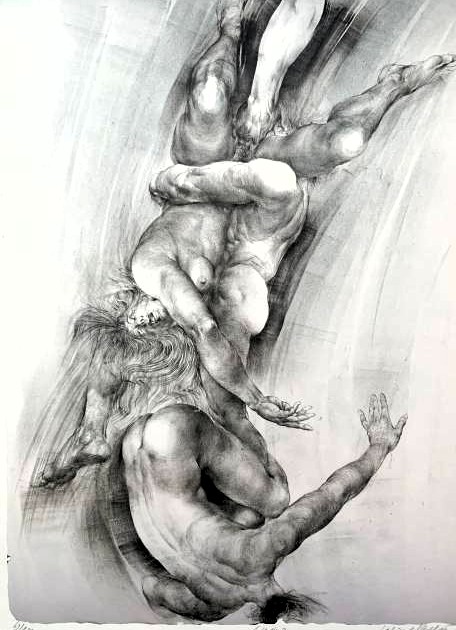

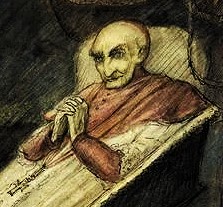

Kulhánek's graphic art was far from limited to stamps and banknotes. He was particularly interested in depicting the human body in different positions and ages. Kulhánek's naked people huddled together made me associate with the naked monster in del Toro's visually powerful Frankenstein, which I watched recently.

A fascinating idea was how Kulhánek in a series of etchings compiled portraits of people as babies and how they looked after they had aged.

Another series of falling naked human bodies brought to mind Ruben's visions of crowds of naked people plunging into Hell during the Last Judgment.

.jpg)

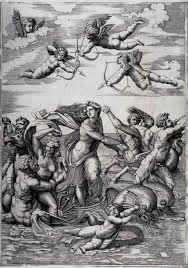

Kulhánek's assumed allusions to Baroque artists such as Rubens are reminiscent of the origins of the art of engraving. Several of the earliest etchings and their successors largely consisted of reproductions of paintings by well-known artists who thus had their works spread across Europe. For example, an engraver like Marcantonio Raimondi (1482–1534) worked closely with his good friend Raphael and transferred several of his works into prints, sold with a shared profit.

Some of Raimondi's etchings were made as being exclusively based on Raphael’s sketches. An example of this is probably Raimondi's The Judgement of Paris.

This etching has become particularly famous since the group at the bottom right a couple of centuries later became one of the models for Manet's scandalous painting Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe, Lunchon on the Grass, from 1862.

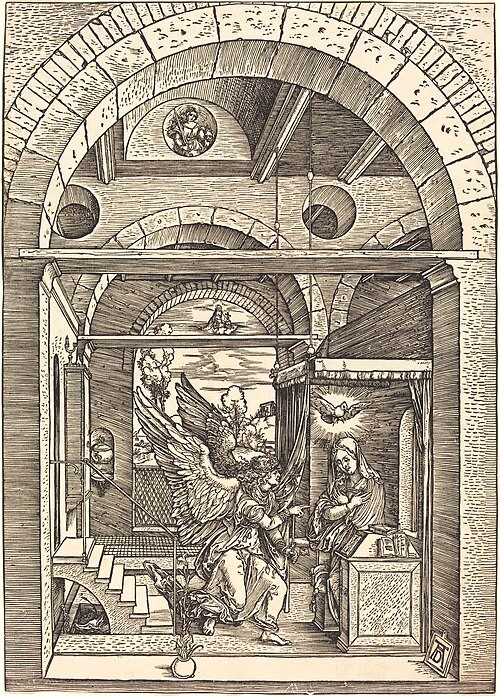

It was not only Raphael's paintings that Raimondi transferred to etchings, several artists were annoyed by the fact that he used their works without their consent. Albrecht Dürer, who for some time lived in Venice at the same time as Raimondi, the latter's birthplace, and openly confronted him for forging his graphic work and paintings, and even using his specific monogram. Raimondi made more than seventy copies of Dürer's woodcuts and etchings. As below, where he copied Dürer's woodcut with The Annunciation as an etching. Raimondi's work is on the left.

Dürer, who was just as skilled and innovative as graphic artist as a painter, was violently upset by the discovery, especially since Raimondi also was a particularly skilled graphic artist and for both of them the sale of their graphic works was a significant source of income (there are no paintings preserved by Raimondi).

After violent confrontations, Raimondi claimed that he was fully entitled to copy Dürer's paintings and prints. Accordingly, Dürer turned to the Venice government, the Signoria, which forbade Raimondi to use Dürer's monogram. However, given that the Venetian printing industry was extensive and profitable, the Signoria saw itself unable to prohibit anyone from copying the artistic works of others and selling them on the open market. Moreover, the Signoria's prohibition on the use of Dürer's monograms applied only to Venetian territories and Raimondi was therefore able to sell his Dürer copies provided with monograms outside of Venetian jurisdiction.

It is easy to understand Dürer's irritation, but also the Signoria's ruling. Before the development of photography it was difficult to take part of the works of significant artists, especially their paintings, and it was through printmaking that such knowledge spread to other artists and the general public. Raimondi"s frequent copying of Dürer’s works indicates how popular the German artist was already in his time (by the way, it was easier for Raimondi to copy the works of another graphic artist than his paintings, which were only available in the private residences of patrons, or in distant churches and palaces).

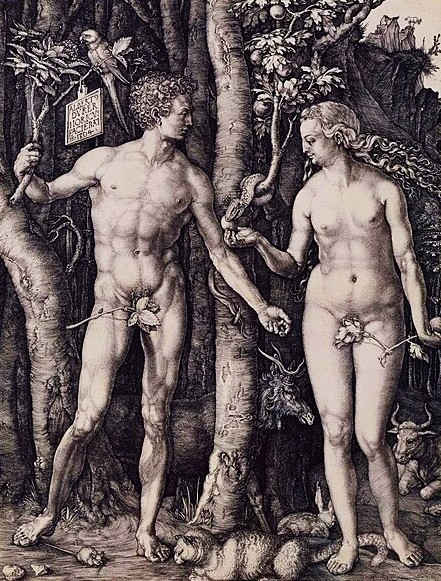

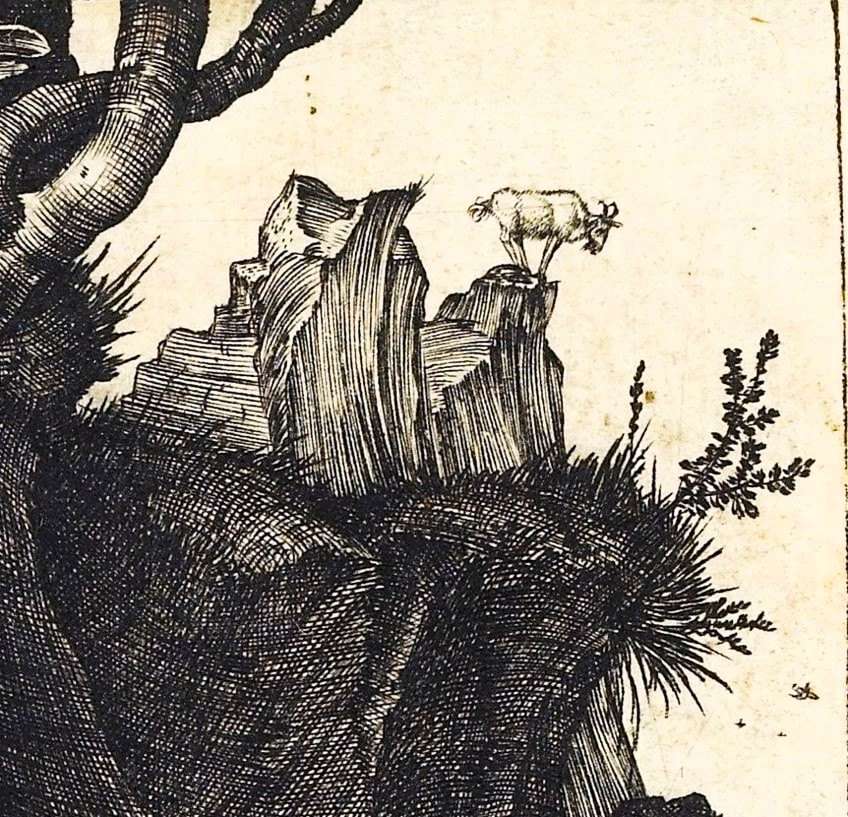

Certainly, Dürer's works are worthy of all the admiration they have been provided with, boundlessly skilfully made as they are, with an inexhaustible wealth of imagination, keen observation and a multitude of exquisite details. Take his Adam and Eve in Paradise, let your gaze move around within it and maybe let it rest in the upper right corner and there admire the image of a mountain goat looking down from a mountainous hill.

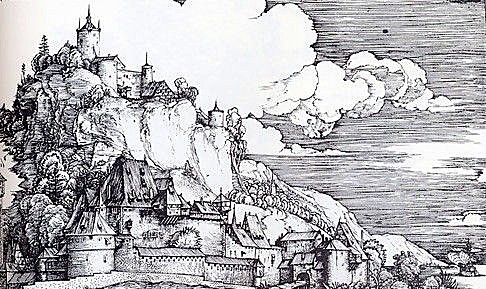

In his paintings as well as in his graphic prints, Dürer often provides us with detailed impressions of towns and villages adorning their backgrounds. Places he probably had seen and sketched during his frequent travels.

Not only was Raimondi a copyist of the works of other masters (there is no doubt that he was a great admirer of and inspired by Dürer's revolutionary art), he also created several remarkable images on his own. For example, Raphael's dream, which, despite its later and misleading title, was made before Raimondi got to know Raphael. A strange and truly nightmarish vision. A nocturnal scene with two brightly lit (moonlight?) naked, sleeping women lying on a riverbank, while small, phallic monsters crawl out of the water. In the background, people are fleeing from a burning castle and we glimpse something that appears to be reminiscent of a nocturnal Rome.

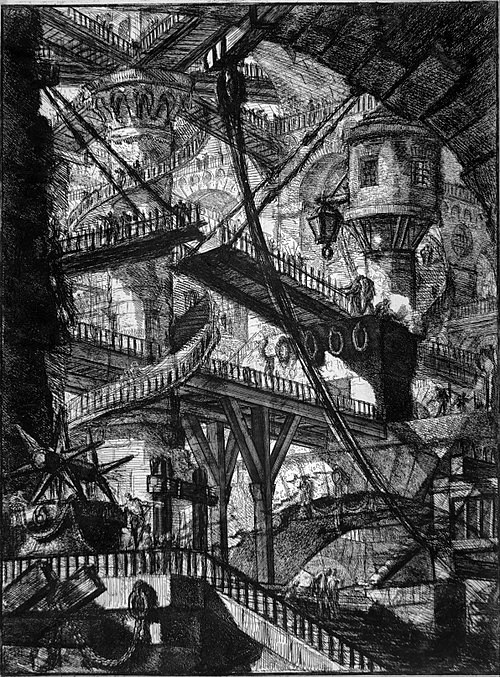

Nightmarish scenes seem to have been a common theme among several engravers. Here we find Piranesi's labyrinthinely and terrifyingly gloomy prison interiors, which, like in several of Borges' short stories, seem to encompass the entire world.

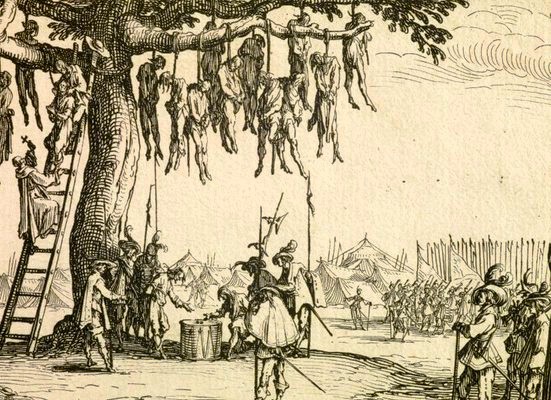

The manneristically elegant Jacques Callot, with his experiences of the horrors of the Thirty Years' War

might with a sure hand lead us into the depths of a thoroughly depicted hell.

