TIME FOR TIME: Reflections on the concept of time

Autumn has come, it's cold and dark in the apartment, but outside the sun is shining from a clear sky. As soon as I came out of doors, I felt the warmth of the sun and savoured in deep breaths the fresh air saturated with the scents of autumn. Even though I find myself in a metropolis the centre of Rome remains something of a rural idyll, with many trees and large unkempt parks, far from being as well-ordered as they are in Paris.

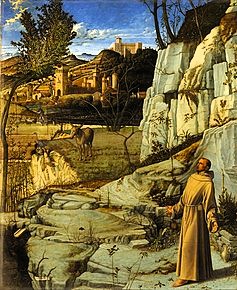

On the way to the outdoor café, I paid a visit to a church, something that has also become something of a habit. I like the devout, meditative tranquillity, just as I in a Muslim country I appreciate the serenity of mosques, although it is now been a long time since I have been to such places.

It was the end of a funeral act and I remained discreetly in the shadows. From my place behind a pillar, I saw the coffin being carried out by six men dressed in black. When the mourners had left the church, I sneaked out almost stumbled on the on the funeral wreaths that had been laid out on the church steps.

Somewhat downhearted I sat at my coffee cup, pondering about the flight of time, death’s obduracy and how it already had taken several friends from me. However, but was soon enlivened by the gentle warmth of the sun. After all, I was in Italy. A fact that sometimes surprises me. I can't really understand how fate brought me to a city I had been fascinated by and wanted to live in already as a child, more than sixty years ago.

Life has been good to me and in the midst of all its incomprehensible tragedy, I feel undeserved of the happiness that has been bestowed upon me. There are certainly concerns and problems. But... nevertheless. With a content sigh I thought of San Francisco’s canticle to the sun, written among the mountains and lush meadows of Italy:

All praise be yours, my Lord, through all that you have made,

and first my lord Brother Sun,

who brings the day; and light you give to us through him.

How beautiful is he, how radiant in all his splendour!

Of you, Most High, he bears the likeness.

All praise be yours, my Lord, through Sister Moon and Stars;

In the heavens you have made them, bright

and precious and fair.

All praise be yours, My Lord, through Brothers Wind and Air,

and fair and stormy, all the weather’s moods,

by which you cherish all that you have made.

All praise be yours, my Lord, through Sister Water,

o useful, lowly, precious and pure.

I finished my coffee and walked up to the nearby park around Villa Doria Pamphilj, with its meadows, pine forests and marble statues, all of which have lost their heads. I sit down on a bench overlooking the castle.

Warming my face in the sunshine before I took out the book I had brought with me in my coat pocket, Juan Mascaró's selection of Upanishads:

Like a falcon or an eagle, after soaring in the sky, folds his wings for he is weary, and flies down to his nest, even so the Spirit of man hastens to that place of rest where the soul has no desires and the Spirit sees no dreams.

What was seen in a dream, all the fears of waking, such as being slain or oppressed, pursued by an elephant or falling into an abyss is seen to be a delusion. But when like a king or a god the Spirit feels “I am all” then he is in the highest world. It is the world of the Spirit, where there are no desires, all evil has vanished, and there is no fear.

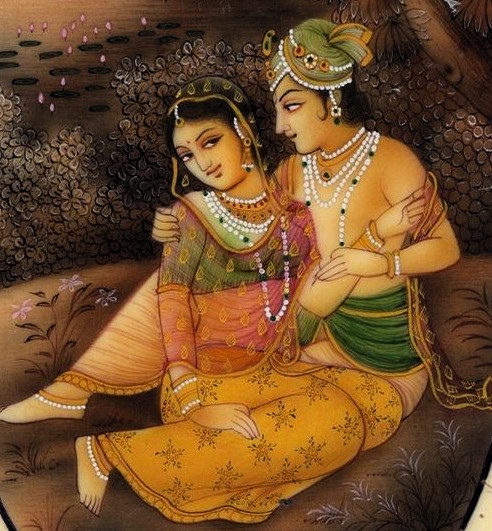

As a man in the arms of the woman beloved feels only peace around, even so the Soul in the embrace of Atman, the Spirit of vision, feels only peace all around. All desires are attained, since the Spriit that is all has been attained, no desires are there, and there is no sorrow.

It is Yajñavalkya who, one thousand two hundred years ago, spoke thus to Janaka, the king of Videha.

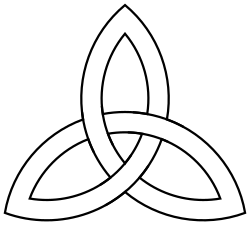

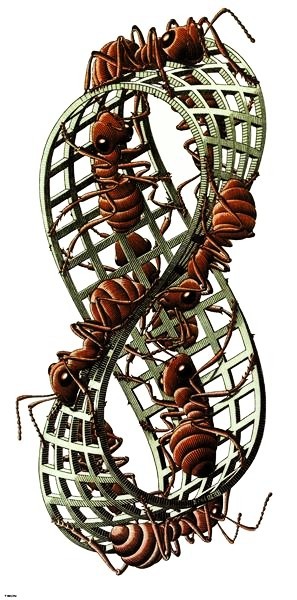

As so often when I have read something thought-provoking, I closed my eyes and began to reflect upon what I had read. Recollections of Dark, a German TV series I had just seen, popped within my head. An extremely complicated story; a labyrinth of different time periods where characters and events changed, disappeared and resurged in an increasingly complicated merry-go-round that was to prove to be not so merry after all. However, towards the end, entanglements were to some extent dissolved and it was explained that everything has taken place around the nucleus of a time dimension symbolized by a triquetra.

This is the image of a kind of knot that has been cherished by modern New Age movements, but which origins are lost somewhere in the Bronze Age. The triquetra is by many considered to be an image of the junction between the past, the present, and the future, thus illustrating how these different aspects of time periods are intertwined.

It was Ivan, the son of our Dominican friend Mayra, who recommended the series to me the last time we met. I have known Ivan since he was a little boy, now he is over fifty years old. We share an interest in horror films, for which he has a taste that is consistent with mine. Therefore, I trusted Ivan's judgment when he claimed that Dark was worth watching, especially as it provided him with an enriching view of time as an incomprehensible phenomenon.

Ivan, this somewhat corpulent man with a beard, could it really be the same little menace I once knew and played with? Sure, I recognize him and we still get along well. But, nevertheless – the difference is evident. And what about 6me? Who am I compared to the man I was at the time when Ivan was just a little kid?

Thinking of my friends from the past. Some of them I haven't seen for years, mainly because I've often lived far away from them, in different countries. But, when I meet with my best friends from the past, it's as if time doesn't exist. We have just as much fun together as we had then... five, ten, twenty years ago, while other acquaintances that I have seen again have become total strangers to me. When I meet them, they might have been the same as before, I don't know, but they don't tell me anything. Some of them I found to be completely changed – often for the worse. And me? When I got to know Ivan ... and now. Is that the same man?

I sat on the bench in Villa Pamphilj's park and thought about time. There I was in the middle of the present, not knowing what would happen within a minute and with memories stretching far back in time, for certain encumbered with several incomprehensible gaps.

The future? Unfortunately, I knew some of it, especially unpleasantness like deadlines that have to be met – bills, doctor's appointments, repairs and other necessary expenses, a lot of misery that must be covered by a strained economy. However, there are also things that I can look forward to with joy. As my mother used to say when she lived alone in the loss of my father – “We must always have something joyful to look forward to.” She lived to be ninety-six years old, and kept her clear mind to the end. Nevertheless, the future is actually hidden from us, and there are for sure many unexpected threats to our wellbeing – at any moment I can be run over by a car, or suffer a fatal disease, not to mention a creeping senility and all the terrible things that might haunt my loved ones.

There on the bench, I asked myself the same question that people have wondered about for thousands of years – What is time? It amused me to think about all the things that time travel can mean and how it can mess up life – like in Dark and ... What is the human imagination not capable of? What a miracle is human thinking!

I looked at the book I was holding in my hand and remember how, many years ago, during lectures in Lund, I was gripped by mysticism, especially as it was presented by Indian wisdom teachers such as Yajñavalkya – that our perception of our self, of time, of our own existence, is just a chimera, an illusion. The result of limited thinking. We are in fact part of something much bigger than ourselves, than the world, something boundless, cosmically vast – like the drop of water compared to the Ocean.

When we die, we merge into this ocean. Become part of it ... Like the drop of water when it is united with the sea, it is not obliterated, it continues to exist, but as an integral part of the boundless eternity. For me, it was a beautiful thought.Time is a natural presence – days pass by, the clocks tick on, our bodies are aging, reminding us of what we have done and what we have not done, what we should be doing and will not do.

As a former teacher, I know quite well that Time has a permanent home in language – present tense (is), past tense (was), perfect (had), past perfect (had been), future perfect (will have) and future perfect continuous (will have been). Through our ancestors' genes, time lives in our bodies and continues in our children. It is rooted in our brains, through memories that have characterized our lives – injustices we have committed and been subjected to; Triumphs and setbacks, an unhappy or happy childhood, bullying and admiration, discrimination and pampering. Time rests deep within us and characterizes our lives – the past, the present and the future.

Time is an essential dimension in the world of physics – length, width, height and time. Time controls the molecules and is found far out and everywhere in the Cosmos. It is integrated in both the small and the large. It lives within every being, within everything.

On my way home I watched the people pass. I had ended up in a strange mood. I knew that each person within him/herself carried his/her very own time dimension.Time is money!

Planes, rockets, subways, taxis,

there's no more rest, no more respite

Time to love? Man, you're dreaming!

Such is the law: run or die.

Time is money!

And the sun, it has to be disciplined,

it always wants to go to bed.

Hellish land, you have to curse it

if you don't want to spin faster!

Time is money.

And then he calmly and quietly celebrates love, closeness, community and nature. But once again, hustle and bustle break in.

I'm cautious.

empty promises aren't for me.

There's no merchant selling time.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jt0kVkw9lvA

Time is constantly moving forward. It never returns. We cannot reclaim the opportunities we have allowed ourselves to miss, prevent the mistakes we have made, all the misery we have caused to ourselves and others. The Swedish poet Nils Ferlin wrote:

A crisis here, a crisis there.

Times they are so busy. —

The one you desire came for a visit.

Too bad it was for both of you.

She knocked — once or twice.

Put her ear against the door

No one was home. She had to go.

What else could she do?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uKtwiYP60K8

Many of us, perhaps most of us, are excited and tormented by our individual time. Time seems to be something that we assume we own. We believe that we must constantly protect our cherished time, so that no one deprives us of it. Time thieves are plentiful; within our own family, in our workplaces.

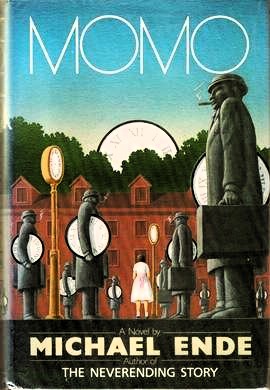

And not the least, we steal our own time, waste it on unimportant things. Unforgettably expressed in Michael Ende's novel Momo or the Battle for Time, with German accuracy he gave his book the long title Momo. Die seltsame Geschichte von den Zeit-Dieben und von dem Kind, das den Menschen die gestohlene Zeit zurückbrachte, The Strange Story of the Time Thieves and of the Child Who Brought the Stolen Time Back to People. The child who in this strange novel takes back people's stolen time is the poor but positively cheerful and eccentric Momo, who single-handedly saves us from the devastating time thieves.

The parasitic Grey Men appear out of nowhere and deceive people by deluding them that they can become wealthy if they save their time in their Time Bank. A lie as good as the one that is constantly honked at us by the slippery henchmen of commercialism, who have deceived us into believing that everything can be measured and bought with money, not least time.

Get rich quickly and easily, without much hassle on your part. Give us what you have of your excess time and we will invest it and double its value. Everything has a value, even time – but let us take care of it all, you don't have to bother managing your own time.

The grey-clad, grey-skinned, bald non-people claim to represent The Time Savings Bank, an institution that provides "time savings" – Time deposited in this bank can then be recouped with interest. Fast cash!

And people give the grey men their time, believing that at a later date they can regain an increased time. Soon life where the Grey Men have ravaged becomes sterile. They have stolen all “wasted” time — pastime, distraction, relaxation, amusement, art, fantasizing, daydreaming, strolling, rest, and sleep. Everything has become grey and uniform, levelling has spread like a deadly plague and transformed the lives of time savers; devastated colour, joy, imagination and love. Time, like art, has acquired a false, commercial value.

The Grey Men say they are paying for and managing time. However, they are con men. There is no Time Bank. The Grey Men turn our time into the grey cigars they constantly smoke in order to exist, and the more time that is stolen from us, the more the Grey Men proliferate.

Nevertheless, everything is a chimera. Momo is a fairy tale and just as true as Hans Christian Andersen's The Emperor's New Clothes. In Ende's novel, it is Momo who, finally, like in Andersen's fairy tale, reveals that "The King is naked" and thus makes people realize that saving time is a gigantic lie that has robbed them of life itself.

