Blog

"Min IQ är en av de högsta - och ni vet det! Känn dig inte så dum eller osäker för det. Det är inte ditt fel ", en tweet av Donald Trump den 8:e maj 2013.

En scen som dykt upp i en eller annan skräckfilm är när en person sliter bort sitt ansikte. Exempelvis i Ingmar Bergmans Vargtimmen där konstnären Johan beskriver hur han plågas av föreställningen om hur en gammal dam med hatt tar av sig hatten och hela ansiktet följer med, som om det varit en mask.

Inom japansk folklor finns ett monster som i ett skräckfyllt ögonblick tar av sig ansiktet, som vore det en mask, och avslöjar att det inte dolt några ansiktsdrag. I Japan kallas ett sådant monster Noppera- Bo och en del av den skräck handlingen orsakar är att monstret först bar drag av någon du känner, eller till och med hade ditt utseende.

Jag antar Donald Trump's ”personlighet” måste ha tett sig attraktiv för sina väljare. Men jag frågar mig vad som gömmer sig bakom denna förbryllande fasad av grovt språk, förolämpningar, häpnadsväckande överdrifter, lögner och storhetsvansinne. Jag fruktar att Trumps beteende döljer någon form av noppera-bo, en formlös personlighet eller en förvandlingskonstnär, liknande de som Cristopher Lasch beskriver i sin bok Den narcissistiska kulturen. En värld där alltfler alienerade personer har en benägenhet att betrakta världen, även om de uppfattar den som tom och meningslös, som en spegling av dem själva. Något som gör att de inte vill konfrontera sig med sitt ”inre”, sina egna tankar och sin oro. Istället söker de andras uppmärksamhet och sympati genom att framställa sig som en slags ideal. Om andra människor bir förförda att tro på narcissistens skådespeleri blir dennes självkänsla förstärkt.

Redan under artonhundratalet hade USA förvandlas till ett underhållningsmecka, mot vilket invånarna i en alltmer globaliserad värld vände sin uppmärksamhet för att därigenom kunna hänge sig åt glömska och förtrollning.

När vi för några år bodde i New York förvånades jag över att även om mycket inte fungerade kunde vi alltid vara förvissade om att Broadway ständigt bjöd på förstklassig underhållning. Jag är inte säker på om samma kvalitetsbedömning kunde tillämpas på pressen, men jag imponerades av The New York Review of Books, The New Yorker och i viss mån även av The New York Times. Men jag var likväl tvungen att hålla med Cristopher Lasch's åsikt om att massmedia, med sin kändiskult och sina försök att omge förmögna och priviligierade människor med glamour och spänning, har gjort amerikaner till ett folk av ytliga konsumenter av underhållning i olika former. Medierna konkretiserar och intensifierar drömmar om ära och berömmelse medan de uppmuntrar människor att identifiera sig med stjärnorna och förakta flocken av medelmåttor. Därmed finner genomsnittsamerikanerna det allt svårare att acceptera sin vardagsbanalitet. I det de upplever som sin obetydligs tomhet försöker de efter bästa förmåga värma sig i mediernas falska reflektion av stjärnornas glöd.

En glöd som intensifieras genom hastigheten på medieteknikens utveckling som gjort det möjligt för en tidigare oöverträffad masskommunikation att påverka sin ständigt växande globala publik, som stimuleras till en ökande längtan efter berömmelse, lyx och pengar, massor med pengar. Låt oss lyssna till profeten själv, den uppenbart egenkäre Donald Trump:

En del av min tjuskraft kommer från det faktum att jag är mycket förmögen. [...] När jag tror mig ha rätt, stör mig ingenting [...] Jag kommer att vara den störste arbetsskapande president som Gud har skapat. [...] Jag spelar på människors fantasier. Folk kanske inte tänker så stort på egen hand, men de kan bli mycket entusiasmerade om någon gör det åt dem. Det är därför som en och annan överdrift aldrig skadar.

Trumps karaktär är som manna från himlen för den amerikanska drömfabriken och givetvis kan det inte undgå någon att även Trumps förmögenhet finner sitt ursprung i andra människors förhoppningar om pengar, berömmelse och ära. En salighet som enligt mediaillusionen kan uppnås utan ansträngande arbete - genom kasinon, dokusåpor och skönhetstävlingar. Trump nådde sina största framgångar genom dokuextravaganzan The Apprentice, skapad av den brittiskfödde TVproducenten Mark Burnett, skyldig till flera andra prisade, men i slutändan tämligen bristfälliga produkter, bland dem en sirapslen bibelserie producerad för History Channel.En stor hit med en Jesus som enligt The New York Times såg ut som en "surfargrabb".

The Apprentice inleddes med en klassisk Rhythm and Blues sång, The O´Jays For the Love of Money:

Några måste ha dem

Några behöver dem

Lyssna på mig, för att uträtta, uträtta dåliga gärningar med dem.

Du vill göra gott, göra gott, uträtta goda gärningar med dem.

Talar om kontanter, pengar

Talar om kontanter - dollarsedlar.

Handplockade unga, attraktiva tävlanden delades in i två lag, så kallade ”företag”. Under varje episod utsågs en medlem av varje lag för att agera "projektledare" och leda sina lagkamrater vid lösningen av olika uppgifter; som produktutveckling, välgörenhets- eller reklamkampanjer, marknadsundersökningar, m.m. Vinnaren av varje avsnitt utsågs av Donald Trump och hans rådgivare, medan den svagaste medlemmen i varje grupp eliminerades från tävlingen med Trumps hårda ord: "Du är avskedad".

Säsongsvinnaren utsågs till ”vice VD”, fick titeln ”ställföreträdare för företagsledaren” och ett USD 250 000 årskontrakt som talesman för Trump Organization. Serien presenterade kontinuerligt produkter marknadsförda av Trump eller hans familjemedlemmar. Serien blev mycket populär. Donald Trump strålade i dess glans och kom uppenbarligen att betrakta sig själv som en överlägsen bedömare av andras utseende, förmåga och karaktär:

Om jag var ansvarig för The View [en populär pratshow], skulle jag sparka Rosie O'Donnell [komiker och tv-personlighet]. Jag menar, jag skulle titta henne rätt in i hennes fula, feta ansikte och säga "Rosie, du är avskedad.

Jag antar att den typ av exponering The Apprentice skänkte Donald Trump inte kunde ha varit speciellt nyttig för en person som lider av narcissistisk personlighetsstörning (NPD), ett patologiskt tillstånd som kännetecknas av överdrivna känslor av självtillräcklighet, överdrivet behov av beundran, samt brist på empati. Offer för NPD lider av en sjuklig fixering vid framgång, makt, rikedom och utseende. De tenderar också att dra nytta av människor i sin omgivning, alltid på jakt efter "vad kan de kan ha för nytta för mig". Narcissistiskt beteende tenderar att utvecklas i tidig vuxen ålder, och tar formen av mobbning av enskilda, udda individer, hänsynslöst och ”upproriskt” beteende samt en extrem känslighet för varje form av kritik.

Mark Burnett, fick sin idé till en verklighetsbaserad TV-show under ledning av Donald Trump efter att ha läst hans bok The Art of the Deal från 1987 (den har inte översatts till svenska, men titeln kan möjligen tolkas som Affärsuppgörelsens konst). Varje episod av den första säsongen av The Apprentice, som hade premiär 2004, inleddes med scener som skildrade New Yorks hektiska miljö, ackompanjerade av Trumps dramatiska speakerröst. Till slut ser vi Trump sittande i baksätet av en limousin medan han skamlöst skryter om sina fantastiska kunskaper och stora framgångar samtidigt som vi ser klipp med hans hotell, flygplan och kasinon. Donald Trump ställer den retoriska frågan ” Vem vill bli miljardär?” och förklarar sedan: "Jag har bemästrat konsten att göra profitabla affärsuppgörelser. Jag har gjort namnet Trump till ett högkvalitativt varumärke." Uttalandet följdes av en bild av The Art of the Deal´s omslag alltmedan Trump förklarade att han nu som en mästare, a master är på jakt efter en lärling, an apprentice. Den egentlige och nu mycket ångerfulle författaren till boken, Tony Schwartz, har långt senare konstaterat:

The Apprentice är mytbildning på steroider. Det finns en rak linje från den boken fram till showen och sedan till 2016 års presidentkampanj.

Tony Schwartz är en journalist som under mer än tio år hade arbetat för olika prestigefyllda New York tidningar då han i början 1986 blev kontaktad av sin agent som frågade honom om han var villig att skriva en bok om Donald Trump. Till en början var Schwartz motvillig, men som han senare förklarade: "Jag var alltför orolig för pengar. Jag trodde pengar skulle göra mig trygg och säker - eller så var det var min rationalisering för vad jag gjorde." Schwartz känner sig nu ansvarig för Trumps senaste triumf och redan i juni i år berättade han om sin stora fruktan för att Trump verkligen skulle kunna vinna presidentskapet och för att lätta sitt dåliga samvete kontaktade han The New Yorker: "Jag är tvingad att släpa på detta till slutet av mitt liv. Det finns ingen möjlighet att rätta till vad jag gjort."