The equally war-experienced Goya, who with a sharp eye and great pathos depicted the Napolean troops' atrocities committed on his country's civilian population, could also take us into nightmarish worlds.

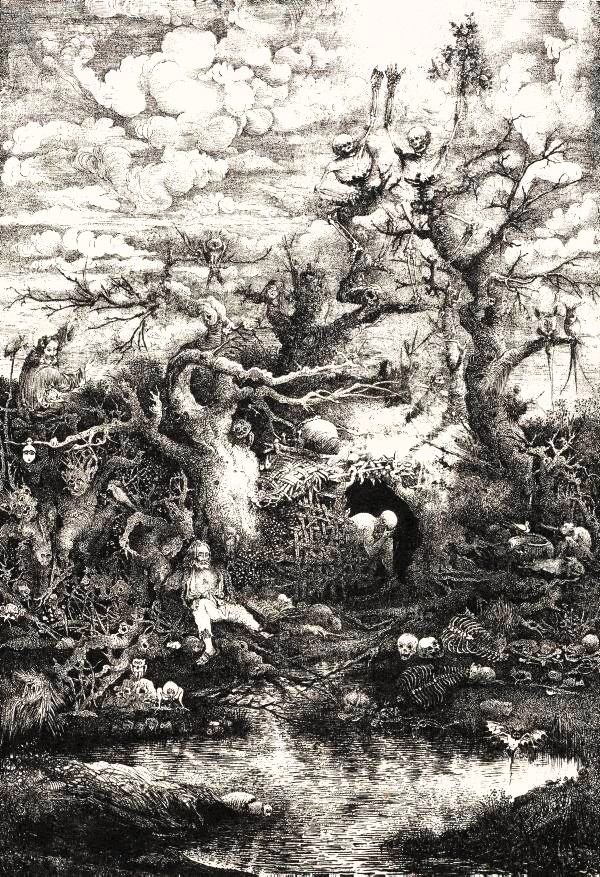

At least as detailed as Piranesi’s and Callot’s vissions are the French eccentric and graphic artist Rudolphe Bresdin’s (1822–1885) visits to a personal and strange dream world. The question is whether he could ever adapt to the world around him. At an early age, Bresdin left his messy parental home and led a bohemian existence in various parts of France, before settling in Paris, where he socialized with cultural figures such as Charles Baudelaire and Victor Hugo.

Bresdin married and had six children with his wife, whom he took with him to Canada in an attempt to make a living as a farmer. The business failed, and when Bresdin became completely destitute, Hugo and his French bohemian friends helped him and his family to move back to France, where Bresdin proved equally unable to support himself and his closest of kin. He was separated from them and finally died poor and alone in an attic in Sèvres.

