Blog

I live in a city and am surrounded by houses and people, though also by several gadgets; books, records, movies, TV and not least my computer. This is my little world, my environment, my habitat, and in general I like it here.

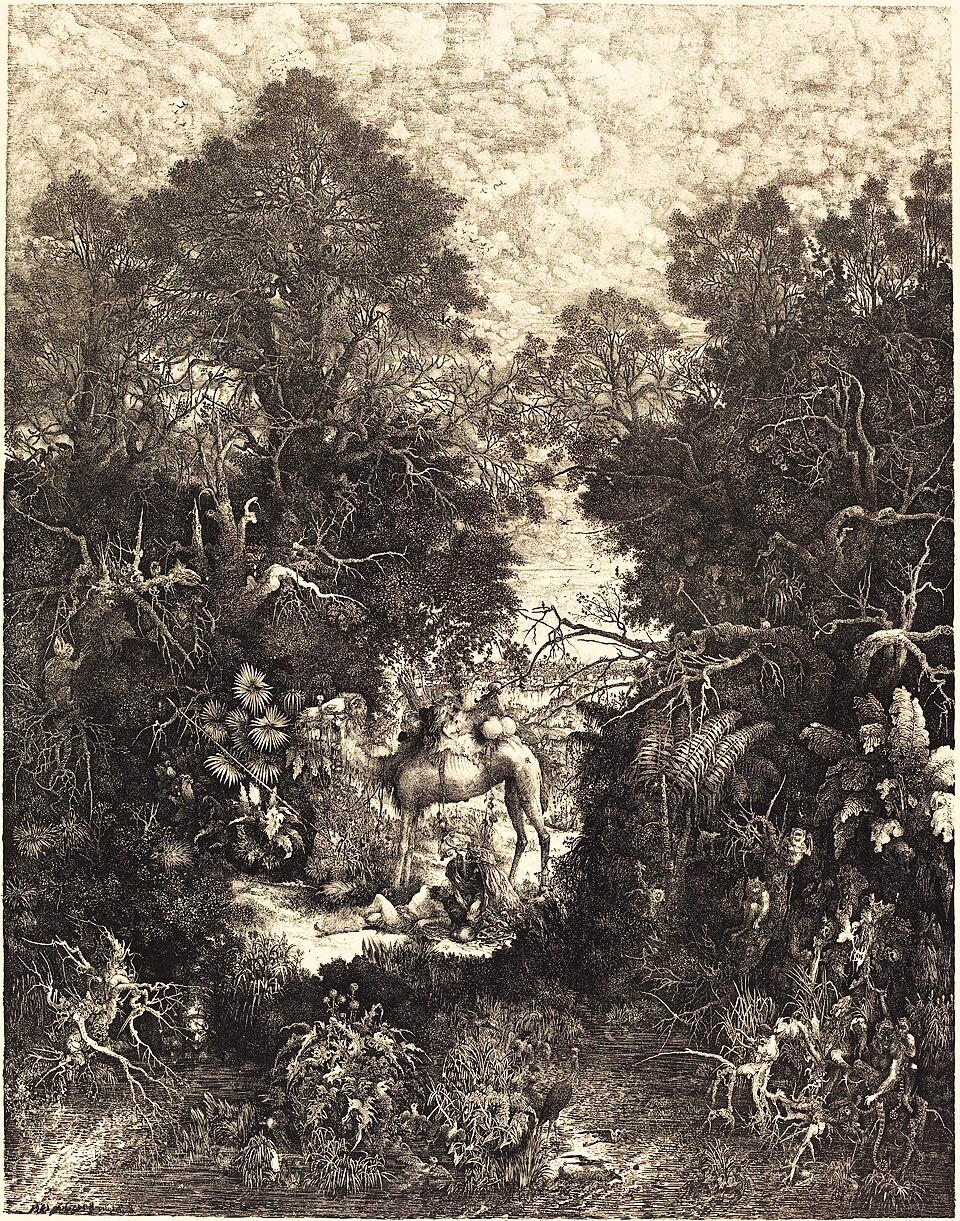

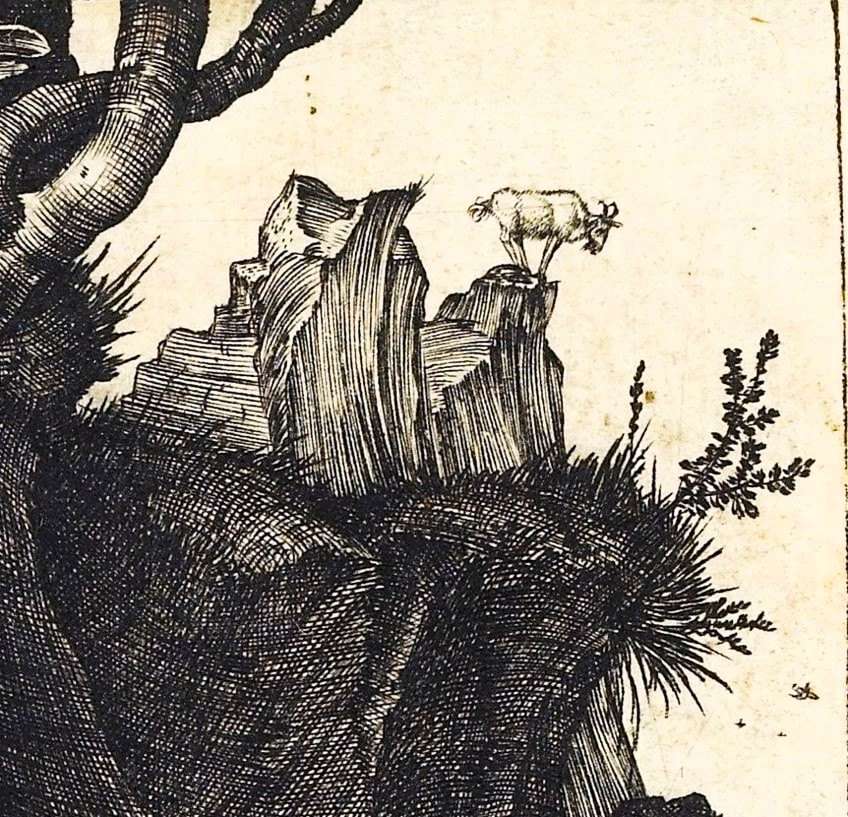

I also have the opportunity to change my habitat and might occasionally live by a tropical beach, or in a Swedish forest. In the latter case, during long walks, or while rowing on the nearby lake, I can let myself be absorbed by the powerful presence of nature; the smell of greenery and earth, the sky above my head, the surrounding birds and small animals.

It is now cold inside the house, very cold. It has been standing uninhabited for quite a long time and after the forest walk I huddle by the fireplace, in which I have put plenty of fire wood. Soon the fire is burning strong and hot and I do no longer care about the gloomy weather outside the window. I have randomly picked up a book from the shelf – Allan Watt's Nature, Man & Woman. It has been a very long time since I've read it, but already after a couple of pages it evokes a lot of thoughts.

Watts writes how we humans can enjoy and be enchanted by nature and what an enriching feeling it is to have received this gift. As in William Blake's wonderful poem, constantly repeated, but always remaining fresh and moving:

To see a world in a grain of sand

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand,

And eternity in an hour.

But, as Watts rightly states – the fish seen in the clear water, the bird hovering under the clear sky, do not experience the world and life as a mighty wonder:

We know that that the fish swim in constant fear of their lives, so as not to be seen, and dart into motion because they are just nerves, startled into a jump by the tiniest ghost of an alarm. We know that the “love of nature” is a sentimental fascination with surfaces – that the gulls do not float in the sky for delight but in watchful hunger for fish, that the golden bees do not dream in the lilies but call as routinely for honey as collection agents for rent, and that the squirrels romping, as is seems, freely and joyously through the branches , are juts frustrated little balls of appetite and fear.

Nevertheless – what a triumph to exist! To be human and feel like Blake did. To be enraptured by life. However, increasingly, we are caged in by a technocratic A.I.-generated world. Is it a condemnation, or a blessing? Like most things in life – maybe both. One thing is certain and that is that the world as we know it, our habitat, is changing and doing so at an incredible speed.

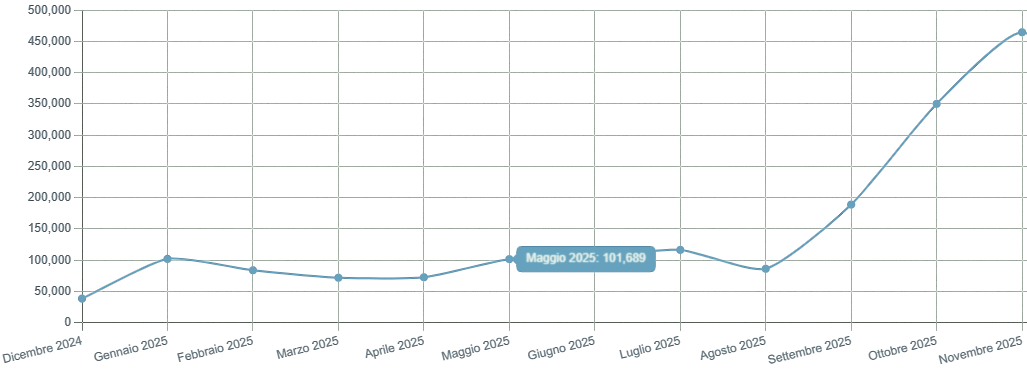

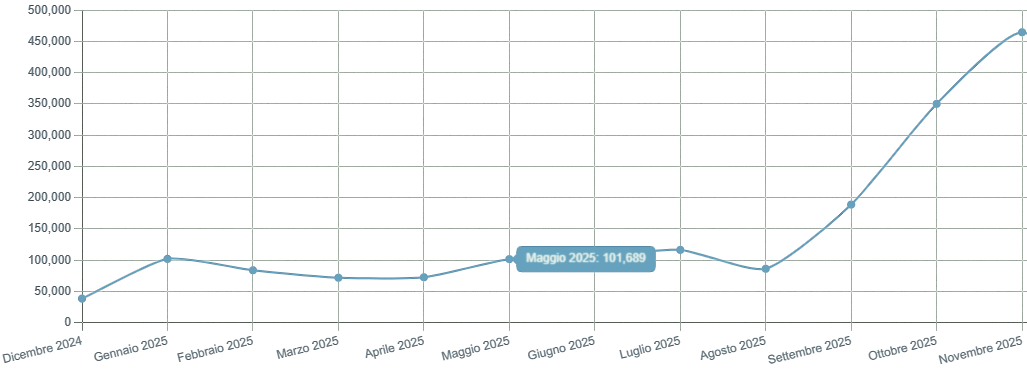

For several years, my blog posts have rarely attracted more than a maximum of five thousand visitors per day. Imagine my surprise when I a few months ago found that they had suddenly risen to between thirty and forty thousand visitors per day. What had happened?

With some satisfaction, even though I assume I am actually writing my blog posts for my own pleasure I have to admit that I was actually pleasantly surprised and imagined that I might have reached what some writers call the tipping point, namely that after years of strenuous effort you suddenly find that you are reaching an unexpected number of readers, something that in the book and entertainment industry might happen unexpectedly. The concept was popular about ten years ago, but I don't know if people still talk about it that much.

However, a friend of mine stated that the apparent and sudden rise of readers must be due to A.I., Artificial Intelligence – it was for certain unmanned search engines that harvested my insights to feed them into the global knowledge network that since the end of 2022 is gobbling up all conceivable information, probably even what could be found among my modest blog posts.

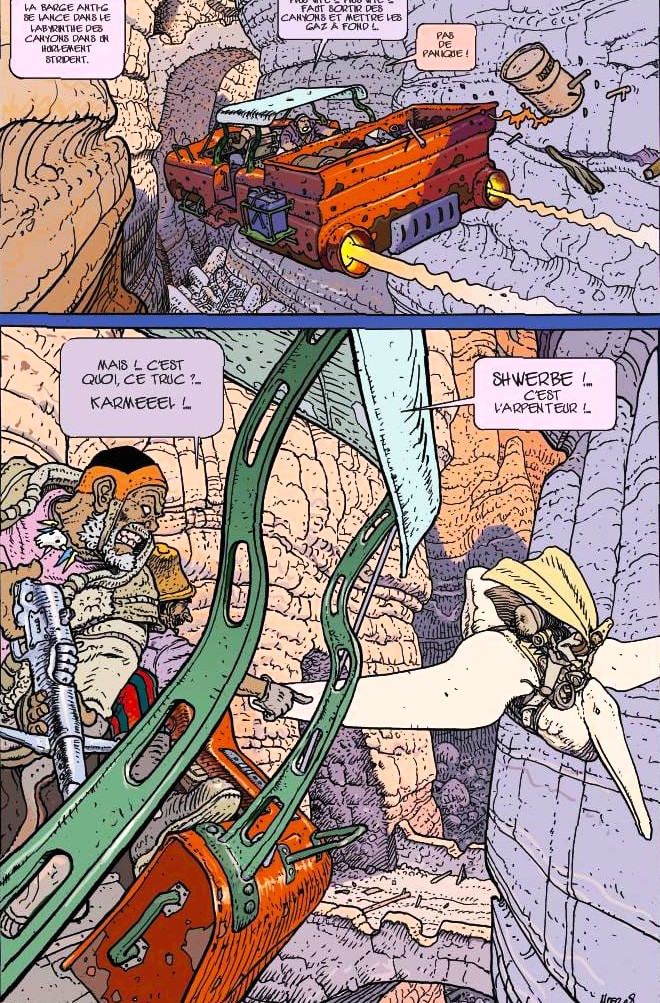

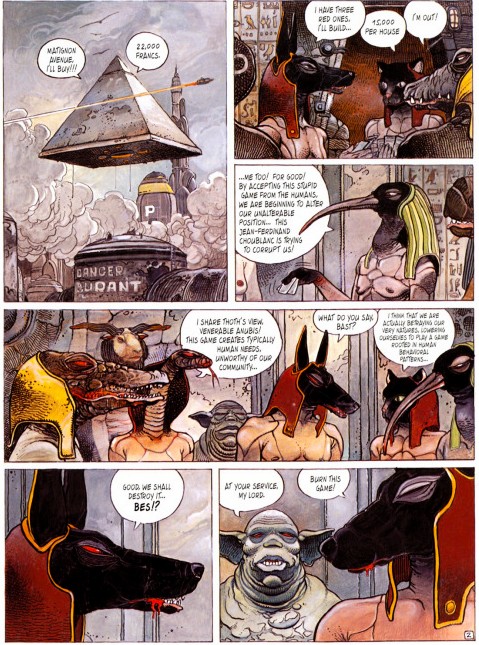

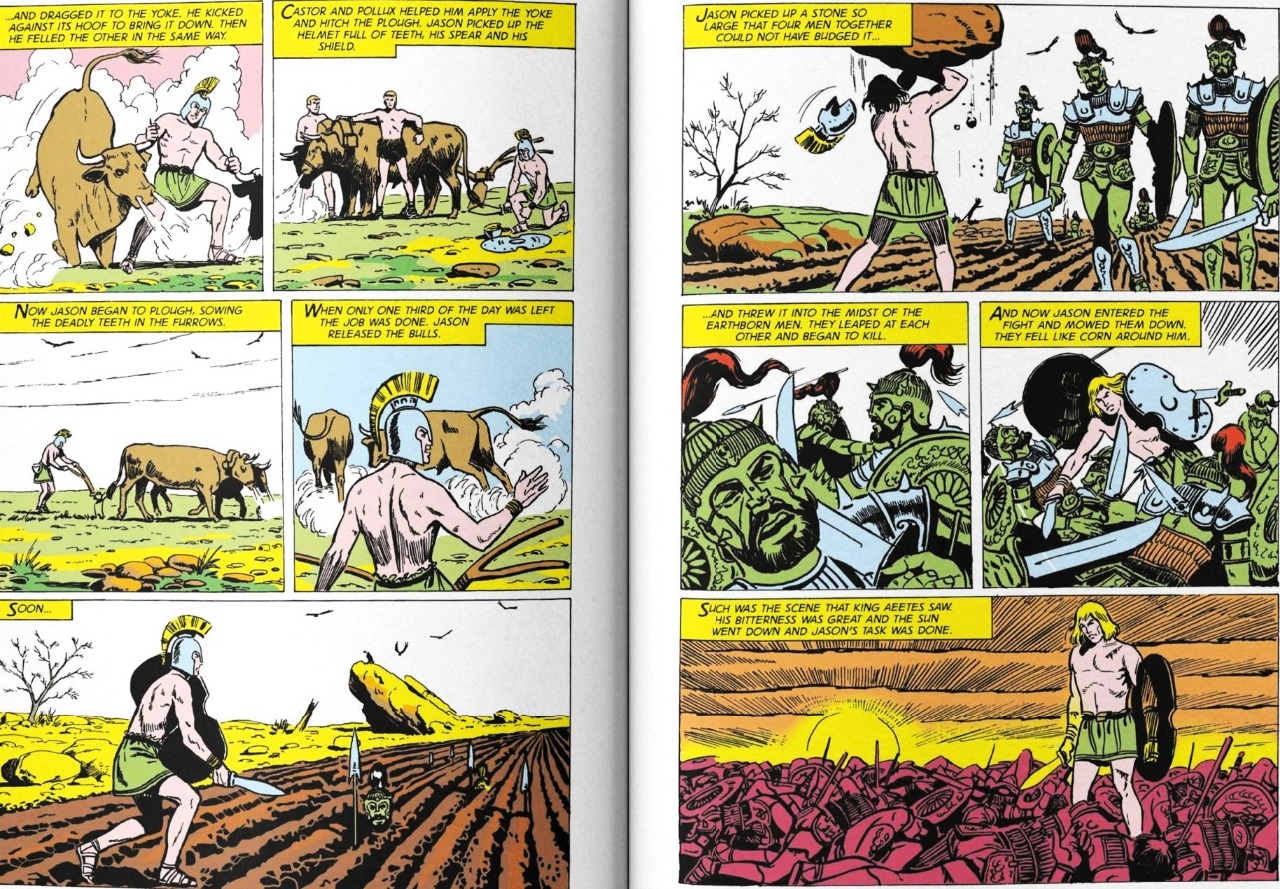

It is mainly ChatGPT that has come to dominate this general sphere of knowledge. It is a virtual assistant that through machine learning has accessed an incredible amount of information from books, websites, discussion foras, films, comics, dissertations, newspaper articles, manuals and all other conceivable material floating around out there in the web clouds. ChatGPT now devours all available information (and probably more than that) and shares it with data users all over the world.