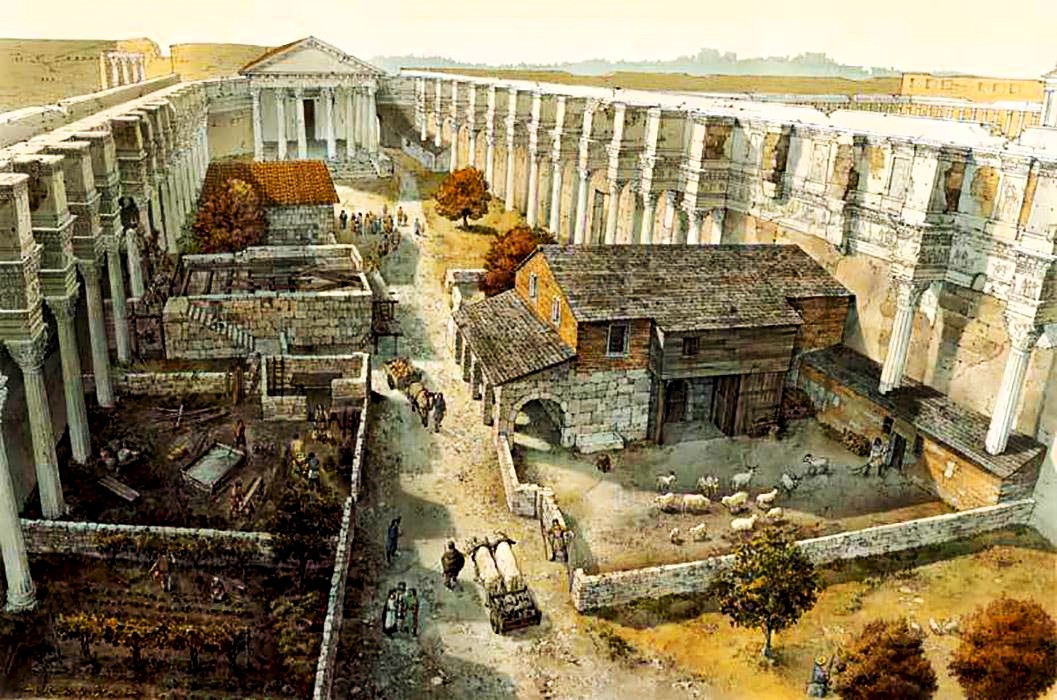

Momo is set in Italy and as I am walking home, I think that this country is the right place for such a fantastic story. Here in La città eterna, the Eternal City, people have during millennia come from all over the world and created a unique culture, so distinctive that it seems as if the entire city lives and breathes by and for itself. It as if it has turned itself into a giant organism. Here, buildings from different times have been built on top of and next to each other. If you during the night walk through the deserted places of Rome you will find that you are walking through and across time. Under your feet rest catacombs, temples and churches, and the miasma that has been gathered there rises up to the surface. The city tells you its stories and legends.

Time lives not only within us, but also outside of us. I realize it when I get home and step into a basement space that I have covered from floor to ceiling with my books. Some of them have already opened up themselves to me, others are waiting to do so. Down here rests the past, present and future.

In the world of books, I can travel back and forth in time. I also have the opportunity to return to books I have read (something I am currently engaged in) and then find that they, like me, have changed. On several occasions I have reread a book and found it to be quite different from when I first read it – either better or worse, or maybe simply ... different. I read somewhere that William Faulkner was once asked which three novels he had found to be the most fascinating. He replied "Anna Karenina, Anna Karenina, Anna Karenina". "But, it's the same book!" "I've read the novel three times and each time it was different."

Books are both frozen and living time. You ... my reader, you are right now in a different time dimension than I am, the one who is just now writing these lines. When you read my text, it is already written, aged. You are in my future and I am in your past.

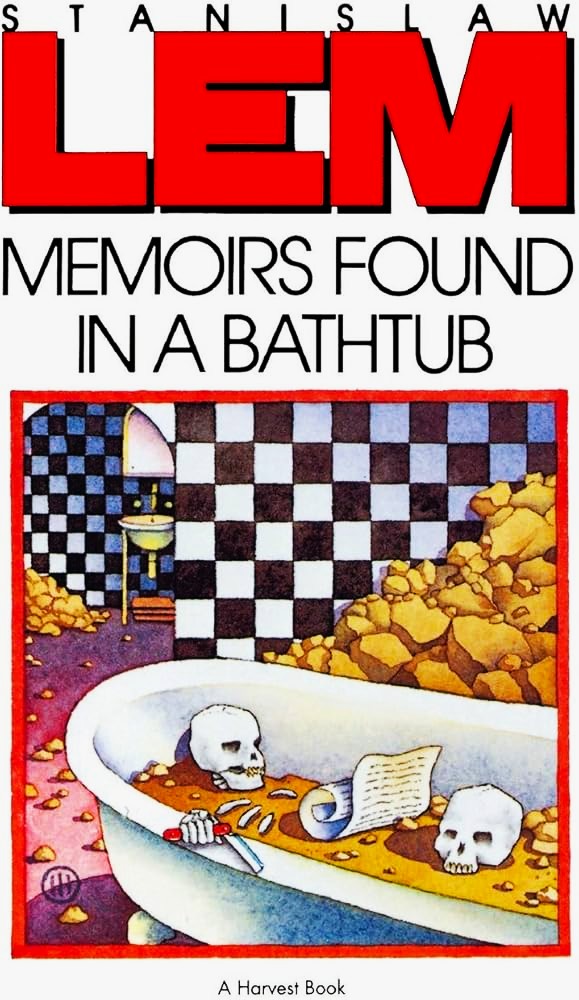

Reading a book about a bygone era makes me think of my youngest daughter, who is an archaeologist. Archaeologists visit times gone by. In one of his novels the subtle Polish science-fiction writer Stanislaw Lem combined books and archaeology. Memories found in a bathtub begins when future archaeologists have found a diary thirty centuries after it had been written. It is believed to be the only known trace of a human hand left on paper.

When they have, with the help of the sophisticated machinery which are at their disposal, succeeded in translating the ancient and forgotten text, it turns out that diary was written by the end of the twentieth century, i.e. some thirty years after Stanislaw Lem wrote his novel. The diary was written under a military dictatorship harassing its citizenry with an extremely complicated bureaucracy, during which although it had begun to use what the future archaeologists designated as "electronic brains", almost all vital information had been “papyr-based”

Like so many other novels set in a distant future, a catastrophe had taken place. In this particular case, it was a chemical chain reaction that caused an almost immediate worldwide decay of a material that had been

"whitish, flaccid, a derivative of cellulose, rolled out on cylinders and cut into rectangular sheets. This papyr was almost the sole means of recording knowledge and contained information of all kind, impressed on it by dark tint."

All papyr-based archives were wiped out. At that time, there was no mnetamnetism or technology that could crystallize information. Panic broke out when people lost their identity through the erasure of paper and were thrown into a state of complete anarchy, when all bureaucracy and construction activities collapsed and citizens abandoned decaying metropolises. A long period called The Chaos began when ignorance and superstition took hold of almost everyone.

Before the catastrophe had taken place, the nameless diary writer, who every night had written down what had happened to him during the day. This had been done in a desperate attempt to maintain his sanity. Just before the disaster took place, he had hidden his manuscript under a bathtub. Since the unknown writer lived under a ruthless military dictatorship, which tried to keep every citizen under its surveillance, the unknown secret service agent had been afraid that his diary writing would be revealed.

The young man had been given a secret mission. Everything within the huge Headquarters was secret, General Kashenblade had informed him:

Your mission. Conduct an on-site investigation. Verify. Search. Destroy. Incite. Inform. Over and out. On the nth day, nth hour, sector n, subsector n, meeting with N. Stop. Salary group under the cryptonym Bareback. Unlimited oxygen voucher. Payment by weight for redundancies and sporadic notifications. Report regularly. Your contact person is Pyra-LiP, your cover Lyra-PiP. In case you fall in battle, posthumous decoration with the Top-Secret Order, complete honour, salutes, memorial plaque and a written recommendation in your dossier. Any questions?

The poor recruit cannot obtain any clarity about what his mission really involves. Everything is secret. In his search, he is shovelled from one office to another, all with strange designations in the form of inscrutable abbreviations. Occasionally, he is presented with forms that must be filled in and handed over to secretaries who only act on orders from top managers and do not concern themselves with anything "below their competence".

The diary writer finds that that the best way to move between offices and different destinations is to slip in where doors are open and where you are not asked about anything. In this way, for example, he comes to the "library", buried down deep in the office labyrinth – a room cluttered with dusty, greyish volumes, densely arranged on sagging shelves. A bald, wind-eyed old man with a trailing gait shows him, under the few, naked light bulbs, one foul-smelling volume after another, while muttering "a splendid work . . . brilliant." As the young agent stumbles out of this "paranoid nightmare", he feels as if he has left a slaughterhouse.

The narrator in Lem's novel is a diary writer and a diary is undeniably a time machine that takes its reader back in time, and so are old letters, photographs, discoloured home movies, biographies and autobiographies.

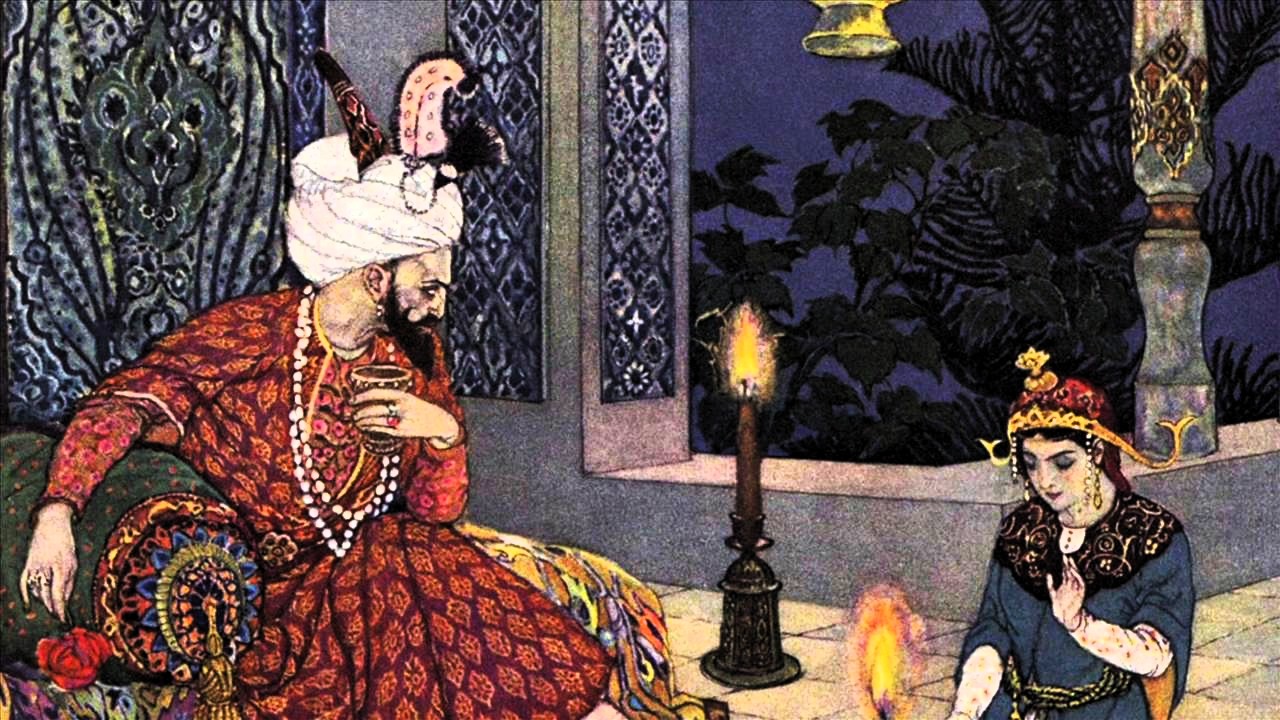

Several years ago, when I was studying literary history, I was told by one of the lecturers, Erland Lagerroth, that novels involve a process. I was annoyed by that assertion it was too banal for my taste. Maybe I misunderstood the whole thing, probably it meant that in a story one event follows another. And it can certainly be like that. The reader is wondering "and what happened next". That kind of wonder drives the stories forward and maintains the reader’s interest. It is easy to understand how the murderous king repeatedly postponed Scheherazade's execution in order to hear the continuation of the story she had not been able to finish when the day dawned. A Thousand and One Nights has certainly remained my favourite reading. It contains the entire fascination of storytelling, and with delight I often return to its stories.