Schwartz är rädd för att Trumps presidentskap kommer att innebära en katastrof för hela nationen och en stor fara för resten av världen. Schwarz lärde sig frukta den person han under en tid samarbetade så nära med, vars medvetande han ville tränga sig in i så att han skulle kunna skriva en trovärdig biografi. Schwartz påstår att han inte fruktar Trumps idéer - han har antagligen ingen ideologi över huvud taget. Schwarz tvivlar på om Trump någonsin har bildat sig en klar föreställning om någonting. Enligt Schwartz, är ytligheten hos Trumps kunskaper och åsikter "ofattbar". De flesta av Trumps uttalanden grundar sig på en skrämmande okunnighet, godbitar han plockat från TV och personer i sin omgivning. "Det är därför han föredrar TV som sin främsta nyhetskälla, informationen kommer i lättsmälta småbitar.” Vad Schwartz misstänker vara den drivande kraften bakom Trumps handlande är hans omättliga hunger efter pengar, beröm, bekräftelse och kändisskap.

Trump står för många av de saker jag avskyr: hans vilja att köra över människor, överdådiga, smaklösa, gigantiska tvångstankar, en absolut brist på intresse för något utöver makt och pengar, [i boken] har jag skapat en karaktär betydligt mer vinnande än den faktiske Trump.

Trump är oerhört stolt över The Art of the Deal. Under ett massmöte under sin valkampanj frågade han den entusiastiska publiken hur många av dem som hade läst hans första bok, The Art of the Deal. Hundratals händer höjdes och Trump förklarade:

Det är min andra favoritbok genom tiderna. Vet ni vilken min första är? Bibeln! Inget slår Bibeln!

Uttalandet möttes av dånande applåder. När Trump kämpade hårt med de republikanska ledarna för att kunna bevisa att han var en värdig presidentkandidat förklarade han:

Jag gick till Wharton School of Finance och var en strålande student. ... Jag går ut ur skolan, jag skapar en enorm förmögenhet. Jag skriver en bok som heter The Art of the Deal, den bäst säljande affärsboken genom tiderna, åtminstone tror jag det, fast jag är ganska säker på att det är på det viset. Den är verkligen en nummer ett monsterbästsäljare. Jag gör The Apprentice, en enorm framgång, ett av de mest framgångsrika TVprogrammen.

Efter det att en före detta journalistbekant till honom publicerat en bok om sitt samröre med Trump skrev denne ett öppet brev till The New York Times, som publicerat en välvillig recension av boken. Trump hävdade att författaren till Trump and Me, Marc Singer, i motsats till Donald Trump själv "inte var född med någon större skrivförmåga" och till Singer skrev han: "Mark - du är en total loser - och din bok (och dina andra skrifter) suger! Bästa hälsningar Donald. P.S. Och jag hör att den säljer dåligt."

Trots allt skryt om sitt författarskap bedyrar Tony Schwarz att Trump inte skrev en enda rad av The Art of the Deal, i slutet av den besvärliga och plågsamma skrivprocessen begränsade sig Trump till att stryka ett par kritiska omnämnanden av affärskollegor. När The New Yorker bad Trump kommentera Schwarz påstående svarade han:

Han [Schwartz] skrev inte boken. Jag skrev boken. Jag skrev boken. Det var min bok. Och det var en nr 1 bästsäljare, och en av de bäst säljande affärsböckerna genom tiderna. Vissa säger att det var den bäst säljande affärsboken någonsin.

Och då The New Yorker vände sig till Howard Kaminsky, tidigare chef för Random House, som publicerade The Art of the Deal, och frågade om Trumps uttalande var sant, skrattade han och sa: "Trump skrev inte ens ett vykort för oss". Tony Schwartz antar att Trump's udda och upprörande personlighet vid det här laget har övertygat honom om att han faktiskt skrev boken själv.

Trump passade inte modellen för någon människa jag mött tidigare. Han var besatt av publicitet, och han brydde sig inte om vad du skrev. Trump har enbart två känslolägen. Antingen du är en tarvlig förlorare, en lögnare, vad som helst, eller så är du bäst, störst. Jag blev den störste. Han ville betraktas som en tuff kille och han älskade omslagsbilden.

Schwartz försäkrar att om han hade skrivit The Art of Deal idag skulle det ha blivit en fullkomligt annorlunda bok. Han skulle kalla den The Sociopath, ”Socoipaten”, en sjukdomsbeteckning som är vanligare i USA än i Sverige och där förklaras som ”en abnorm personlighet som lider av sin abnormitet och/eller åstadkommer skada i samhället”. Schwartz skulle definitivt inte ha skrivit sin nya bok tillsammans med Trump, inte enbart för att han anser honom vara galen, men även på grund av att det var en svår prövning att skriva The Art of the Deal, främst på grund av Trumps brist på tålamod, hans koncentrationsförmåga är ytterst begränsad, något som flera personer i Trumps omgivning har konstaterat.

Marc Singer är en annan författare som tillbringat en längre tid med Trump. Singer gjorde det på uppdrag av The New Yorker som beställt en ”personstudie” av Trump. Den självupptagne magnaten accepterade med entusiasm förslaget om att Singer skulle följa honom under hans arbete och fritid, men journalisten blev snart bestört över hur ytlig och vulgär hans värd tycktes vara. Det var svårt att förstå hur så många kommit att betrakta denne uppenbart falske och okunnige man som en slags övermänniska. Singer försökte desperat att bli vän med Trump, för att därigenom kunna pejla hans inre djup och övertygelser. Singer fann dock att Trump främst var inriktad på pengar och vackra damer. Han var en bra golfspelare, men gillade inte fysisk träning, sov enbart fyra timmar om dygnet och sedan hans bror dött som obotlig alkoholist rörde Trump inte någon form av alkohol, fast han hade ett välförsett lager för sina gäster.

Trump ljög, lätt och skamlöst, samtidigt som han tycktes lida av en märklig form av självförnekelse. Han hade skapat en image som tycktes vara en karikatyr av en serietidningsmiljonär. Hans tillvaro framstod enligt Singer som en ”opera-buffa parodi på rikedom". Singer anser att introspektion vore fatalt för Trump, det skulle döda varumärket. I en Playboyintervju från 1990, betonade Trump vikten av intensiv, högt uppdriven aktivitet. Han kallade det "kontrollerad neuros":

Jag tror verkligen att en framgångsrik man aldrig är riktigt nöjd, eftersom det är missnöje som driver honom. Jag har aldrig träffat en framgångsrik person som inte samtidigt var neurotisk. Det är inte ett fruktansvärt tillstånd ... kontrollerade neuroser. Kontrollerade neuroser förutsätter att du har en enorm energi, ett överflöd av missnöje som oftast inte syns. Det gäller också att inte sova bort sitt liv. Jag sover inte mer än fyra timmar per natt.

Liksom Schwartz förvånades Singer av Trumps begränsade koncentrationsförmåga. Han talade ständigt i sina mobiltelefoner, skickade SMS, alltmedan han släppte lös laviner av epitet och intetsägande fraser, rikligt kryddade med ord som "fantastiskt", "häpnadsväckande" och "otroligt" och en uppsjö av synonymer för "största" och ”väldigast”. Universum kretsade kring Trump alltmedan han var fastlåst i sin roll. Om han inte förmådde pressa något ur den ignorerade han sin omgivning. Inte enbart Schwartz och Singer, utan flera andra som varit nära Trump uttrycker allt som oftast en viss utmattning. Jag kan lätt föreställa mig hur det kan vara att bevittna Donald Trump på nära håll. Det är vore kanske något i stil med att ständigt få uppleva en till leda upprepad, överlastad revyföreställning, eller kanske en groteskt överdriven Cecil B. DeMille extravaganza utan någon som helst möjlighet att gripa in i handlingen.

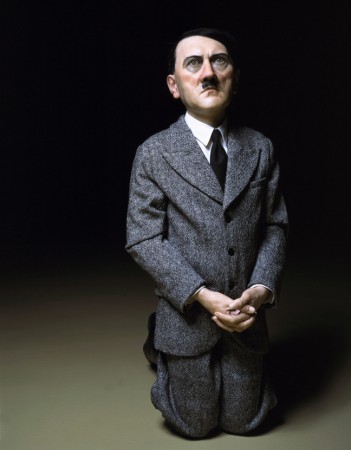

Schwartzs beskrivning av den ständigt verksamme, övervitaminiserade Trump får mig att tänka på Chaplins skildring av Adenoid Hynkel, alias Hitler, i hans geniala Diktatorn, som i stor brådska och snabb följd dikterar brev, poserar för konstnärer, slänger ur sig ogenomtänkta order, kastar sig över sin älskarinna, etc, etc ., hela tiden fastlåst i ett patetiskt försök att upprätthålla sin status som en stor macholedare. Schwartz pekade på Trumps "unika talang för att vara Trump”:

Jag måste göra en massa saker själv. Det tar så mycket tid. Julio Iglesias kommer till Mar-a-Lago, men jag måste själv ringa till Julio och jag måste ha lunch med Julio. Jag har Pavarotti som kommer. Pavarotti framträder inte för vem som helst. Han är den högst betalde artisten i världen. En miljon dollar för varje föreställning. Den svåraste killen att få att uppträda. Om jag kallar honom, kommer han och gör det för en betydligt mindre summa än han brukar begära. Varför? För att de gillar mig, för att de respekterar mig, jag vet inte.