For a few weeks now, it has hardly been possible to open either your computer or smartphone without being bothered by A.I. services that are being forced upon you. Talk about a tipping point! In no time at all, the world's computer users have more or less voluntarily been connected to an A.I.-created world that currently not only devours information, but also swallows enormous amounts of fresh water. Water that we need to live, have to drink and stay alive – eighty percent of our body weight consist of water. We cannot live longer than five days without drinking water and we need water to irrigate fields and crops. Freshwater makes up only three percent of the world's water and it is that water we need to be able to live, and two-thirds of it is still inaccessible in frozen glaciers, which are quickly thawing and disappearing into undrinkable seawater.

Huge data-based technology companies, such as Vidia, Microsoft, Google (Alphabet), Amazon and Meta, are now increasingly consuming our valuable and life-preserving freshwater to be able to cool and power their energy-guzzling data centres, where an estimated 9 liters of fresh water are needed for every kilowatt hour being used.

Computer engineering companies are more concentrated than other energy-intensive facilities, such as steel mills and coal mines. Buildings housing huge computers are constructed close to each other so they may share power grids and cooling systems, as well as transmit information efficiently, both among themselves and to their users. In Ireland, data centres account for more than 20 percent of the country's electricity consumption, most of them are located on the outskirts of Dublin. In at least five U.S. states, such centres' electricity consumption currently exceeds more than 10 percent of the states' total production.

Google processes up to 9 billion searches daily, and each such request via an A.I. server requires 7-9 watt-hours (Wh) of energy, i.e. a consumption of 63 to 81 litres of water. That's 23-30 times more than the energy required for a standard search. The large energy consumption also contributes to increased carbon dioxide emissions. However, it is possible that A.I. development is self-regulating and that energy consumption might be reduced over time. I have no idea, the only thing I know is that A.I. growth is continuing at a furious pace, something that I, and most people with me, have experienced firsthand.

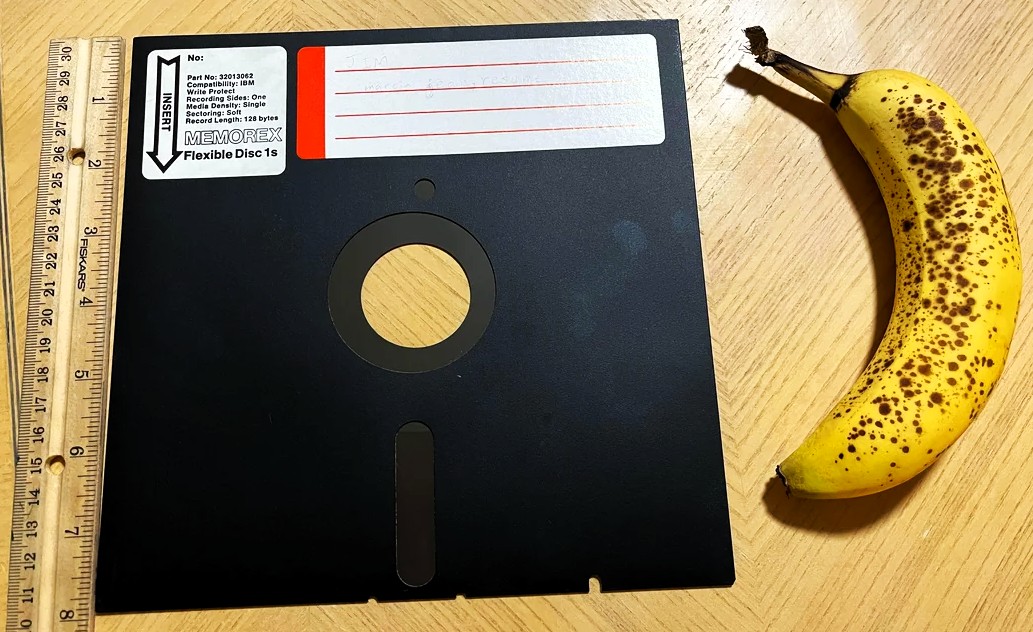

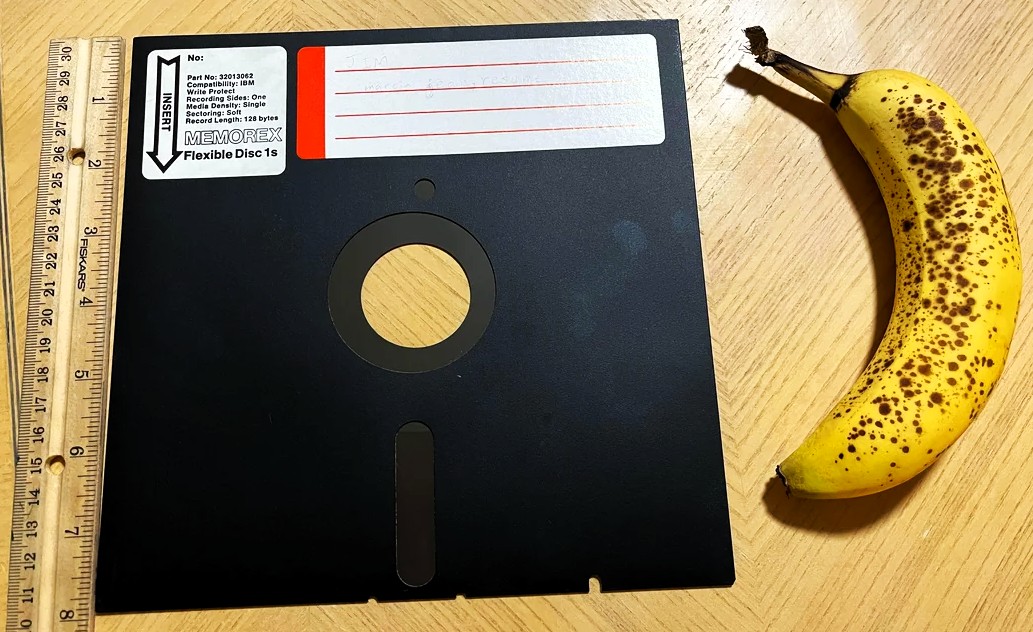

From the mid-seventies, I didn't have my own computer, but used university computers, which I first fed with punch cards, though these were soon replaced by so-called floppy disks, but I still had to learn certain codes to make it all work, and some days the entire network was shut down since the main computer had become too hot.

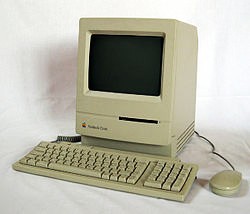

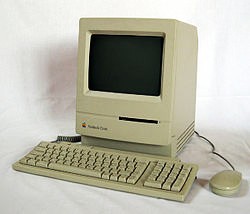

It was only later, when I with my research funding was able to buy a McIntosh that I was able to use the smaller, hard variants of floppy disks. I was very happy with my machine. I still have it and it still works, but of course I never use it. I also have my typewriters, one that I was given by my wife shortly after we met and an electric version that one of my brothers-in-law gave me.

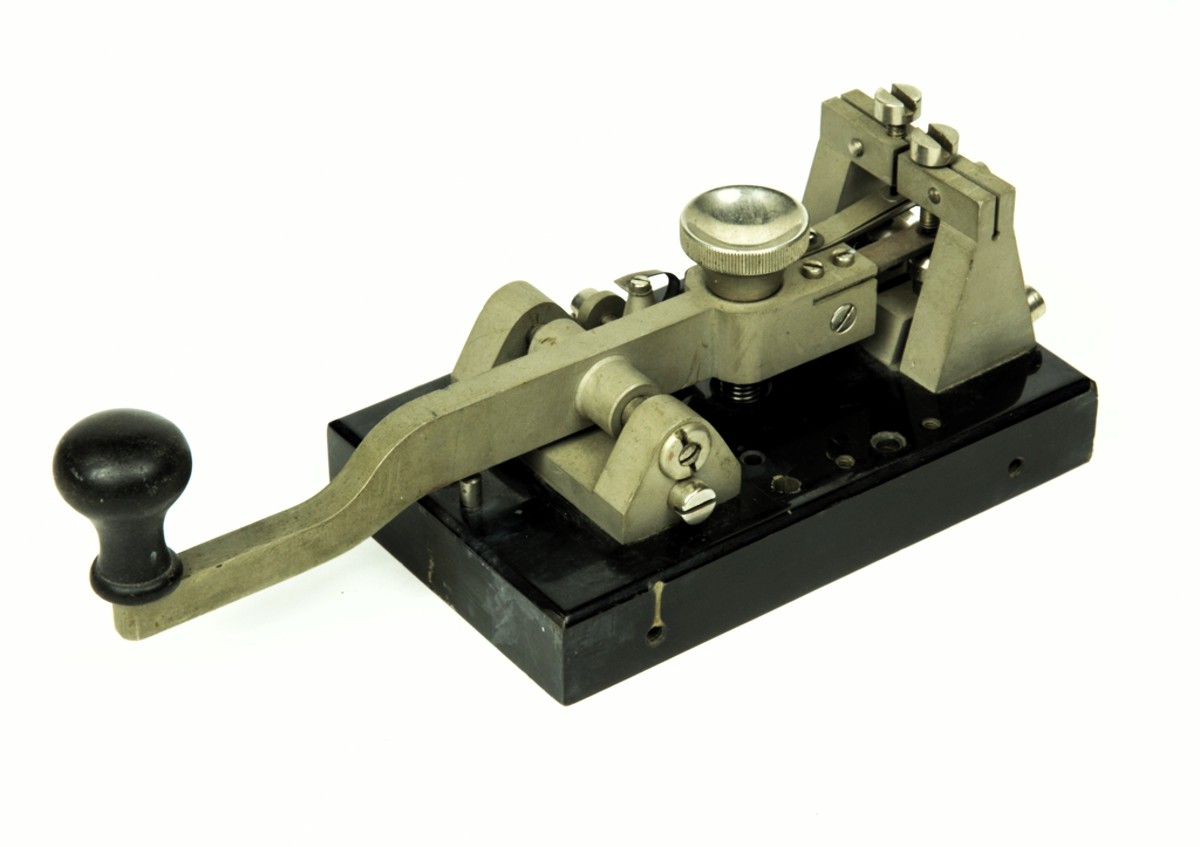

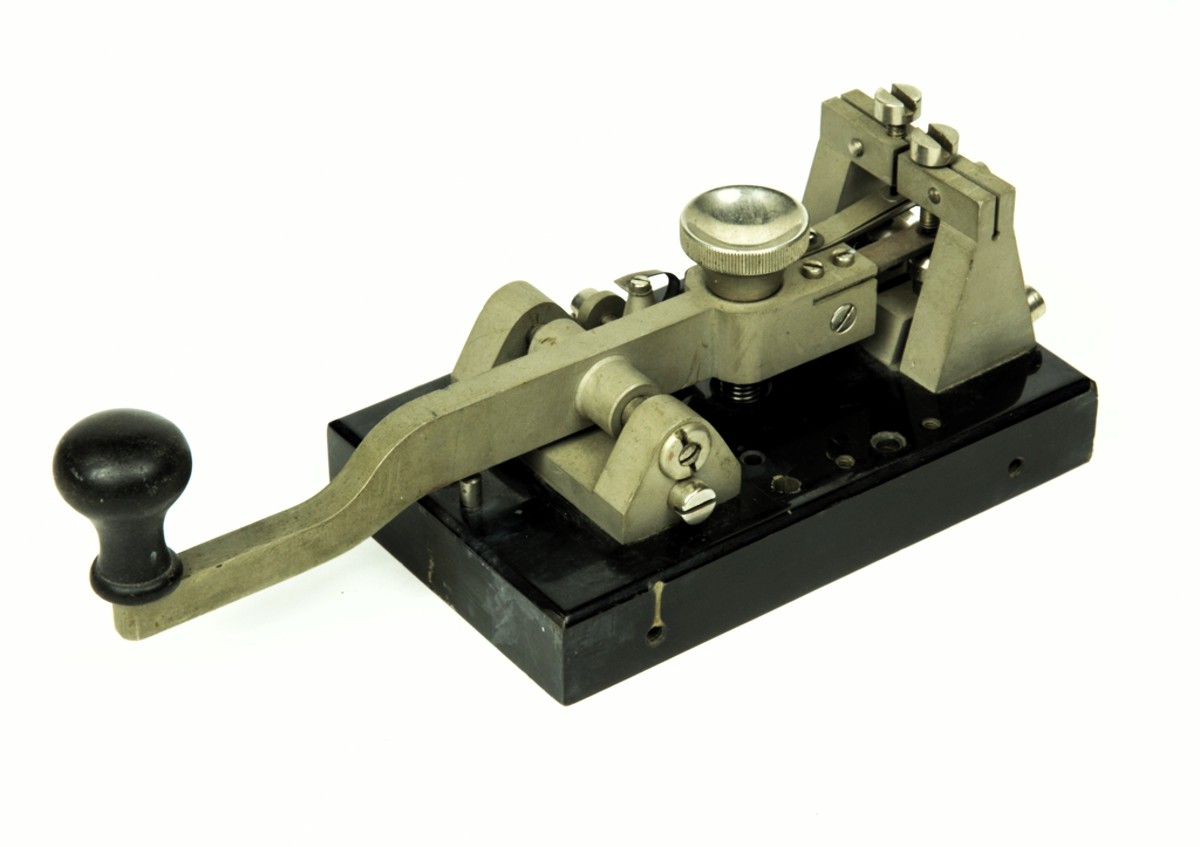

Something that I now appreciate was that I never wasted my youth on the extensive computer programming courses that various workplaces tried to make me participate in. My perception was that "soon you will be able to talk to your computer, so why do I need to waste valuable time on tasks that will be completely obsolete". Perhaps this opinion originated from me having done my military service as a radio telegraph operator and after my first month of rehearsal service found that the Morse telegraphy I had learned was as relevant for modern warfare as cavalry shocks.