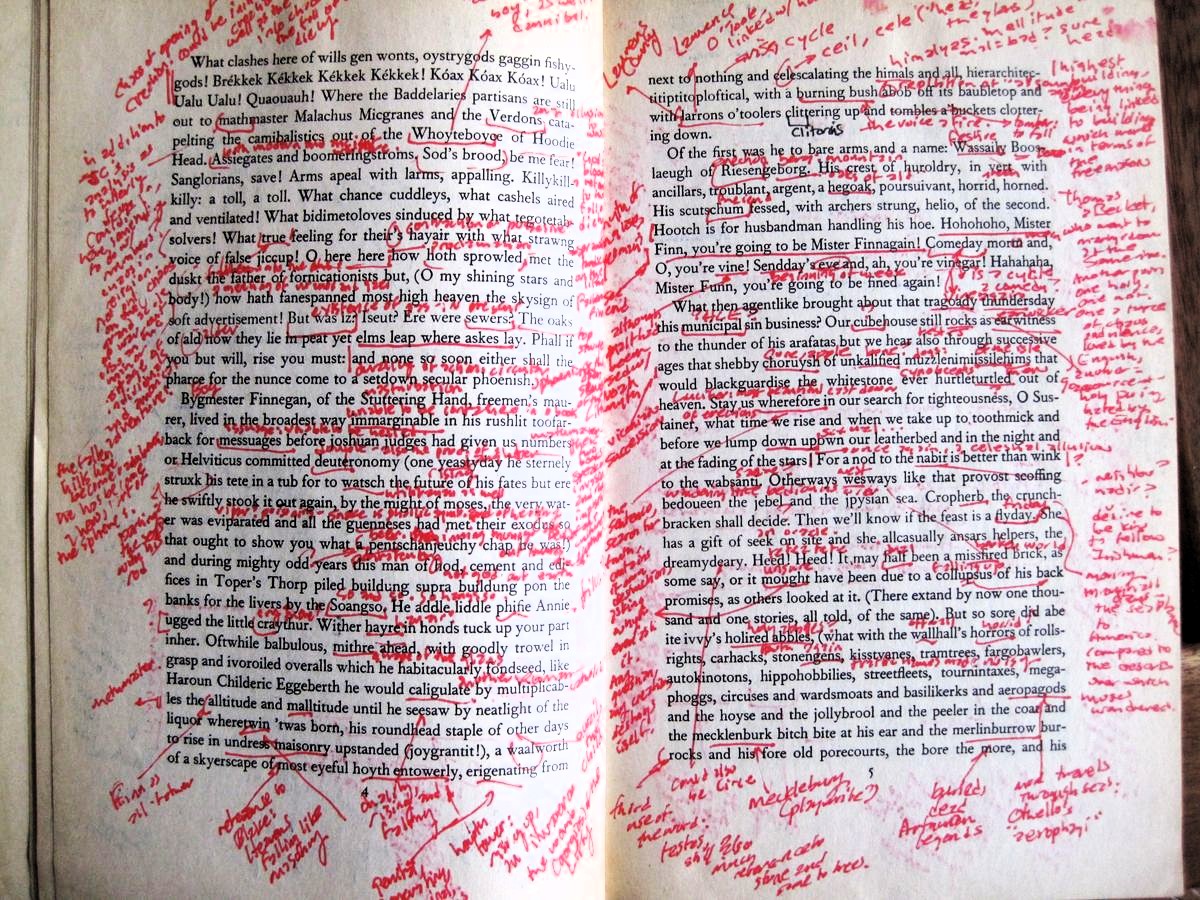

Books include their own time and an author is free to play with and manipulate the process of storytelling, but not to such an extent that the it becomes incomprehensible. An annoying example of this is James Joyce's Finnegan's Wake, which is incomprehensibly acclaimed by some connoisseurs. There have been times when I have tried to read it – a completely unnecessary effort. I could have spent my time better by reading other books worthy of the effort, than tormenting myself with that misery.

I remember how during my high school years I was fascinated by Lawrence Durrell's Alexandria Quartet, written between 1957 and 1960. The quartet's first three books depicted the same sequence of events, but from different points of view, which meant that the portrayal of the main characters in one novel shifted in such a way that they became secondary personalities in another. Based on the timespan depicted by the first three parts, the fourth part of the quartet moved the plot forward.

I recently reread Faulkner's Absalom! Absalom! from 1936 and found it even more complicated and stranger than Durrell's novels. Here the story emerged in a different manner. The narrator's voices are further complicated by the fact that they flow back and forth, while other voices come forward and recede, mixing together in a constantly changing landscape where even the resolution/final interpretation of the sequence of events becomes uncertain.

The reader senses the connections, but is forced to reconcile the different versions and voices without the author's help. However, it becomes abundantly clear that the historical depiction of a microcosm exposes the American South's dark legacy of racism, feelings of inferiority, shattered dreams of success, class thinking, slavery, and desperation, all within a framework of decay, violence, war and murder. A picture of a slice of time more than a process.

Absalom! Absalom! illustrates perfectly what the Italian Italo Calvino, a writer who also played with time and space, stated:

The time dimension has been shattered, we live and think in time The dimension of time has been shattered, we cannot love or think except in fragments of time each of which goes off along its own trajectory and immediately disappears. We can discover the continuity of time only in the novels of that period when time no longer seemed stopped and did not yet seem to have exploded, a period that lasted no more than a hundred years.

Calvino does not specify which hundred years he is alluding to. When they started and ended. He probably referred to the age of realist/naturalistic novels, as he had shown a great appreciation for what some writers had created before them – Homer, Ovid, One Thousand and One Nights, Ariosto, Cervantes, Cyrano de Bergerac, Defoe, Sterne, Diderot.

The quote above comes from the introduction to Calvino's novel If on a Winter’s Night a Traveller from 1979. A novel that dealt with the mystery of reading and dealt with the parallel worlds of novels and other stories. How an author like a magician can hide his tricks up his/her sleeves. In the first chapter, Calvino urges the reader to make him/herself comfortable, shut the door for the outside world to become immersed in the story that is about to begin:

In a small town a traveller sits on a winter night in a station bar. He has his suitcase next to him, maybe he is waiting for someone. In the chilly, smoke-filled room, he suspects the locals are critically examining him. Closing time is approaching and he is asked to leave the premises.

It now dawns on the reader that this is far from being an ordinary story. The author turns to him and reveals that there is an error in his book copy where the introductory section is followed by a story taking place in a Polish provincial household. The reader, who has now become part of the story, is forced to return to the bookstore to complain and then receives a new copy, while at the same time he is getting acquainted with Ludmilla, also known as the "Second Reader", thus a chaotic journey commences through literature and across the world. We are completely in the hands of the narrator, who provides us with ten chapters from ten different books, each and every one quite unlike the others, while we are taken different parts of the world and end up in unfamiliar, ancient and possibly fictional lands.

When the reader assumes s/he has got some kind of grip on the text, s/he is forced back from the bookstore to the publisher, from the publisher to a university professor, who turns out to be an expert in literature from an extremely small language area. The versatility is almost incalculable, we have ended up in Kathasaritsagara, a Sanskrit word that means something like "The ocean into which the rivers of stories flow".

Italo Calvino was a member of Oulipo, Ouvroir de littérature potentielle, roughly translated as Workshop for Conceivable Literature. A loosely organized association with mainly French-speaking members, though also with corresponding Latin Americans, English, Scandinavians, Italians, etc. Particularly prominent at the movement’s pinnacle were the novelists Raymond Queneau, Georges Perec and Italo Calvino, but also several poets and not least mathematicians have been and are outstanding members. Oulipo still exists.

Within Oulipo, people gathered around literary games in which, with the help of rebuses, mathematical problems, the exclusion of a certain letter, card games, drawings, and a variety of other methods, they searched for new structures and patterns that could be used by writers "in whatever way they thought suited them". Queneau described the Oulipians as "rats who construct the labyrinth from which they planned to escape."

The playfulness of the Oulipians can sometimes be quite fun and stimulating, sometimes a somewhat too cryptically strained, although one of their rules is to avoid incomprehensibility. The writings of several earlier, distinctive writers such as Swift, Rabelais, Lewis, Carroll, Raymond Roussel, Homer, Jorge Luis Borges, Erik Satie, Alfred Jarry, and even authors of sacred writings such as the Bible, are with Oulipian admiration characterized as plagiat anticipé, anticipatory plagiarism.

I stayed in the basement and put on a CD (I also keep a lot of CDs and DVDs down there) on which the violin virtuoso Nigel Kennedy together with the Polish Yiddish trio Kroke Band played Time 4 Time, which introduce a trotting rhythm over which a painfully sentimental gypsy violin floats and languishingly sweeps forward, all the time with the roaming beat beneath it, as if to conjure up a vision of a gypsy caravan moving across the puszta. The timeless rhythm of nomadic peoples traveling across Asian steppes or African deserts, above which a star-studded firmament arches and tells them about time and travel direction. Finally, the CD explodes in Kukush, a loose, unbridled extravaganza, but with an unfailing, underlying and captivating rhythm beneath Nigel Kennedy who on his electric violin approaches a Jimi Hendrixesque improvisational ecstasy.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e33gPMdasVE

Music as living time; intangible, instantaneous, captivating and yet bound within a fixed set of rules, which in spite of their strict framework provide seemingly endless possibilities for improvisation. However, every misstep might give rise to fatal dissonance, as when mathematical formulas collapse through minor miscalculations.

In addition, music is timeless. I can, whenever I feel like it, put on a CD with music by of Palestrina, Bach, Schönberg, or Vivaldi. It was different in the past – when, provided you belonged to the wealthy classes, could only enjoy a Beethoven symphony once in a lifetime. Music is for me as inexplicable as quantum mechanics.

At the end of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, which I have difficulties with understanding, Ludwig Wittgenstein wrote the well-known phrase "Of which one cannot speak, one must remain silent". For most of its readers, this has meant that problems connected with ethics, the meaning of life, human existence, and other metaphysics, lie beyond the boundaries of language and therefore cannot be expressed through words, logic, or other factually based knowledge.

But... since Wittgenstein nevertheless approached metaphysics by a variety of means, one might interpret his quoted statement as referring to certain aspects of reality that are ineffable since our language is far too limited and thus insufficient. It locks us into predetermined, paralyzing ways of thinking, and within such a difficult conundrum we find a concept like "Time".

So... Maybe I should keep quiet when I try to express my thoughts about the time. But still, I use my writing mostly for myself. What does it matter if I am wrong while moving in metaphysical areas? First of all, för me it is a pleasure to write and I also use my writing to capture and try to find out something about my often swirling thoughts.

I ask myself what the three dimensions – length, width, height – would be without the influence of time – if not stagnant and dead? It is time that gives them life. Time drives the dimensions to the right or left, up and down, in and out, back and forth. It has been written and said that time does not exist in itself, only in relation to events or objects that already have been set in motion. But? Would they have been on the move without the time? I don't know. I'm not a physicist. Mathematics has always been a closed space for me. I've tried, but never found the keys to it.

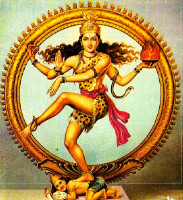

However, I have learned that Hindu philosophy equates movement with life. Life and movement arise through karma, which briefly might be said to equal the law of cause and effect. If karma ceases to work, time is transformed into eternity—it becomes dormant in itself. But before that, Saṃsāra prevails – the cycle of existence, the ticking circle of life, manifested in Shiva's cosmic dance that simultaneously creates and destroys.

.jpg)

Shiva Nataraja, the Lord of Dance, expresses through his violent performance creation and destruction, prerequisite for life, but also its balance, protection and preservation.

With his long hair swaying in the frantic tempo of the dance, Shiva accompanies himself with a drum that he holds in his right hand; the rhythm of life, the beating of the heart, the pulse of life, the eternal cycle. In his left hand burns the fire of destruction – no life without death. But, Shiva has four hands. The third he raises in a sign of peace, with its palm open to the viewer Shiva seems to say: "Be calm, I move. I live, you shall all live." His fourth hand is directed at his raised leg – "I move, life goes on and I watch over you. I who am one with the All; man and woman, day and night, the time that incessantly moves us on.

Everything is in balance; Shiva's dance may be excited and seemingly unbridled. Not at all – it moves within a fixed framework, the cosmic rules. He steps on the god Apasmara, a child with a moustache, the demon of ignorance, whose pathetic knife is ignored by the dancing World Ruler who keeps his gaze fixed upon us: “Don’t you realize that I am identical with the absolute balance of Universe? Everything is indeed moving; time, atoms, planets, galaxies. Through my cosmic dance everything is held in place, time binds chaos, everything is in balance, the energy is constant, although changeable, it moves within the given framework of the Cosmos.”

Time is thus linked to movement. Something that I experienced when I in my youth worked as waiter on the trains between (mainly) Malmö and Stockholm. A journey that took between five and seven hours. However, the movements of the trains meant that the working day did not feel like it was measured through some abstract time, linked to the circular movement of the hands over a dial, Instead, the passage of time corresponded to geographical stretches – Malmö-Hässleholm, Hässleholm-Växjö, Växjö-Nässjö, etc. By looking out the window, I got an idea of the passage of time.

I would think that a peasant used to consider time as a movement between dawn and dusk, between spring and winter, reflected by the sun's journey across the sky. The time used to be something different from what it is now. Authorities tried in their own way to discipline people's consciousness of time, first with church bells, then with the help of factory whistles (time is money) and over time through increasingly sophisticated methods, from punch clocks onwards.