I öppningsscenerna till The Apprentice förklarar Trump hur tillfredsställd han känner sig genom sin enorma framgång och hur roligt han har det. Men vad är nöje för Trump? De "hem" han skapat kring sig och sin familj är som kulisser för överdådiga operor, inspirerade av Vinterpalatset i St Petersburg, och hans kasinon. Enligt Trump är de platser "som tagna ur en dröm", där han själv är förgrundsfiguren, en vulgär avbild av Ludvig XIV, omgiven av sina tjänare, sitt svassande hov av beundrande lismare.

I en 1990 Playboyintervju förklarade Trump att hans yacht, hans överdådiga kasinon, byggnader och lägenheter som skimrar av marmor, brons och guld alla enbart var "rekvisita för showen", och tillade sedan att showen är "Trump" och att föreställningarna är utsålda överallt.

Och låt mig säga er, att exponera rikedom är bra. Det visar folk att man kan bli framgångsrik. Det visar ett sätt att leva. Dynasty [en såpopera om oljemiljonärer som gick i mer 220 avsnitt mellan 1981 och 1986] gjorde det på TV. Det är mycket viktigt att människor strävar efter att vara framgångsrika. Det enda sättet du kan göra det är om du får se hur de rika har det.

De olika teaterkulisserna för the Trump Show är fyllda till brädden med dyrbar, vulgär ornamentik:

Gobelänger, väggmålningar, fresker, bevingade statyer, porträtt i naturlig storlek av Trump (ett med titeln ”Visionären"), väldiga marmorbadkar, blomsterprydda silversamovarer, korintiska kolonner i vattrad marmor, bländande ljuskronor, intarsia överallt, ett överflöd av guldförgyllning.

Däremot kan man ingenstans i denna sagolika skyltfönstervärld finna en endaste bok. Nej, jag har fel, det finns faktiskt ett undantag. Under Trumps hårda skilsmässokamp med Ivana Trump under 1990 skrev den legendariska undersökande journalisten Marie Brenner en insiktsfull, omfattande och svidande artikel om Donald Trump: Efter Guldruschen. Marie Brenner kände både Ivana och Donald och hade exklusiv tillgång till dem båda. Hon rörde sig dessutom i miljonärparets umgängeskrets. De borde dock ha aktat sig för henne. Det var Brenners artiklar som senare avslöjade den så kallade Enronskandalen, då det visade sig att en oljejätte vilade på lerfötter av bokföringsbedrägerier och korruption. Hennes avslöjanden om ljusskygga intriger inom tobaksindustrin blev till en film med Russell Crowe och Al Pacino, The Insider. I sin artikel berättar Brenner hur en bitter Ivana Trump attackerar Donald:

Hur kan du säga att du älskar oss? Du älskar inte oss! Du älskar inte ens dig själv. Du älskar enbart dina pengar.

Genom sin självförnekelse har Trump, enligt Schwartz, blåst upp sitt ego till sådana proportioner att det har slipat ner de skarpa och ojämna kanterna av hans karaktär och förvandlat honom till en produkt som ständigt placeras i strålkarskenet. När han träffade Ivana deklarerade Trump att han ville ha minst fem barn "som i min egen familj, för om de är fem, vet jag att en garanterat kommer att bli som jag."

När Marie Brenner försökte skrapa på ytan av Donald Trumps persona genom att antyda att hans hopp om ett barn som skulle likna honom kunde ha samband med hans olycklige och alkoholiserade bror Freds död vid fyrtio års ålder. Donald svarade:

Jag hade framgång och det satte press på Fred. Vad är detta, en psykoanalys av Donald?

Trumps uppenbara olust att minnas detaljer från sitt förflutna var något som komplicerade Schwartzs uppgift att skriva The Art of the Deal. Så snart Schwartz sökte efter Trump's inre känslor, till exempel genom att prata om hans barndom och ungdom, hans kontakter med familj, vänner och skolkamrater, blev Donald orolig "likt en daghemsunge som inte kan sitta still."

När Schwartz pressade Trump ytterligare verkade det som om han inte kom ihåg så mycket av sina år innan framgångarna och han gjorde det klart att han var uttråkad. Eftersom Trumps bidrag till sin biografi blev intetsägande, censurerade och ytliga beslöt sig Schwartz för att upphöra med sina intervjusessioner och sin jakt efter Trumps personliga uppfattningar och inre känsloliv.

Det är omöjligt att för mer än några minuter hålla honom fokuserad på något ämne, annat än sitt ständiga självförhärligande.

Liksom många andra som har försökt att pussla ihop Trumps känsloliv tvingades Schwartz begränsa sig till intervjuer med människor som stod nära Trump och den information han kunde plocka ihop från media. Det var också mycket svårt att diskutera idéer med Trump, i synnerhet som Schwartz misstänkte att "Trump under sitt vuxna liv aldrig har läst en bok rakt igenom ". Han såg aldrig någon bok liggande på Trumps skrivbord, eller någon annanstans i hans kontor, eller i hans olika lägenheter.

Emellertid motsägs Schwartz av Ivana Trump. Under ett av sina desperata utbrott om ex-makens egenheter berättade Ivana för Marie Brenner att Trump antagligen läst en bok med Hitlers samlade tal, My New Order, som han hade i ett skåp vid sin säng. Men även det visade sig vara osäkert, när Brenner frågade Donald Trump om hitlerboken svarade han:

Egentligen var det min vän Marty Davis från Paramount som gav mig en kopia av Mein Kampf och han är en jude.

Fast Davis, en hetlevrad företagsledare som omformat Gulf and Western Industries till mediagiganten Paramount Communications, berättade för Brenner att det inte var Mein Kampf han gett till Trump och att han tvivlade på om hans vän ens läst den boken:

Det var My New Order, en samling med Hitlers tal, och inte Mein Kampf. Jag trodde att han skulle finna den intressant. Det stämmer att jag är hans vän, men jag är inte jude.

Varför skulle Davis få för sig att skänka en samling med Hitlers tal till Donald Trump? Antagligen för att han antog att Trump, som en advokat berättat för Brenner, var "en övertygad anhängare till läran om Den Stora Lögnen. Om du upprepar något om och om igen, kommer folk slutligen att tro dig."

Den Stora Lögnen, på tyska Die Grosse Lüge, är en propagandateknik som allmänt tros härröra från ett avsnitt i Hitlers Mein Kampf där han beskriver vad han anser vara "marxisternas och judarnas'" smutskastning av hans politiskt allierade General Erich Ludendorff som en av de som var skyldiga till Tysklands nederlag i Första världskriget:

Man utgick därvid från den riktiga principen att ju större lögnen är, desto större är utsikterna för att den ska bli trodd, eftersom de flesta människor inom folkets stora massa i djupet av sitt hjärta visserligen inte medvetet och avsiktligt är dåliga, men så enkelt och primitivt konstruerade att de lättare faller offer för en stor lögn än en liten. De ljuger själva mången gång i smått, men skäms för att göra sig skyldiga till en stor lögn. En sådan får alltså inte plats i deras medvetande, och de tror därför inte heller andra om en så oerhörd fräckhet och en så infam förvrängning. Även då de upplyses om detta tvivlar och vacklar de länge, och försöker tro att lögnen åtminstone har någon grund, varav följden blir att en smula fastnar även av den fräckaste lögn, ett faktum som alla stora lögnkonstnärer och lögnföreningar i denna världen alltför väl känner till och utnyttjar på det gemenaste sätt.

Det är tveksamt om Trump har läst detta. Men Schwartz som efter att ha misslyckats med sin trumpintervjuer fick tillåtelse att osedd lyssna på hans telefonsamtal försäkrar att Trump använder sanning och lögn på ett högst personligt sätt. Enligt Schwartz är Trumps samröre med folk i stort sett enbart show business, en kombination av smicker, skryt och mobbning. Schwartz kunde inte upptäcka någon "privat Trump", föremålet för hans planerade biografi verkade uteslutande drivas av allmänhetens uppmärksamhet, av att ständigt befinna sig på scenenens centrum: "Allt han är, är ´stomp, stomp, stomp´ – ett sökande efter ytligt erkännande." Schwartz kom till slutsatsen att Trump inte vill konfrontera sig med något "inre jag". I en Playboyintervju från 2004 förklarade han:

Många människor går till psykiatriker eftersom de inte är tillräckligt upptagna. Jag tillbringar så mycket tid med att tänka på byggnader och affärsavtal och nattklubbar och göra vad jag gör att jag inte har tid för några mentala problem. Psykiatri är inte min grej [...] Jag har faktiskt inte något dåligt humör. Jag kallar det kontrollerat våld. Jag blir arg på människor för deras inkompetens. Jag blir arg på människor som får betalt en massa pengar och inte ser tillräckligt vakna och slipade ut då de jobbar för mig. En anledning är att jag vill göra allt bättre än alla andra. Det är en anledning till varför jag får ut mer per kvadratmeter än andra fastighetsägare. Det är en förklaring till varför jag är så framgångsrik.

Som den skådespelare han är, uppträder Trump ständigt. Hans mediaföreställningar är en chimär som har mycket lite att göra med verkligheten. Lögn har blivit en del av hans skådespelerirutin:

Att ljuga är en självklarhet för honom. Mer någon annan jag mött har Trump förmågan att övertyga sig själv om att allt han säger vid en given tidpunkt är sant, eller en slags sanning, eller åtminstone borde vara sant. Hur mycket han har betalat för något, eller vad en byggnad han ägde var värd, eller hur mycket ett av hans kasinon tjänade in när det i själva verket var på väg till konkurs.