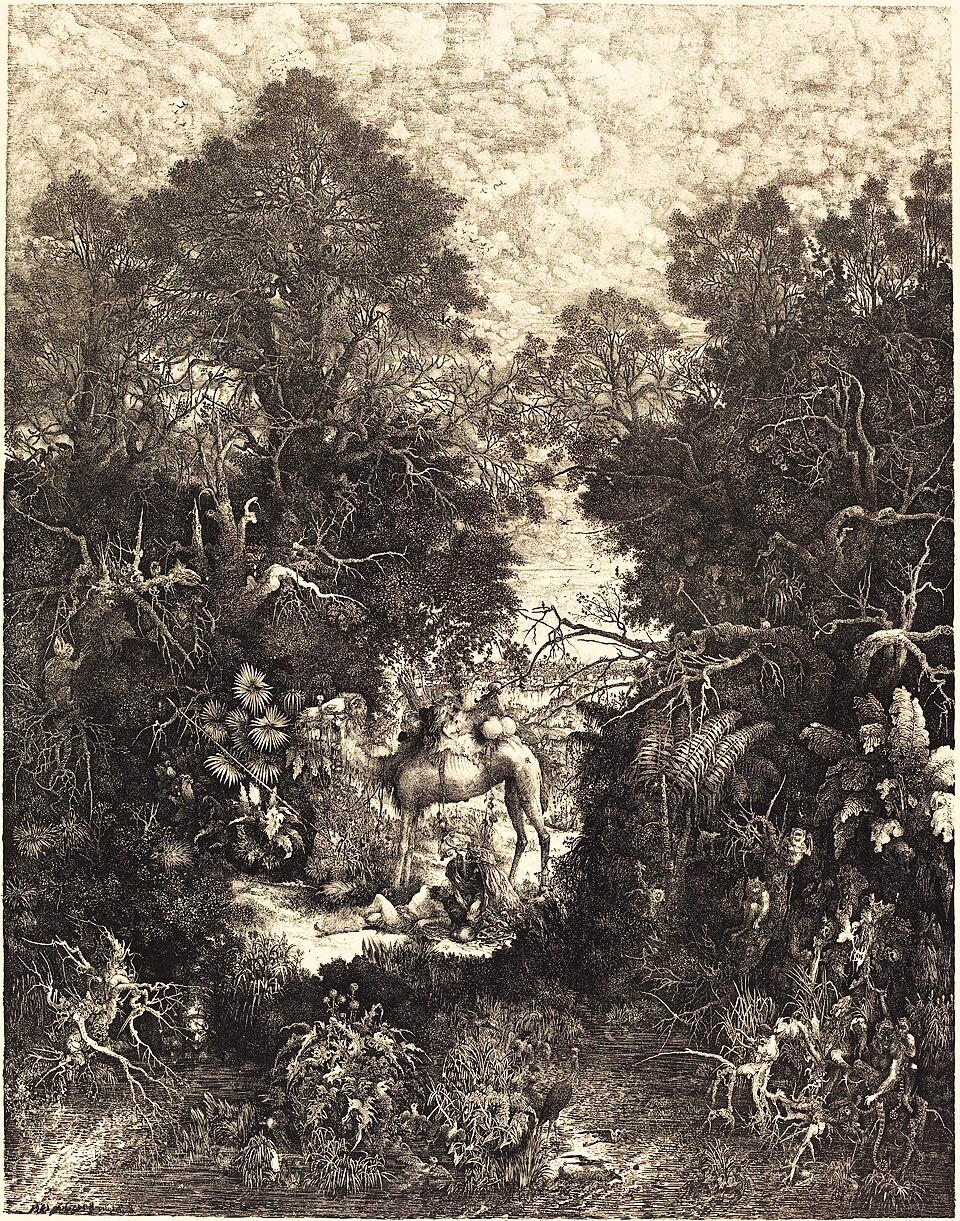

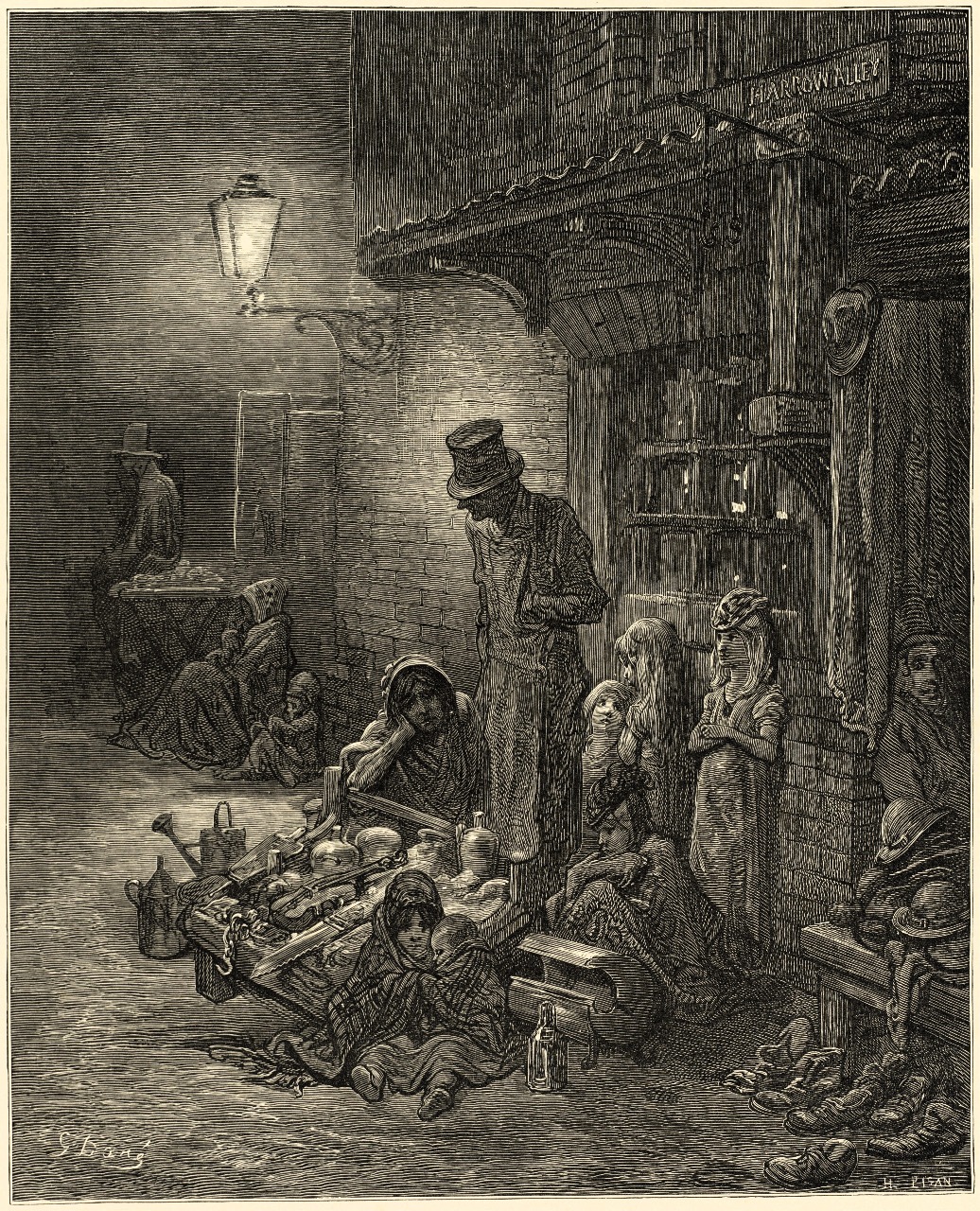

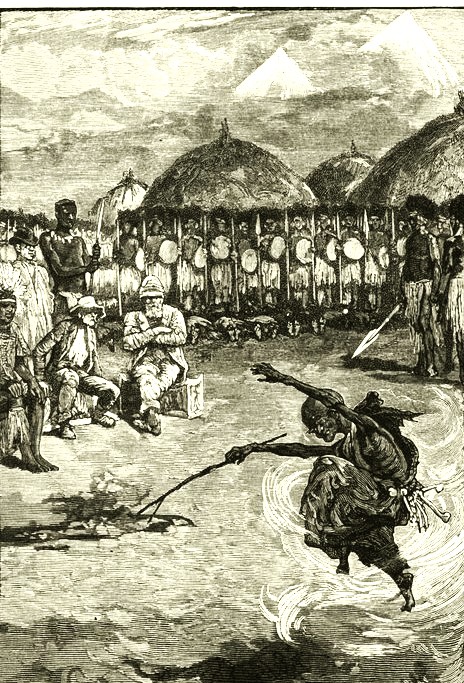

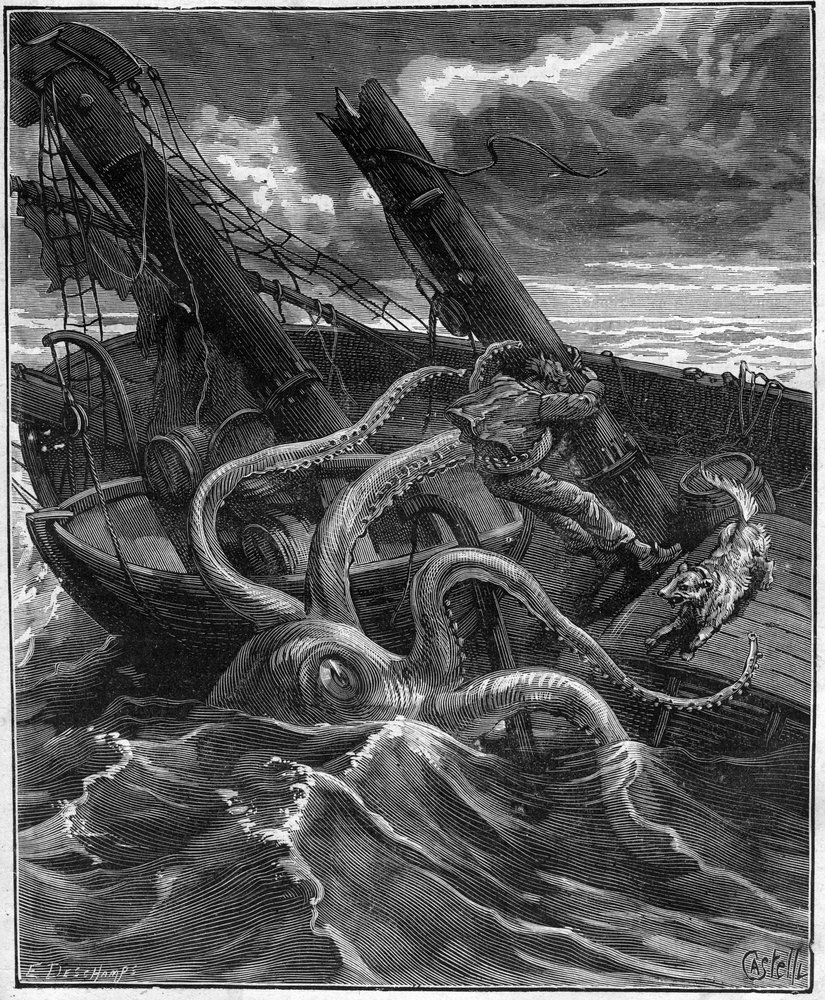

The in many respects unsurpassed and almost incomprehensibly productive Gustave Doré (1832 – 1883), was a contemporary of Bresdin. Like him Doré was a master at visualizing parallel, mythical worlds. In general, Doré drew his inspiration from literary masterpieces such as The Bible, The Divine Comedy, Gargantua, Paradise Lost, Orlando Furioso, Don Quixote, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, and many, many more.

Already early in his career, Doré achieved great international success and although he was a skilled graphic artist, he soon came to work only as a draughtsman and designer. At the height of his career, Doré had more than 40 block cutters working for him, transferring his drawings to woodcut blocks, thus producing more than 10,000 illustrations which all bore Doré's name, most of them of the highest quality.

Doré also managed to bring contemporary human misery to life in a manner that, in all its realism nevertheless spiced up by his very own visionary, mystical and rather eerie manner of depicting the world. A masterpiece in this genre is his London. A pilgrimage where every image leaves an imperishable impression.

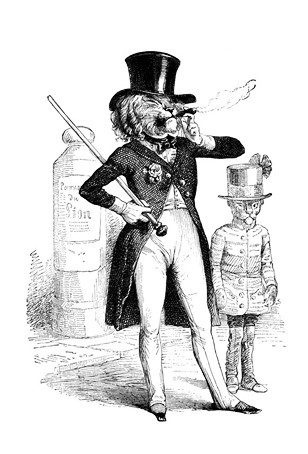

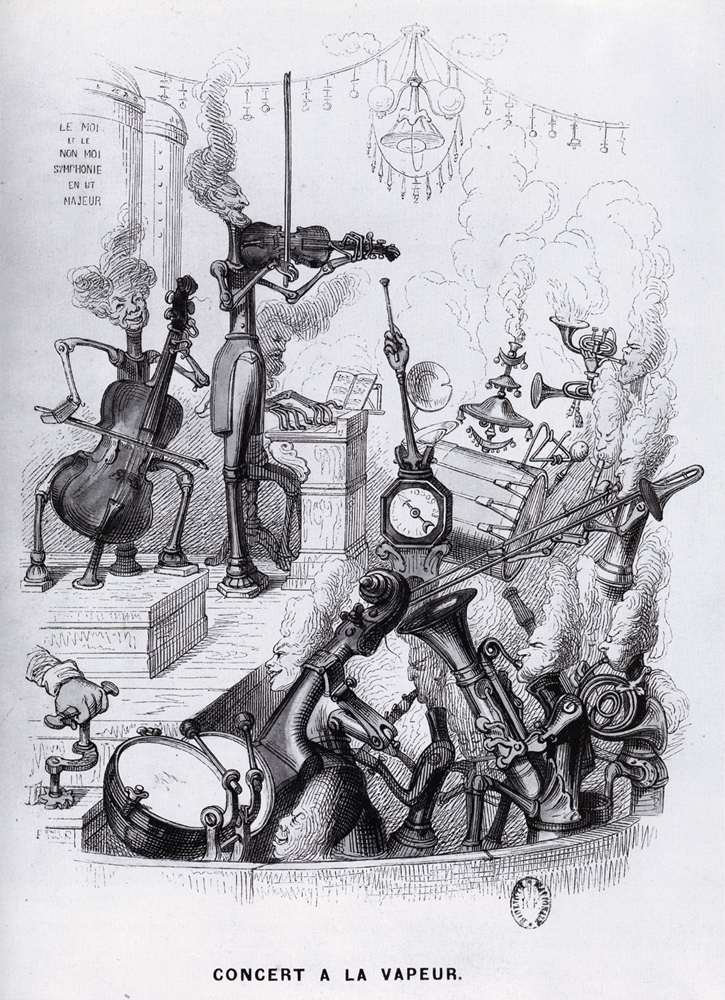

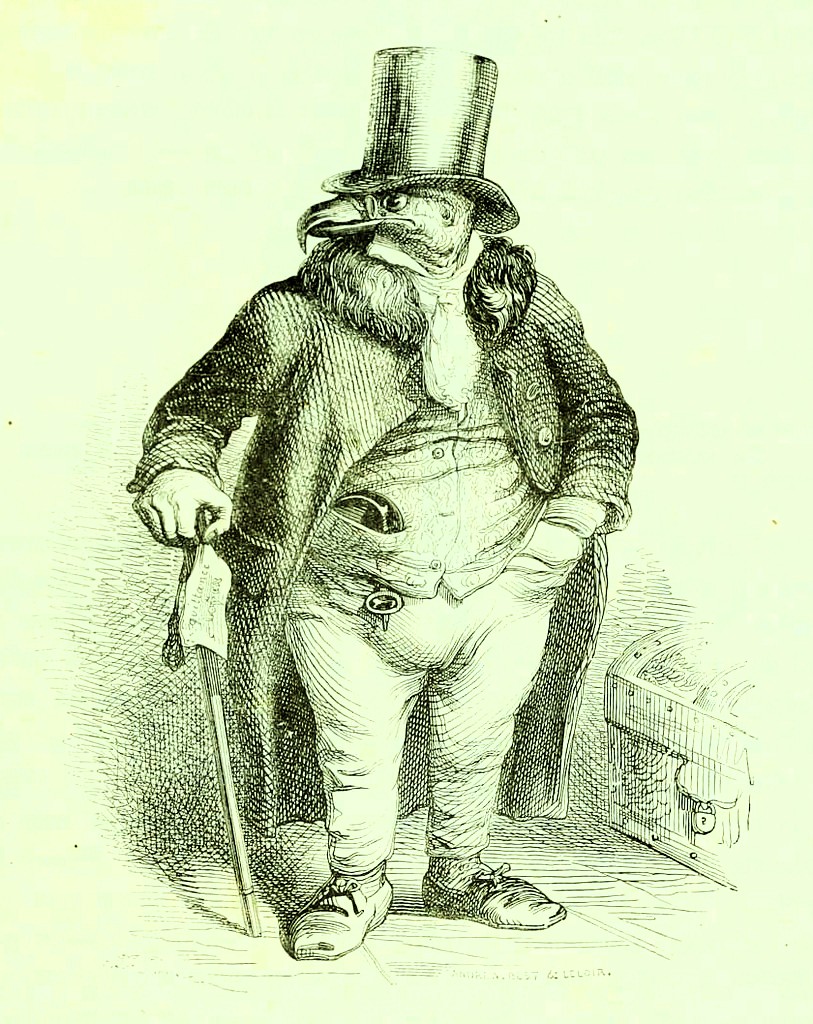

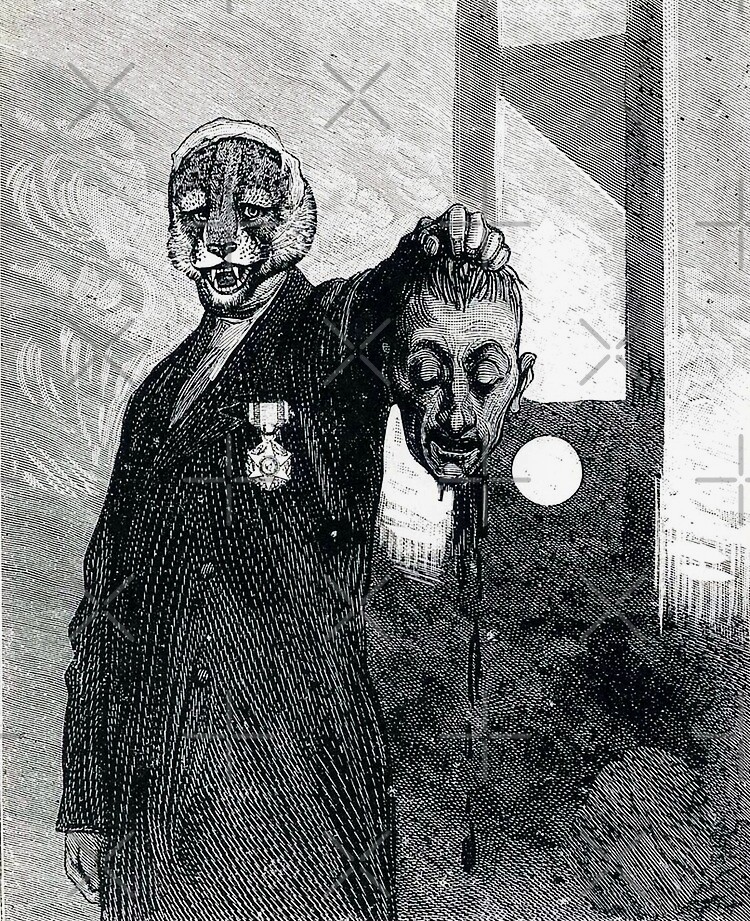

The somewhat earlier Jean Grandville (1803–1847) was also popular, with its parallel worlds populated by humanized things and animals.

Grandville's contributions to fantasy and engravings have lived on not only in countless cartoons and films, but also in surrealist art for example how it was expressed in Max Ernst’s evocative and sometimes eerie collages collected in his book Une Semaine de bonté, A Friendly Week.