But where does time lead us? As new findings come to light, science becomes more and more complicated and hopelessly incomprehensible to an amateur like me. Perhaps this is what Nobel Prize winner Richard Feynman meant by stating that the ideas born through quantum/electrodynamic discoveries cannot be perfect. They are rather models and thus not identical to "reality", which continues to be beyond human comprehension and perhaps will continue to be so.

Einstein considered "time" and "space" to be concepts we use for our thinking, for the development of a reasonable theory. Theories that to some extent might be mathematically and experimentally proven, but that does not mean that mathematically conditioned models govern our way of living and perceiving the reality that surrounds us. Quantum mechanics tells us that the exact position and state of particles can never be completely known, uncertainties are and remain an integral part of Creation. Nevertheless, scientific discoveries point to a direction, and might describe a physical reality that over time will become increasingly sharp and thus change the lives of all of us.

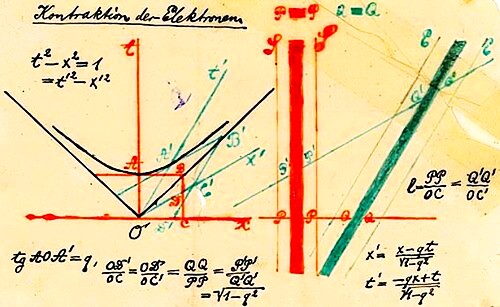

An influential mathematical model is the so-called spacetime, which combines space and time into a single interwoven state, a continuum, i.e. something that has a spread in space and which in theory can be divided into infinitesimal parts. It was Hermann Minkowski, who had been Einstein's mathematics teacher during his time in Zurich, who created the concept of spacetime as an attempt to support Einstein's theories.

Einstein and Minkowski shared a desire to use abstract mathematics as a means to describe and possibly transform our perception of the nature of the Universe. They have succeeded to the extent that their mathematical models now have been refined and also largely experimentally proven. However, question marks remain, one is whether mathematicians like Minkowski and Einstein really believed that we live within a space-time with all that would imply for our everyday existence, for our perception of time, for our faith. Einstein also had his doubts about the applicability of Minkowski's mathematical models. He called them überflüssige Gelehrsamkeit, superfluous learning.

When Einstein's close friend, the engineer Michele Besso, died, he wrote a letter of condolence to the deceased friend's family. Ever since they had studied together at the Zurich Polytechnic Institute, Einstein and Besso had been close. Besso was not only Einstein's friend, but was also an understanding man with whom he could openly and on a completely different level from what he did his fellow scientists discuss both life issues and science. Einstein wrote:

Now he has preceded me a little in parting from this strange world, too. This means nothing. For us believing physicists the distinction between past, present, and future only has the meaning of an illusion, though a persistent one.

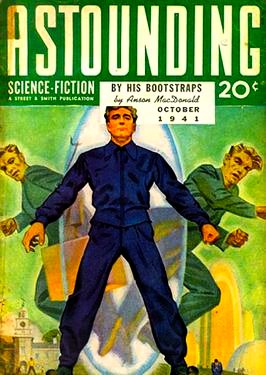

I don't understand much of all these scientific theories about the relationship between space and time, my ignorance makes me think of the science fiction author Robert Heinlein's short story By his Bootstraps , whose main character.

had as much chance of understanding such problems as a collie's perception of how dog food ended up in cans.

However – a growing confusion and uncertainty leads to revisits to things that are still considered self-evident, for both the common man and scientists. For example, that time moves inexorably forward. It cannot be reversed, something that has led several scientists to speak of the "arrow of time".

Where time moves is however an unsolved riddle, one seems to indicate that the speed of the "time arrow" is changing, it is assumed that it is slowing down and that all of the Creation is moving towards Entropy. Matter changes, falls apart; metal rusts, rocks wear down, organisms age and rot away, stars and galaxies die. The energy is certainly constant and indestructible, but it can be dispersed into smaller components. And then?

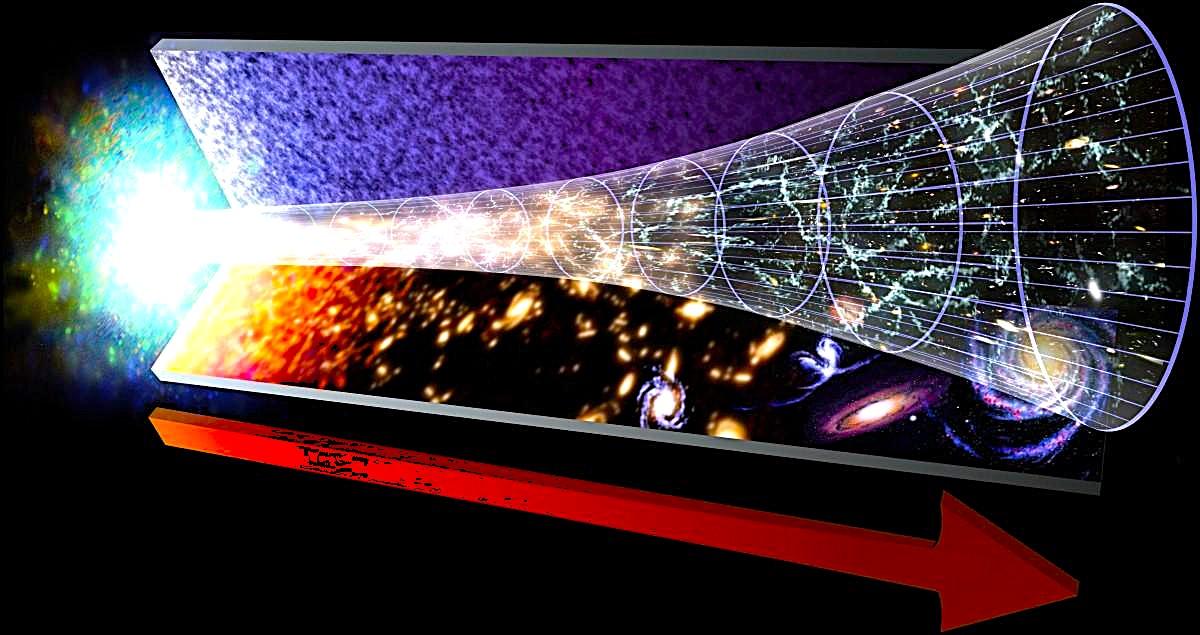

Several Hindu philosophers imagined the Universe/Brahma, as a vast organism that breathes; inside out. Scientists assumes that the Universe was once born – The Big Bang, when particles from an exploding centre were thrown in all directions crating a Universe that demonstrably still moves outwards from a core, until the movement eventually slows down.

For some Hindus, it is obvious that every tiny part of the Cosmos is part of this vast spectacle. The Maitrayaniya Upanishads, possibly finding its origin around 500 f.Kr, stated:

There are certainly two forms of Brahman: Time and Timelessness. That which precedes the Sun is Timelessness, perfect and indivisible. But what started with the Sun is Time, and it can be divided.

Brahman can then be considered timeless – eternal. This while earthly life is dependent on the sun and thus associated with man's concept of time; day follows night, the passage of months, the changing of the seasons, are all phenomena connected with time in its form of motion. The universe also moves, but it is a different form of movement – more like exhaling and inhaling, heartbeats. The cosmos is by Hindu philosophy likened to purusha and is then described as having a human shape. Human beings are like mirror representations of the cosmic purusha, though subjects to a different time than this enormous assembly. We humans are slaves to the time of the sun, while he time of the universe is the breath of Brahman.

What happens to matter and time when entropy finally strikes and the outward movement of the Universe slows down and ceases? Where does it all go? Perhaps it falls back to its origins, to a point that then becomes so compact, so bursting of compacted mater that it cannot hold all its parts together. The result – a new Big Bang. An endless pulse movement – Brahman breathes. Again – what do I know? I am not a scientist, not a physicist, no logician. I cannot even count, only the most basic algebra.

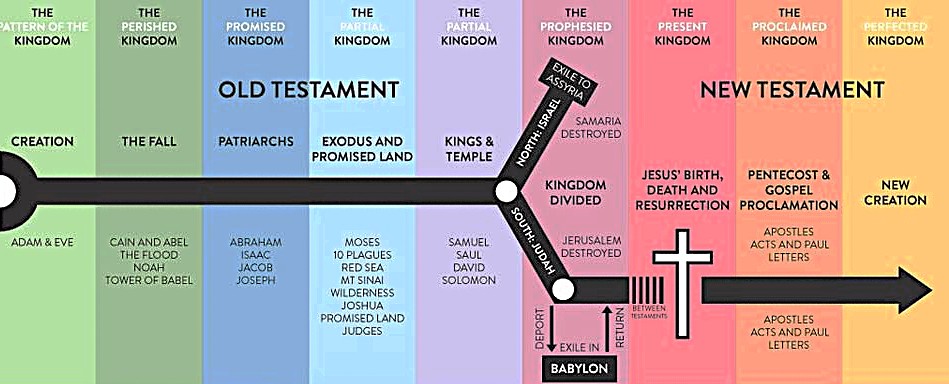

Sophisticated Eastern philosophy, such as what has thrived within Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism, tends to be more cyclical than the tradition inspired by Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. These so-called Abrahamic religions have a more linear concept of time, with a beginning and an end. A way of thinking that easily leads to a progressive view of existence, that one thing leads to another, but not as in the concept of karma in a cyclical movement, but towards an end goal, happy or unhappy depending on which individual you are born to be.

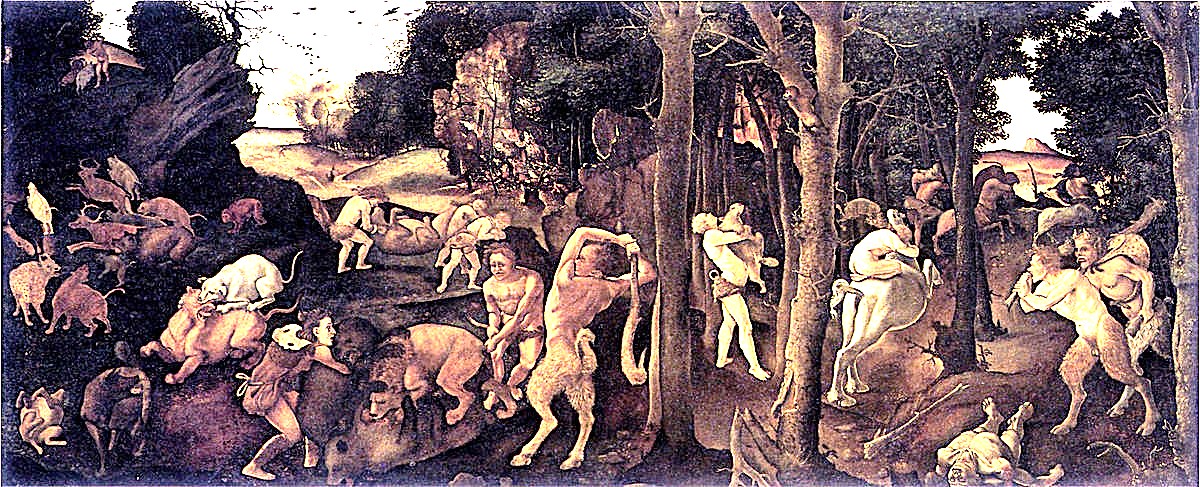

Virtually all ancient Greek philosophers believed in development in the sense of "progress" as improvement. In other words, a temporal movement towards what was perceived as a more refined, improved and universally desired stage of well-being. True, just as nowadays, it was written nostalgically about the fact that there had once been better times – a golden age when people were happier, just as Jews and Christians could imagine a perfect Garden of Eden. The Jews and Christians wrote that human's sin drove them out of this Paradise, while the ancient Greeks seem to have considered it to have been man's arrogance, a belief in his own great ability, hubris, that caused him to leave an original state of innocence and simplicity.

The Greeks, however, seem to have perceived this "golden age" not only as a glorious time, but also as a somewhat brutal time, in the absence of many of the comforts available to the Greeks in their present day – a "civilized" existence.

There were setbacks – war and plagues – but as the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius wrote, we are moving pedetemtim progredientes, step by step, towards a better future, a concept that in English has become progressive time. It seems that most cultures, whether they have a cyclical, or a progressive perception of time, have their own cultural heroes. That is, mythological heroes, or sometimes even godlike figures, who through discoveries and inventions managed to change the world for the better, often against the will of the gods because these believed that preserving the status quo benefited their power.

A cultural hero/heroine could, for example, have brought fire to people, taught them agriculture and cattle husbandry, given them songs, dance and other cultural expressions, created new traditions, instituted laws and religious practices, etc. It seems that almost every known cultural circle has had one or more cultural heroes. They are not always people; they could also be talking animals. To show how common they are, I can mention a small number of those cultural heroes that exist among different peoples.

The Greeks had their Prometheus, Aztecs Quetzalcoatl, West African Ashanti – Anansi, Irish Celts – Cú Chulainn, Australian Aboriginals – Bunjil, Chinese – Fuxi, Finns – Ilmarinen, Inuit – Apanuugak, Lakota Sioux – Iktomi, Sumerians – Gilgamesh, Polynesians – Maiu, Tibetans – Gesar, etc., etc.