Då besökare visas runt i hans märkliga, påkostade boningar, guidar Trump dem som om de hamnat i ett museum. Han berättar vad allt har kostat honom, hur exklusivt materialet är - marmor från Carrara, kranar, handtag, gångjärn och till och med skruvar av solitt guld. Skor från berömda basebollspelare, Mike Tysons segerbälte som han tilldelades då han vann världsmästerskapet i tungviktsboxning och en mängd liknande troféer. Matsalen med sin skulpterade elfenbensfris. "Jag erkänner att elfenben är lite av ett nej-nej". Marmorkolonner i onyx som har fraktats dit ”från ett slott i Italien", en ljuskrona som ursprungligen hängde i "ett slott i Österrike", en toalett i blå onyx ”från Afrika”.

Allting runt Trump är show, kanske detta är en anledning till varför massmedia är så attraherad av honom, allt i enlighet med Cristopher Lasch's observation att media dyrkar kändisskap, glamour och spänning. Trump är en kändis och därmed undviker han själsdjup och introspektion, komplikationerna i det inre av den mänskliga själen. Marc Singer berättar om en resa med Trumps privata jetplan från Miami till Atlanta:

Trump bestämde sig för att vi skulle titta på en film. Han hade tagit med sig Michael, en ny release, men efter tjugo minuter tröttande han. [Egentligen ingenting som Trump kan klandras för. Michael är en tämligen usel film med John Travolta i huvudrollen som ärkeängel].Trump poppade ut Michael ur videoapparaten och bytte till en gammal favorit, en Jean Claude Van Damme våldsfilm vid namn Bloodsport, som han ansåg vara "en otroligt fantastisk film" och gav sin son i uppdrag att snabbspola framåt genom alla handlingsrelaterade moment -Trumps mål var "att få en två timmars film ner till fyrtiofem minuter "- han avlägsnade alla eventuellt lugnande pauser mellan näshamrande, njurmörande och skenbensknäckande. När en biffig skurk var i färd med att trycka ihop en normalstor, sympatisk kille och fick ett förödande slag mot pungen, skrattade jag. "Erkänn, du skrattar!" skrek Trump. "Du tänkte skriva att Donald Trump var förtjust i denna löjliga Jean-Claude Van Damme film, men är du villig att skriva att du också gillade den?”

Machoimagen verkar vara ytterst väsentlig för Trump. Han är fascinerad av alla varianter as s.k. blodssport. En stor fan av boxning och fribrottning, men den enda sport han personligen utövar är golf. I sin ungdom var Trump ganska bra på baseball, men känd för sitt dåliga temperament och ovilja att förlora. Han sägs att i ilskan ha slagit sönder flera basebollträn. Vid sin lyxiga resort, Mar-a-Lago, har Trump ett välutrustat gym, men besöker det enbart för massage. Marc Singer kommenterade det stora antalet lättklädda, vackra damer på gymmet och Trump förklarade då att han tyckte om att omge sig med vackra kvinnor. Han introducerade Singer för en av de eleganta damerna och förklarade att hon var en ”magnifik, högutbildad läkare”. När Singer diskret frågade Trump från vilket universitet hon fått sin examen viskade Trump i förtroende, "strictly off the record", något han gjorde hela tiden, även om han egentligen inte alls hade något emot att hans ”förtroliga” uttalanden publicerades. Trump fejkade ständigt intimitet och exklusivitet.

"Jag är inte helt säker på det", svarade han. "Baywatch Medical School? Låter det rätt? Jag ska berätta sanningen. När jag såg Dr. Gingers fotografi, behövde jag verkligen inte titta på hennes CV eller någon annans heller för den delen. Om du frågade om vi anställde henne eftersom hon hade utbildats på Mount Sinai Hospital i femton år, skulle svaret bli nej. Och jag skall berätta varför: Efter det att hon tillbringat femton år på Mount Sinai, skulle vi inte ens vilja titta på henne.”

I själva verket har Dr. Ginger Lee Southall sin examen från State University of New York of Stony Brook och fick sin doktorsexamen från New York Chiropractic College. Hon propagerar för närvarande på TV och över nätet för sina de-tox produkter som The Rainbow Juice Clearance.

Intresset för paranta, välsvarvade kvinnor, som dessutom kan presenteras som intelligenta, är något Trump delar med en hel del, ofta tämligen till åren komna, testosteronstinna mediemoguler. Det räcker med att titta på de hårdsminkade, långbenta amerikanska skönhetsideal som i slimmade klänningar exponeras på den trumpglorifierande Fox Channel. Men, eftersom Fox också kräver att de anställda damerna skall vara smarta har kanalen fått åtskilliga problem. Megyn Kellys fall är avslöjande.

Det var efter en ökänd Fox News debatt som Trump under en CNNintervju avfyrade en osmaklig harang om Kelly:

Visst, jag har inte mycket respekt för Megyn Kelly. Hon är en lättviktare och du vet, hon kom dit och läser högt ur sitt lilla manus och försöker vara tuff och skarp. Och när du träffar henne inser du att hon inte är speciellt tuff och inte heller vidare skarp. Hon kommer ut dit och börjar ställa en massa löjliga frågor och man kunde se hur det kom blod ur hennes ögon, blod ur hennes... var som helst.

I en nyutkommen bok, Settle for More, Begär mer, visade Megyn Kelly att den här typen av macho mobbning inte alls är ovanlig inom den maskulint dominerade medievärlden. Många år innan den fatala debatten hade Kelly ett inslag i sin Fox Channel show om Donald och Ivana Trumps skilsmässa, efteråt ringde en rasande Trump till henne och hotade:

Du hade ingen orsak att visa det där inslaget i din show! Åh, jag nästan släppte lös mitt vackra Tweet på dig och jag är fortfarande kapabel att göra det.

Trump förverkligade inte sitt hot utan svalde förtreten, men blev åter uppretad då Kelly i en senare intervju avslöjade hans bristande beläsenhet genom att fråga efter hans favoritböcker och Trump efter viss tvekan svarade På västfronten intet nytt, något som gjorde att mediadrevet omedelbart uppmärksammade att just denna roman hade varit obligatorisk läsning på New York Military Academy (NYMS), en dyr, privat internatskola med militär disciplin och strikta regler, dit Donalds far hade skickat sin son när han var tretton år gammal. Detta efter att unge Trump hade gett sin musiklärare en blåtira ”jag gillade inte hans musiksmak” och tillsammans med sitt gäng rest in till Manhattan för att köpa stiletter så de kunde angripa ett granngäng.

Trump berättade senare att skolan knappast varit "en kärleksfull miljö", men eftersom han "var tvungen att slå tillbaka hela tiden" blev han en tuff kille och kom att uppskatta sin far, som han beundrande beskriver som sin förebild. En målmedveten man som lärde sin son att slå tillbaka för att vinna respekt. Ett uttalande som kan ha samband med Trumps litterära favoritcitat. Han fick en gång frågan vad som gripit honom mest i hans "favoritbok" Bibeln. Vi det tillfället kunde Trump inte finna ett ordentligt svar, men efter en tid återkom han med ett favoritcitat:

Men om olycka sker, skall liv givas för liv, öga för öga, tand för tand, hand för hand, fot för fot, brännskada för brännskada, sår för sår, blånad för blånad.

Tillbaka till Megyn Kelly, som i sin bok berättar att sex månader innan Donald Trump meddelade att han avsåg att ställa upp som presidentkandidat, började kontakta henne och sände inbjudningar till sin Florida resort. Kelly understryker att detta enbart var en av otaliga historier om 2016 års kampanj, att hon långt ifrån varit den enda journalist som Trump erbjudit gåvor och förmåner i utbyte mot positiv rapportering.

Dessutom avslöjar Kelly att chauvinistiska machoframtoningen som Trump excellerar i även tycks vara vanlig bakom kulisserna på Fox Channel, inte minst hos den nyligen avgående företagsledaren Roger Ailes:

Jag kunde kallas in till Rogers kontor, han stängde dörren och under den närmaste timmen eller två ägnade han sig åt en slags katt-och-råtta-lek som pendlade mellan besvärande sexuellt laddade kommentarer (t.ex. "vilken sexig behå" jag måste ha och hur gärna han skulle vilja se mig i dem) och legitim, professionell rådgivning. [...] I januari 2006, ringde Roger mig och bad mig komma upp till New York, vi hade ett chockerande möte [...] Han passerade gränsen och försökte flera gånger hålla fast mig och kyssa mig på läpparna. [...] Hans kontor var stort och det var inte lätt för mig att ta mig till den stängda dörren. När jag lyckades slita mig lös följde han efter mig och frågade illavarslande: "När går ditt kontrakt ut?"

Efter det att Gretchen Carlson, före detta Miss America och programledare för Foxs morgonshow Fox & Friends, avtal löpt ut den 23 juni 2016 lämnade hon in en stämningsansökan mot Roger Ailes, i vilken hon åberopade sexuella trakasserier. Hennes modiga initiativ fick andra kvinnor, att anklaga sin chef för otillbörliga närmanden. Murdochkoncernen, Foxs ägare, fick nog, fruktade stora ersättningskrav och tvingade Roger Ailes att avgå.