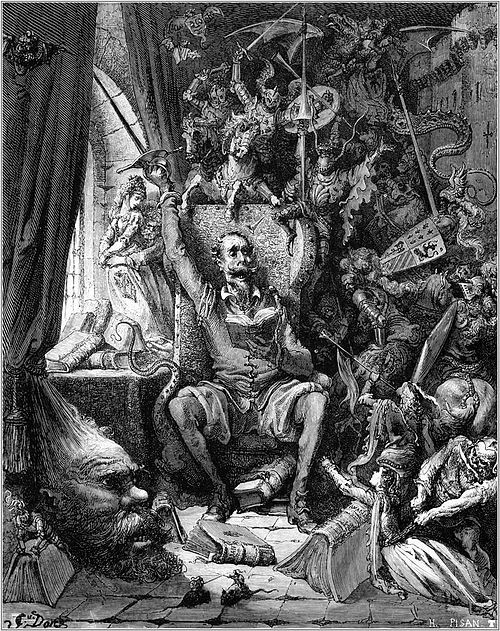

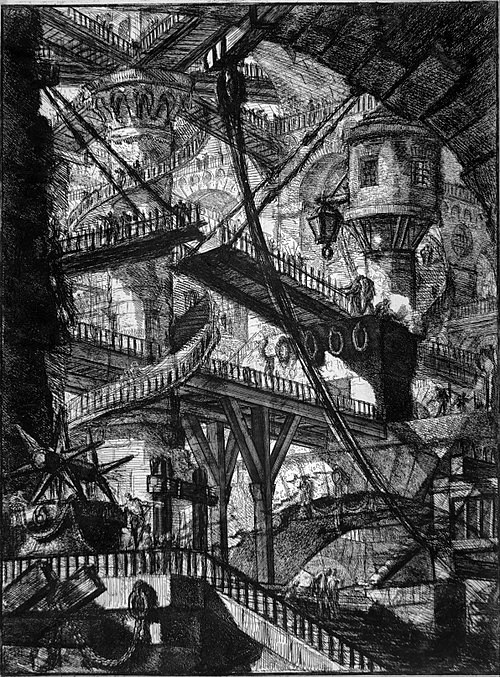

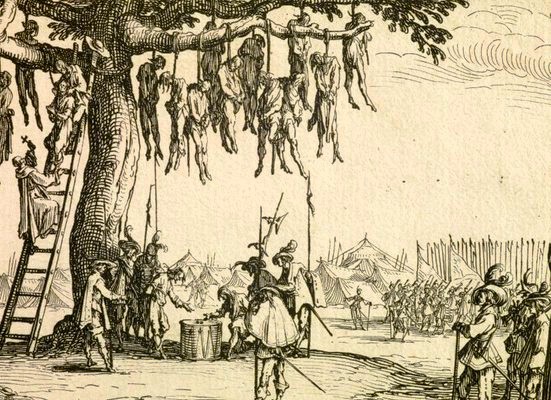

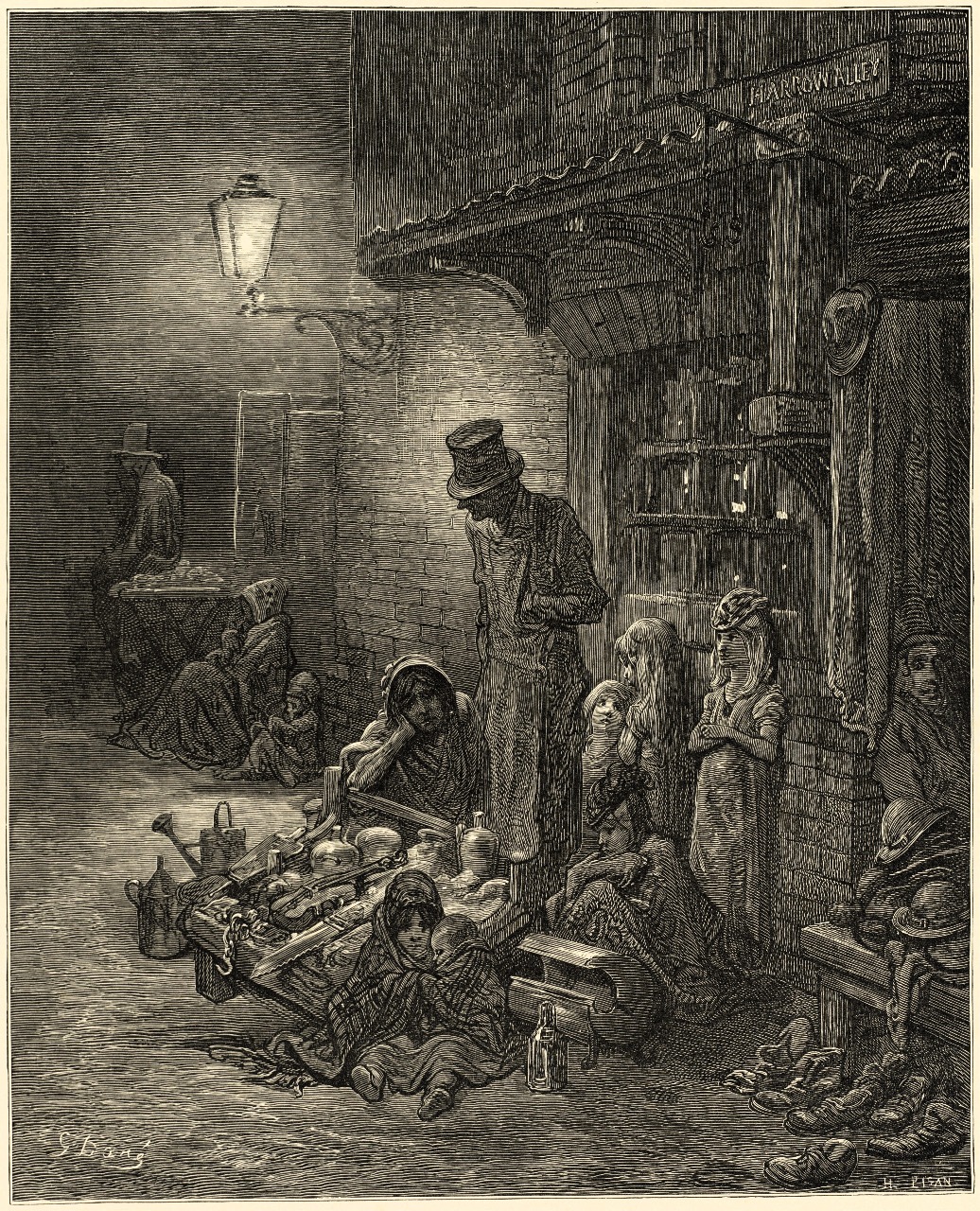

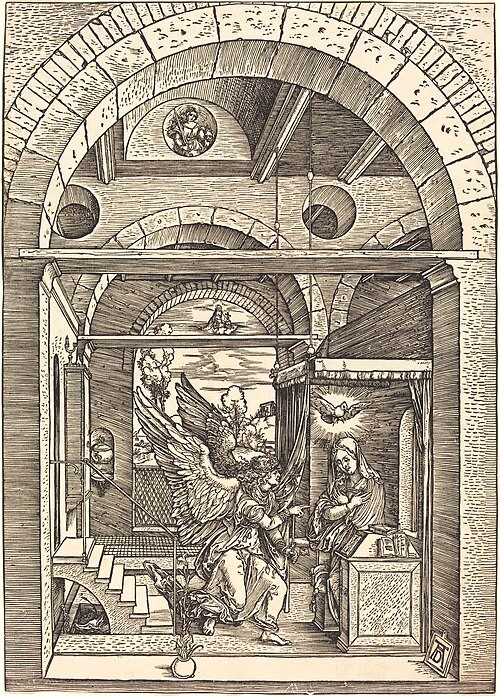

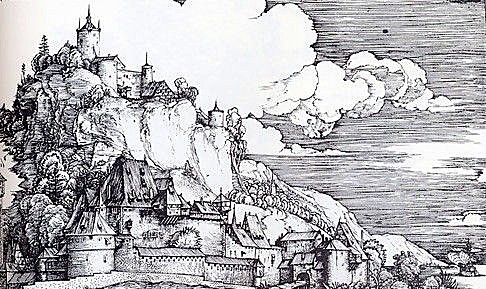

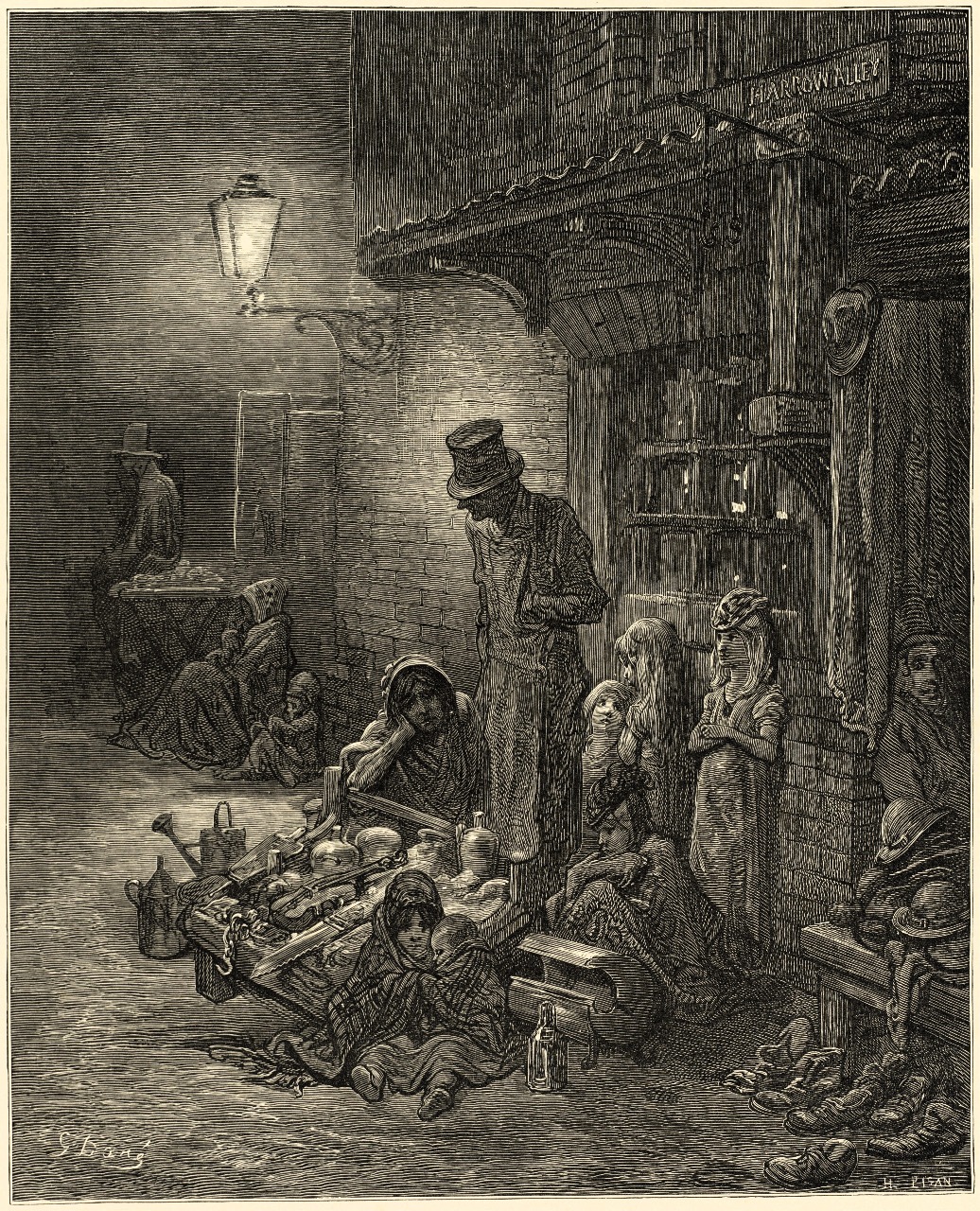

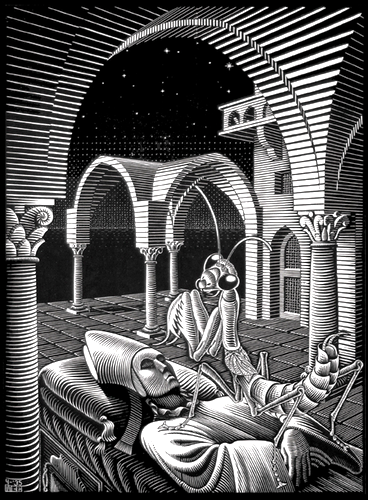

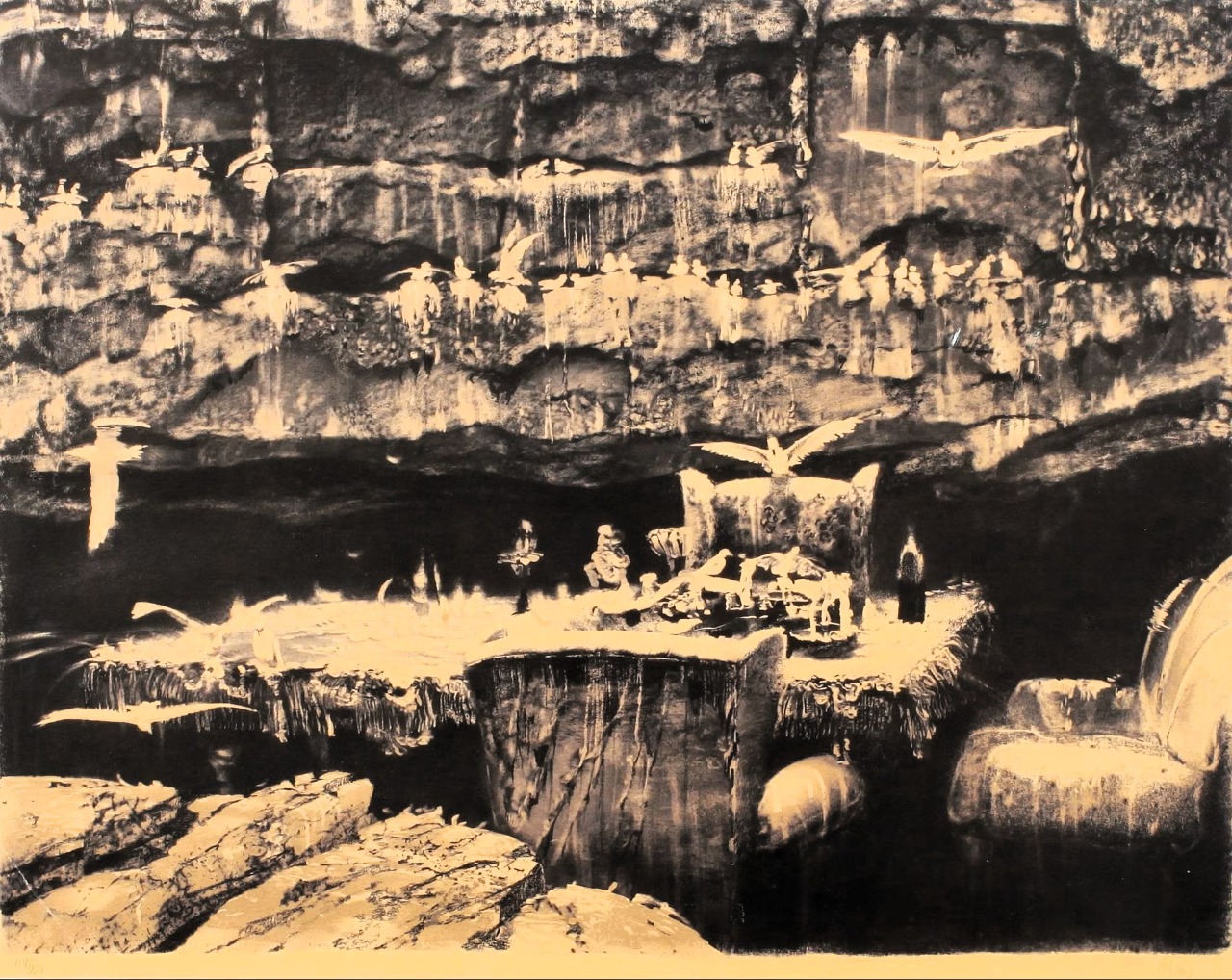

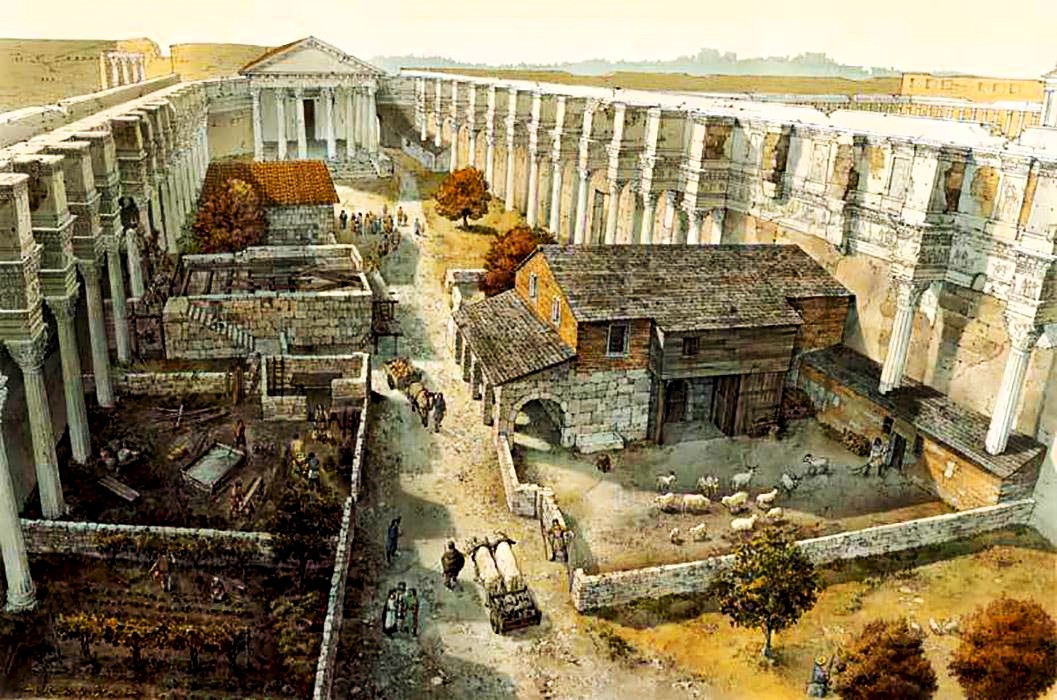

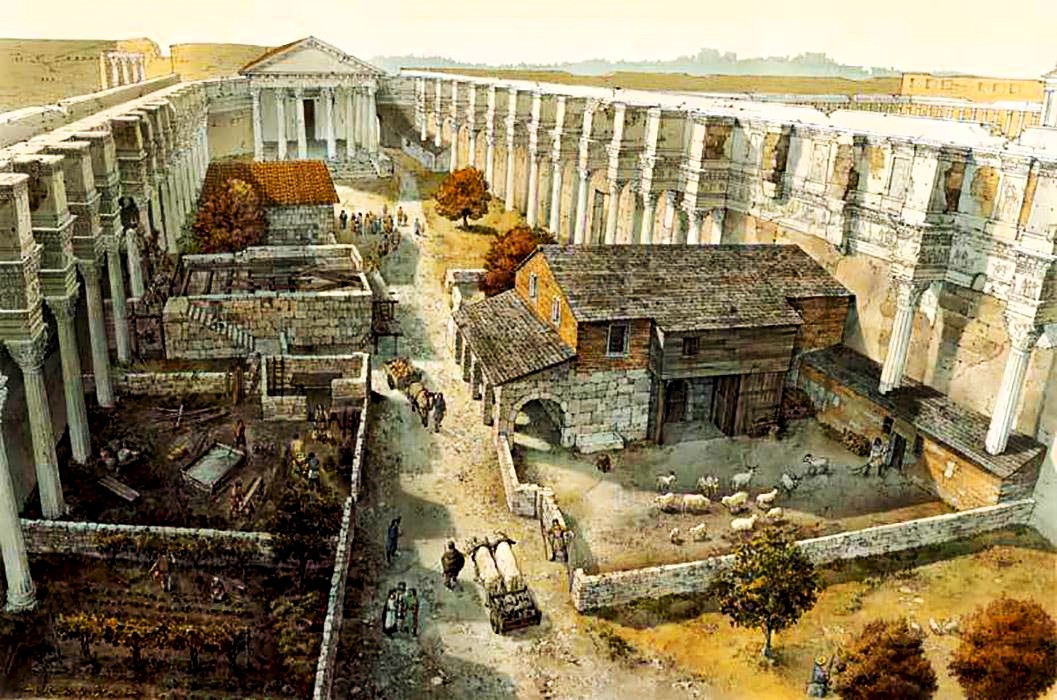

My generation has thus been thrown headlong into a maelstrom of unimagined development that many of us have had difficulty adapting to. I sometimes feel as if I am still living in the Middle Ages. Like an old monk I read books and write as often by hand as I type on my computer. Outside my room, life roars on and of course I am also reached by some of its gusts. For many, for my own part I'm not quite sure, the steadily increasing speed of this swirling hurricane of breakneck commercially dominated artificial intelligence development is very worrying.

In a short time, the most astonishing results of this "progress" have hit us. Especially if we live within the richer and more privileged sphere of our world. For example, I remember very well how we in 1994 were offered the services of Amazon, in 1997 came Google, and in 2001 Wikipedia (which I actually appreciate), in 2004 followed by Facebook, then came a host of social networking services – Twitter Instagram, Tik Tok,4Chan, Linkedin, Pintrest, X, Reddit, and I do not know how many more, probably several thousands of them. The founders of these and similar web phenomena have for their own benefit amassed power and fortunes far beyond human understanding.

I remember how in the mid-1990s, after a few years of absence on southern latitudes, I took up a job at my old high school and found that all my colleagues, at least most of them, were walking around with small cordless phones. I had not seen such gadgets before and a few years later I received from a friend his old, used one. New, more efficient models had come out and then, as now, it was important to be technically updated and before your old electronic equipment had become hopelessly obsolete it was necessary to acquire the latest, fresh and more sophisticated artefact

Most of us probably have somewhere a box of used, by now quite useless mobile phones. Especially after smartphones had been introduced in the early 2000s. Nowadays most of these gadgets have personal digital assistants, palm-sized computers, portable media players, compact cameras, camcorders, game consoles, e-readers, pocket calculators, GPS, and much more.