In Western ideology and politics, the idea of progress has become almost exclusive. For individuals it is important to become successful and success is then generally measured in money. High incomes give respect, a successful career is when you are considered to be better than others, higher positions give better income and even luck in business is considered to be a success and a sign that you have managed your time on earth in an exemplary way.

But even a society must be successful and how far a country has come on the step scale is mainly measured in GDP, a measure also primarily based on economic progress. Gross domestic product is expressed as the value of a country's total consumption of goods and services, investments and exports over the period of one year.

The concept of progress was introduced into the social theories by early 19th century, especially in the context of social development described by philosophers such as Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer. At the same time, there was talk of modernization, which meant that society should remove traditional barriers to free markets. Accumulation of wealth meant that one had to be aware of the opportunities that existed to enrich oneself and seize the opportunity as soon as possible, time became an increasingly important factor in such social systems.

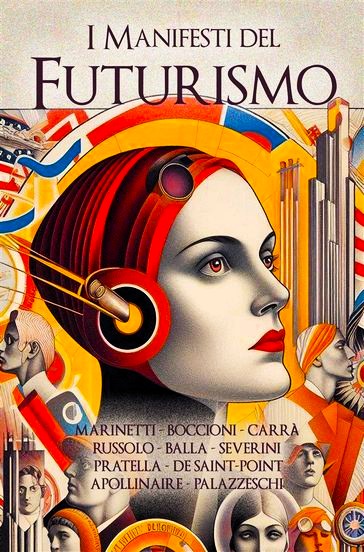

Bold, quick decisions were celebrated while the pace of existence increased, freed from nature, religion and traditions. The Futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti captured the spirit of the times in his manifesto from 1909, Time was turned up to a feverish heat, but in a "positive" sense:

1. We intend to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness.

2. Courage, audacity, and revolt will be essential elements of our poetry.

3. Up to now literature has exalted a pensive immobility, ecstasy, and sleep. We intend to exalt aggressive action, a feverish insomnia, the racer’s stride, the mortal leap, the punch and the slap.

4. We affirm that the world’s magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car whose hood is adorned with great pipes, like serpents of explosive breath—a roaring car that seems to ride on grapeshot is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

5. We want to hymn the man at the wheel, who hurls the lance of his spirit across the Earth, along the circle of its orbit.

6. The poet must spend himself with ardour, splendour, and generosity, to swell the enthusiastic fervour of the primordial elements.

7. Except in struggle, there is no more beauty. No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece. Poetry must be conceived as a violent attack on unknown forces, to reduce and prostrate them before man.

8. We stand on the last promontory of the centuries!… Why should we look back, when what we want is to break down the mysterious doors of the Impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, because we have created eternal, omnipresent speed.

9. We will glorify war—the world’s only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman.

10. We will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind, will fight moralism, feminism, every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice.

Change and worship of progress were far from new in Western culture. Although at the end of the 1800s it was linked to the pace of time, the rapid pounding of train wheels against the rails, raising smoke from factory chimneys, their blistering hot furnaces and powerful steam hammers, the increasingly common automobiles and aircraft. A paroxysm that found its explosive peak in the First World War, with its devastating, mechanized carnage.

It was not only the freedom of thought and the exchange of knowledge that was embodied in Gutenberg's revolution of the art of printing, but in parallel with this intellectual development, increasingly deadly weapons, were created leading to the progressive society we now live in.

Sociologist Robert Nisbet stated that "for three thousand years, in Western civilization, no single idea has been more important than the notion of progress." An important part of this perception has been an overestimation of the sovereign value of one's own culture compared to traditions of other countries and peoples. Added to this was a boundless reverence for economic and technological growth, coupled with a belief in scientific/academic knowledge.

An attitude that was reinforced by Darwin's theory of evolution, which was interpreted in conjunction with man as the "crown of creation", the end goal in all development and above it all towered not Homo sapiens, the thinking man, but Homo economicus, the economically minded man who over time had developed into the master of the Earth, far superior to his primitive fellow human beings.

The word "primitive" comes from the Latin primitivus, and has come to denote the first of its kind, and when the term is related to human society, it describes an early stage of development where people live in a simple manner without machines and sophisticated writing systems. Nowadays, the word "primitive" has come to be replaced by "underdeveloped", a term that also implies a form of progressive thinking, although the word "development" rather means "open up". Of course, one may wonder whether the exploitation of our natural resources and the development of sophisticated weapons of mass destruction can really be described as “progress.

Jewish religion does not seem to have been particularly obsessed with any idea of progress, but there was a strong belief that God was the Lord of Time and that He worked in history by punishing and rewarding His people. In times of persecution, the idea might thus arise that God, after punishing people for their mistakes, would also reward those who had been steadfast in their faith in Him. At the same time, God would punish the enemies of the righteous.

By the time of Jesus' birth there had among the Jewish Essenes developed the belief in an approaching Apocalypse, Revelation, and Judgement Day. The Essenes, due to Roman occupation and Jewish complicity isolated the themselves in the desert area of Qumran, where they lived a pure, strict monastic life awaiting God's doom. Several of their writings were found between 1947 and 1956.

However, the absolute culmination of a temporal view of human development came through Christianity, as it developed after the death of Jesus. Here we find the Jewish idea of man's arrogance and faith in his own ability that made God to cast out the first human couple from their eternally innocent bliss in Paradise. Humans became compelled to administer the earth through hard work. To lead them onto the right path, God gave them a set of rules to live by. He punished and rewarded humanity throughout the course of history. From time to time, God sent His prophets to enlighten people about the unfortunate consequences of not obeying His commandments.

Christianity's contribution to this development was that God, apparently resigned after his constant attempts to reform his creation and finally felt compelled to incarnate himself as a human being and in the form of Jesus become a tangible example of how one should live. However, even this attempt went badly – the ungrateful people killed him.

Now, according to many Christians, nothing remained but the Last Judgment, when all mankind would be held accountable for their misdeeds. The righteous would be saved by the establishment of a new glorious world, while the guilty ones would be punished with eternal torment. An idea that was also adopted by Islam.

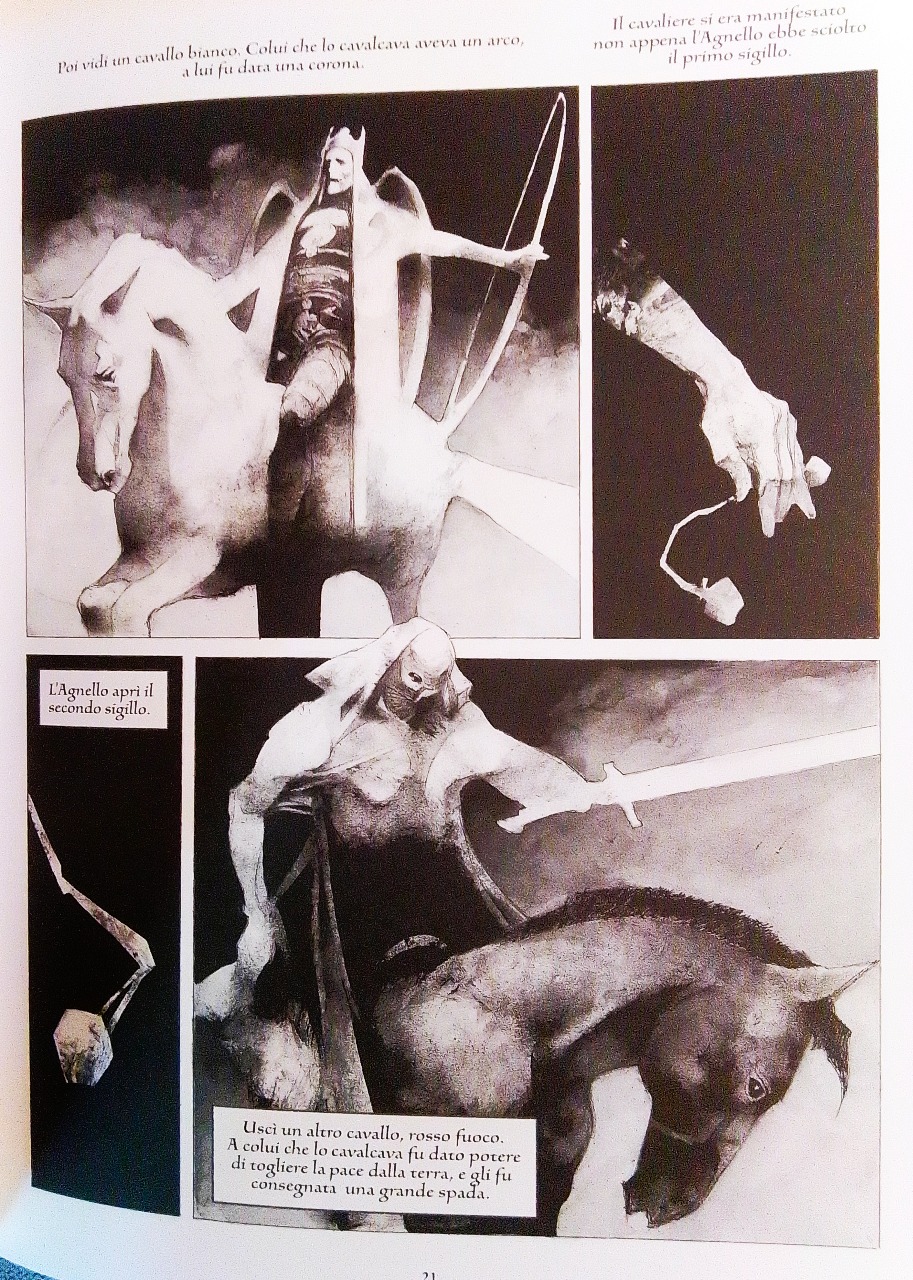

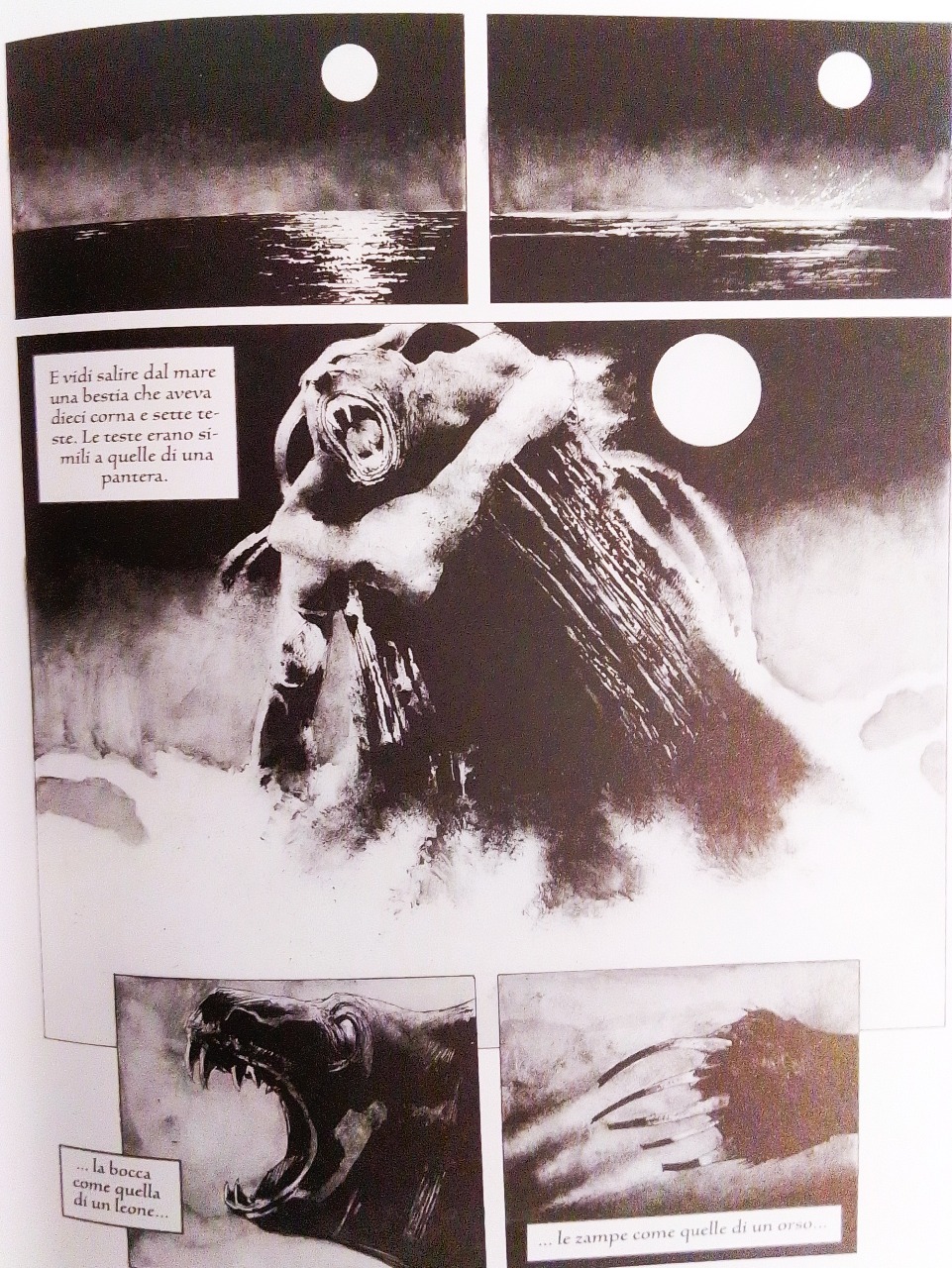

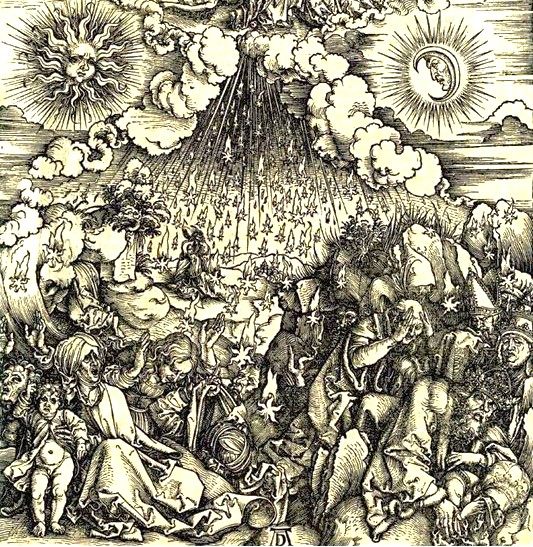

John' s Terrible Revelation is the last book of the Bible. Doomsday prophets and fanatics seem to love this book in which the forgiving and love-preaching Jesus has been transformed into an avenging violent persecutor and uninhibited tormentor who, in an apparently insane desire for revenge, hurls millions of people into merciless suffering and eternal damnation.