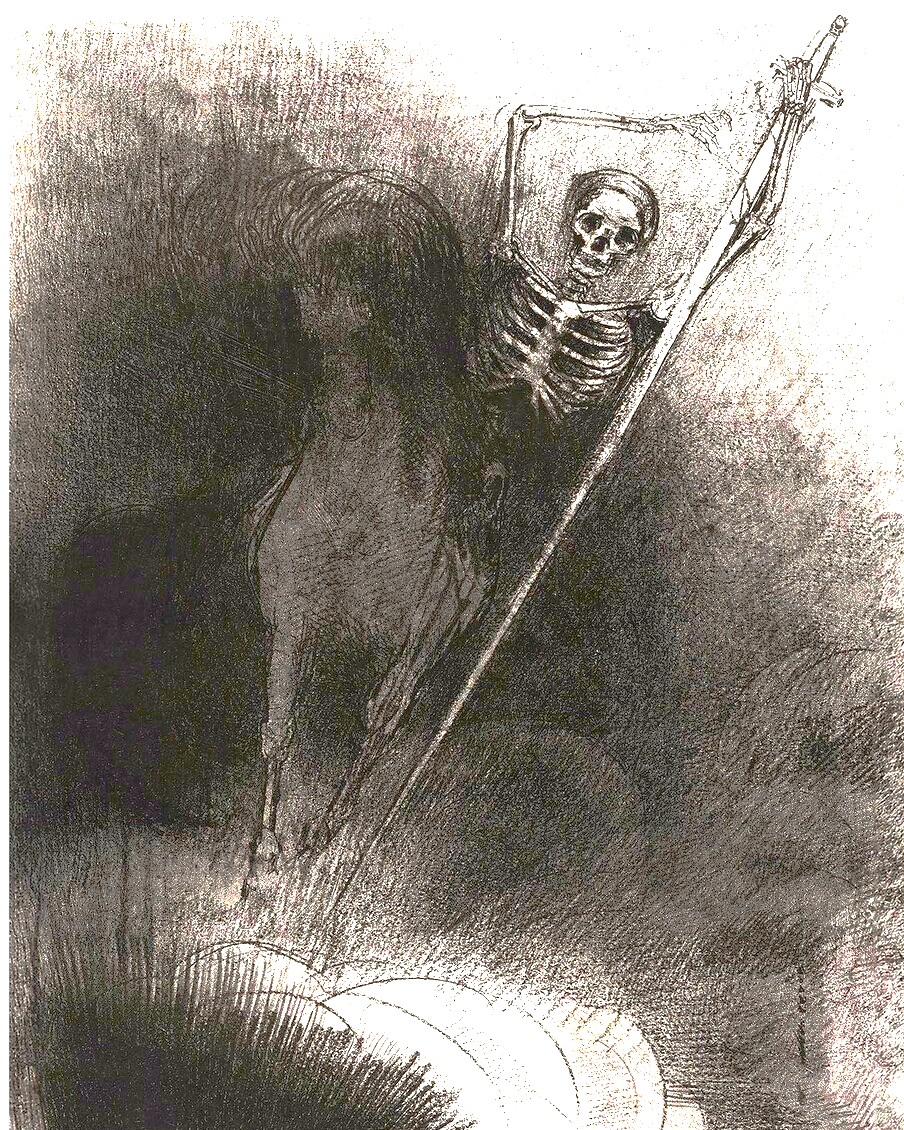

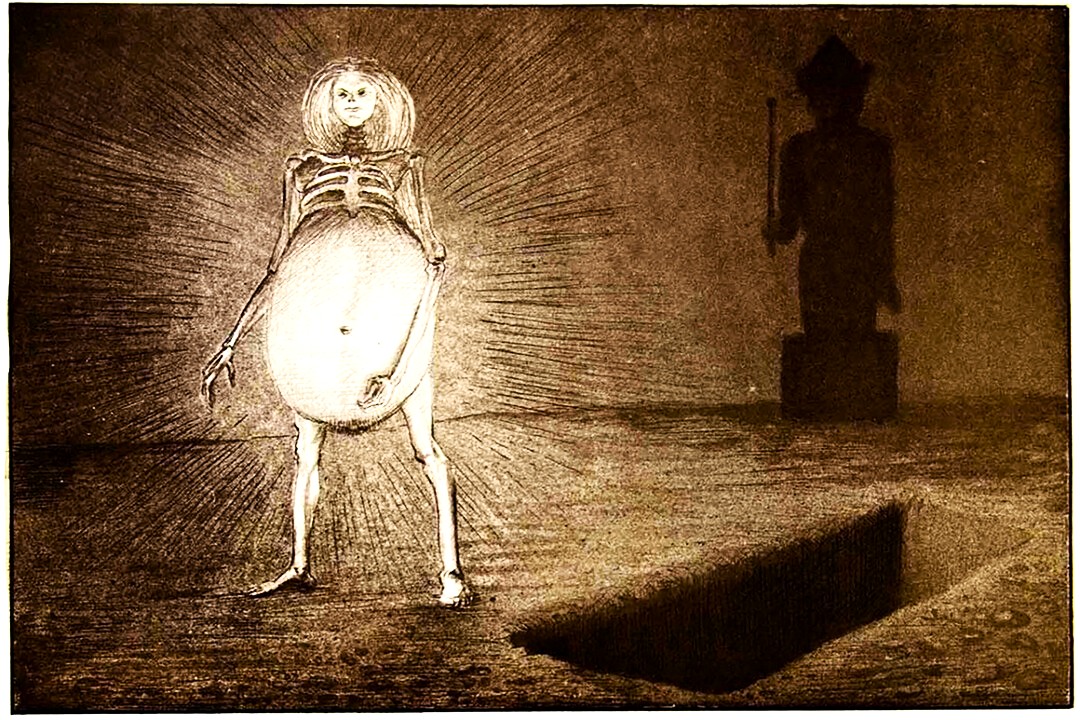

Before that, however, several graphic artists continued to enter into their dream worlds, such as the Bresdin admirer Odilon Redon (1840–1916), who in paintings, as well as in his prints, moved almost exclusively in his own sometimes dark, but nevertheless delicate, parallel reality.

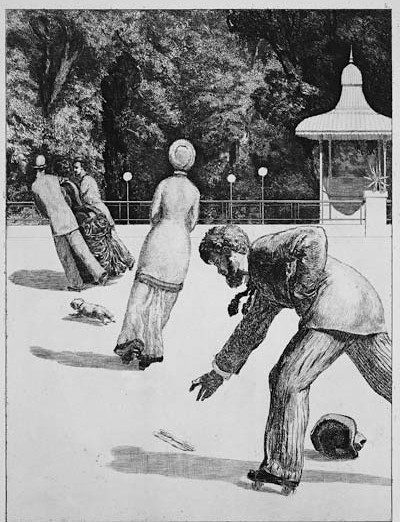

The German Max Klinger (1857–1920) was more hands-on in his dream worlds, as in his etching series A Glove, depicting how a man in a roller skating rink picked up a glove that a lady had dropped. He kept it and then became obsessed with one absurd dream after another, all of which revolved around this glove.

There are certainly erotic undertones in Klinger's dreams, but they do not cross the boundaries of decency, as is the case with the Belgian Félicien Rops (1833 – 1898), whose art often became provocative and sometimes excessively perverse. His Satan Sows His Seed, is however suggestively eerie in a way that lingers on in the mind.

Further east, the Austrian Alfred Kubin (1877 – 1959) also tends to occasionally lose himself in perversity and misogyny witin a thoroughly dark world of his own, filled as it is with monsters and deformities, but Kupin's register is wider than that of Rops and Kubin also wrote a claustrophobic and original novel about a mad autocrat and the decay of an entire city. Die andere Seite, The Other Side.

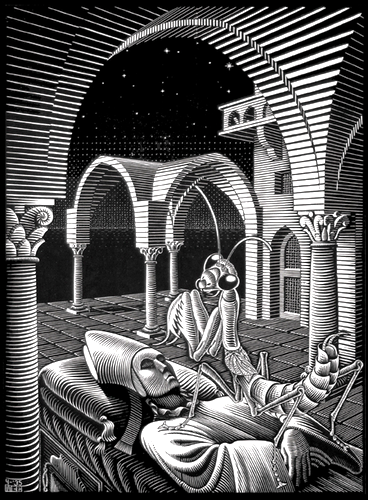

The tendency of graphic artists to depict nightmares continues into our time, and the road passes through Maurits Esher's (1898 – 1972) mathematically constructed parallel worlds, which he occasionally varied with nightmare images.

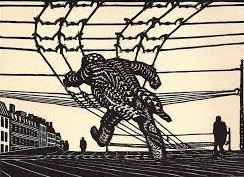

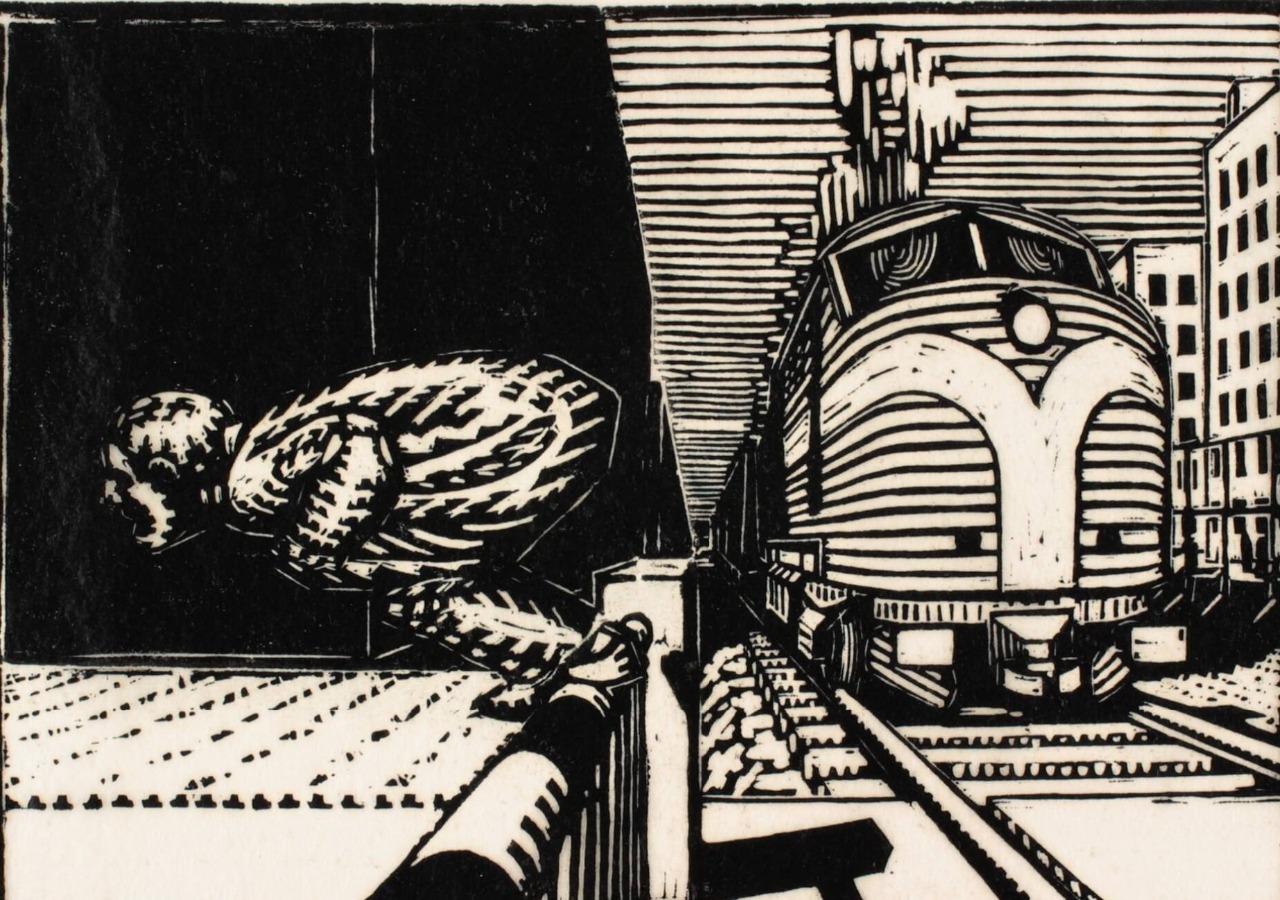

The Danish graphic artist Palle Nielsen (1920–2000) locates his graphic work within a dystopian world where people constantly are chased through often deserted urban landscapes.