Locket var av och trots sin rädsla att utsättas för olika former av repressalier och mista sina jobb avslöjade nu fler kvinnliga anställda inom Fox Channel att de kontinuerligt utsätts för sexuella trakasserier från chauvinistiska kollegor. Inte minst har upprepade anklagelser riktats mot Donald Trumps kompis, den beryktade och mycket inflytelserika Bill O'Reilly, självutnämnd upprätthållare av amerikansk moral.

Redan 2004 stämdes O'Reilly av Fox Channel producenten Andrea Mackris för middagsinbjudningar och telefonsamtal som hon beskrev som oanständiga, liderliga och hotfulla. Tvisten bilades för miljontals dollar O'Reilly verkar dock vara oförbätterlig. Andrea Tantaros, vars välsvarvade ben kan beundras i Foxproduktioner som Outnumbered och The Five konstaterade nyligen att:

Fox News framställer sig som försvarare av traditionella familjevärderingar, men bakom kulisserna fungerar kanalen som en sexfixerad Playboy Mansion liknande kult, genomsyrad av hotelser, oanständigheter och kvinnoförakt.

Hon fortsätter sin harang genom att beskriva ovälkomna närmanden från olika Fox News gäster och inte minst det skrämmande beteendet hos män som Roger Ailes och Bill O'Reilly. Andrea Tantaros hävdar att den senare bad henne besöka honom på hans herrgård på Long Island där de skulle kunna umgås "mycket privat". O´Reilly konstaterade vid flera tillfällen att han att han förstod att hon var "en vild flicka", och att hon hade en "vild sida." Fox Channels reaktion på avslöjandena var att Tantaros inte längre skulle medverka i The O'Reilly Factor.

Andrea Tantaros hävdar vidare att hon efter sina avslöjande har blivit föremål för flera förtalskampanjer och varnar att för unga kvinnor är Fox Channel en skadlig, fördomsfull och trångsynt miljö att vistas i. Som ett exempel på den råa ton som råder hänvisade Andrea till den nu avsatte VD:n Roger Ailes yttrande om Los Angeles förre biträdande åklagare och populära Foxprofil, Kimberly Ann Guilfoyle, som "den där puertoricanska horan".

Det är möjligt att dessa damer har en agenda som går ut på att skada sina dugliga manliga kollegor och skaffa sig rikt tilltagna skadestånd. Men det finner jag högst osannolikt med tanke på de risker de löper och den rådande mediekulturen i USA och eventuellt runt om i världen, något som förmodligen kommer att bli ännu mer uttalat när en självdeklarerad bock som Donald Trump tar över rodret för världens mäktigaste nation. Som den lysande komikern John Oliver observerade:

Det visar sig att istället för att kunna säga till våra döttrar att de en dag kan bli presidenter för Amerika, så har det nu blivit uppenbart att ingen morfar kan vara alltför rasistiskt för att bli ledare för den fria världen.

Trump spelar upp sin mediokra teater för media och likt hypnotiserade ormar slingrar sig de mansdominerade TVstationernas och tidningsredaktionernas divor inför hans tongångar. På hans begäran dyker de upp i Trump Tower och i strid med all pressetik lovar de att hålla tyst efter att ha blivit tillrättavisade och förelästa om sina uppgifter av den Högste Ledaren. Och efter detta pressens förnedrande knäfall försätter medlöpare, överlöpare och lismare att köa för att få tillträde till den kommande presidenten och inför honom tigga om en plats i skuggan av den självförgudade monarken.

Nu älskar Paul Ryan mig, Mitch McConnell älskar mig, det är fantastiskt hur en seger kan förändra allt!

Efter att ha tillbringat en morgon med dessa ögontjänare och hycklare ödmjukade sig Den Store att besöka The New York Times, en av de mediajättar som inte förödmjukat sig genom att sända någon företrädare till Trump Tower.

Och vad hände där? Trump hälsades med underdånig respekt, tilläts exponera sitt svammel och ge undvikande, till intet förpliktigande svar: "Jag kommer att sätta mig in i det". Oemotsagd avslöjade han sina konstitutionsvidriga avsikter: "Teoretiskt sett kan jag driva min affärsverksamhet och även styra landet perfekt. Det har aldrig varit ett fall som detta." Det råder föga tvivel om att det Donald Trump har för avsikt att använda sitt presidentskap inte enbart för att tillfredsställa sitt ego, utan även för att främja sina ekonomiska intressen: "Det är braaaa att vara president!"

Låt mannen tala för sig själv och lyssna noga. Detta är efter det att Donald Trump i The New York Times högkvarter fått frågan om det stämmer att han som President-Elect sammanträffat med Nigel Farage, ledare UK Independence Party (UKIP) och bett honom att hjälpa honom i kampen mot ett vindkraftsprojekt i närheten av hans Aberdeenshire Golf Resort i Skottland. Var inte det en indikation om att Trump inte skulle kunna avhålla sig från att blanda nationellt ledarskap med personliga affärsintressen, liksom ett förakt för icke-fossila energikällor?

Min farbror var under 35 år professor vid M.I.T. Han var en stor ingenjör, vetenskapsman. Han var en bra kille. Och han var ... en lång tid sedan hade han känslor - det var länge sedan - han hade känslor i den här frågan. Det är en mycket komplicerad fråga. Jag är inte säker om någon någonsin verkligen kommer att veta vad det rör sig om. Jag vet att vi har, de säger att de har vetenskapen på sin sida, men då har de också de där fruktansvärda e-postmeddelandena som skickades mellan forskarna. Var var det, i Genève eller någonstans, för fem år sedan? Fruktansvärt. Där blev de avslöjade, förstår ni, så ni ser det och ni säger, vad handlar det här om. Jag har absolut ett öppet sinne. Jag kommer att säga er detta: Ren luft är livsviktigt. Rent vatten, kristallklart vatten är livsviktigt. Säkerhet är livsviktigt. Varumärket är givetvis ett hetare varumärke än det var tidigare. Jag kan inte hjälpa det, men jag bryr mig inte. Jag sa på 60 Minutes: Jag bryr mig inte. Eftersom det inte spelar någon roll. Det enda som är viktigt för mig är att styra vårt land. De är gjorda av enorma mängder stål, som går in i atmosfären, oavsett om det är i vårt land eller inte, går det in i atmosfären. Vindkraftverk dödar fåglar och vindkraftverk behöver massiva subventioner. Med andra ord, vi subventionerar vindkraftverk över hela landet. Jag menar, för det mesta fungerar de inte. Jag tror inte att de skulle fungera alls utan subventionerna, och det oroar mig, och de dödar alla fåglar. Ta ett vindkraftverk, ni vet i Kalifornien har de, vad är det? Kungsörn? Och de är som, om de skjuter en kungsörn, hamnar de i fängelse i fem år och ändå dödar de dem med, de måste faktiskt skaffa tillstånd att de endast är tillåtna att döda 30 eller något sånt på ett år. Vindkraftverk är förödande för fågelbeståndet, O.K.

På mig ger det där intryck av att vara en dåres rappakalja, även om en och annan hoppfull agnostiker kan mumla: "Låt oss ge killen en chans". Ett tanklöst yttrande, som den sarkastiske John Oliver påpekade:

En Klan-stödd kvinnoföraktare och internättroll kommer att hålla nästa Regeringsdeklaration. Det är inte normalt. Det är rent åt helvete!

Att lita på en sådan person är som:

att befinna sig i ett flygplan och finna att vår pilot är en vombat. Jag gillar inte det här, jag förstår inte hur det hände och jag är ganska säker på att vi är på väg mot en katastrof, men va´ fan, kom igen dårputte - bevisa att jag har fel!

Brenner, Marie (1990) “After the Gold Rush,” i Vanity Fair, September. Hitler, Adolf (1970) Mein Kampf. Stockholm: Askild & Kärnekull. Hochman, David (2004) “The Playboy Interview: Donald Trump,” i Playboy, October. Kelly, Megyn (2016) Settle for More. New York: Harper. Kunzru, Hari (2016) “Trump and Me by Mark Singer review – a lot of laughs but then horror,” i The Guardian, 21 July. Lasch, Cristopher (1997) Den narcissistiska kulturen. Stockholm: Norstedts/Panter. Mayer, Jane (2016) “Donald Trump´s Ghostwriter Tells All,” i The New Yorker, July 25. Plaskin, Glenn (1990) “The Playboy Interview: Donald Trump,” i Playboy, March. Singer, Mark (1997) “Trump Solo,” i The New Yorker, May 19.

Donald Trump´s New York Times Interview: Full Transcript. 23 November 2016 (online):

https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/23/us/politics/trump-new-york-times-interview-transcript.html

John Oliver: Trump Wins Election, Last Week Tonight,14 November [online]:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a3vltFa2PhY

Why do humans fight?

Why all the copious blood?

Can letting blood be right,

since hubris makes it flow in the mud?

Came to think of the Swedish vaudeville writer Emil Norlander´s poignant tune from 1915 and have been humming it after I a week ago began to sense that the year is drawing to an end and that I soon, like Mayakovsky, reluctantly once again would experience how:

the evening

turned its back on the windows

and plunged into grim night, scowling

Decemberish.