The book was probably written in the eighties AD by a certain John, a Christian-Jewish exile who had been forced to the live on the island of Patmos, off the present-day Turkish west coast. In bitter schadenfreude, John indulges in visions of all the evil that will befall enemies to his faith and how God after He has wiped them out from the face of the earth will establish a glorious Kingdom of Heaven for righteous and steadfast believers like John and his ilk. It is evident that John's revelry in all the misery that will befall the wicked alludes to conditions that prevailed in his time. The historian of religion Elaine Pagels has, through past and present literature, carefully analysed John's gloomy, admittedly powerful, but to put it mildly nasty visions.

John not only turned against his oppressive Roman overlords who had destroyed the Jewish temple and razed Jerusalem to the ground, but he also raved against Christians who had abandoned the Jewish faith and joined St. Paul in his submission to Roman authority and rejection of certain aspects of the Mosaic Law.

From early on, there were a number of Christian prelates who opposed an acceptance of John's violent visions (there were at the time a number of other visionaries who, like John, claimed that their visions had at least the same authority as the Gospels).

Eusebius (260-339), bishop of Caesarea in what was then Palestine, wrote an extensive church history in which he quoted a number of writings. Eusebius was a scholar who relied more on books than anything else. There are few anecdotes and no humour in his rather dry book, which in return is rich in quotes and interesting excerpts from various older writings. Among other things, Eusebius reproduces letters and writings by the by him much admired Bishop Dionysus of Alexandra, who had about as if the Revelation of John had stated that

some of our predecessors rejected the book and pulled it entirely to pieces, criticizing it chapter by chapter, pronouncing it unintelligible and illogical and the title false. They say it is not John’s and it is not a revelation at all, since it is heavily veiled but a thick curtain of incomprehensibility so far from being one of the apostles, the author of the book was not even one of the saints, or a member of the Church but Cerinthus, the founder of a sect called Cerinthian after him, who wished to attach a name commanding respect to his own creation.

Bishop Dionysus, however, did not want to completely dismiss the Revelation of John because "many good Christians have a very high appreciation for it." However, he could not refrain from divulging his doubts that it was Jesus' disciple John who had written the book, as several of his more fanatical contemporaries had claimed. Dionysus, who was a learned man and had Greek as his mother tongue, believed that the Gospel of John was written with

A remarkable skill as regards diction, logical thought, and orderly expression. It is impossible to find one barbarous word or solecism, or any kind of vulgarism. For, by the grace of Lord, it seems their author possessed both things, the gift of knowledge and the gift of speech.

It was worse with the author of the Book of Revelation, whose "language and style are not really Greek: he uses barbarous idioms, and is sometimes guilty of solecisms."

That the Book of Revelation finally found a place in the Christian canon and even ended up as the effective end of the entire Christian Bible is primarily due to the efforts of Bishop Athanasius (296-373). For forty years he was a dominant voice within Christendom, several times banished from and returning to his bishopric, he was a combative and skilled theologian, as well as a smart and power-hungry politician.

Athanasius early on found that if the Book of Revelation could be established as a canonical scripture, revealing the future and final judgment that God intended for the peoples of the earth, it could by him be used to condemn his adversaries, especially those who occasionally succeeded in usurping the bishopric from him and who, unlike Athanasius, claimed that Jesus Christ was not identical with God but "consubstantially" equal to God. It might seem to be a subtle difference, but these different perceptions divinity could result in violent riots with fatal outcomes. Supported by the Book of Revelation, Athanasius was able to equate his adversaries, the Arians, with those deniers of God’s real nature who according to the visions of John were going to be subjected to a multitude of horrors and mass destruction.

A trick that has since has been used by Protestants to condemn Catholics, and by Catholics to condemn Protestants, and on almost countless occasions when the Apocalypse of John has been used to predict God's destruction of countless opponents and other tumultuous events such as the HIV/AIDS and COVID epidemics, as well as a variety of wars. Not to mention how the "Sign of the Beast" – 666 – has been applied to Satan, a host of popes, Nero, Domitian, Vespasian, Muhammad, Napoleon, Hitler, Stalin, Reagan, Gorbachev, Jimmy Carter, and Saddam Hussein, to name only a few of them. Strangely enough, there are millions who still believe in the Book of Revelation and that it predicts the future in detail, even though it is perfectly clear that the Apocalypse was written in its time and for its time.

The Revelation of John thus has to do with time – the future and John's visionary visits to God during the Last Judgment can thus be regarded as a form of time travel. Many people have through their visions travelled into the future, although a few have also visited the past.

Some reached another time through dreams or sleep, as in the legend of the seven sleepers in Ephesus who fell asleep during the Roman persecution of Christians and then woke up when the whole world had become Christian (a legend that also appears in the Quran), or Rip van Winkle who fell asleep in the Catskill Mountains when the future United States was English and woke up 20 years later when it had become its own nation.

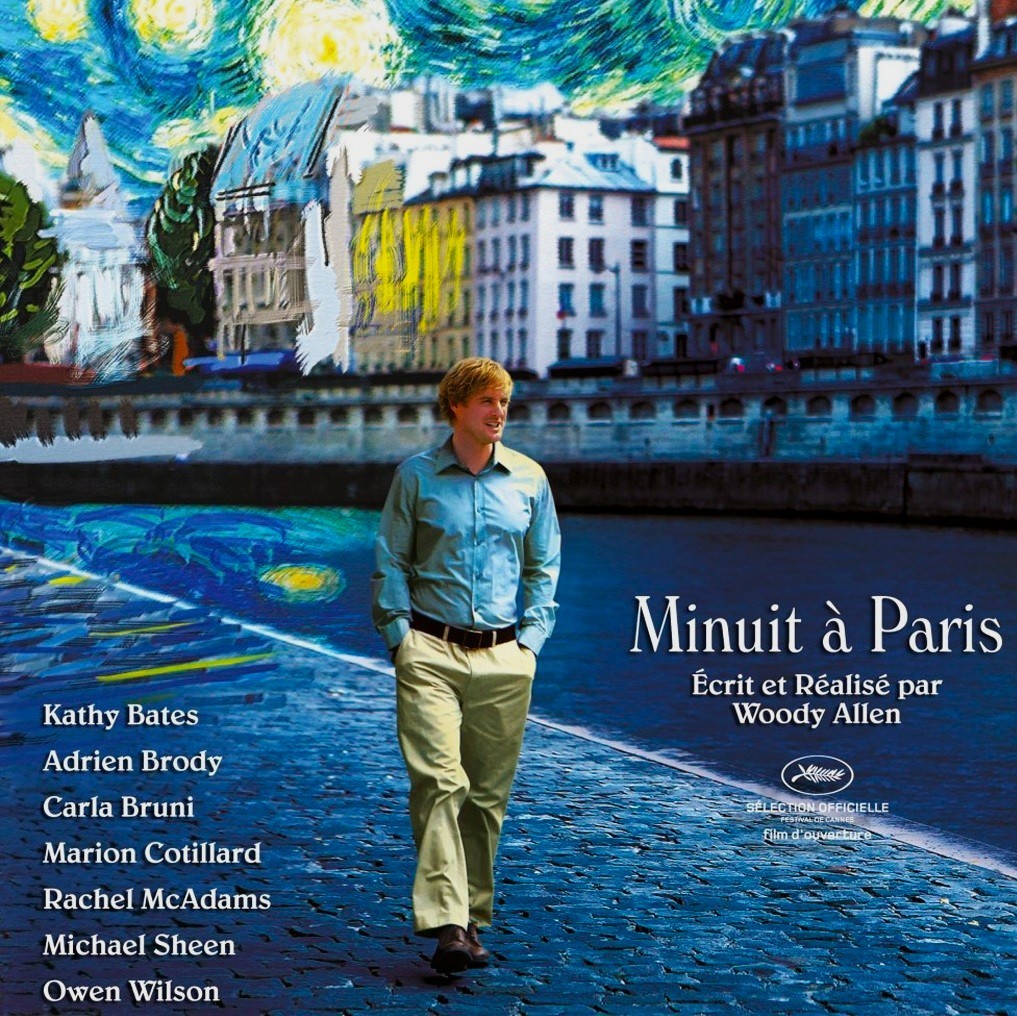

Another variant is the play The Bed Bug, a play from 1929 by Mayakovsky, in which a worker is frozen for fifty years and thawed in 1979 when he is shown in a communist Utopia in a zoo as an example of bourgeois habits from anno dazumal. A similar time travel was presented in Woody Allen’s film Sleeper in which Miles Monroe, owner of the Happy Carrot Health-food Store in New York, is frozen in 1973 and thawed in 2173.

Then there are a number of fairy tales that tell of other time dimensions, such as when the Japanese fisherman Urashima Tarō ended up in an underwater palace in which he believes he had stayed for three days, only to find on his return to earth that he had been gone for decades without having aged, something that also happened to Tannhäuser after living in the Cave of Venus, as well as similar experiences by other heroes and heroines who had ended up in parallel worlds together with fairies and trolls. There are several such parallel worlds where time follows different rules than those that prevail in ours, such as the Celtic Tír na nÓg, the Tibetan Shambhala, or the Chinese Kunlun.

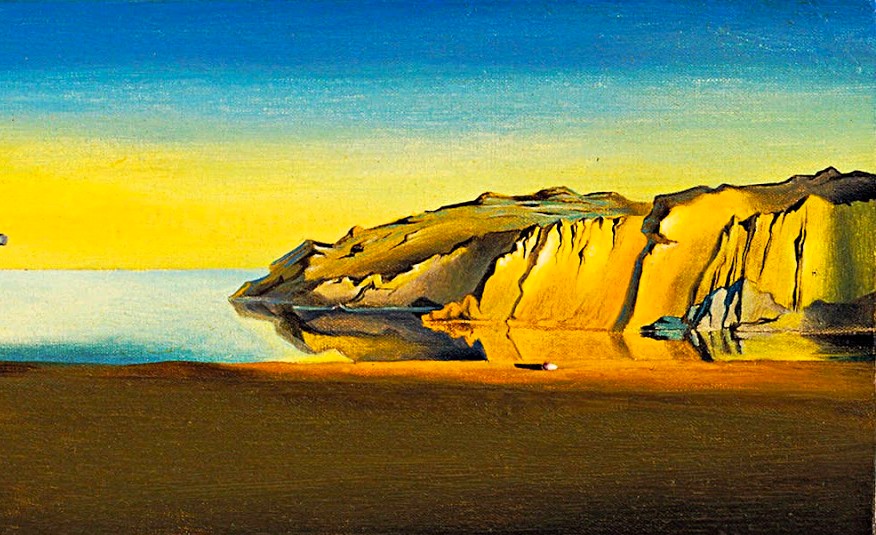

.jpg)

Other fairytale characters experience their future in dreams such as Scrooge in Dickens' Christmas Carol, or Julian West in Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward.

You can also be taken back in time, as in Hans Christian Andersen's The Galoshes of Fortune, which takes their wearer back to King Hans' time in the early fourteenth century, or Mark Twain's A Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur's Court, where engineer Hank Morgan wakes up in a field outside King Arthur's castle, after a blow to the skull with a crowbar. Confused, he asks "Bridgeport?", to which he gets the answer "Camelot".