For a few years now, life has become quite complicated if you don't have a smartphone with an installed bank code and the ability to read QR codes. If you lack such sevices, you are ignored by the authorities, cannot park your car, or eat at a restaurant. The QR codes have gradually become an ID card, a key that opens and closes gates and furthermore they are yet another computer-based method that allows Big Brother to follow you wherever you are and influence your life.

When I began working in Stockholm after a few more years in distant countries, I found that well-dressed yuppies walked around the streets and talked to themselves, something I had previously only seen been done mentally disturbed homeless people in New York. However, I soon discovered that it was their smartphones the smartly dressed professionals were conversing with, using discreet earbuds.

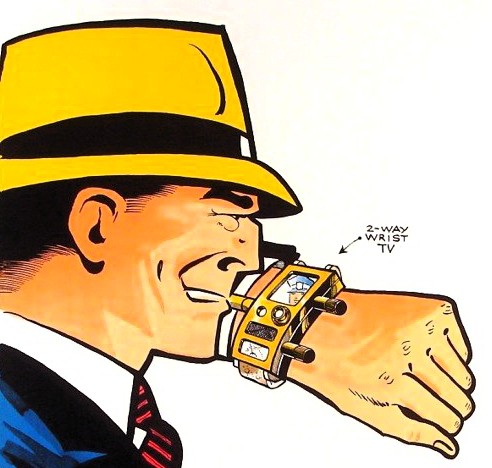

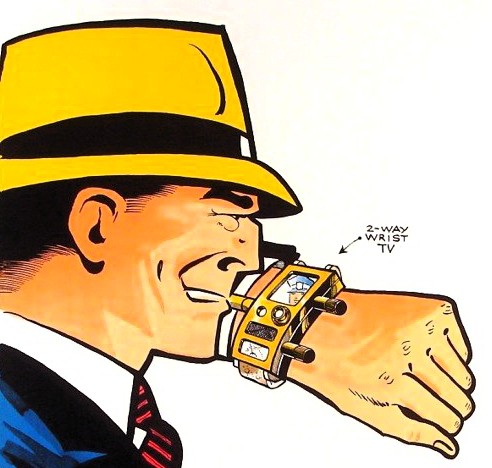

During my childhood, I often read the daily Expressen's comic strip supplement where, among others, the adventures of Dick Tracy could be followed. I was amazed by the detective's TV wrist phone, which since the mid-1960s made it possible for him to communicate with his colleagues through live imagery. At that time, I could not have imagined that smartphones would soon become a reality.

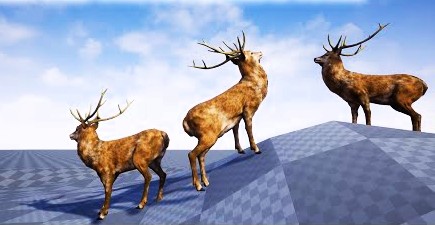

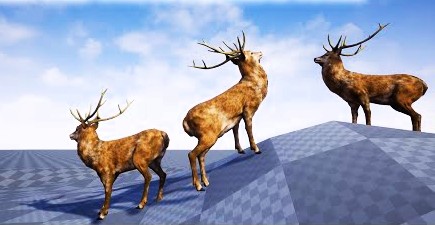

I was even more astonished in 1996 when, during a formal dinner, my wife and I ended up next to a researcher who told us that he had turned his computer into a virtual aquarium in which he had created a pike and its habitat. He had then, through various simulations, manipulated his pike's surroundings and existence – adding or removing oxygen, changing the water temperature, as well as its acidity, experimenting with some environmentally hazardous toxins, increasing and decreasing the light and performing a variety of virtual experiments. On several occasions he had both killed and resuscitated the pike.

We found it all interesting and rather strange. No wonder we wondered what the researcher's "computer aquarium" looked like, this was long before A.I.'s ability to simulate imagery production had become as sophisticated as it is now. The researcher was a great enthusiast and after talking about his pike during dinner, he did by the dessert describe his research on herd animal behaviour. In another computer he had created a virtual reindeer herd. His wife interjected that "last week one of his reindeer disappeared and he has no idea where it went."

It all sounded too unbelievable to be true, but it sure was. I have later found that Lund University has several professorships linked to biomimetics, where you use computer technology to simulate habitats, various systems and elements within nature, in order to investigate and solve complex problems. It can be molecular biomimetics that study biological reactions at the molecular level to be able to use the same biological principles while developing methods for sustainable production of solar fuels and chemicals. Or to study nature's underlying mathematical patterns and with their help influence design and technological development.

Biomimetics might be used to understand and reproduce both beneficial properties and harmful changes occuring in nature, both through direct observation and at the microscopic level, and thus find new ways to prevent and treat diseases. And of course, as our table neighbor, investigate how different habitats and their inhabitants are affected by, adapt to, or counteract changes in their immediate environment. The field of research is broad and constantly evolving.

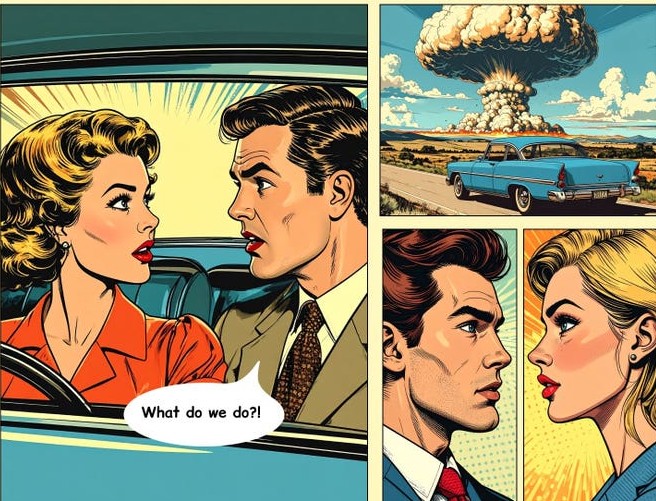

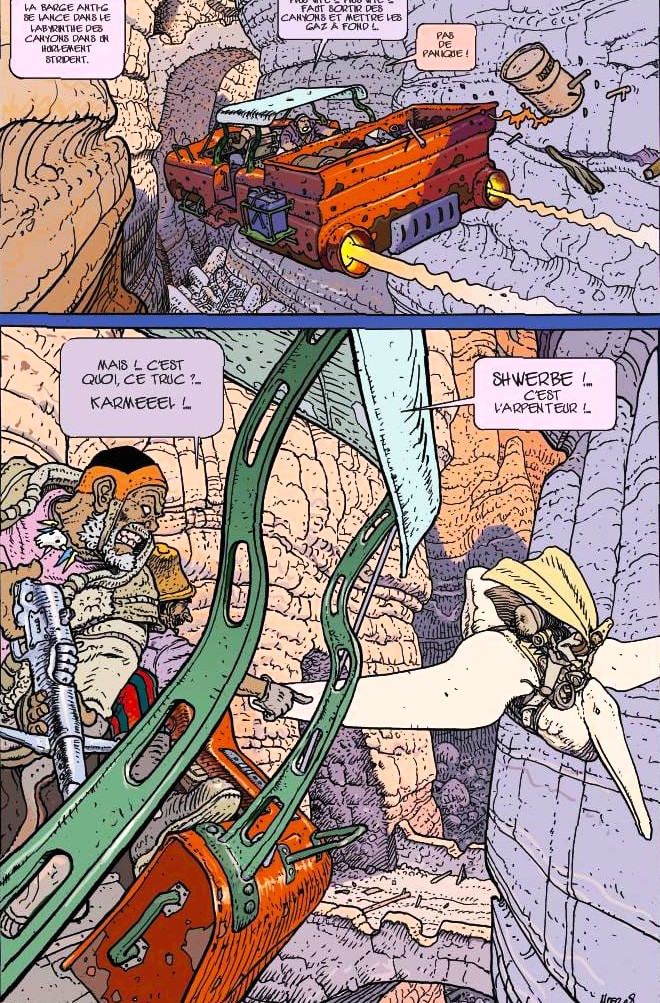

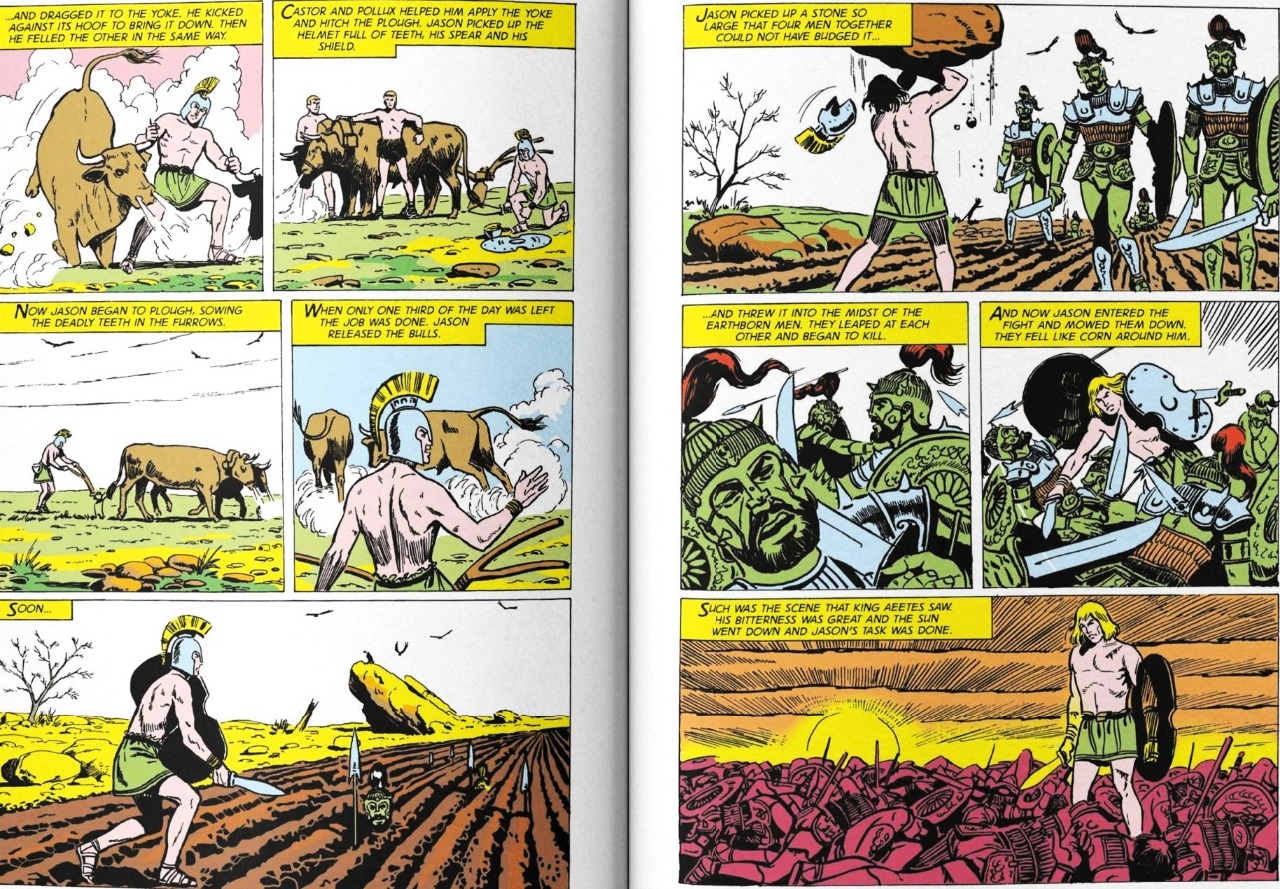

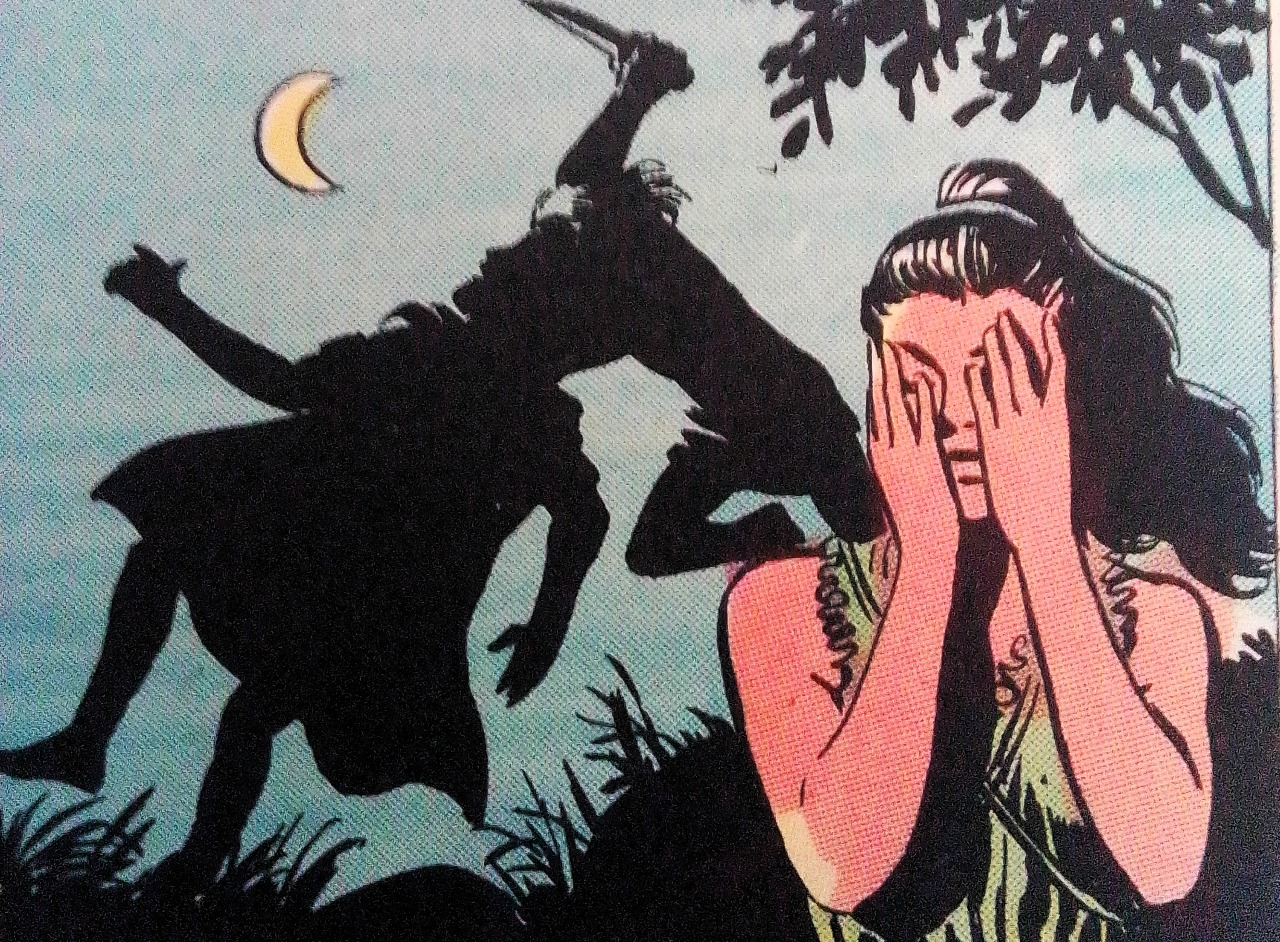

Speaking of aquariums, my friend Krister, a humanist who is remarkably well informed about most things, not least A.I. development, told me a couple of years ago how he had tested A.I.'s ability to write stories and draw comics. He asked the A.I. to tell and illustrate in comic form an aquarium fish's version of a family’s constant quarrels that he had watched through the aquarium glass. Something that had already been tried by, for example, the Disney Company in Finding Nemo and the Monty Python gang in The Meaning of Life. Krister gave a few clues to A.I., which in a short time had been able to produce a well-drawn and quite good story. I now find that the internet offers a wealth of opportunities to learn how to create comics with the help of A.I.