Nielsen’s woodcuts works evoke something akin to a silence in ultra-rapid, where houses collapse and explosions take place as if in a vacuum.

In the graphic art of the Swede Roy Friberg (1934 – 2016), it seems as if the catastrophe has already taken place, having petrified people and their homes, unifying them with a post-apocalyptic, rocky landscape.

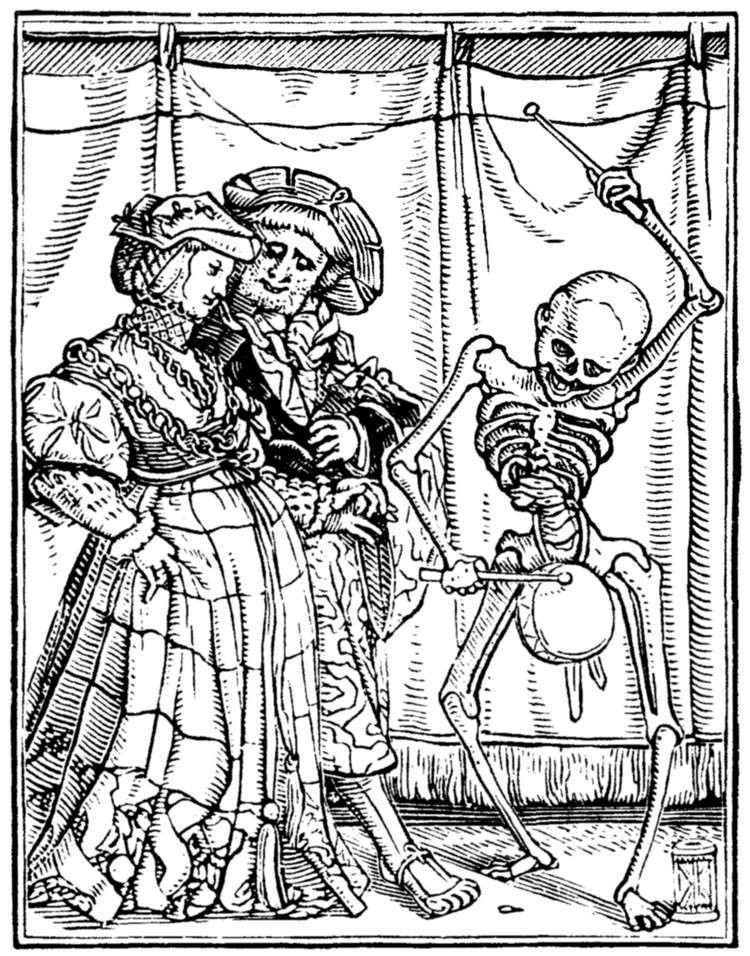

Death seems to have played a prominent role in European art, and not least the graphic artists have contributed to his presence, not least through series of "dances of death" that several of them produced. Perhaps the most important of such images where those produced by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497–1543). His suite of death dances consists of fifty-one woodcuts depicting how death visits different individuals from a variety of social classes and professions. The variety is impressive and so is the technology.

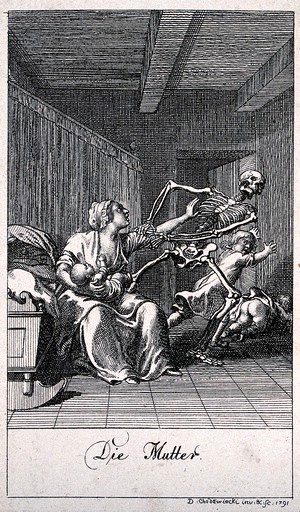

Another prominent engraver, the German-Polish Daniel Chodowiecki (1726 – 1801), made a similar suite two hundred years later.

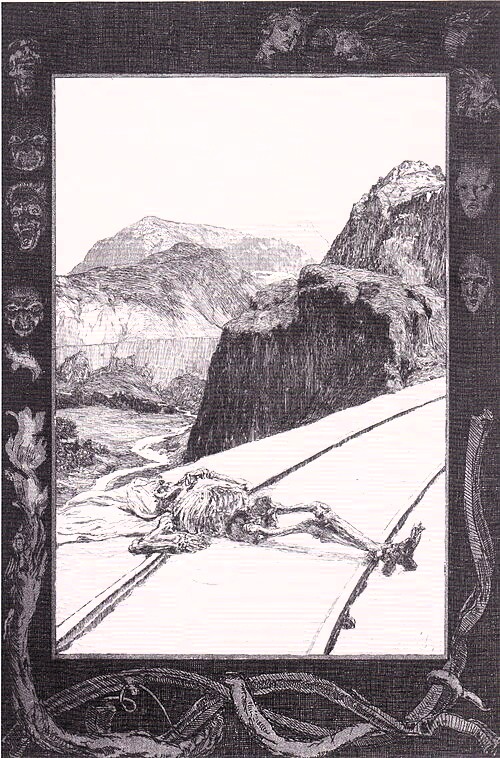

The above-mentioned Klinger had death as a prominent theme in a vast number of his etchings, among others he made a suite of ten pictures of death, which he published during a stay in Rome in 1889, but this was far from the only time he devoted himself to the motif of death.

The Norwegian Theodor Kittelsen (1857 – 1914), was well acquainted with Norwegian folk tradition, not least cheap prints found in peasant cottages, and in his engravings he often returned to death and horror.

.jpg)

Death was common in the Scandinavian so-called Kistebrev, Coffin Letters, cheaply mass produced prints sold at markets and by peddlers to be used as decorations, or pasted up under coffin lids. Their heyday was from the beginning of the 1700s until about 1850.