Gloominess threatens many of us, especially if we feel that not everything turns out according to our wishful thinking. Even if we do not like to admit it, we might even wonder why God has not favoured us more than he has done. A shabby query, especially when it comes from a privileged man like me. Someone who has so much to be thankful for. Such a complaint is both pathetic and shameful if contrasted with the torment of all those who suffered/suffer so much more than I have ever done. The hopeless, raw agony in solitary confinement and death camps, the despair in out-bombed cities, among disease, starvation and abandonment.

While I wrote this, Trump won the election in the US. Unfortunately I had suspected such an outcome, but how could it even be possible? I feel numb, nauseated. The election of that man is likely to turn out to be a disaster, no matter what political views you might have. Some people assume Trump won in accordance with God's will. A few days ago I was through the TV confronted with an elderly American lady who told us:

- Every morning and evening I go down on my knees and pray to God that Donald Trump will win.

Did God comply with the old lady´s prayer? Is there really such a thing as divine justice? Several of my friends have been stricken by cancer, with all it implies of fear of death and excruciating pain. And what is worse, given our sense of justice - they have all been and are benevolent, vibrant and beautiful women, who have given much to their fellow human beings, especially me. They are and were much better persons than I ever will be. I who so far have been spared any major ailments.

The ancient theodicy problem - the so far unanswered question why evil, stupidity and suffering subsist everywhere, and at all times. The cold and merciless violence. How can someone under such circumstances explain the faith in the existence of a caring and loving God?

Already in the early 300's, a certain Lactantius wrote a well-formulated text about God's anger. Lactantius was a well-read and erudite advisor to Constantine the Great. His views and crisp explanations of the Christian faith have had a great importance for posterity. In his writings Lactantius took up the issue of the presence of evil in God's creation. To give relief to his opinions, he quoted a variety of ancient philosophers, among them Epicurus.

There are only fragments left of Epicurus's writings, but these are interesting and his followers praised him as a wise, modest and friendly man. During his last years Epicurus was stricken by a painful disease. In a letter to a friend he noted: "I have been attacked by a painful inability to urinate, and also dysentery, so violent that nothing can be added to the violence of my sufferings." Nevertheless, he claimed that he was going to die satisfied: "the cheerfulness of my mind, which comes from the recollection of all my philosophical contemplation, counterbalances all these afflictions."

Much of Epicurus teachings were collected by Diogenes Laertius hundreds of years after the great philosopher´s death and furthermore excellently depicted in Lucretius´s (99 – 55 BC) poem On the Nature of Things.

Several of Epicurus thoughts revolved around the question of how it was possible that almighty gods could accept evil and suffering. Epicurus, who lived 300 BC, believed that "gods" existed, but to him they were a personifications of impersonal forces that control and keep the Universe united. To imagine a God as a being with human characteristics would, according to Epicurus cause painful doubts. Thoughtlessly submitting to the belief in a benevolent God would be tantamount to denying our human intellect and obliterate the joys brought about by curiosity. If we believed that all natural phenomena were controlled by a benevolent God who took care of everything – why bother to study natural phenomena, why try to improve anything?

Lactantius description of Epicurus's doubts about the existence of a merciful becomes an excellent summary of the theodicy problem:

God, he says [Epicurus], either wishes to take away evils, and is unable; or He is able and is unwilling; or He is neither willing nor able, or He is both willing and able. If He is willing and is unable, He is feeble, which is not in accordance with the character of God; if He is able and unwilling, He is envious, which is equally at variance with God; if He is neither willing or able, He is both envious and feeble, and therefore not God; if He is both willing and able, which alone is suitable to God, from what source then are evils or why does He not remove them? I know that many of the philosophers, who defend providence, are accustomed to be disturbed by this argument, and are almost driven against their will to admit that God takes no interest in anything, which Epicurus especially aims at.

Can a Father of the Church really present such a blatant challenge to the omnipotence of God, even if he hides behind a pagan philosopher? Eventually, Lactantius made an attempt to rescue the belief in the goodness of God by claiming that if evil did not exist, we would not be able to know what goodness was. We would be like animals, completely unaware of the presence of God in his creation. Without evil we would not have any reason to seek God´s protection and support. He wants to be loved and to love and humans must thus be endowed with free will. Without a personal choices love cannot exist.

That there are no choices without evil is an argument that often has been used in Christianity and then with reference to Genesis, in which the first humans by eating the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge were challenged by the choice to love themselves and thus rely on their own abilities, or instead rely on God's power and benevolence. By presenting humans with a choice the serpent in Eden´s Garden was actually a servant of God:

Now the serpent was more crafty than any of the wild animals the Lord God had made. He said to the woman, “Did God really say, ‘You must not eat from any tree in the garden’?” The woman said to the serpent, “We may eat fruit from the trees in the garden, but God did say, ‘You must not eat fruit from the tree that is in the middle of the garden, and you must not touch it, or you will die.’” “You will not certainly die,” the serpent said to the woman. “For God knows that when you eat from it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.”

Lactantius added urgency to this argument by arguing that the Final Judgment would soon come. Accordingly, Christians had no time to squabble whether God was good or evil. Their only chance for salvation would be an unconditional belief in God´s omnipotence. As Paul wrote in his first letter to the Corinthians:

When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known. For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.

Jesus was also asked why God did not wipe out evil from his creation and like Lactantius he replied that all we could do was to wait for the Last Judgement:

Because while you are pulling the weeds, you may uproot the wheat with them. Let both grow together until the harvest. At that time I will tell the harvesters: First collect the weeds and tie them in bundles to be burned; then gather the wheat and bring it into my barn.'" (Mat 13: 29-30).

Perhaps Jesus' words reflected a perception common among Jews at the time - brooding about evil´s presence could not affect God's omnipotence. In Judaism and Islam, theories about the presence of evil in God's creation do generally speaking not occupy much space. If a believer accepts the all-powerfulness of God, it is quite enough to lead a righteous life according to religious practices and regulations. Of course, there are quite a lot exceptions from such a claim. Within the folds of both Judaism and Islam we find several writers and theologians who have pondered about evil and suffering. Among the Muslims, Sufis have been particularly occupied with the theodicy problem.

al-Qurʾān mentions Iblis, the Devil, as an opponent of God. Nevertheless, he is subordinate to Him. Iblis is the epitome of arrogance, megalomania based on self-assertion. An excessive appreciation of one´s own power and ability. The name Iblis is generally interpreted as "he who causes despair." Believing oneself to be better than other creatures, or even equal to God, leads to isolation and loneliness. A power-hungry man isolates himself from others, from the creation and human community.

Iblis is "whispering into the hearts" and make us doubt everything, except our own righteousness. Iblis is the voice of egoism, an exaggerated belief in our own superiority. When God ordered all creatures to kneel before Adam, Iblis refused to do it. He saw only the clay God had used to create man and could not perceive the divine breath that had given him life. Similarly, egoists cannot distinguish the divine soul life they share with other people. They only value what they can acquire from their fellow-beings.

Sufism can be considered as a systematic exercise to gain to self-knowledge, both through practical training and teaching from a wali, a custodian. The Sufis wanted to look beyond the material world and find what they called the Ultimate Reality. Like many other Sufis, Abu Hamed Al-Ghazzali (1058 -1111 AD) searched for a method to unify the pious soul with God. In his book The Alchemy of Happiness, in Farsi - Kimiya-yi Sa'ādat, Al-Ghazzali explained why devout Muslims must adhere to Islam's commandments and regulations, if they do so they become capable to seek God within their inner self and eventually encounter a love beyond good and evil . By purifying our mind and come to realize that love is God's true essence, we enable ourselves to open up our consciousness. Al-Ghazzali´s message appears to be reminiscent of the words of Jesus: "Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them” (Matt. 5:17). The ´Sufi poet Rumi (1207-1273) compared the realization of God's omnipotence with the search for love:

The minute I heard my first love story

I started looking for you, not knowing

How blind that was.

Lovers don´t finally meet somewhere.

They´re in each other all along.

To translate Al-Ghazzali´s text as Alchemy of Happiness may be misleading, Science of Happiness might be closer to its actual meaning. For Al-Ghazzali "alchemy" was synonymous with awareness of Cosmos as a manifestation of God - that nothing can exist outside of God. The word al-kīmiyā orginates from the Greek χημία a name for Egypt, from the Egyptian word khmi, meaning "black soil". Kīmiyā thus has to do with life, with plants sprouting from the black, fertile soil.

Ancient Greeks associated emerging life to Egyptians' assumed ability to create life by using heka, a concept meaning “to activate the life force”, like the energy that makes organic plants sprout from the dead soil. The Greek χημία was originally a term for the study of the properties of water as a source for growth; a life-giving power. Only later did the term come to mean magic, in the sense of using supernatural forces for practical purposes. Since the word was linked to "the black", χημία soon came to mean magic used for evil purposes - "black magic".