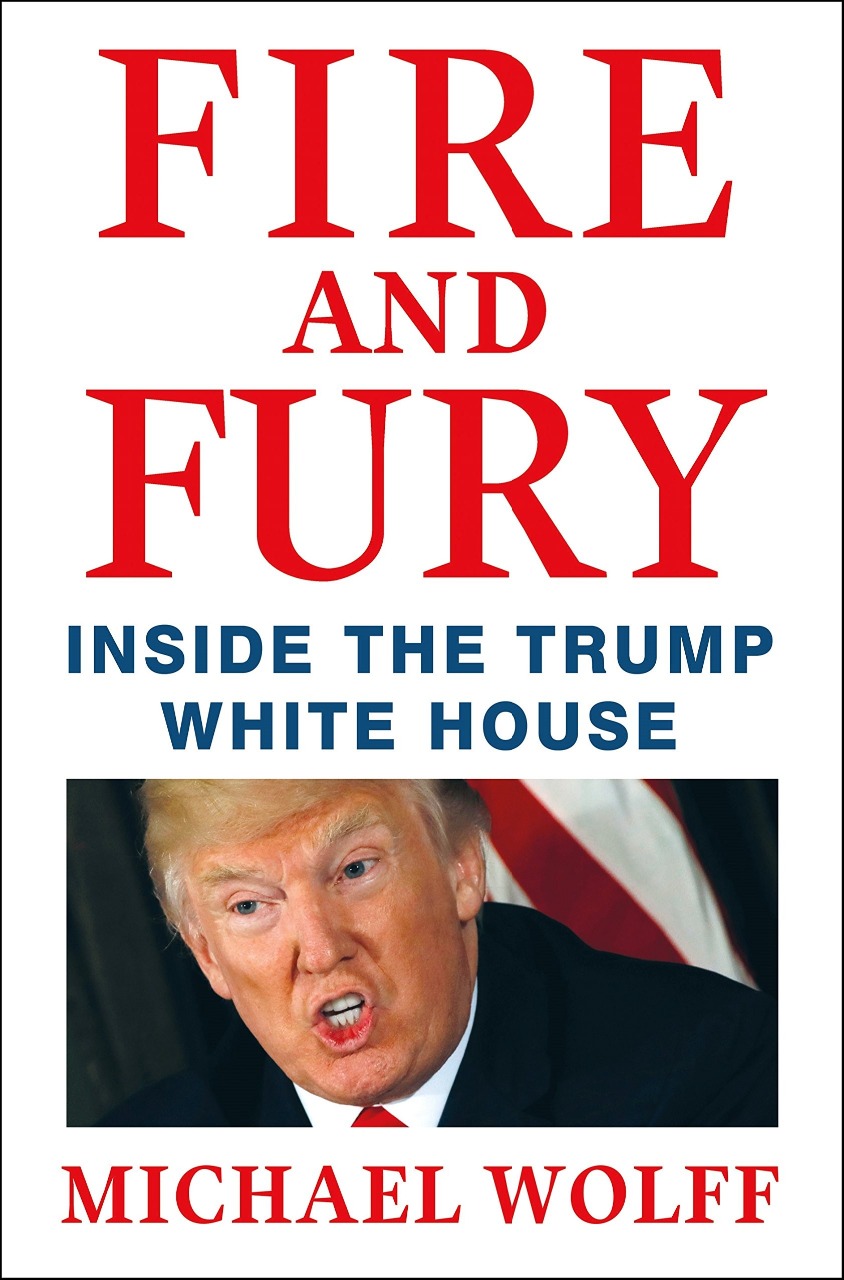

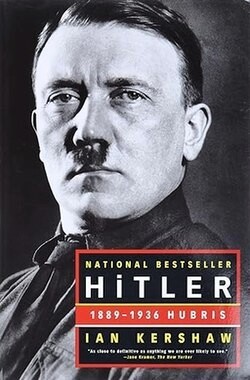

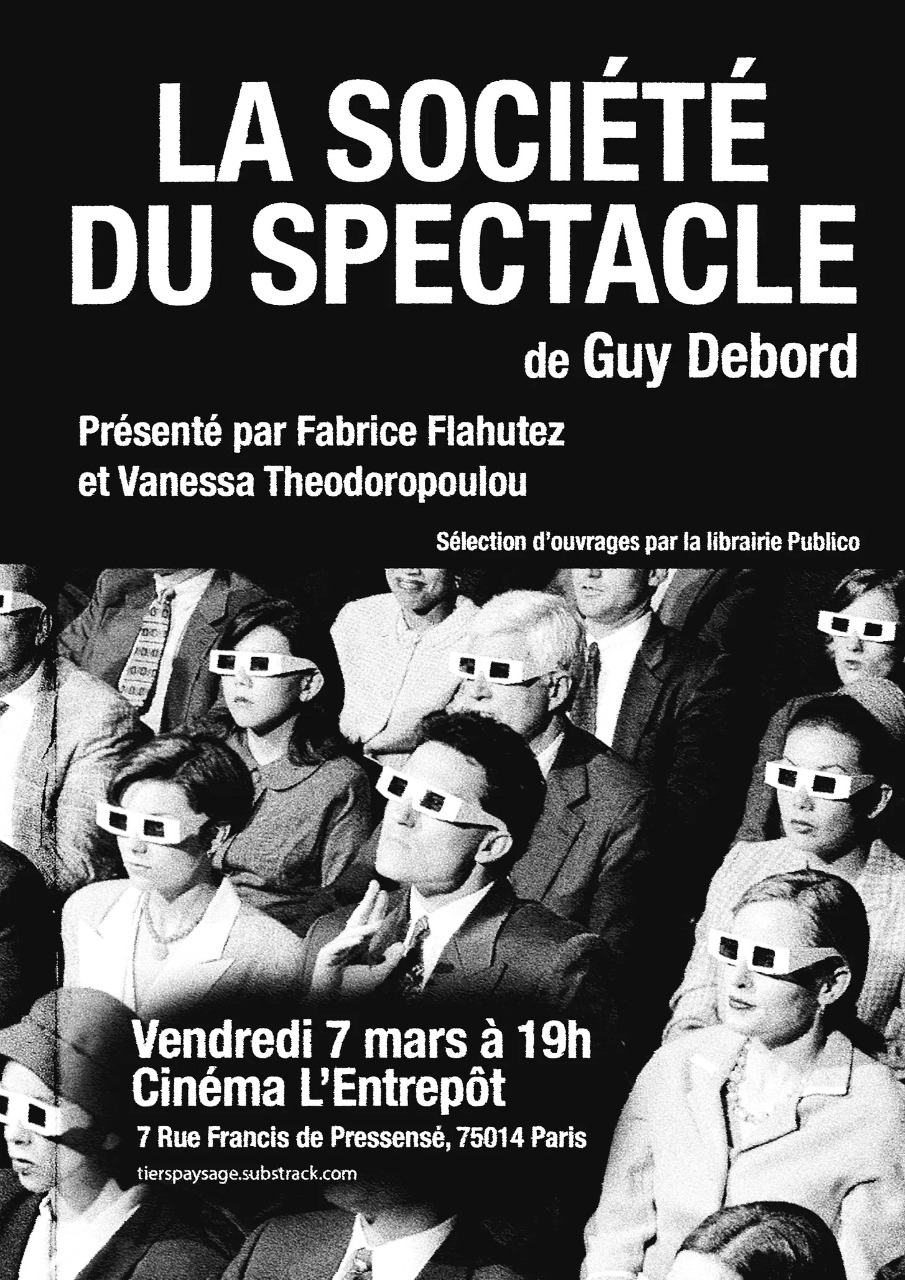

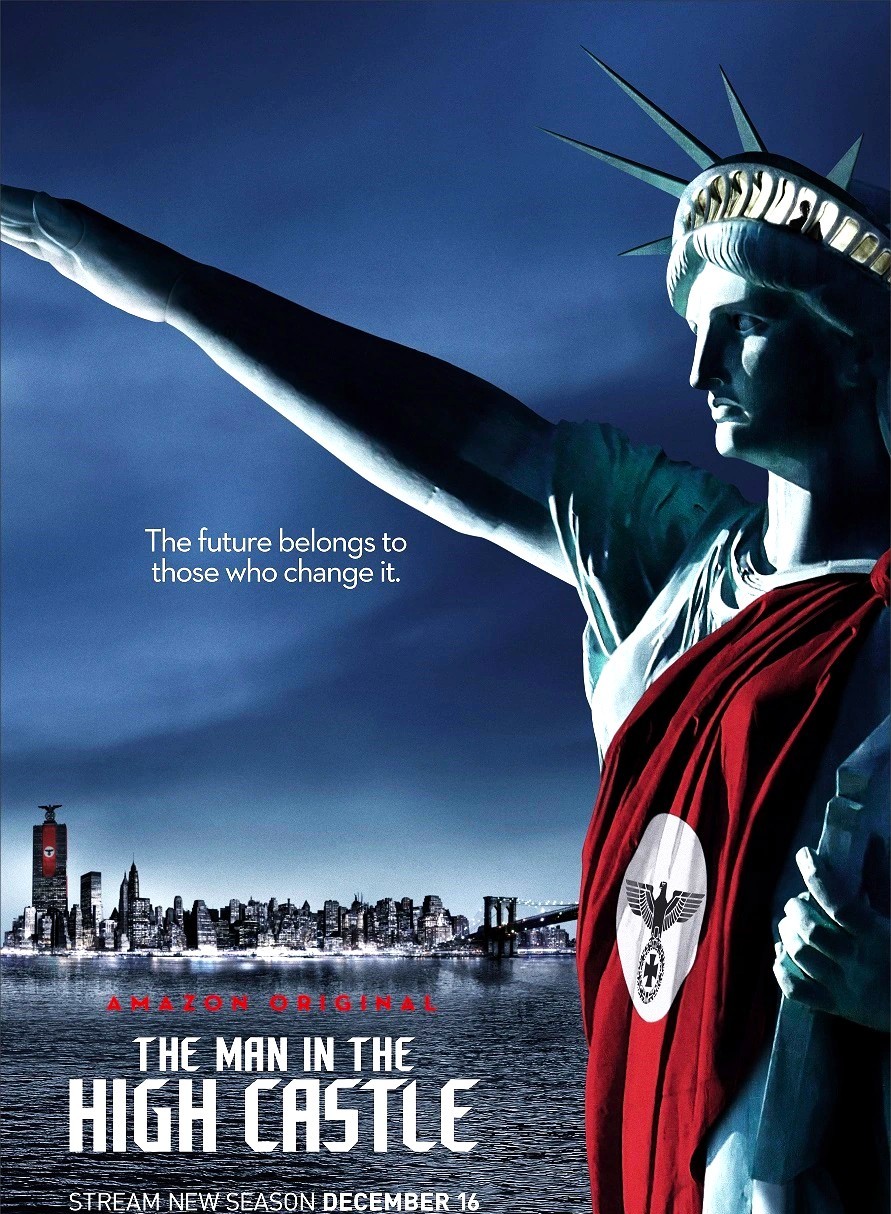

With the help of A.I., anyone can now, even in the absence of drawing talent and writing ability, produce really good images and literary texts. Often, influencers on both the left and right aisles of the political spectrum use A.I. to spread their opinions. At best, it is done with a "humorous" touch that reveals what it is all about. A.I. tricks, such as the distressing videos and pictures that the deplorable President Trump occasionally publish on his site Truth Social. For example, a distasteful video from July 21 last year presenting a fake arrest of a humiliated Obama, presumably part of Trump's desperate attempt to divert attention away from his presence in the so far largely secret Epstein files.

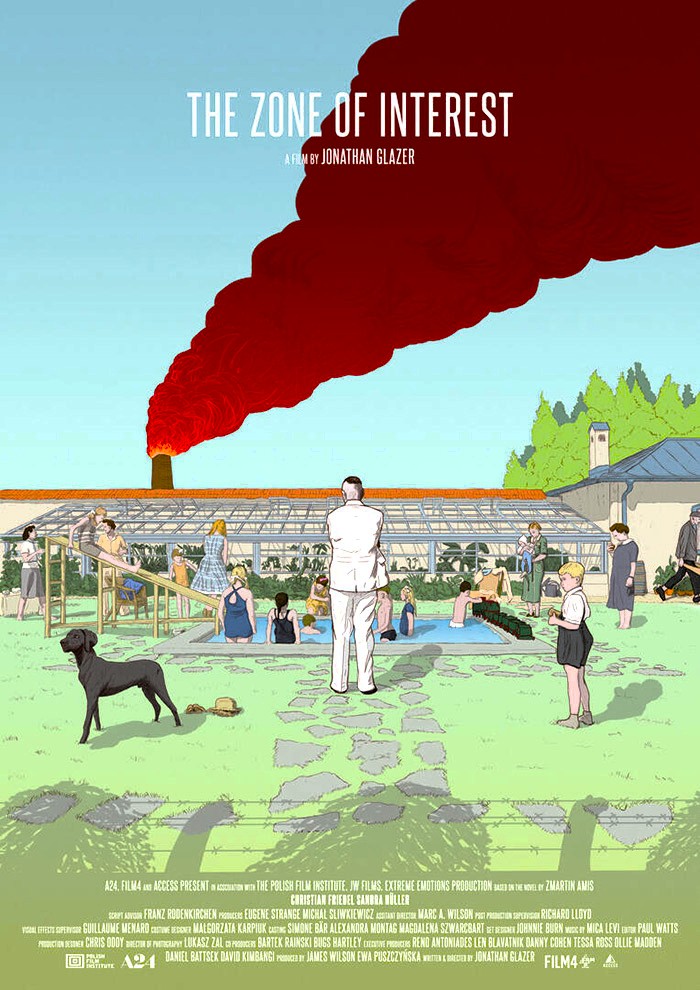

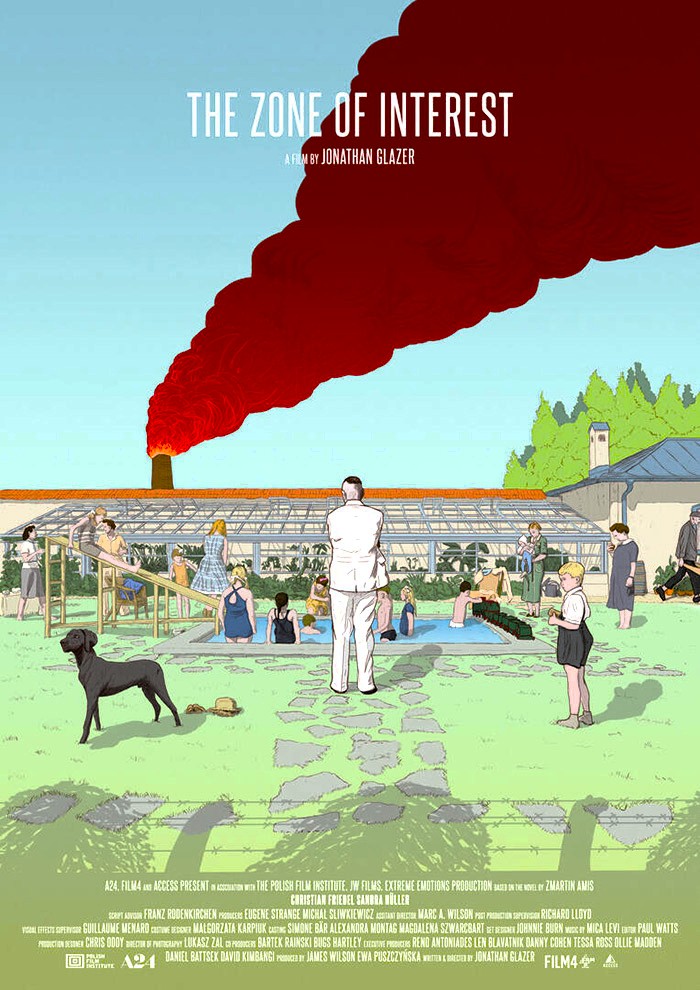

Not to mention the disgusting video of how a bombed-out, starving Gaza has been transformed into a depressing resort. Where is the humour hidden within such a terrible emotional chill? Like a Nazi making fun of concentration camps and mass extermination.

It has been established that more than fifty percent of the websites on the Internet are now A.I.-produced. A few days ago, I heard that my nine-year-old granddaughter came home from school and, enthusiastically encouraged by her schoolmates, wanted to see a video with Ballerina Cappucina. Since I had never heard of her, I looked her up online and to my horror found an A.I.-generated ballerina with a cream-topped cup of cappuccino for a head. A kind of stupid mix of Hello Kitty and Barbie used for sexual innuendos and the A.I. generated lnallet dancer was often beaten to pieces by one of her “boyfriends”, like Cappucino Assassino, a ninja coffee cup with two eyes and two samurai katana swords he used to cut up his victims at night.

These characters are part of a meme phenomenon called Italian Brainrot, created by Fabian Mosele, an Italian animator living in Germany, who in early March 2024 created an A.I.-generated shark wearing Nike tennis shoes while dancing to an idiotic electronic thumping tune called Trallero Trallerá. According to its creator, Italian Brainrot is just one of many contributions to a trend of “dank memes”, which absurdity lies in the fact that they are not really funny at all, but “just weird”.

From Trallero Trallerá, a multitude of A.I.-generated characters quickly developed and these are now flooding the Internet, exciting kids, young people and commercial stakeholders to create their own Italian Brainrot mimes, as well as produce and buy an explosive amount of merchandise – dolls, fast food, trading cards, and so far, primitive video games, etc.

All Brainrot characters are hybrid creatures made up of animal parts and objects such as plants, food and weapons, which meme videos are often commented on by a male narrator, also A.I.-generated. Absurd violence and profanity (exemplified by Shrimp Jesus) are a significant part of these Generation Z creations.

With each passing day, we are more and more helplessly imprisoned within a cage being constructed by technocracy. It's been years since we were able to move around freely, without constantly worrying about being unreachable. Now my loved ones are worried and annoyed that I don't hear the ringtones from my smartphone, or don't immediately respond to their attempts to call me up. They want to be assured that they have the opportunity to be in constant contact with me. I understand them, I have become the same myself. I also get worried when I notice that I have forgotten my mobile at home and thus become "incomunicado".

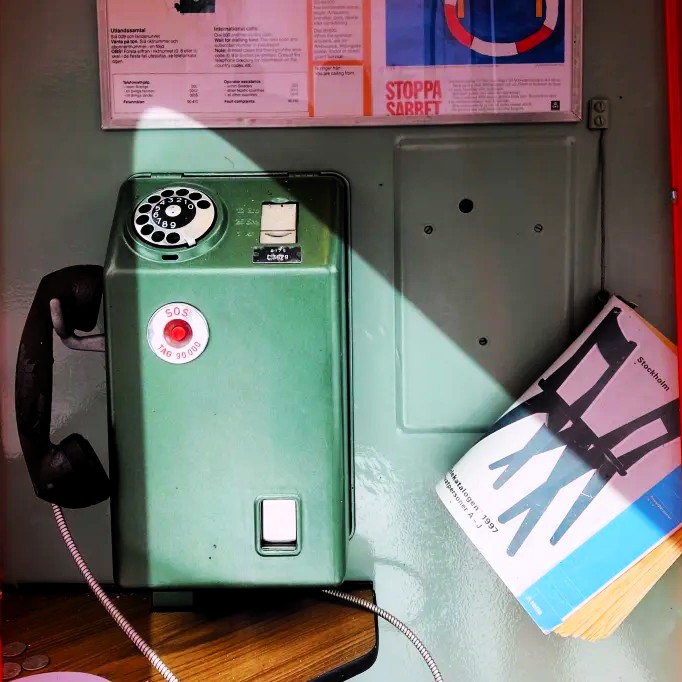

I have a hard time remembering the time when I didn't constantly carry my phone with me. In those mobile less times, as soon as I was out in town and felt that I had to contact someone, I frantically searched for payphones and made sure to always carried with me small change.

At that time, if I was in unknown places, or on my way to various meetings, I was referred to maps. Fifteen years ago, during training for relief efforts in foreign countries, I received detailed instructions on how to use the then complicated GPS system, now it is conveniently installed in my smartphone and can even graphically show how I move through unknown areas.