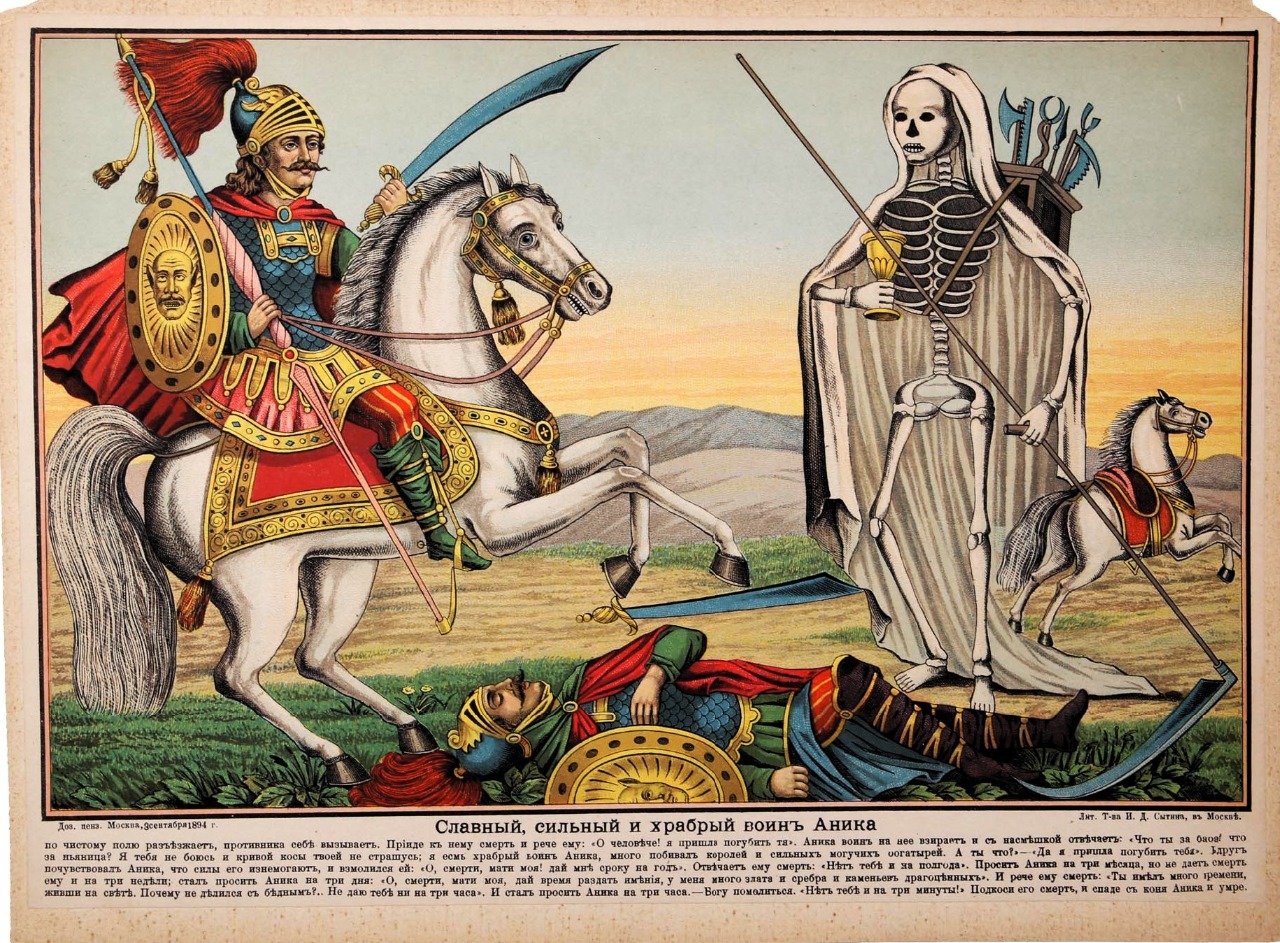

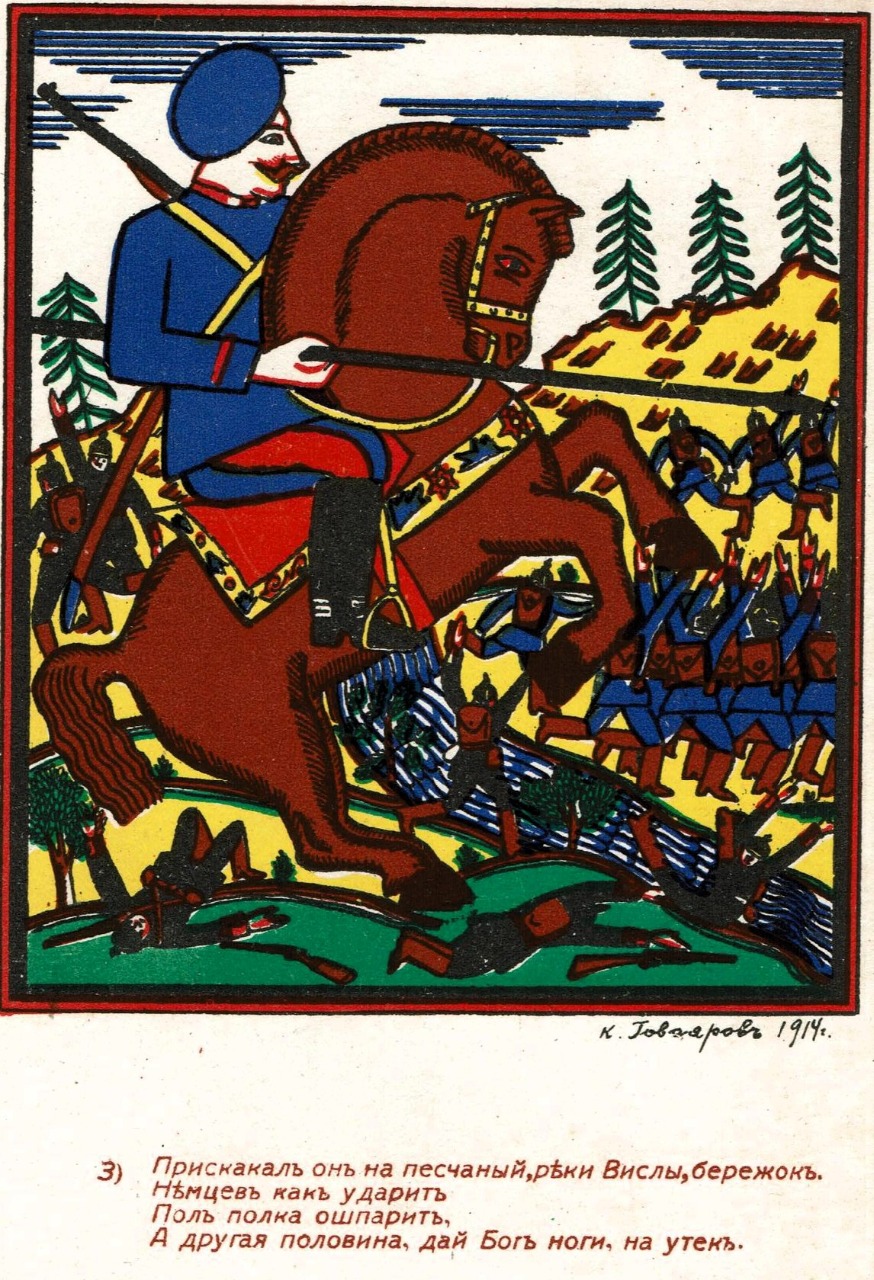

The Russian equivalent of coffin letters was Russian lubki and here we also find a number of death motifs. Death was certainly a dreaded presence among the entirety of the poor European peasantry.

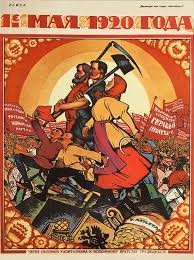

For several members of the Russian avant-garde, who had their heyday during the 1910s and 1920s, lubki came to be an important source of inspiration.

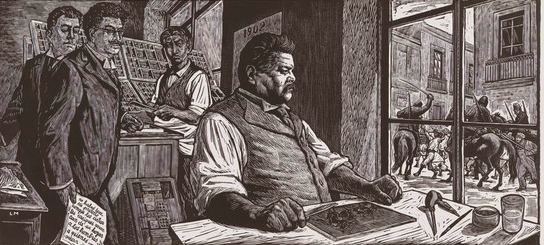

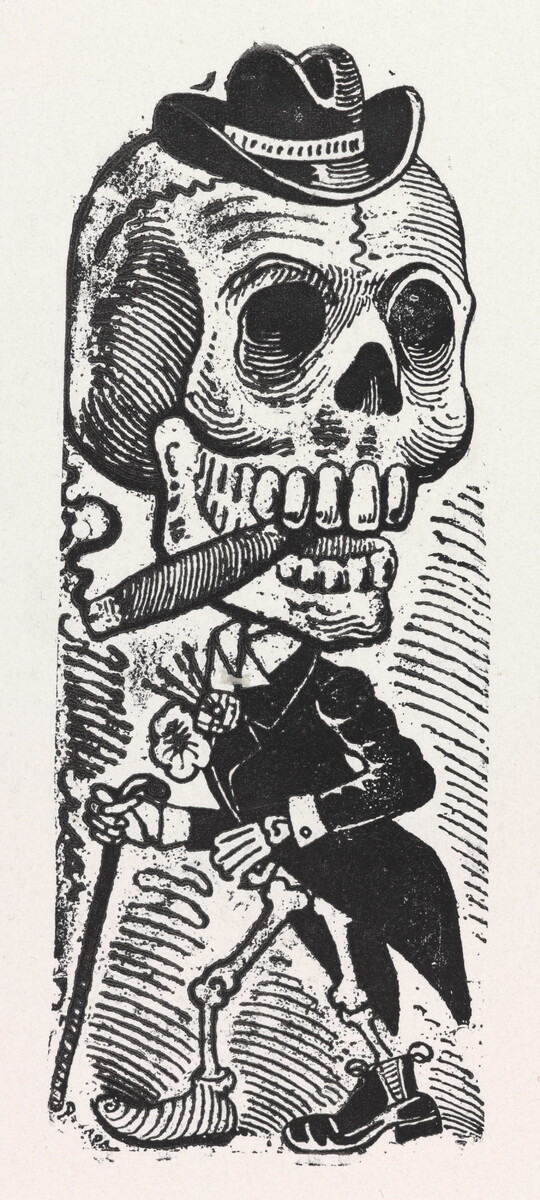

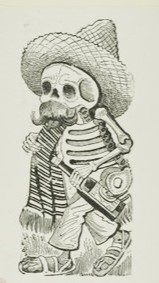

Nowhere has popular graphics been as obsessed with death as in Mexico. Its great master and inspirer of several successors, including Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, was José Guadalope Posada (1852 – 1913).

Among other things, he created the elegant skeleton lady La Catrina, which has become the epitome of the Mexican festivities around the Day of the Dead and the carnival.

Posada's skeleton also took on the guise of Mexican bourgeois, politicians, and revolutionaries and has become an integral part of Mexican culture.

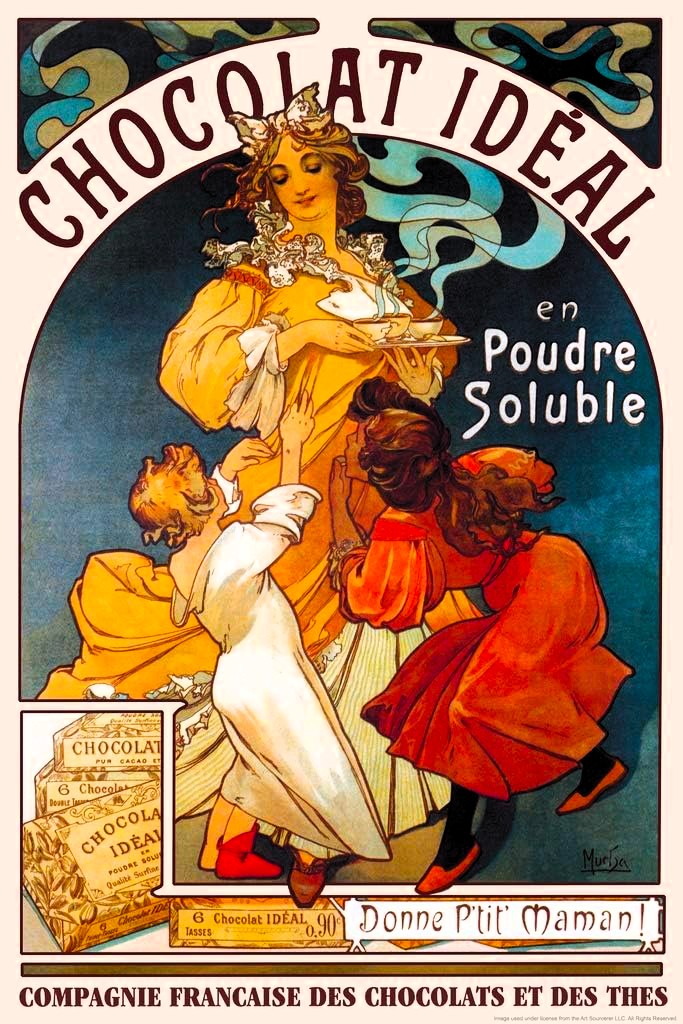

Of course, not all graphic art moves within lugubrious regions, etchings and woodcuts are no longer its most common means of expression. For a long time, graphic artists have devoted themselves to a variety of genres and techniques, which also have and have had their masters. For example, in advertising.

.jpg)