By using the word alchemy Al-Ghazzali presumably indicated that through knowledge of the world's true nature, i.e. its absolute conformity with God, you may attain communion with the divine. Sufis based their teaching on a notion that practice and teaching were means to seek God in your interior. For example, they could use the Quranic text about the conflict between the sons of Adam - Cain and Abel. Blinded by his jealousy Cain could not realize that both he and his brother were endowed with God's spirit. An ignorance that made Cain bring evil into God's creation. Both Cain and Abel worshiped God, but Cain had the perception that God favoured his brother more than him. This suspicion about God's injustice nurtured Cain's hatred:

Recite to them the true story of the two sons of Adam, when they offered a sacrifice and it was accepted from one of them but not from the other. He said: "I will slay you!" The other replied: "God only accepts from the devout. Were you to stretch forward your hand to kill me, I shall not stretch forth my hand to kill you, for I fear God, Lord of the worlds. I want you to bear my sin and yours, and thus become a denizen of the Fire, for this is the reward of wrongdoers." […] It is for this reason that We decreed to the Children of Israel that he who kills a soul neither in revenge for another, nor to prevent to prevent corruption on earth, it is as if he killed the whole mankind; whereas he who saves a soul, it is as if he had saved the whole of mankind. Our messengers came to them bearing clear proofs, but many of them thereafter were disobedient on earth (The Qur´an 5:27 – 32).

According to The Qur´an, we have every right to defend ourselves against injustice and violence, but Abel chose not to defend himself from the fury of his nefarious brother. Consequently, Abel did not rebel againsGod´s design for a perfect world. By allowing Cain´s sin to punish itself, Abel abided to high morals. According to the Sufis, Abel´s refusal to defend himself was an acknowledgement of God´s divine will. By not using force Abel left it to God to pass judgement on his brother, thus subjecting himself to God´s superior command. By disciplining themselves by following what they believed to be the rules of God, which also are the rules of the Universe, the Sufis are adapting themselves to a behaviour they believe is pleasing to God. An inability to quench anger and endure evil is accordingly a sign of a flawed belief in God's omnipotence.

That the world is an integral part of God is also an important ingredient in the mystical direction of Judaism called Kabbalah, “receiving/tradition”. Like the Sufis, Kabbalists devote themselves to an intensive study of the world around them, at the same as they pursue a union with God. Both faiths are confronting the problem of the presence of evil in God´s creation. However, Kabbalists claim even stronger than the Sufis the importance of free will.

According to Kabbalists, God has hidden himself from his creation, though we may seek Him through the Sefirot, evidences of Eyn Sof, Infinity, one of God´s manifestations. Sefirot means "radiance" or "outflow" and may be considered as some kind of "sparks" of the Divine. If combined into a unity the Sefirot may bring us closer to God. Among the ten Seifirot, we find concepts like wisdom, compassion, beauty and understanding. By applying them to our own existence we may approach God. Kabbalah and Sufism both require discipline and love.

Perhaps the most complex Kabbalah tradition, but also a sophisticated description of the origin of evil is found in Isac Luria´s (1534 - 1572) theories. Since Luria lived and worked in Tzfat in Palestine under the Ottoman Empire, it is not impossible that he developed his ideas with awareness of the Sufi system.

In the beginning, according to Luria, God encompassed everything. Like the Brahma of the Hindus "he rested in himself." However, he was endowed with a desire to create, an act that requires movement. Empty/open space is a prerequisite for mobility and to that end God, Ein Sof, had to tighten/narrow himself and the emptiness that thus was created is called Khalal Hapanu a kind of abyss inhabited by us humans.

God exists, we are surrounded by him. He is infinite, but He has consigned us to emptiness so we may seek him in it. Our quest is what makes us human. We are lost in the void and need to find a way out, the solution is found in love and care for others. Compassion fills the void, it creates togetherness. For guidance, we have the Sefirot, the sparks of divine presence we find in the Holy Scriptures and within ourselves and others.

The Kabbalist calls wisdom Naham D'kissufa, Bread of Shame, an awareness of our own shortcomings and sins makes us attentive to the needs and gifts of others. God´s absence makes us aware of our own inadequacy. To move out of emptiness, out of Khalal Hapanu, we need the support of others and faith in God. Love and compassion guide us out of desolation and lead us to the warmth of God. It is our will, faith and pursuit of the good that saves us. Evil abides in emptiness, love is found in community. As the last words in Dante´s Divina Commedia assure us - l'amor che move i sole e l'altre stele, “the love that moves the sun and the other stars”.

In his fantastic tale The Snow Queen H. C. Andersen turned around Kabbalah´s world view. The brilliant shards that had been spread out in the world turn by Andersen into reflections of evil, contrary to the Sefirot, which emanate goodness.

H.C. Andersen begins his tale by telling how a goblin, "one of the worst; he was the Devil” one day, when he was in a really good mood, made himself a mirror:

that had the power to make everything good and beautiful that was reflected in it shrink to almost nothing, while whatever that was worthless and loathsome would stand out clearly and looked even worse. In the mirror the loveliest landscape looked like boiled spinach, and the best people turned beastly or stood on their heads with no stomachs. Their faces became so distorted that they were beyond recognition, and if you had a freckle, you could be sure it would spread over your nose and mouth. That was excellent fun, said the Devil. If a good, pious thought passed through someone´s mind, a smirk would appear in the mirror, and the troll demon would have to laugh at his ingenious invention.

Together with the small devils, who went to the Devil´s "troll school", he went around the world and made people reflect themselves and their surroundings in the evil, magic mirror, so they received a distorted view of everything and became unable to agree on anything. They began fighting and arguing, something the Devil found terribly funny.

The Evil One got the brilliant idea that he and his little devils could fly up to heaven to have God and His angels reflect themselves in it. Then everything would turn to chaos, something the Devil always strived for. However, on the way up there the mirror began to tremble in the hands of the devils. They dropped it and when it fell to earth it split" into a hundred million billion pieces and more."

Some shards were smaller than grains of sand, and whirled around in the air. If such a minuscule glass grain ended up in the eye of someone, her/his sight became distorted and the victims could only percieve disgust and misery. Some mirror pieces were so large that they were as window glass, especially among wealthy people and in places where judgement was passed, like castles and courtrooms. Other sheets of glass were used for eyeglasses. Each glass fragment retained its capacity to distort, pervert and make reality worse. The vilest thing that could happen was if a small grain of magical mirror glass sneaked into your body and reached the heart, because the heart was then turned into an icicle.

While reading H.C. Andersen´s tale I came to think of Benedict Spinoza (1632 - 1677), who earned his living by grinding optical glass, which led to a premature death from consumption. The quartz dust was stored in Spinoza's lungs, which could not get rid of it but instead had to encapsulate it in scar tissue, until nodules and inflammation killed him. That glass killed Spinoza may perhaps be considered as a symbol of his philosophy. The optical glass he cut did, unlike Andersen's magic glass, enable people to see better. Spinoza was undeniably very perceptive and he looked at life in a different manner than most of his fellow beings. The glass became part of Spinoza body and may thus be related to his thoughts. Spinoza saw no distinction between dead matter, body and soul, they were just different aspects of the same reality.

Spinoza argued that everything that exists, the whole universe, is controlled by an eternally defined set of rules. God and nature are just two names for the same reality. Creation consists of smaller units that find themselves in different, constantly changing positions, driven by cause and effect. Everything is part of an indivisible whole. God exists and all matter are parts of God, something that is reminiscent of basic ideas within Islam and Judaism.

Since everything is connected, any explanation is limited to smaller entities and relationships within an incomprehensibly large and all-inclusive system - God/Universe. Politics and science are concerned with external acts and circumstances, while religion cannot be explained, not circumscribed by dogmatic thinking and regulations. What really matters is love, righteousness and devotion to God, i.e. the things we experience through our emotions.

Goodness is what we perceive as well-intentioned and joyful, that which benefits laetitia, joy and contentment, while its opposite, tristitia, sorrow and evil, reduces the soul´s vitality. What Spinoza calls ethics is our common quest for what we feel is best both for ourselves and others, and not least the nature that surrounds us and which we all depend upon. Everything is connected – the material, organic and spiritual spheres are not separated.

Of course the tolerant and perceptive Spinoza came under fierce attack from all quarters; from Jews and Christians, theologians, politicians and scientists. Nevertheless, he was proposed a professorship at the University of Heidelberg, but did not accept the offer since he believed that it would circumscribe his possibilities to express his thoughts in an “unbridled” manner.

Spinoza's writings were placed on the Catholic Church's index of prohibited and harmful books. Already at the age of 23, before he had published anything, Spinoza was placed in cherem, meaning he was cursed by the Council of Elders of the Jewish community in Amsterdam and expelled from the congregation. The cherem is preserved, but not any documents describing the court proceedings that resulted in a curse. It is however clear that the Elders found him guilty of questioning the divine origin of the Laws given to Moses. In addition, Spinoza regarded God as an abstraction and not as an individual, redemptive entity. The formulation of the cherem was relentless:

Cursed be he by day and cursed be he by night; cursed be he when he lies down, and cursed be he when he rises up; cursed be he when he goes out, and cursed be he when he comes in. The Lord will not spare him; the anger and wrath of the Lord will rage against this man, and bring upon him all the curses which are written in this book, and the Lord will blot out his name from under heaven, and the Lord will separate him to his injury from all the tribes of Israel with all the curses of the covenant, which are written in the Book of the Law. But you who cleave unto the Lord God are all alive this day. We order that no one should communicate with him orally or in writing, or show him any favour, or stay with him under the same roof, or within four ells [2 metres] of him, or read anything composed or written by him.