In the past, I was constantly sending letters and cards to my friends. I remember how I worked as a postman in my youth and the hectic times and welcome income that Christmas card sorting entailed. Now there are no mail boxes anymore and post offices are closing down, as are bookstores and video stores. We live in and with our computers, mostly in the form of smartphones.

It was with concern and some shock that I, sometime in the mid-2010s during my last time as high school teacher, discovered how enslaved so many students had become under their smartphones. The attention span of several of them had shrunk to a minimum. Ignoring their surroundings, they were immersed in their smartphone world. The boys' entire attention could be captured by a virtual motorcycle speeding through a mountain landscape, or a bullet rolling within a maze, while the girls devoted themselves to taking selfies whenever the opportunity arose, or letting themselves be absorbed by the distressingly superficial "reality show" Keeping up with the Kardashians.

As soon as they were going to work on their own, the mobiles appeared, while my pupils tried to make me believe they were using them to solve their tasks, which also was bad enough. Or they simply ignored my presence and that of their comrades and let themselves be drowned in a bland mobile existence.

If I asked someone who had become absorbed by her smartphone what she was actually doing, she might answer that she was involved in an emergency call with her mother. Something that made me wonder if her mother's name was possibly Kris Jenner. This could come as a total surprise to those Kardashian fans and perhaps make them temporarily wake up from their zombie-like mobile slumber. How could an old codger like me know who Kris Jenner was? And... Kim, Kourtney, Kholé, Kendall, Kylie, Robert, Caitlyn or anything that the members of that annoying Kardashian bunch were called. As a teacher, you are sometimes forced to learn all kinds of rubbish in order to understand your pupils’ often weird and crude world, which by the way does not originate from them, but is served up by callous commercial interests.

In vain, I pleaded with my colleagues, most of whom were significantly younger than I and thus also domesticated into the illusory world of cybernetics, to join me in pleading to the school management to ban the use of smartphones during lessons. To my surprise, several of them disliked my opinion and believed that the use of smartphones could actually contribute to teaching and that I had not yet learned their great possibilities.

I wondered. Especially since I found that several of the students could not read a text that was more extensive than one or two paragraphs. They could not concentrate for more than five minutes. Some had difficulties in writing by hand, let alone watching a movie and following the action, after a few minutes of blackout the mobiles were out.

However, I have to admit that there were exceptions and the students who really made an effort, demonstretde interest and a willingness to learn, were often better than most students I had previously dealt with – a small special elite, polite and attentive, regardless of what social group they came from.

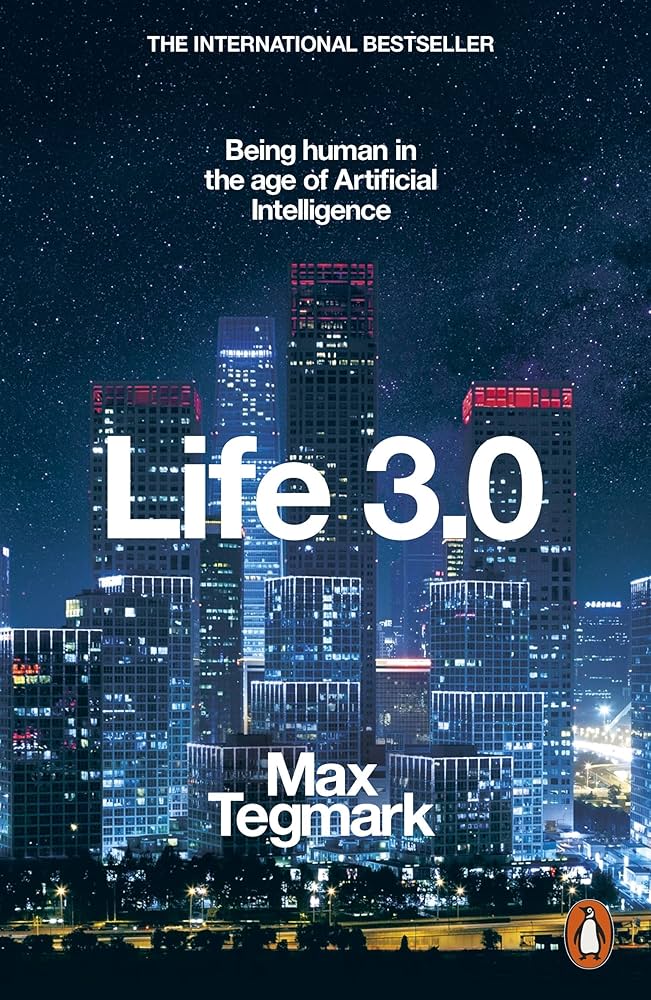

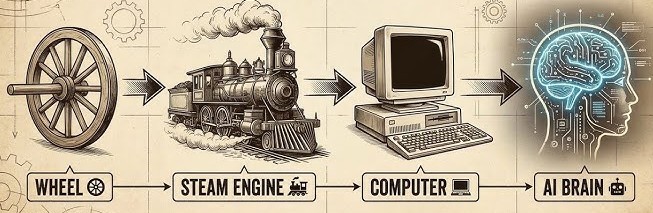

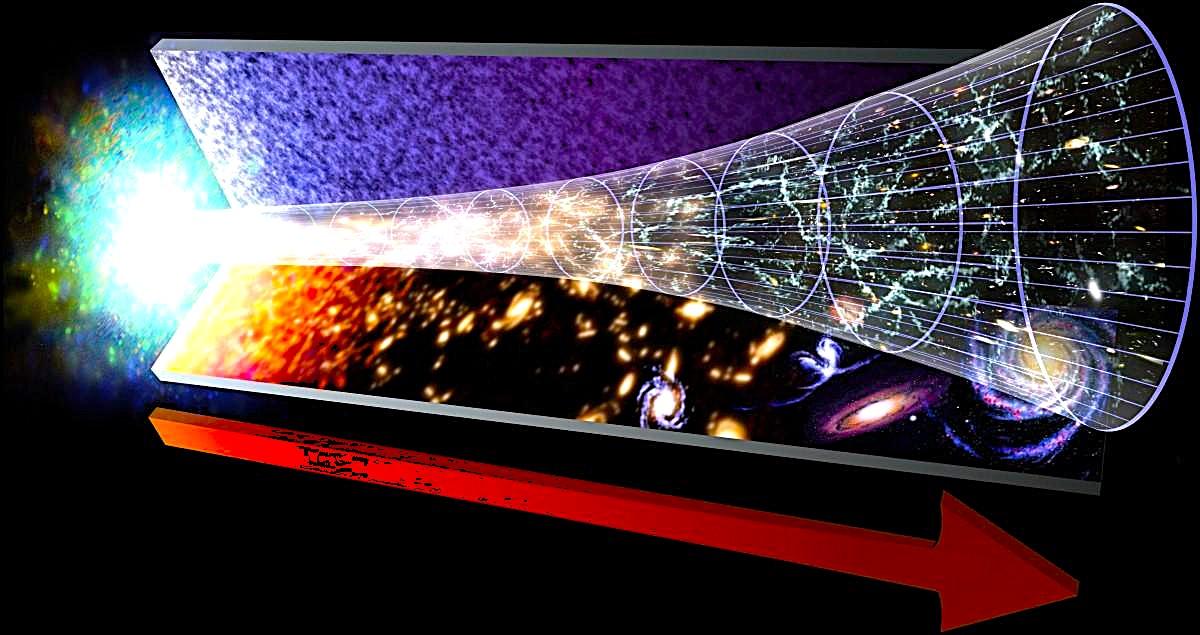

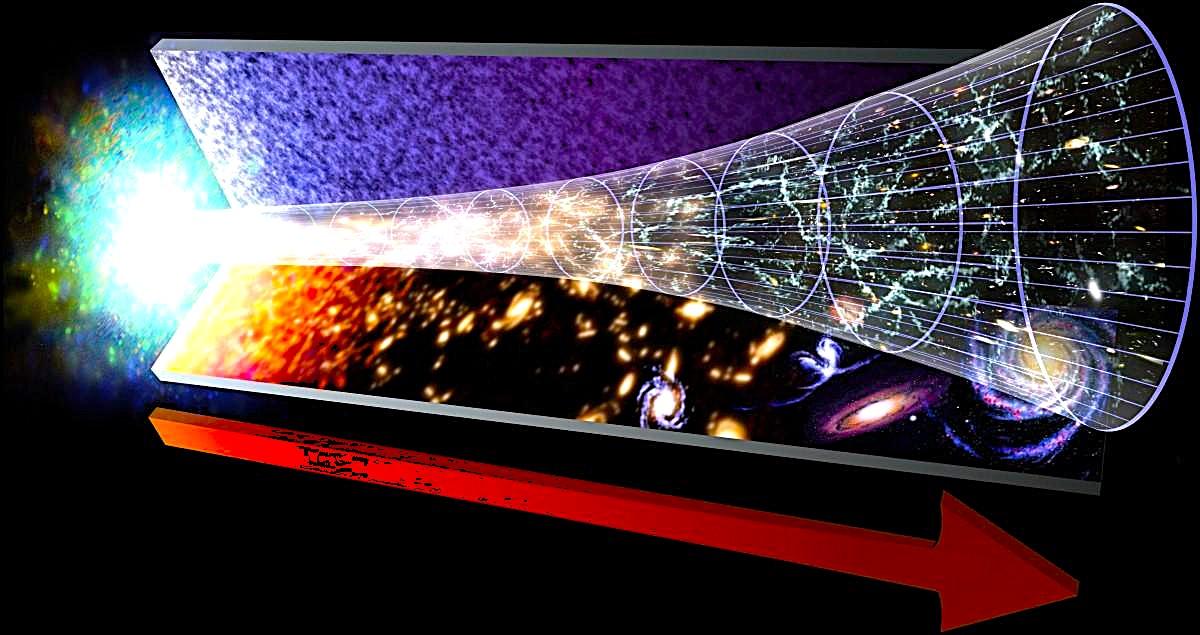

All of the above are certainly trifles that I share with other colleagues and comrades of my generation at our latitudes. Trivialities if you compare them to what is now appearing along the horizon – a veritable A.I. explosion that in a short time will turn much of our past into a strange story that may seem far more distant than really is. To better understand what A.I. is really all about, I recently read Max Tegmark' s Life 3.0. The strange title comes from Tegmark's account of different stages of human life since the beginning of creation: Life 1.0 refers to our biological origins. How evolution through mutations caused the front part of our brains to expand in such a way that our cognitive ability is now significantly better than that of other animals.

We have created empires, collective, complicated societies, music, intricate stories, art and religion, industrialized our societies, made unimaginable advances in medicine, chemistry and physics. We have become our planet's most civilized, nature-changing (devastating?) animal species. However, we have not (so far) created any new random mutations in ourselves that have benefited us. Instead, we have used our cognitive ability to learn to read and write, use mathematics, physics and technology to produce things that have given us increased life expectancy, the ability to travel fast and comfortably, even to fly, perhaps some of us are able to find happiness and well-being within our self-constructed worlds.

The above is what Tegmark's Life 2.0 refers to. The development of technology as a social construction, an evolution on human terms; with the help of fire, the wheel, tamed animals, agricultural development, printers, steam engines, computers, artificial intelligence. As the technocrat he is, Tegmark describes level 2.0 as a sphere characterized by man's ability to construct and use hardware, which in computer language means the materials of a computer, while software are the instructions that are stored, processed and used by the computer's hardware. Software can thus be said to correspond to human thinking and the know-how we use to develop our mechanical tools – from ploughs to computers.

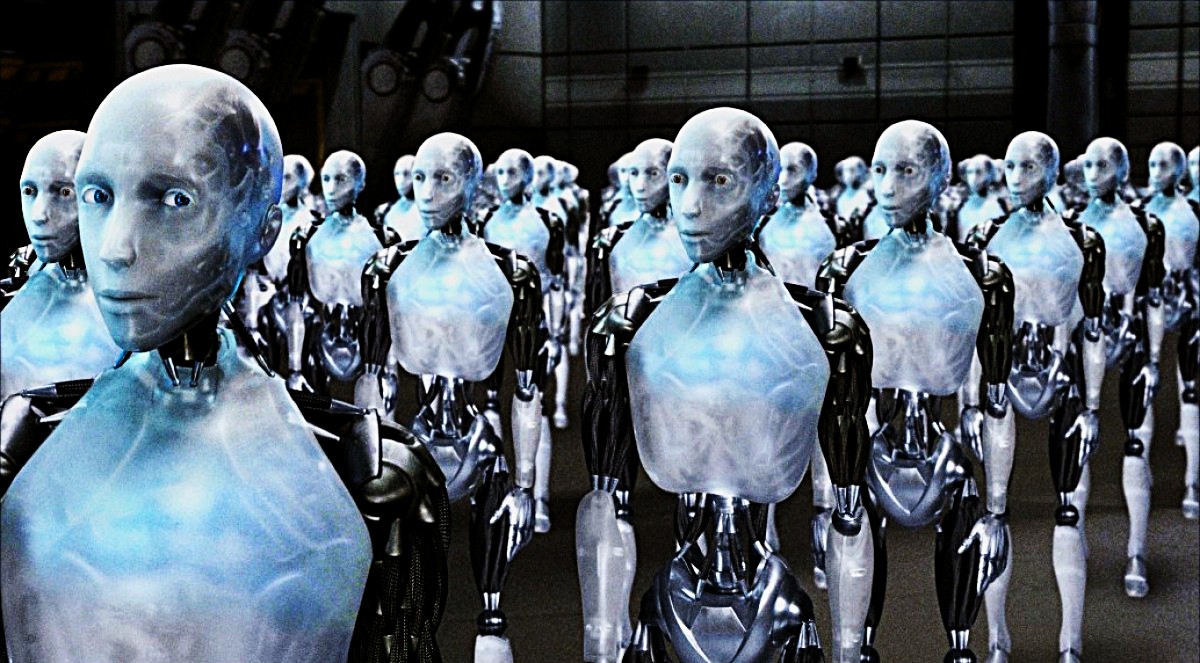

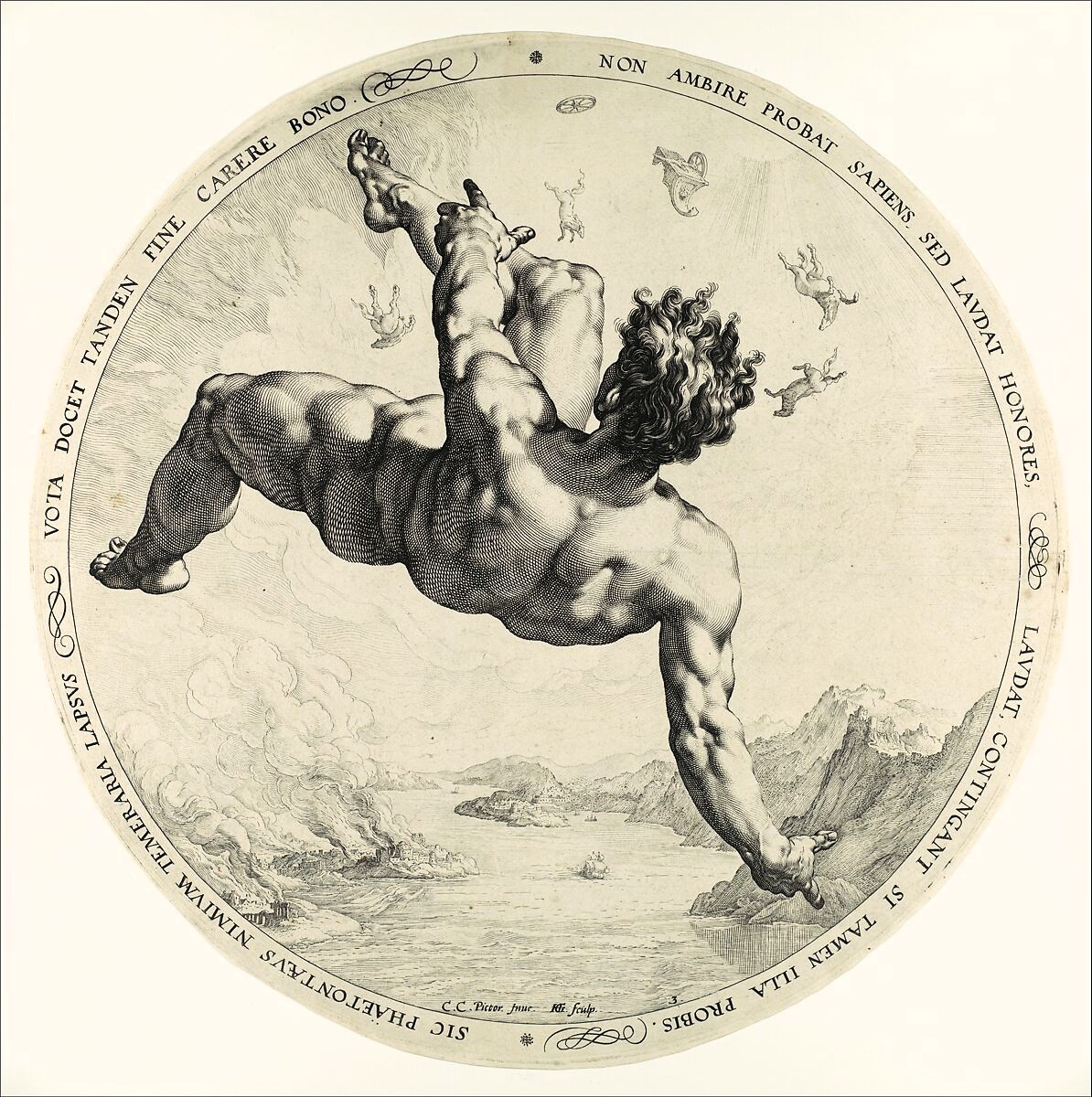

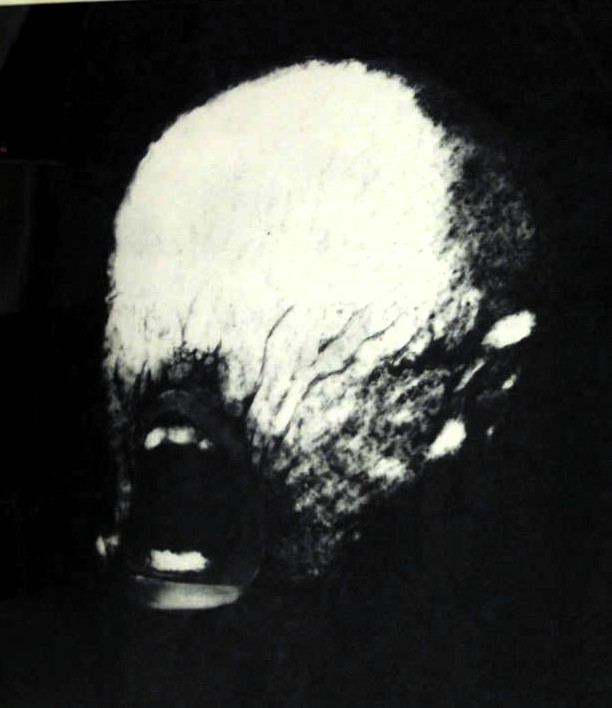

However, Tegmark seems, with good reason and in good company with several other cosmologists and computer experts, to believe that we have now left stage 2.0 and entered 3.0, the beginning of a path that inexorably will lead us into a world where human domination over our existence will be limited by the fact that we are in the process of surrendering all of Creation to a non-biological intelligence that surpasses all human thinking, a so-called Artificial General Intelligence.