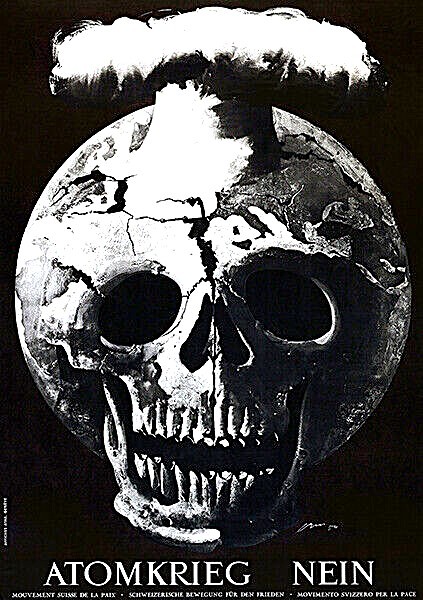

Political posters

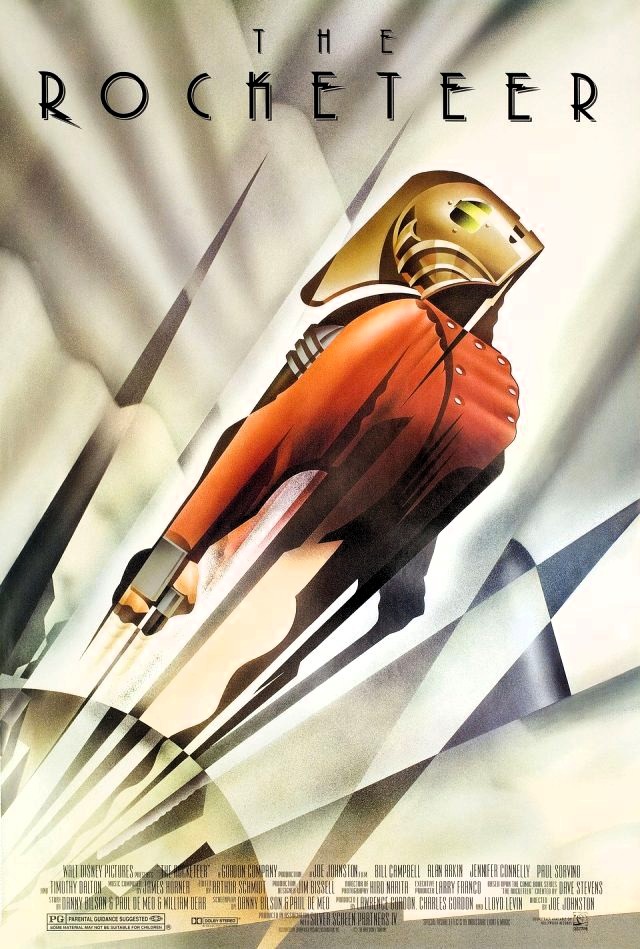

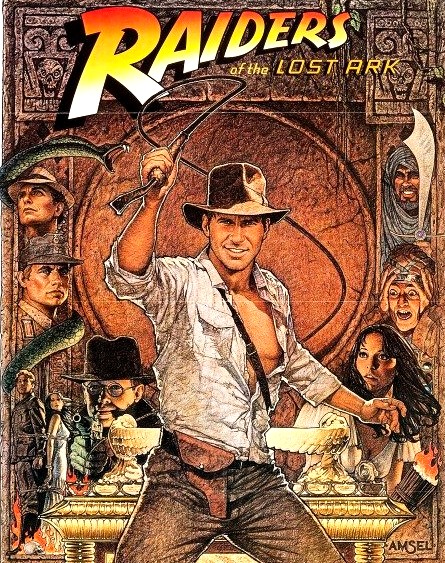

Movie posters

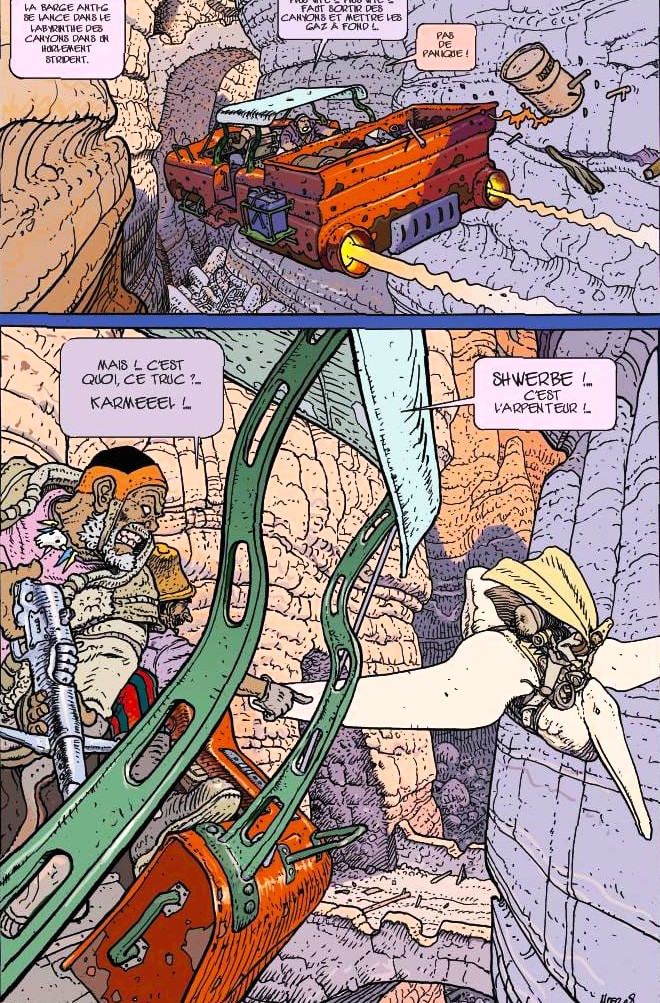

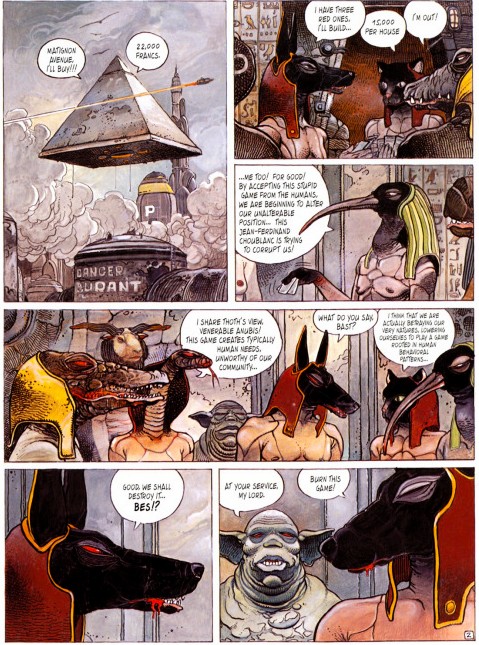

Comics magazines

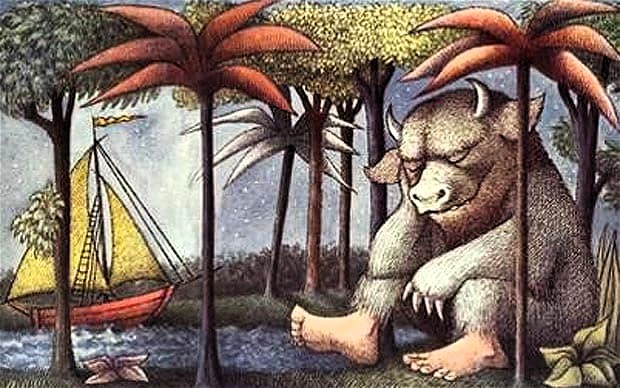

Book illustrations, an art that reached a peak in the latter part of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

and has continued to exercise its fascination, mainly in children's literature.

While talking about graphic art, it is easy to overlook the mastery that several artists have put into their skills, which often involve patience-demanding detailing.

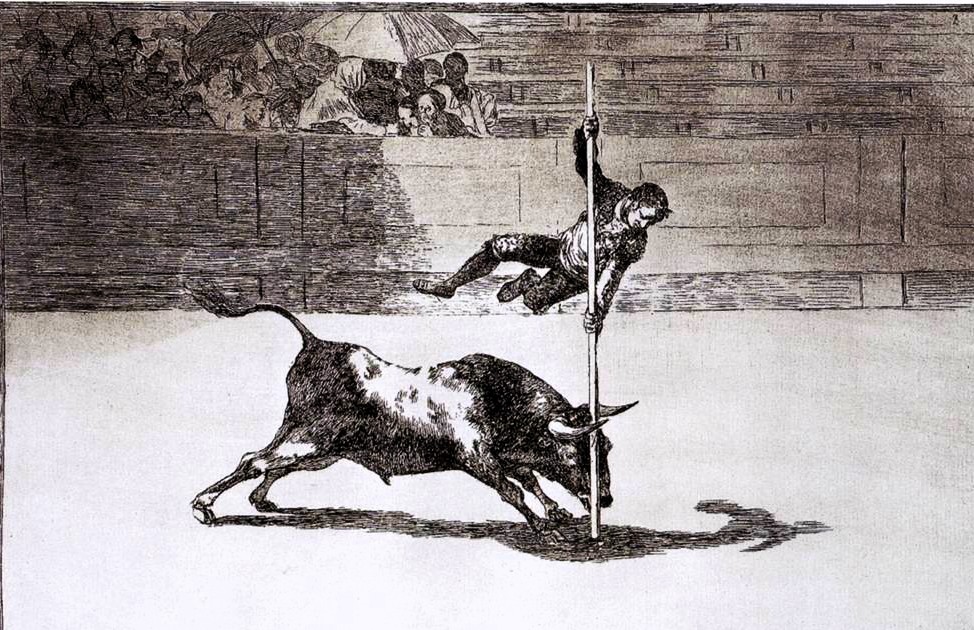

Consider how Goya organized one of his graphic sheets. The centre of gravity is on its left side, which lays in shade and where the audience has gathered. This supports an illusion of the bull's violent rampage by stressing its movement into the void of the arena. Howver in the middle of the picture charging bull furious onslaught is stopped by the acrobatic matador's vertical cane, with which he for a moment halts all movement as he is hovering in mid-air, making the viewer wonder: "What will happen next?" As in a photograph, Goya has stopped time.

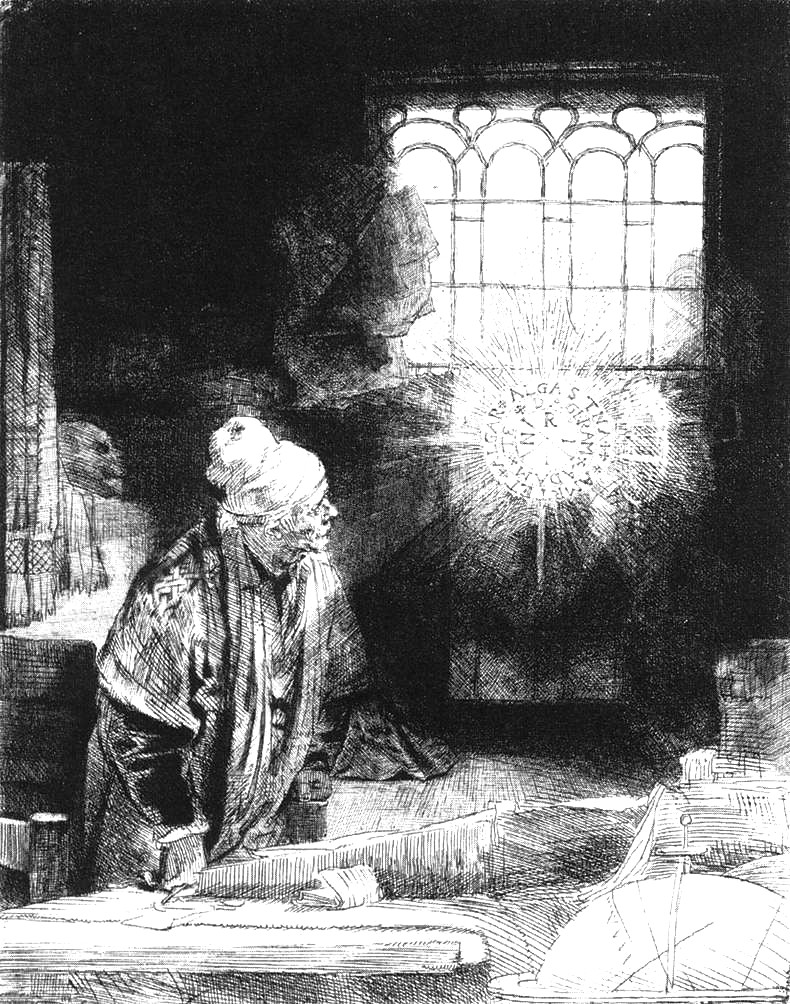

The Dutch Baroque master Hendrick Goltzius (1558 – 1617) has been called the last professional engraver who with the authority of a skilled painter was able to apply a lush creative ability and flowing lines to such an extent that he came to have a great influence on his European artist colleagues. A tribute which appears to be somewhat too exuberant, especially considering Rembrandt’s graphics, which a few years later perfected the art of engraving.

However, that does not deprive Goltzius of his championship. Goltzius had a deformed right hand, after having injuring during a fire. He was thus forced to put a lot of force into his arm - and shoulder muscles and persistent training gave him a powerful schwung in his lines, perhaps also a reason for the care he constantly demonstrated when it came to emphasizing the musculature of his figures. He also claimed that his deformed hand made it easier for him to get a secure grip on the burin, the etching needle. On several occasions, Goltzius depicted his distorted right hand, as below in a picture he named The Hand of Judas.