Spinoza was condemned trough a Beth Din, a Hebrew word meaning “Judgment House”. From the beginning, it was an actual abode where rabbis met to pass judgement on those who had violated religious laws and regulations. Over time Beth Din turned into a concept, a kind of legal discussion between the theologians, who presented arguments for or against an accusation. Elie Wiesel wrote a play about a Beth Din where the accused is no less than God Himself - The Trial of God (as it was held on February 25, 1649, in Shamgorod).

The play is written as a Purimschpil, a kind of comedy, almost like a Commedia dell´Arte, which during Purim celebrations was performed by traveling theatre groups in Yiddish speaking villages of Ukraine, Poland and Russia. Purim is a cheerful feast celebrated in memory of the Jewish heroine Esther who saved her people from being massacred by the evil king, Haman. I have read somewhere that Wiesel's piece is not regarded as a major masterpiece, but when I got hold of it, I found it was a quite interesting drama - fast-paced and vibrant. I find it surprising that it is not performed more often.

.jpg)

The story, in brief, deals with three Purimschpilers, wandering actors, who in the winter of 1649 arrives in a shtetel, a small town in Ukraine, named Shamgorod. They seek out the inn and offers the innkeeper the performance of a Purimschpil in exchange for food, drink and shelter. The innkeeper becomes angry and upset. How can a group of ragged comedians imagine would be proper to perform a farce in a city where only last year Khmelnytsky´s Cossack hordes had slaughtered all the Jews, except the innkeeper and his daughter, who had never returned to her own self after being raped? Nevertheless, the actors insist, they are starved and frozen and the innkeeper gives in to their pleading. He will allow them to perform their comedy, though on the precondition that he choose the theme for the play. The Purimschpilers accept his condition and their host insists that they perform a Beth Din where the accused will be no one less than God himself. The innkeeper, Berish, is going to act as prosecutor, the three actors will be judges, the Christian maid Maria and the host's daughter will bear witness about the cruelties that had been performed in God´s name and sanctioned by Him. An Orthodox priest will be audience, with permission to interrupt the act with his comments.

The performance obtains a sinister backdrop when the priest, a plump bon viveur who aspire for free food and drinks, discloses that he has heard that the small town is being threatened by a new pogrom. There are anti-Semites waiting to join forces with the Cossacks to assassinate Berish, his daughter and the Christian maid who lives with them. They will certainly also kill the three actors. Berish explains that he has already lost everything he loved and before he dies he wants to accuse God for the cruelty and injustice he has inflicted on his people. The priest is taken aback by Berish´s fierceness. Despite the priest´s intention to save Berish and his daughter he is deep in his heart a convinced anti-Semite who regards all Jews as Christ-killers. Berish suspects that the priest's warnings of an impending massacre may be a trick to have an opportunity to baptize him and his daughter.

Before the performance begins the participants cannot agree about who will defend God. Then Sam appears. A handsome, eloquent stranger with great knowledge of Jewish faith and law. According to Wiesel's stage directions:

SAM, the STRANGER. Intelligent, cynical, extremely courteous. Diabolical. His age? Still young. Neat, almost elegant.

Where does Sam come in? His name stands out from the others on the list of the dramatis personae. It is neither a Jewish, nor a gentile name. He may be a Jew, though he seems to have good contacts with the gentiles. The Christian waitress Maria knows who he is. She has had earlier bad experiences with him, though no other of those present knows Sam. The stranger accepts the role as God´s defender.

Sam explains that since God has given us a free will, we are allowed to question his actions. We can demand explanations and motives from God. However, because He does not answer directly tour questions, we need to seek God in the inner voice we find deep within us. Sam claims that God desires the good. We would all be better off if we helped and loved each other. The presence of evil and cruelty cannot be explained due to our limited understanding. We may blame God, but we cannot deny him, doing so would be to deny the existence of creation. It is a human duty to interpret the divine justice in such a way that it becomes the foundation of kindness and compassion.

Sam concludes his defence by declaring: "Endure. Accept. Say thank you and amen. Our task is to venerate and glorify God. To love him at all costs!" The three actors are deeply moved by Sam's speech and salute him as a performer of miracles, a rabbi, a teacher, one of the 37 Just who according to the Talmud are living on earth, a tzaddik.

However, Bashir's wrath does not diminish. Perhaps he suspects who Sam really is, something that Maria, the maid, knew all along, and which is underlined by Sam's own words:

I am not allowed to reveal myself to you. (In a low voice) And what if I told you that I am God's emissary? I visit His creation and bring stories back to Him. I watch all men. I cannot do all I want, but I can undo all things.

The priest once again warns that the killers are on the way - the actors, Bashir, and his daughter Maria have to flee. Bashir refuses to leave his inn before judgement has been passed on God:

I lived as a Jew, and it as a Jew that I shall die - and it is as Jew that, with my last breath, I shall shout my protest to God! And because the end is near, I shall shout louder. Because the end is near, I´ll tell Him that He´s more guilty than ever!

Sam laughs and reveals who he really is – he is the Devil:

So you took me for a saint, a Just? Me? How could you be that blind? How could you be that stupid? If you only knew.

We should have suspected the truth, even his name indicated it. Sam is a diminutive. In the Jewish tradition Samael is an angel of evil - the Devil. He lifts his arm as to give a sign, the candles are extinguished, darkness all around. We hear a horrifying, deafening roar.

The play is far more complicated than my summary suggests, filled with allusions to the omnipotence of God and man's submission to His will, in accordance with a variety of Jewish notions - especially the fact that Jews have been selected to be "God´s chosen people" and have no other choice than to accept his will, even if such a choice may involve great suffering. Acceptance of God´s omnipotence is not a choice for a Jew, if he denies God´s existence s/he ceases to be a Jew, and there is a risk that God will lack representation on earth. A Jew can thus accuse God for choosing her/him, but cannot deny God because that would mean denying her/his own existence. Wiesel had personally suffered all this agony. In the image below we see him in Auschwitz. It is Wiesel who, together with the emaciated man is not looking towards the photographer.

Elie Wiesel has stated that his play is based on an experience he had as a seventeen year old inmate of Auschwitz, where he witnessed how three Jewish rabbis in one of the camp barracks conducted a Beth Din against God. The Christian theologian Robert McAfee Brown has described the event in a preface to Wiesel's play:

The trial lasted several nights. Witnesses were heard, evidence was gathered, conclusions were drawn, all of which were issued finally in an unanimous verdict: the Lord God Almighty, Creator of Heaven and Earth, was found guilty of crimes against creation and humankind. And after what Wiesel described as an “infinity”, the Talmudic scholar looked at the sky and said “It´s time for evening prayers,” and the members of the tribunal recited Maariv, the evening service.

Maariv is the opening word in the shared Jewish evening prayers. Maariv is a verb connected with word erev, evening, and can be translated as "to advance the Night". The prayer is performed standing, with the participants facing Jerusalem, and led by a cantor who sings the Jewish creed Shema Yisreal: "Hear, O Israel, the Lord is your God, the Lord is one" and two hymns from the Psalms, one containing the words:

Yet he was merciful; he forgave their iniquities and did not destroy them. Time after time he restrained his anger and did not stir up his full wrath.

The hymns are followed by nineteen blessings proclaiming God's power and protection He bestows upon the people of Israel and then the Maariv ends with an "Amen".

Elie Wiesel's Night dealing with his experiences in Auschwitz and Buchenwald is profound and multifaceted. Wiesel, who died in July this year was the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize and known for his strong condemnation of massacres of Armenians, Cambodians, Bosnians, Rwandans, Sudanese, Native Americans and many others. However, like the figure of Sam in his play Elie Wiesel personality is difficult to grasp and understand. He was silent about the suffering of people he regarded as a threat to Israel.

Wiesel was member of Irgun, the National Military Organization, a paramilitary Zionist organization that between 1931 and 1948 battled Palestine Arabs and British institutions with terror. Wiesel was also an inveterate defender of Benjamin Netanyahu and his hostile Palestine policy. He criticized his friend Barack Obama for his view that Israeli settlements on Palestinian land ought to be withdrawn immediately. Wiesel furthermore propagated for the settlement organization Elad, which try to force Palestinians to leave Jerusalem. He defended the Israeli attacks on Gaza and as Chairman of the Trustees Council of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum he opposed, until his retirement in 1986, Roma people´s representation within the Museum. Few people are able to live up to their humanitarian ideals, unfortunately this applied to Elie Wiesel as well.

After my exposé of the theodicy problem I probably ought to declare my own faith. Due to my job as a teacher of history of religions I have often been asked whether if I believe in God. My answer is, strangely enough, an unreserved "yes". Does this mean that I can accept a God who permits evil and wrongdoing? To that question I must answer "no". How can I wriggle myself out of such a paradox?

My students tend to dislike my answers. They find them convoluted and elusive. Especially since my faith is far from being pragmatic. I do not at all believe that Joshua convinced God to make the sun stand still at Gibeon and the moon in the valley of Askalon, so he would have time enough to slaughter all of his enemies. Nor that sin entered the world because a woman invited her partner to eat a tasty fruit. I cannot agree with the reasoning that "it has only been one woman in history who gave birth to a child without having sex and that this is the reason for us worshipping her." However, such disbeliefs do not at all prevent me from believing in God and pray to him.