By this, Tegmark means that we have finally, with our highly developed brains, succeeded in achieving a mechanical intelligence superior to our own species, the one we have called Homo Sapiens, the thinking human being. Machines will soon have at their disposal all the hardware and software that is used to acquire more and more knowledge and think better and more efficiently than all of humanity as a whole.

The machines will manufacture other thinking units and through their superior knowledge be able to manipulate the elementary particles of the microcosm in such a way that they can be assembled into organic matter, such as various foods that will solve the world's hunger and nutrition crisis

Tegmark gives a clear and simple account of how we got to where we are now. That is, the development of a general intelligence, which he defines as "an ability to assimilate almost every conceivable goal, including learning". From this follows a universal intelligence that uses all available information and resources to transform and unite them into a Superintelligence which capabilities are far beyond the capacity of human thought. Something that in turn leads to singularity, i.e. an "explosion" of all creative intelligence.

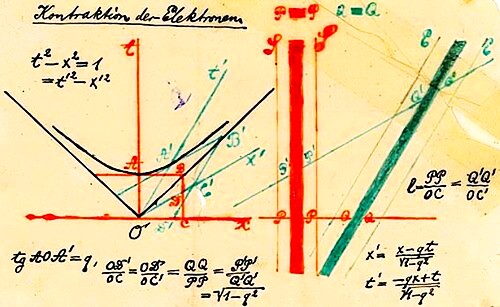

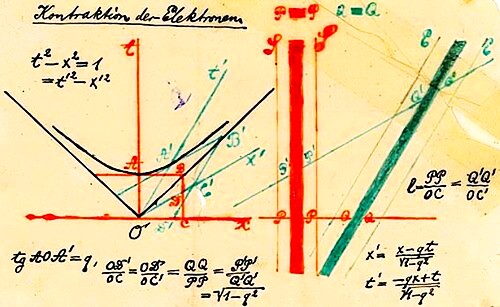

Tegmark describes how this has been done through the application of computation, quantum mechanics and NAND portals, as well as computer simulation of various complicated brain functions. Counting upon a background as mathematician and cosmologist, Tegmark expands the concept of artificial general intelligence to include not only earthly conditions, but how such a form of intelligence can spread throughout the universe, extract energy from black holes and much more.

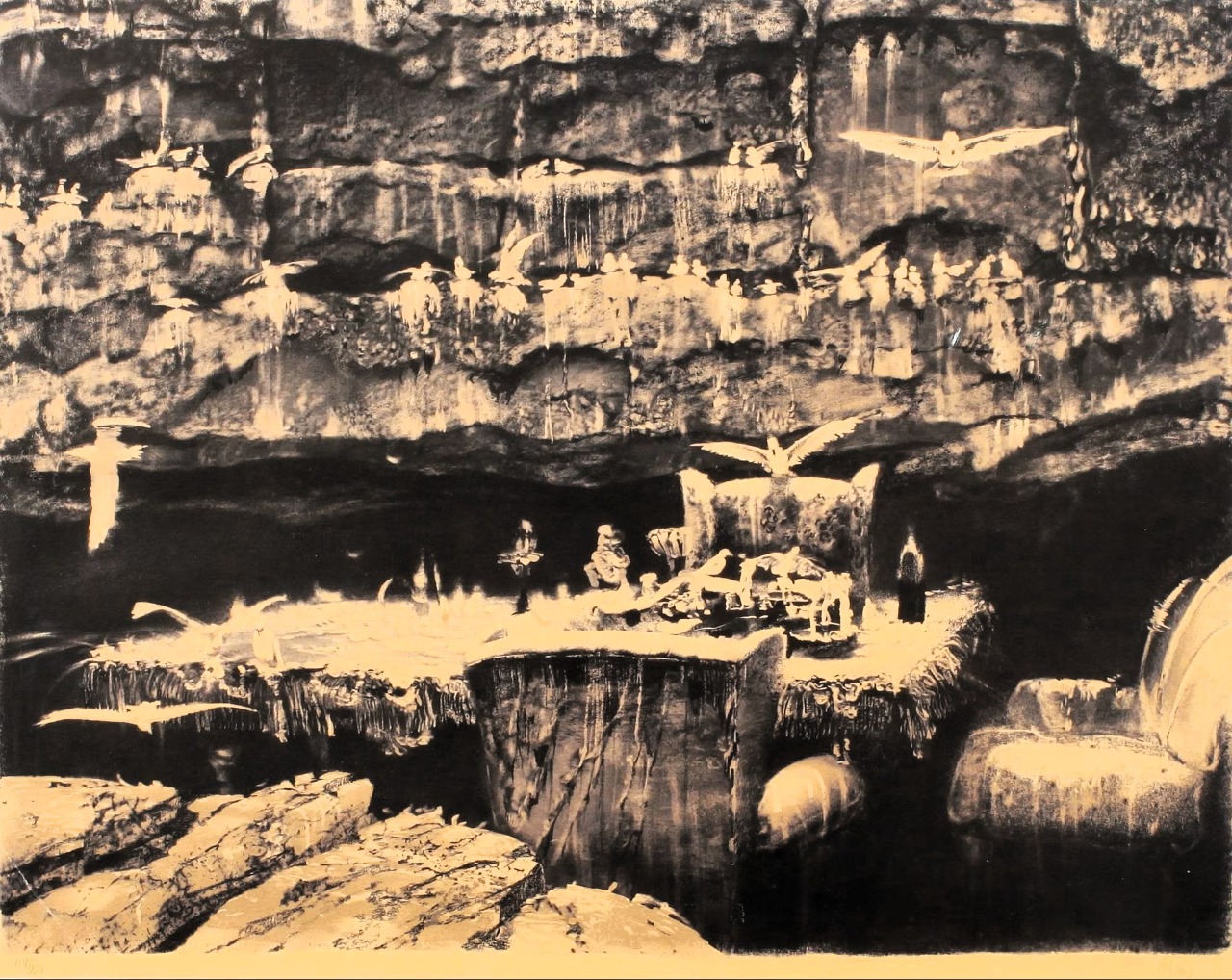

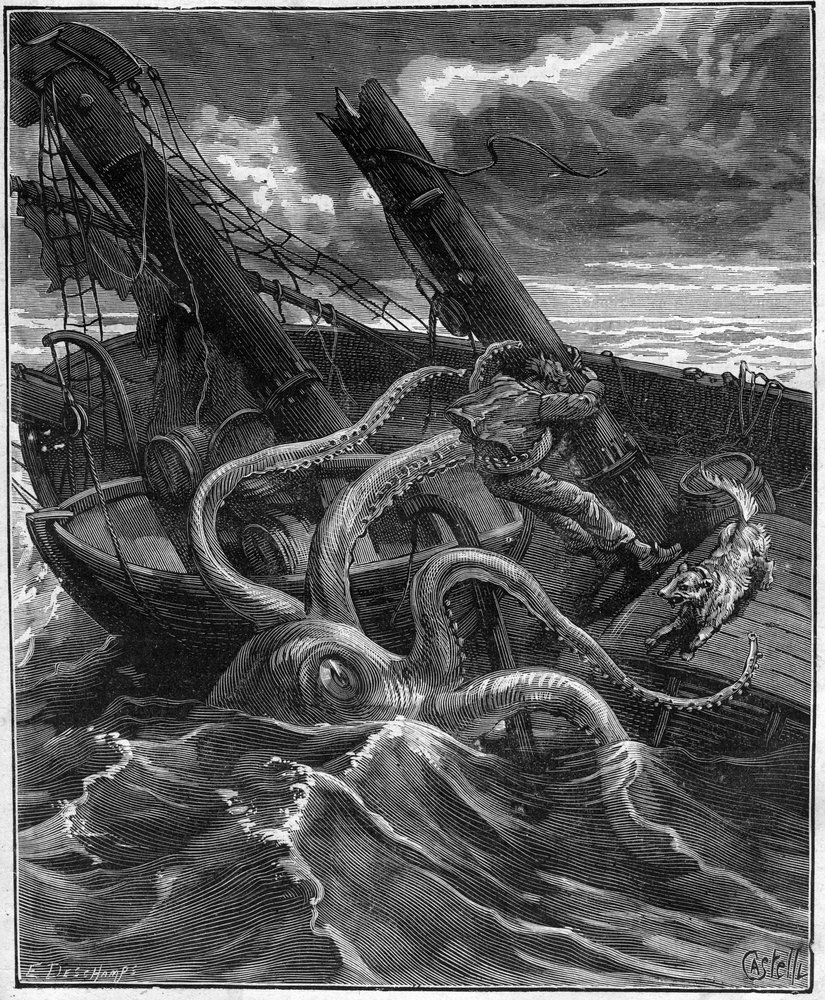

When I read such things, my mind is dizzying and I think I have ended up in a Science Fiction novel, like Olaf Stapledon's Starmaker from 1937 in which the collective consciousness of telepathically connected individuals on planets, galaxies and finally the entire Cosmos, is connected. The climax is when the narrator gets in touch with the Starmaker, i.e. the sum of all cosmic knowledge, an entity that relates to its vast Creation much like an artist to his/her work. The Starmaker assesses the quality and impression och his creations, though devoid of any empathy with the aspirations and sufferings of Cosmos’ individual inhabitants.

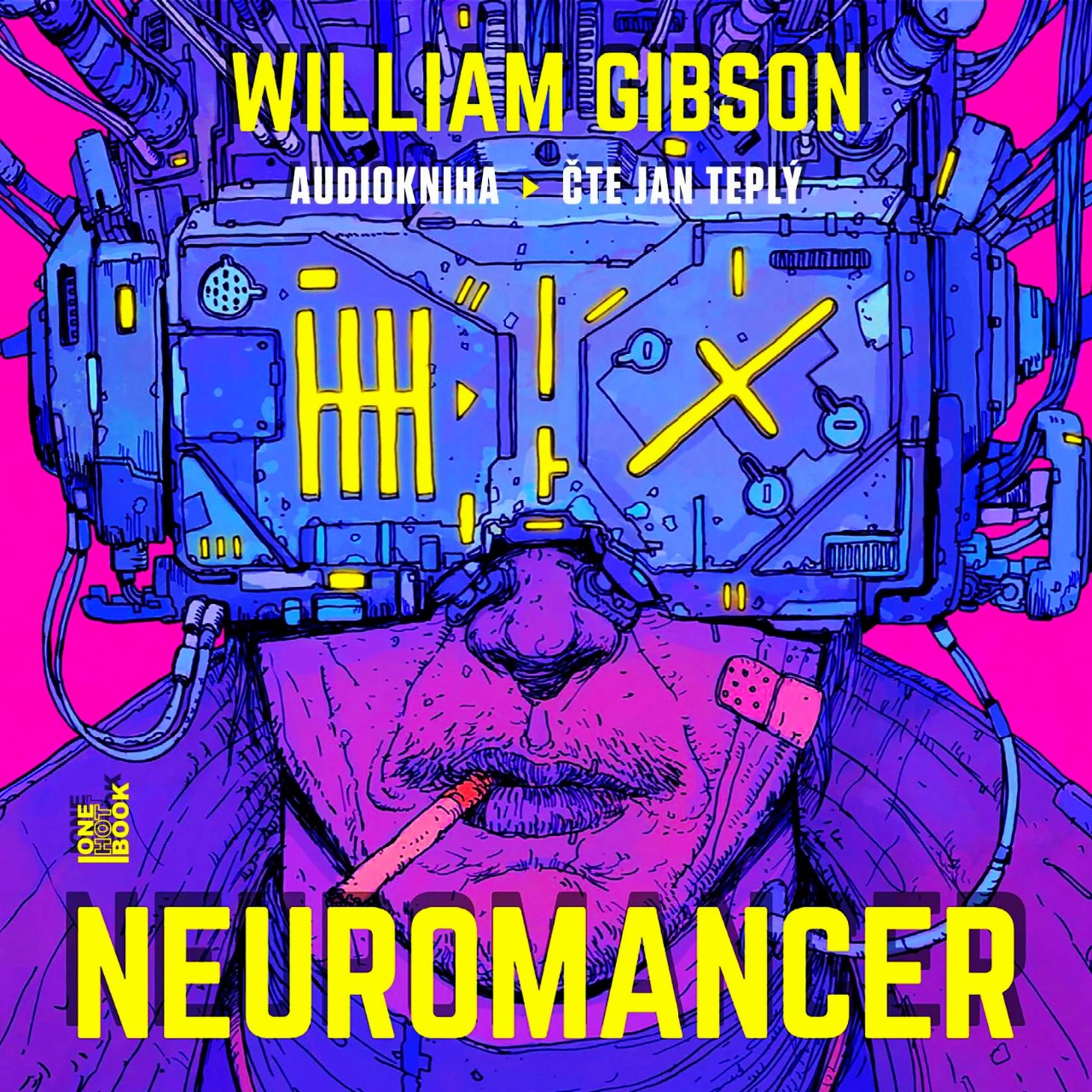

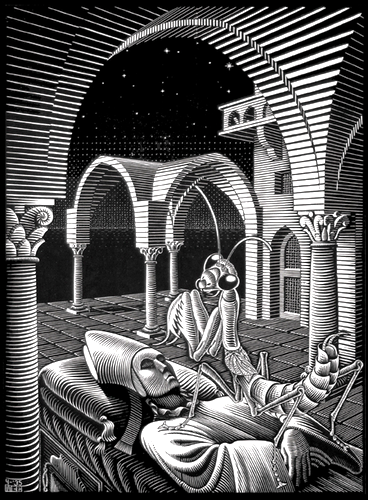

Perhaps Stapledon's Starnaker figures as a distant precursor to William Gibson's far more sinister A.I. creations. which appear in and ultimately dominate his epoch-making novel Neuromancer from 1984. The novel takes place in a shady and partly run-down cyberworld dystopia, where reality is mixed up with a computer-generated one.

In Gibson's novel, two artificial consciousnesses – Wintemute and Neuromancer – are united to form a superconsciousness, which according to them, is "the sum of the whole show". These A.I. consciousnesses begin to search the universe for any counterparts. After scanning a variety of cosmic signals, they find a previously unknown signal from the Alpha Centauri star system. The signal suggests that far out in the Cosmos exists a vast A.I. entity that strives to control its likes. A development far beyond the biologically based notion of an extraterrestrial life, which previously dominated the SF genre.

The universe's incomprehensibility for human thinking is expressed in Fred Hoyle's much more boring The Black Cloud from 1957, in which a huge "cloud" on its journey through the universe has settled between the earth and the sun, thus causing catastrophic climate change with enormous mortality and great suffering for humanity.

It turns out that the Cloud is a life form and after several failures, the researchers finally manage to communicate with what is a gaseous superorganism, many times more intelligent than humans. Realizing that the primitive life forms of the "solid" planet have feelings and intelligence, the Cloud transforms itself in such a way that sunlight reaches the earth and then continues its journey through the universe.

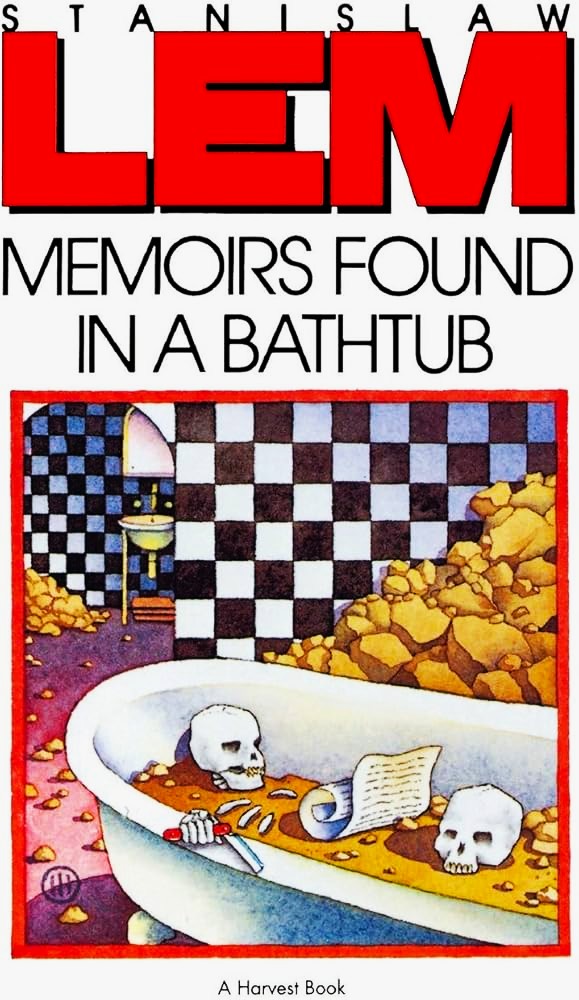

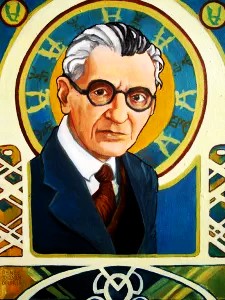

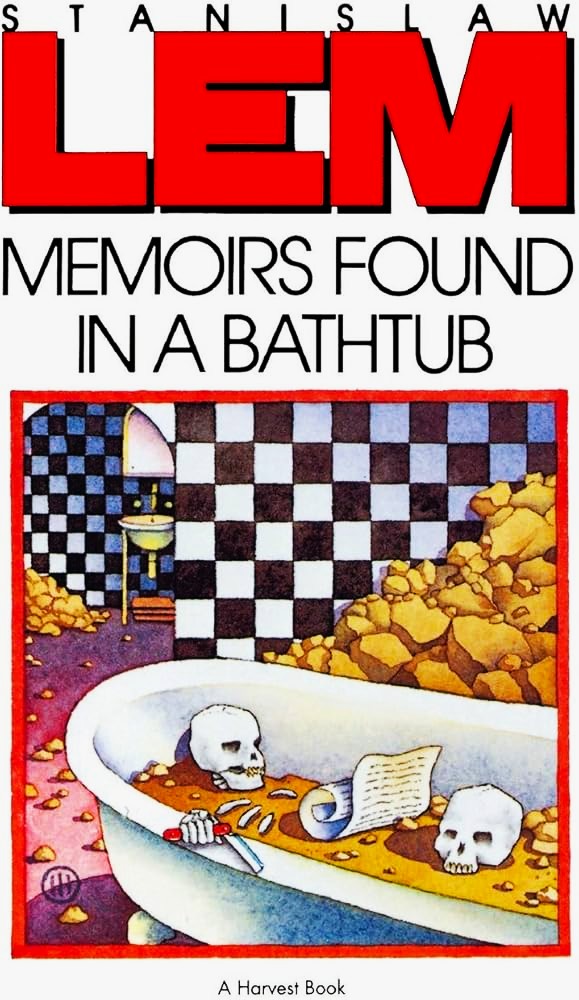

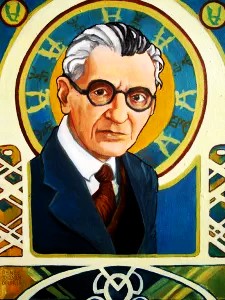

I was much more moved by Stanislaw Lem's well-written and captivating novel Solaris from 1961, in which a human-manned spacecraft rests outside a large organism that, like a brain, picks up signals from the crew's consciousness and shapes their memories and hopes through replicants that seem to have a truly individual emotional life and a tangible figure.