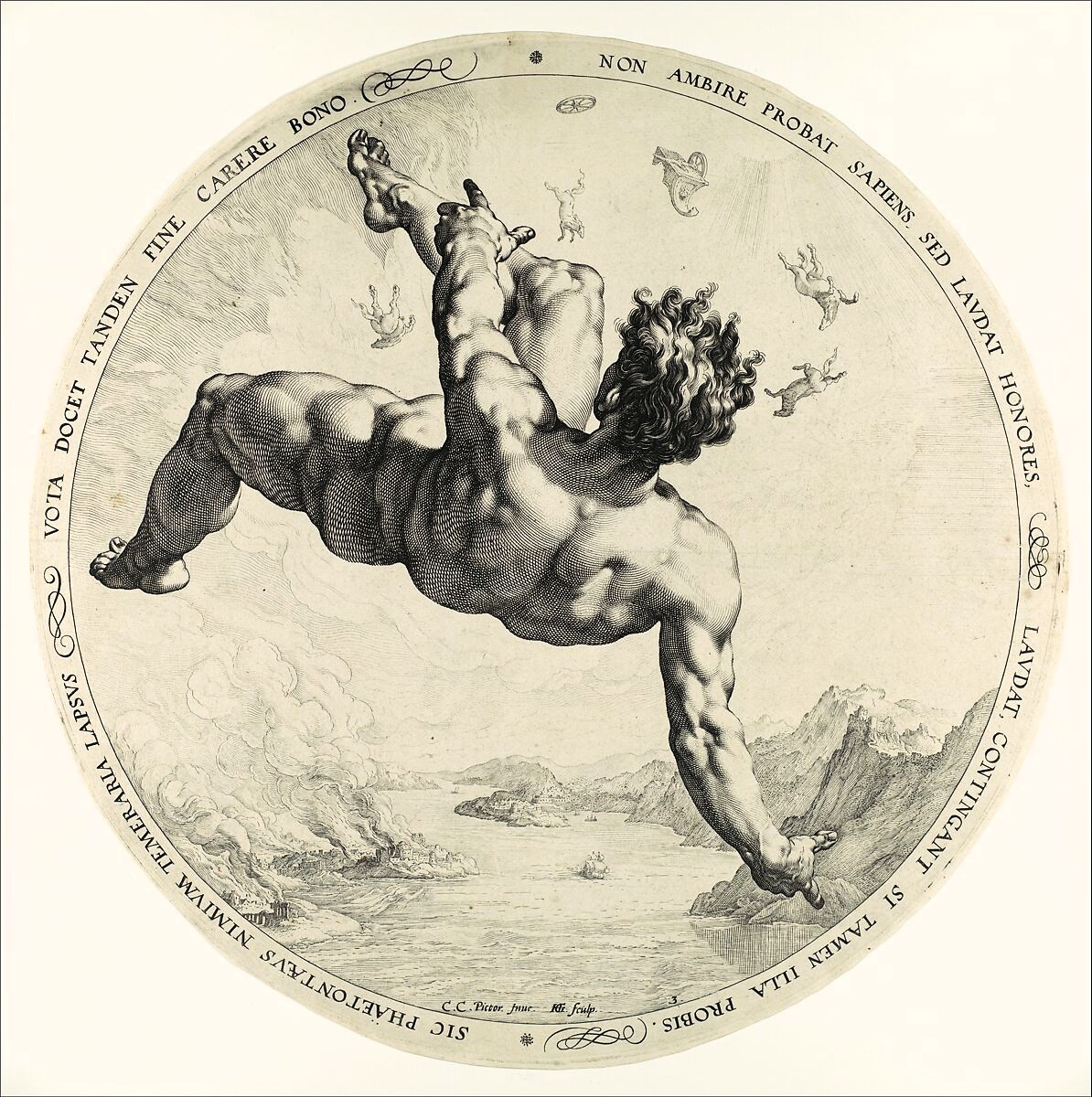

Muscle play and a bold abbreviation are demonstrated in his version of the falling Phaeton.

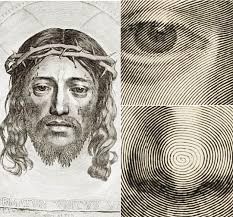

Graphic artists were often tempted to expose their superior skill. Like the Frenchman Claude Mellan (1598 – 1688) who with a single circular motion with the burin created a perfect Christ face.

Otherwise, I am especially fascinated by another image of St. Peter of Nolasco being brought to the altar by two angels. Obviously, that etching, like so many others, is based on an oil painting by another artist, but I have not been able to identify the original. However, Mellan's picture is a masterpiece on its own accord, not least because of the refined lines, but also in the motif itself.

An aged saint is while sitting and reading carried by two angels who, in their efforts, do not seem to possess any heavenly powers. This while they are watched by a number of monks standing reverently in an airy church. I have no idea why St. Peter is carried to the altar while he is immersed in reading his book, nor who the saint was, other than that he was raising money to free Christian slaves from the Muslim Maghreb.

When I now read through what I have written about my findings in the history of printmaking, I find that they have taken a lugubrious direction. Goya, Kubin, Klinger, Redon, Doré and others with them seem to have had a penchant for the darker sides of existence and imagination.

Perhaps, I am also attracted to such things, or it may simply be because at the time of writing I dins myself in Prague and the Czech Republic, where it seems to me that art and everyday life might be endowed with a somewhat gloomy macabre, or gallows-humorous, undertone.

Five years ago, after one of my visits to Prague, I wrote a blog post Flu, masks and witches in which I described, among other things, the terrifying monsters that threaten Czech children, especially during Advent, and which for centuries have haunted Bohemian and Moravian folklore.

Child-devouring Barboras and their demonic mistress Barbora/Frau Perchta, who have their freiendly counterparts in the Christmas-gift-giving saintly figures of St. Nicholas and Good King Wenceslas, whose opposite is the terrifying Krampus/Čert.

That such a now perishing folklore has crept into the art world is perhaps not so strange. In any case, during my current stay in the Czech Republic, I heard about an art project that fits well into this context.

About 200 km east of Prague we find the village of Luková. All of its 750 inhabitants are not permanent residents, several of the well-preserved old houses are now populated by people who only spend their weekends and holidays there.

The village's church, dedicated to St. George, was in 1352 built of locally mined stone, replacing an earlier wooden church. However, time has not been gracious for the originally beautiful church building. War, theft and fires have constantly ravaged it and repeated restorations have fundamentally changed its appearance; altarpieces, statues, church bells and the baptismal font have been taken away. Today, it is probably only the church pews that are more or less intact.

When a funeral was held in 1968, the roof collapsed, some of the parishioners were injured, but none seriously, and the result was that the church was definitively closed.

In 2012, Jakub Hadrava started looking for a suitable degree project to conclude his studies at the Faculty of Design and Art at the University of West Bohemia in Pilsen. He had begun to think about how church buildings for centuries had been at the very centre of people's lives and thinking:

The church was a place where you met God, a moral paragon, in my opinion it was a place that was primarily intended to promote people's goodness. The fact that several of these buildings now are empty and decaying is a reflection of the state in which so many of today's people are living, how they have deteriorated mentally and how their entire life situation threatens to fall apart. I wanted to draw attention to this and make a casual observer realize how important the place they happen to find themselves within in really is, especially if they have ended up in a church room, a holy sphere.

Hadrava came up with the idea of transforming an abandoned, dilapidated church into a place of insight and meditation. He thought about how he could stimulate a visitor’s contemplation through some kind of installation.

He found a 2007 publication called Endangered Churches listing the large amount of abandoned churches in the Czech Republic. The descriptions were brief and the photographs were often outdated.

Hadrava sought out a number of these churches and inquired about their use, owners, and the future planned for them. He found that most of them were now owned by private individuals, or companies, who demonstrated a limited interest either in preserving them or even less in letting them be available for an art installation. However, Hadrava eventually ended up in Luková.

The dilapidated chirch was still owned by the Catholic Church, which found Hadrava's plans interesting – according to the local parish leaders, the proposal had a good Christian foundation and could possibly lead to the church being revived.

Hadrava had originally envisioned some kind of "abstract, minimalist" installation, but the peculiar mystique and tragic history of the place made him change his mind. It was not only that the population of Luková, through its almost thousand-year history, had suffered and often been decimated by plague and war, the latter in the form of the devastating Hussite rebellion of the fifteenth century, but a host of other wars as well, not least the thirty-year one in the 17th century and the First one that devastated the village and then World War II with its Nazi terror regime, followed by the forced deportation of Luková's German-speaking population, which was by then larger than its Czech population and made the village generally known by its German name – Sichelsdorf.

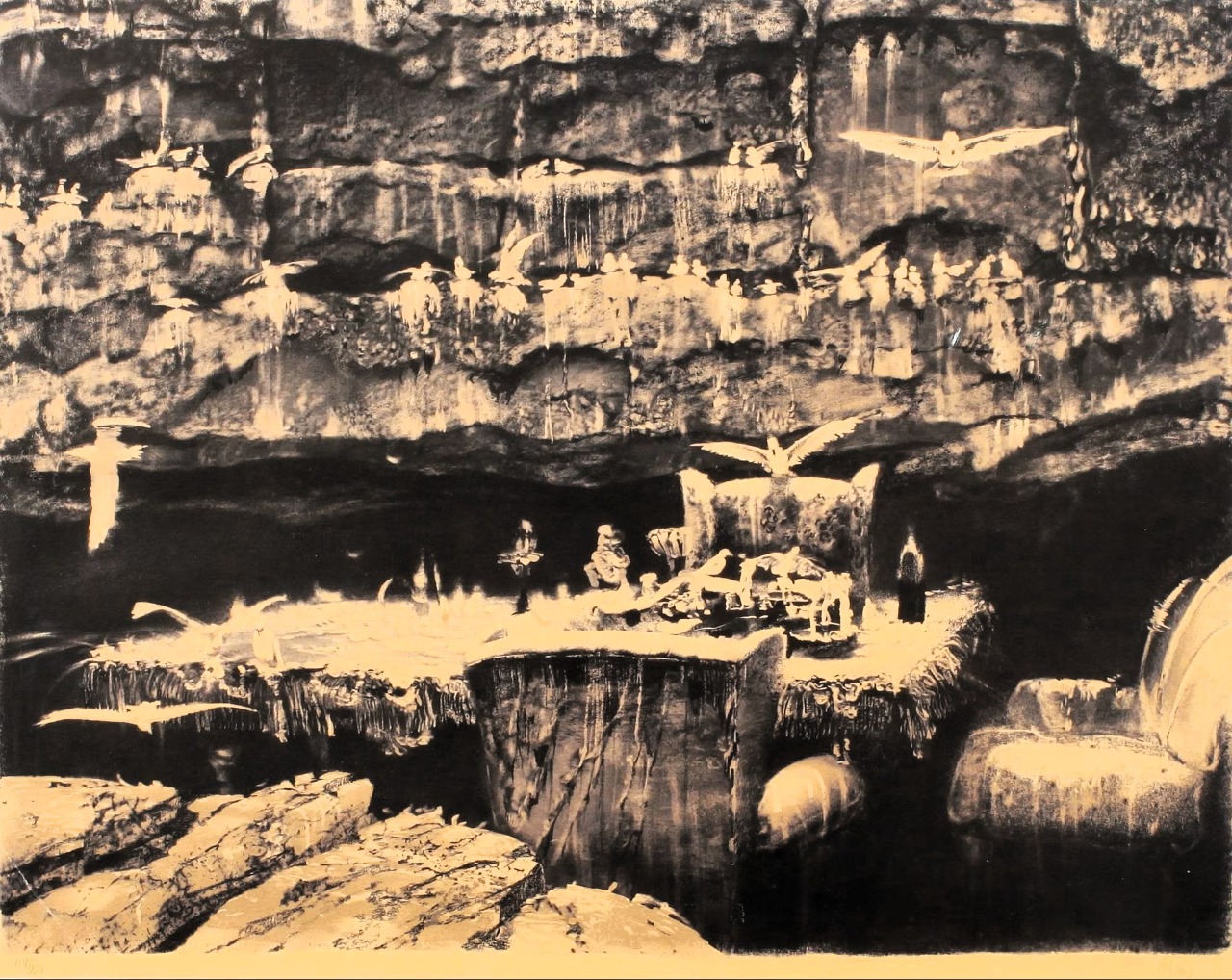

In the dilapidated church, Hadrava felt that he sensed the presence of all these missing people's ghosts and decided to populate the church with 32 life-size plaster figures. Because they represented now forgotten people, they took the form of ghost figures.

Since the church was closed and abandoned, Hadrava first wanted to preserve it in that manner – after all, it represented a past that for many modern people had been forgotten, a closed room, like a museum. The church's large windows were preserved and a visitor could look through them into the mass of the dead.

However, as Hadrava's project became increasingly known through newspaper reports and TV spots, more and more visitors sought out Luková. These visitors also wished to be allowed access to the church. Luková's congregation therefore decided to keep its ghostly church open every Saturday between March and October. More and more visitors from all over the world are now flocking to share the experience of sharing space with tangible ghosts from the past.

.jpg)

A strange and perhaps even scary feeling that deepens after dark.

In any case, Jakub Hadrava's installation has been something of a success and has put Luková on the map. Donations from the increased number of visitors, which now amount to 25,000 euros, have enabled the parish to repair the roof and occasionally mass can be held in the church as parishioners carefully take their seats among the ghostly plaster figures.

However, there is a concern that the installation concept might be tarnished and popularized to such an extent that a sensationalist mass tourism could kill Harrava's original idea – to honour the memory of the dead and create a meditative atmosphere within a church space that would bring a visitor closer to history and the positive values that church and religion once were passing on to our ancestors.