.jpg)

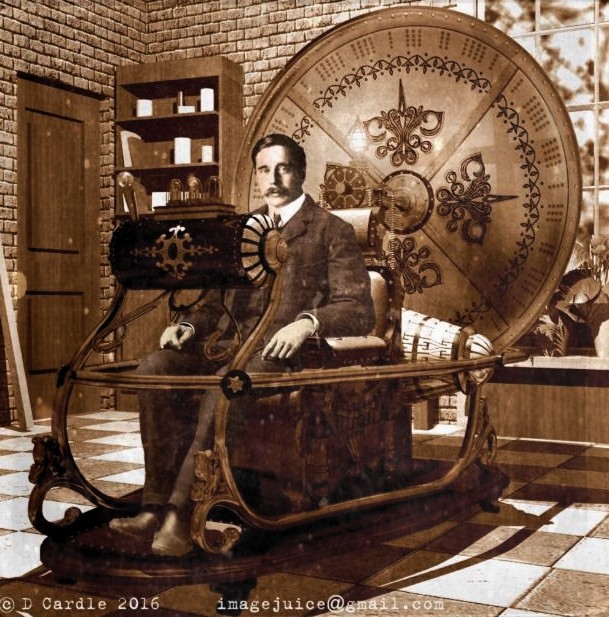

But it wasn't until 1895, in King Edward's England, when a time traveller climbed on his strange, bicycle/sleigh-like time machine that time travel took on a whole new aspect. It retained its adventurous fascination, but now the whole scenario was changed through new technology, scientific speculation and social criticism and thus time travel became a source of increasingly complex reflections on the special and incomprehensible nature of the time. A number of science fiction writers have since followed in Wells' footsteps and his story has spawned at least four films, all of which were quite unsuccessful.

Wells' story, like so many of his short stories and science fiction novels, is both exciting and thought-stimulating. The time traveller voyages all the way to the year 802,701, where he encounters the Eloi – small, naïve and humanoid creatures living in modest communities among the ruins of huge, dilapidated buildings. Cheerful and carefree, Eloi fears dark, moonless nights. After exploring the area around the Eloi settlements, the time traveller reaches the top of a hill overlooking what he believes was once London and realizes that nature has now taken over the entire planet Earth and that humans have returned to their origins as small vegetable-eating creatures.

Later, he encounters the Morlocks, ape-like troglodytes living in the darkness underground and only coming to the surface during moonless nights. The time traveller realizes that Morlocks control and feed on the Eloi and speculates that humanity eventually had been split into two different species. The privileged aristocracy of his time has become the Eloi and the enslaved working force have evolved into Morlocks.

The story contains both love and suspense, before the time traveller travels further into a foggy future. Devid of human life it seems to anticipate T. S. Eliot's The Hollow Men:

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper.

The time traveller manages to return to his own Edwardian time, but later disappears without a trace. However, that did not mean he vanished from literature and fantasy. Almost at the same time as The Time Machine was published, the new natural science broke through. Previously, matter and energy had been studied based on what scientists such as Isaac Newton and James Clerk Maxwell could calculate and observe within their traditional, but limited laboratory environments. This so-called classical physics had described the movements of bodies under the influence of various forces.

However, this previously applicable and often efficient "classical physics" were eventually challenged and changed by the study of matter and energy at very high speeds and/or at very large or extremely small scales. The two main branches of "modern physics" thus became quantum mechanics and relativity theories. Matter was investigated at atomic and subatomic levels, while the theory of relativity grew out of Einstein's studies of and theories about the effects of gravity and light on time and space.

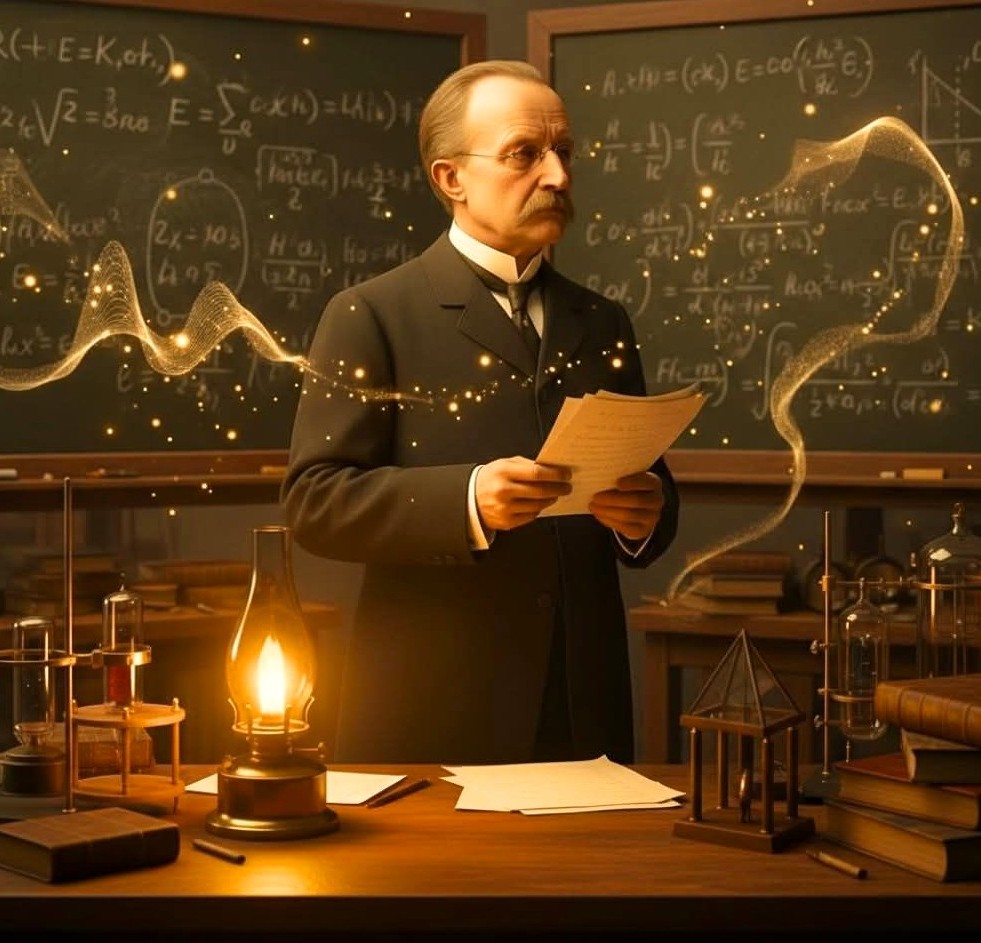

During the 1890s, it had been discovered that atoms consisted of even smaller particles than those previously assumed. Max Planck found that the theories put forward by classical physics did not work very well. For years, scientists had assumed that energy flowed evenly in the form of a wave. Planck's work now found that energy also took the form of particles, moving in individual packets that he called quanta – the plural form of the Latin quantum, meaning "how much", or "how big".

Quantum mechanics led researchers into a subatomic world where the atom's protons and neutrons are made up of even smaller particles, some of which can simultaneously exist in more than one physical place at the same time and move from one place to another, without traveling through the space that separates them. If you try to observe them an effect called wavefunction collapse might occur. Such strange, for a layman like me, completely incomprehensible phenomena have led some physicists to speculate about the existence of parallel universes and/or alternative realities.

In 1905, Albert Einstein published an article supporting the theory that light travels as small packets of energy. Einstein's theory of the effects of speed and gravity on space and time revolutionized science. His relativity theory claims that the speed of light through an empty space is constant – 299,792, 458 meters per second. No spacecraft can travel faster than that, nor can anything slow down the speed of light. To people who travel with the light, the laws of physics would seem normal. Einstein theorized that time and space were not constants, but changed depending on the movement of the observer.

In accordance with this Brave New World, literary time travel became more numerous and bolder. Just as the new physics had changed the scientific view of existence, Wells had set a new standard for the increasingly popular science fiction literature. Since then, hundreds, if not thousands, of short stories and novels about time travel have been published annually around the world. Not to mention all the movies and TV series. Some of the better of the latter can be mentioned to give an idea of the span of time travel.

The great classic is Frank Capra's Life is Wonderful from 1946 in which small-town philanthropist George Bailey is ruined by a rival and thus contemplates suicide. Standing on a bridge in a snowstorm wishing he had never been born, an angel grants his wish and George is transferred to a miserable slum named by his rival. George's brother, whose life he saved as a child, is dead, and so are the hundreds of people his brother would have saved during World War II. George's wife is an embittered maiden and their children are accordingly not born at all.

The message of the film is that every person's life has a meaning and leaves an imprint on other people's existence. George returns to a present time that has not at all changed for the worst and is met by wife, his children, his brother, the war hero, and a grateful community. Everything works out for the best and Capra's film has become one of the most beloved movies of the Christmas season and every Christmas it is broadcasted on a great variety of American TV channels.

In Planet of the Apes from 1968, the first adult film I saw on my own and which impressed me greatly. It dealt with an astronaut who travelled back to Earth in a distant future and found it to be populated not only by primitive humans but also by intelligent, talking apes.

Time dilation is a result of the theory of relativity and meant, if I have understood correctly, that the past time is different within a moving object in relation to a stationary one, something that caused Taylor and his two colleagues in Planet of the Apes to end up on a future Earth, instead of the Earth they had left. I don’t remember what happened to his astronaut companions, if I am not wrong, they just disappeared.

In the various Terminator films of the 1980s and 1990s, a Cyborg, i.e. a creature consisting of both organic, metallic and biomechatronic body parts, in this case a deceased police officer, is brought back in time from the near future to prevent global catastrophes.

In Back to the Future from 1985, teenager Marty McFly travels back to 1955 in a DeLorean sports car converted into a time machine by his good friend "Doc" Emmett Brown.

McFly narrowly manages to avoid his own mother falling in love with him and instead marrying his father, thereby saving his own future existence. In a second instalment from 1989, Marty McFly and Doc Brown are forced to travel to the future to prevent Marty's children from ruining the family's reputation and repairing the "timeline" after the villainous Biff Tannen has created a terrible future. Biff Tannen had managed to steal Marty's and Doc Brown's time car and had in it travelled back in time and provided his former self with a list of sports results that allowed him to make a fortune and turn his future self into a ruthless capitalist.

In the French Les Visiteur from 1993, one of the most popular French films ever, a knight and his squire, after a number of intricacies in connection with various witches' potions, are transported from the twelth century and end up in today's France.

The same year came Groundhog Day, in which an initially life-weary and misanthropic weatherman for unknown reasons is forced to relive the second of February again and again within the small town of Punxsutawney. Over time he manages to think about his past life and change his behaviour towards his fellow human beings and thus acquire new and better priorities.

Terry Gilliam' s 1995 Army of the Twelve Monkeys sends James Cole from 2035 back to the time before 1996 to prevent the release of a deadly virus believed to have been created by a mysterious organization called the Army of Twelve Monkeys (which is in fact innocent).

The plot is complicated with its repeated time travel, even back to the First World War and it all becomes somewhat confusing. Cole is forced to confront what has come to be known as the Cassandra complex – you know what will happen, but you cannot change neither the past, nor the future. What happens must happen, as in ABBAS's song Cassandra

Sorry Cassandra, I misunderstood.

Now the last day is dawning.

Some of us wanted, but none of us would

listen to words of warning.

But on the darkest of nights

nobody knew how to fight

and we were caught in our sleep.

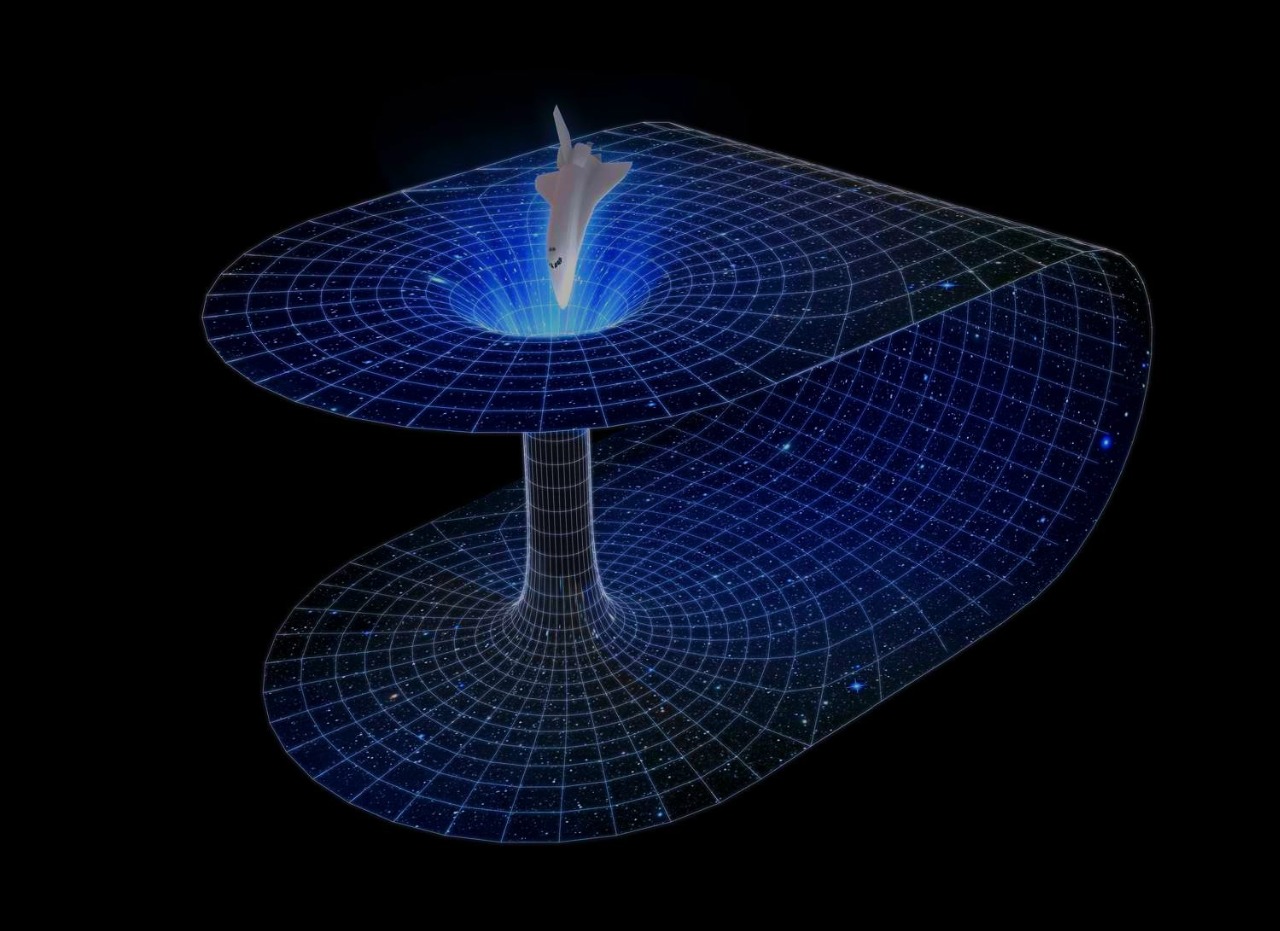

Even more confusing is Donnie Darko from 2001, which deals with adolescent anxiety, psychotherapy, déjà vu, precognition and possibly a black hole, or a wormhole. The latter is yet another incomprehensibility of the new physics. Wormholes, also known as Einstein-Rosen bridges, are a solution to field equations, i.e. calculations of how spacetime is curved by matter and energy. Worm Holes can be described as assumed "connections" between two flat parts of spacetime. These parts may be so far apart that a wormhole might appear and form a shortcut between two different points in in spacetime.

I don't understand any of this, but perhaps it can be put in connection with Kurt Gödel (1906-1978), one of history's foremost logicians and mathematicians. During the forties, when he was affiliated with Princeton University, Gödel developed a close friendship with Einstein and his interests came to be increasingly closer to philosophy (he was deeply religious) and physics.

In 1949, Gödel demonstrated the existence of closed time-like curves related to general relativity. His calculations indicated a closed "rotating universe" and, according to Gödel, it could theoretically enable time travel, to both the past and the future. Gödel's calculations, called the Gödel metric, made Einstein doubt his own theory.

In Donnie Darko , the main character exists in a seemingly normal American small-town environment, though he suffers from somnambulism and during nocturnal walks he is accosted by a lugubrious figure, in a kind of rabbit costume, who tells Donnie that his existence will end within a certain number of days. This happens, but apparently only to Donnie Darko who is snatched from his existence, probably the victim of having ended up in some kind of time distortion. The end of the film is open to different interpretations, perhaps even Donnie's mother and little sister were in the missing plane which loose engine had fallen down, crashed on the family house and apparently killed Donnie. But has this really occurred in the world he was previously a part of?

In Tony Scott's Déjà Vu from 2006, the FBI has managed to find a way to use a wormhole to go back in time and prevent a terrorist act that has already taken place – the blowing up of a boat in New Orleans that killed 543 passengers.

In Christopher Nolan's Interstellar from 2014, astronauts use cosmic wormholes and similar phenomena such as Black holes to find new settlements for humanity.

In 2000, Christopher Nolan had created a different kind of time travel in his film Memento. Leonard Shelby suffers after a traumatic experience of anterograde amnesia that causes short-term memory loss and an inability to form new memories. He therefore develops an advanced system of photographs, handwritten notes and tattoos in an attempt to find the man who murdered his wife and caused his amnesia.

A similar thicket of time travel and parallel time schedules is made up in a number of TV series. For example, the 950 episodes of Star Trek, where the spacecraft Enterprise navigates through galaxies and time zones. The series, which began in 1966, became so popular in the United States that its personalities are now by many Americans almost perceived as living persons.

I've never seen any episodes of Star Trek, but I remember when I once bought an armchair in New York and the shop assistant appreciatively commented: "A very good choice. Dr. Spock bought a similar one last week." "Dr. Spock, the paediatrician?" "No, no, I don't know who that is. I meant Dr. Spock, science officer on the Enterprise."

However, I watched with great interest all the episodes of Lost, which followed the survivors of a plane that crashed between Sydney and Los Angeles on a mysterious island somewhere in the South Pacific. Are the former air passengers alive or dead? Is the island a place in another time dimension? Is it perhaps a version of the Catholics' Purgatory?

In any case, there was a kind of primary plot with a variety of underlying flashbacks, or forward-looking ones, that deepened the characters involved.

The German series Dark, which takes place in the small town of Winden, the site of a large nuclear power plant, is, if possible, even more confusing than Lost, and like it, leaves a lot of loose ends and unresolved questions in its wake.

Dark, which is the reason why I started writing this blog post, can almost be considered a museum of theories created around the passage of time and its role in our lives – the curved space, black holes, the Cassandra Complex, parallel worlds, wormholes, encounters with one's own passed and future self, aging, the avoidance of catastrophes that have already taken place, how the past, or the future, intervene in the present, predestination, the rise and fall of the world, our personal responsibility, the power of love, etc., etc., all trapped in a strange time loop.

The couple Baran bo Odar and Jantje Friese, who created Dark, after that initiated the TV series 1899, which I found even more intriguing than they actually a little too enigmatic Dark. It is a shame that Netflix cancelled the 1899 project after the Brazilian cartoonist Mary Cagnin accused the German couple of plagiarism. I wonder. Plagiarism? In this age of quantum mechanics and shifting worlds? Incidentally, Cagnin's aesthetically and narratively quite unoriginal style does not seem to have much in common with the German couple's more sophisticated, multifaceted and now prematurely unfinished storytelling.

The influence of mysterious pyramids, which form the basis of Cagnin's plagiarism accusation, seems downright ridiculous given that pyramid power has been a common trope in the science-fiction genre ever since the New Age guru Patrick Flanagan introduced his mumbo jumbo around power-producing pyramids in the early 1970s. They have since appeared in all sorts of stories, such as in the 1994 film Stargate, or in the much more comical Illuminatus trilogy (1984) by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson, as well as in Terry Pratchett's Pyramids (1989), in which pyramids actually affect different dimensions of time.

Along with wormholes, the Multi-Worlds Interpretation (MWI) occupies a prominent place in Dark. It is an interpretation of quantum mechanics that claims that the universal wave function is real and permanent, consequently there is no wave function collapse. This means that the outcomes of quantum measurements are realized within the different "worlds" that make up part of a "multi-universe".

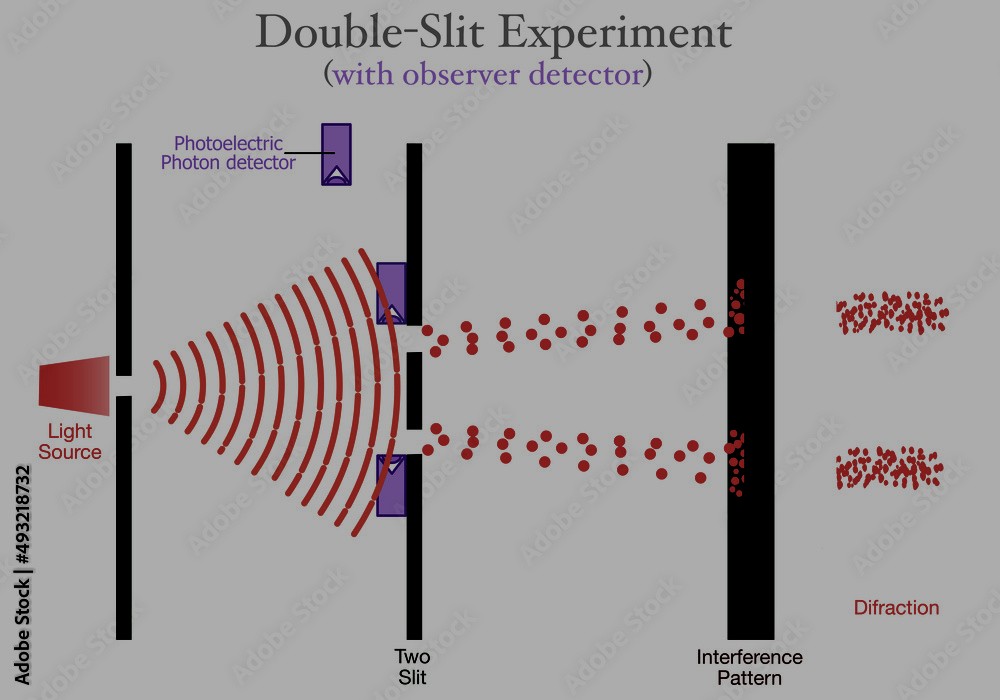

As with so many other interpretations present in quantum mechanics, the multi-world interpretation is justified by the so-called Double-Slit Experiment. When particles, such as electrons, are sent through two slits towards a screen, they create an interference pattern on the screen, even when they are sent off one at a time, suggesting that each particle in some way influences/transforms itself. This phenomenon indicates that objects at the quantum level, such as photons or electrons, behave like waves until they are measured, at which point they behave like particles.

The experiment has been taken as evidence that the physical reality is associated with a wave function inherent in its most elementary particles and that this wave function does not collapse, as previously assumed, but is transformed. Consequently, there are several parallel universes, which can only interact with each other through interference.

Such parallel worlds exist in Dark, but they have appeared on several previous occasions, such as in Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle from 1962. The novel takes place in 1962, fifteen years after Nazi Germany and Japan won World War II and the victorious powers have divided the United States between them, with a "neutral" zone between the two spheres of influence. However, there exists a forbidden "novel", The Grasshopper Lies Heav, which tells us that this is an illusion. It is never really clear what is reality, or whether it is perhaps just a writer's imaginary creation, a novel within a novel.

The excellent TV series that was later made on The Man in the High Castle, makes it all quite clear. It is in a parallel reality that the Japanese and the Germans have triumphed. There is another world where the Allies have triumphed and where life is completely different. Grasshopper Lies Heav, is in the series not a novel but hidden documentaries that truthfully depict how the Allies won the war – but ... Not here and now, not in this reality, but in a parallel world.

The different worlds make me remember a series of books that my oldest daughter was very fond of. Especially one that was about how a spirit fulfilled different desires. Each chapter ended with different choices and the story continued depending on the choice you made.

That book was read to pieces and I guess my daughter still remembers it. It was part of a book series called Choose Your Own Adventure, and the books were written in the second person. Between 1979 and 1998, they had sold more than 250 million copies and been translated into 40 languages. Time travel was a frequent theme in several of them.

I don't know if the Swedish author Peter Glas are familiar with those books. In any case, in 2015 he wrote the fascinating Amber Kiss, which dealt with Gabriel's life choices. He falls in love and is invited home for dinner by the coveted woman, but ... Should he accept, or instead go to a business meeting that could make him wealthy? The reader decides. If Gabriel accepts the dinner the reader gets to know how it unfolded. However, if it is the business meeting that Gabriel prefers to prioritise the reader will have to scroll to another page. And so, it continues throughout the book, where the reader is left with one choice after another, and soon we discover that the choices are generally about love, money or career, and consequences are accordingly.

.jpg)

As early as 1963, the Argentine writer Julio Cortázar had written the novel Hopscotch which was divided into 155 chapters and which, according to the author, could be read in different order, all according to a list of numbers given by Cortázar. If the novel was read in agreement with the multitude of options indicated by the different sequences of numbers, several different stories would emerge.

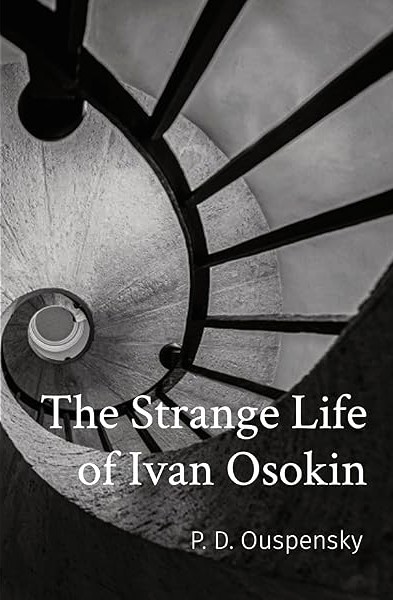

The most masterful story in the genre of "alternate realities" was written by Cortázar's compatriot Jorge Luis Borges. His story Garden of Forking Paths from 1941 is in many aspects the perfect short story: short, dense, original, strange, contemplative and thought-provoking.