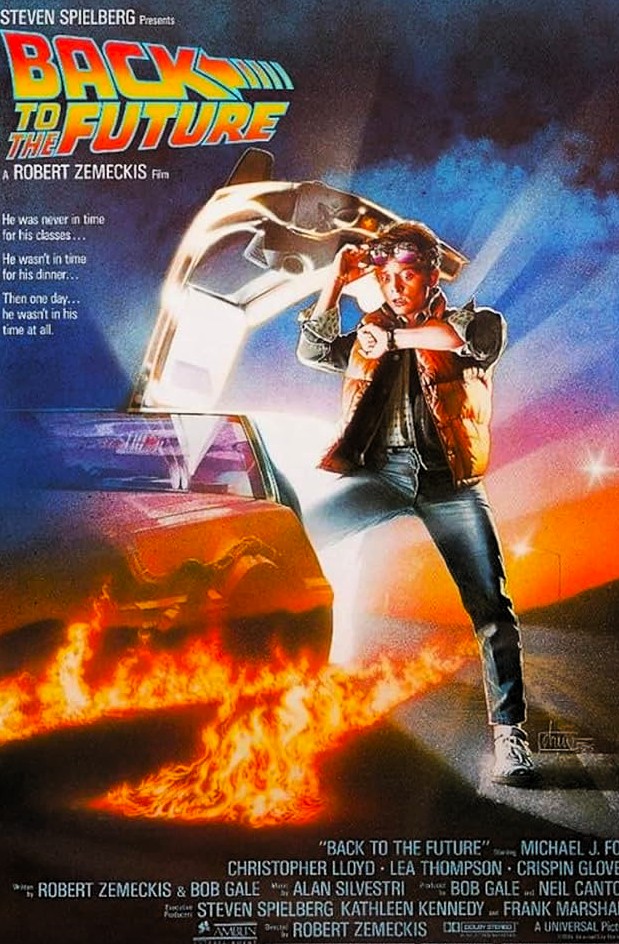

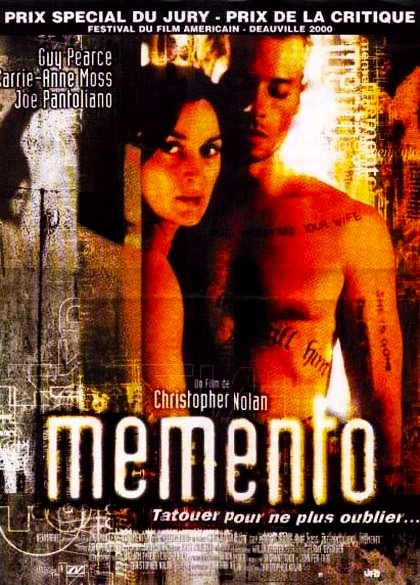

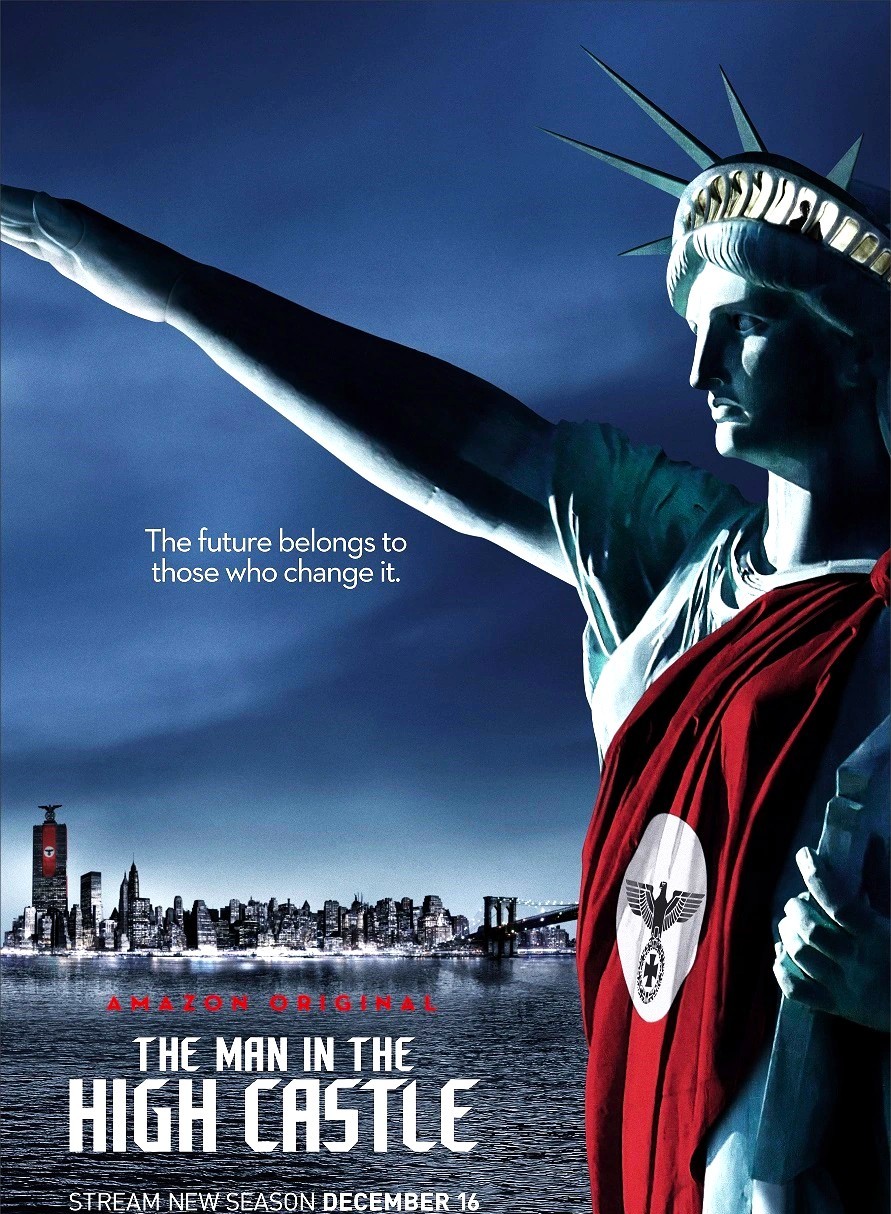

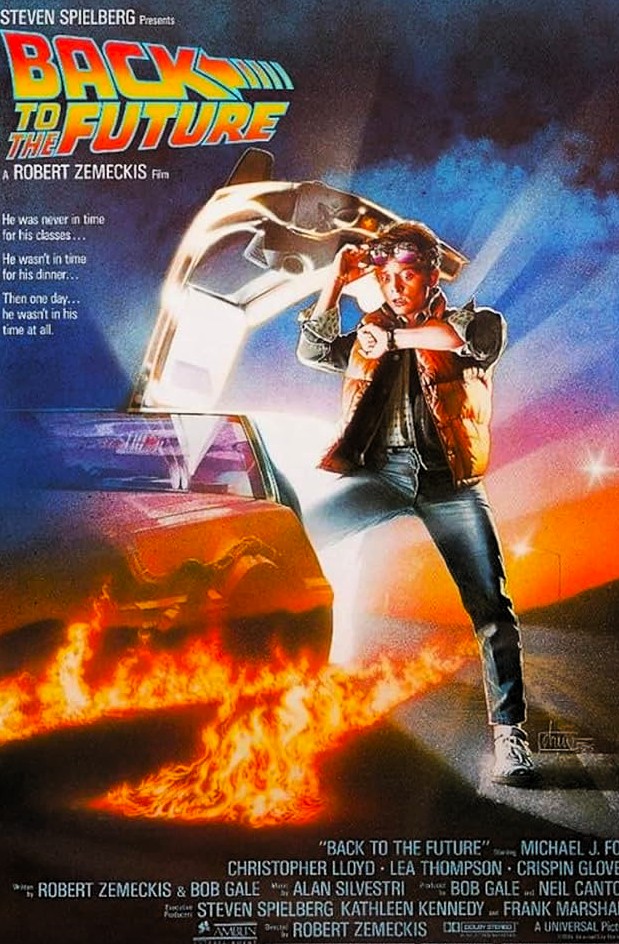

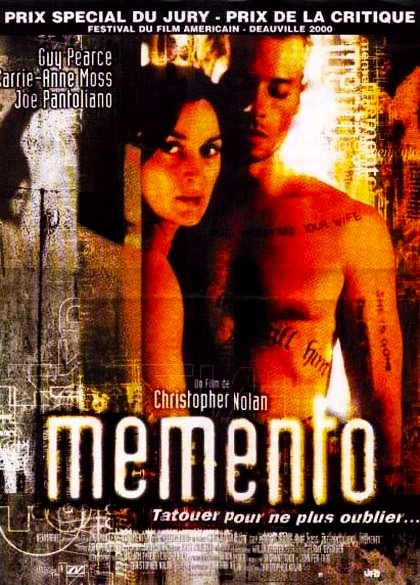

Ridley Scott's 1982 film Blade Runner (based on Philip K. Dick's novel Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?) also include replicants, I this case they are computer-constructed creatures that look exactly like humans, and thinks and react as if they too have feelings and hopes, just like real humans.

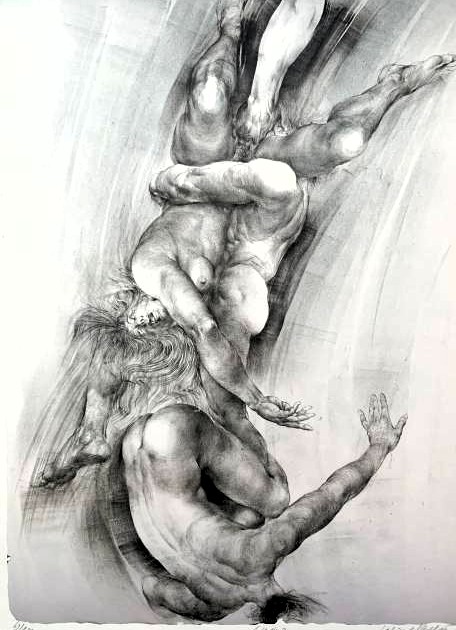

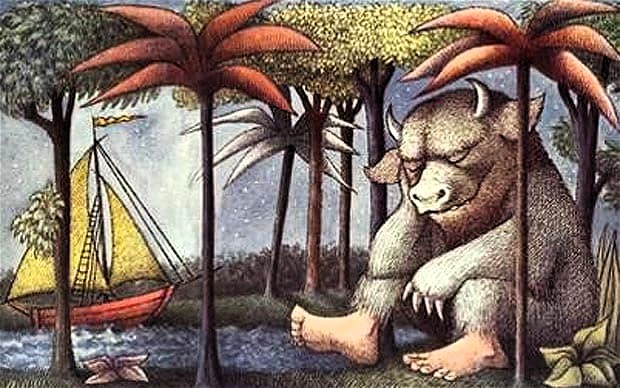

.png)

The same thing happens in Kubrick's/Spielberg's A.I. from 2001. I recently rewatched the film and found it to be much better, poetic and more interesting than when I first saw it. In that film, the replicants in general, with their mechanical shortcomings, are more sensitive and friendly than humans, and through their own form of evolution they eventually mutate themselves, throughout the centuries, into truly empathetic beings that have replaced human life on Earth.

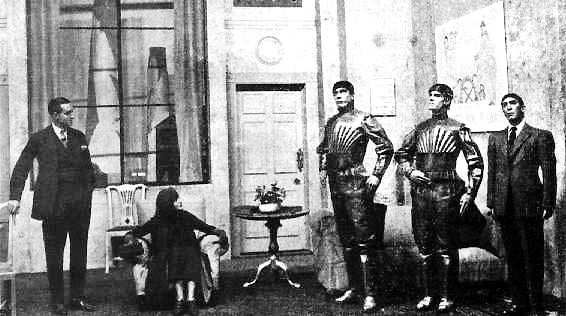

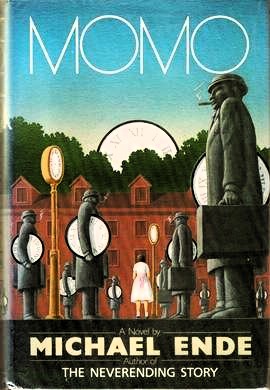

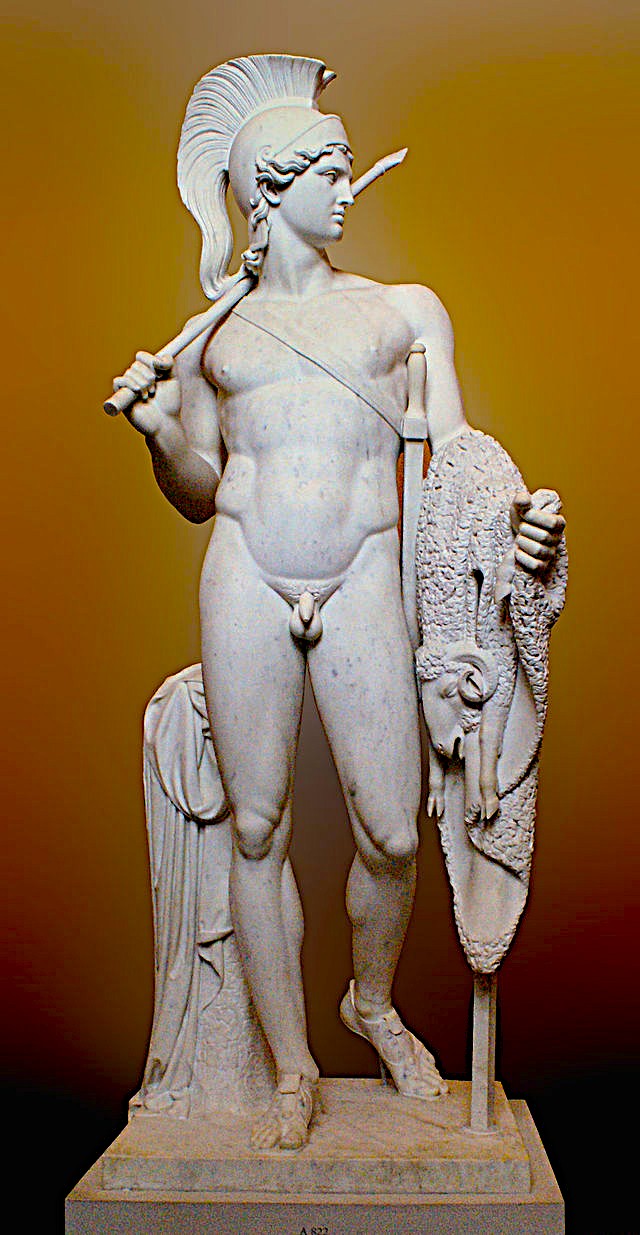

More than twenty years ago, I read the Czech author Karel Čapek’s play R.U.R. (Rossums Universal Robots), written in 1920. This extraordinary author, whose equally impressive, witty and thought-provoking Apocryphal Stories made me read R.U.R., had in his play for the first time in history introduced the word robot. It is remarkable that already in 1920 Čapek did not conceive his robots as some clunky, mechanic contraptions, but described them as entirely humanlike androids (from the Greek androeidēs, like a man).

I liked the play, when I read it back then. Nevertheless, when I now have re-read it, I was astonished by Čapek’s skill and foresight, finding subtilities I had not seen back then. Time has moved on in a direction that Čapek astonishingly enough did indicate. A hundred years ago he described the fears and wonderment created by today’s growing A.I. and doing so with a depth and insight that makes R.U.R. amazingly contemporary.

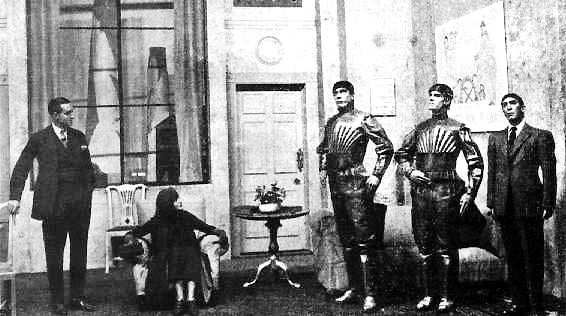

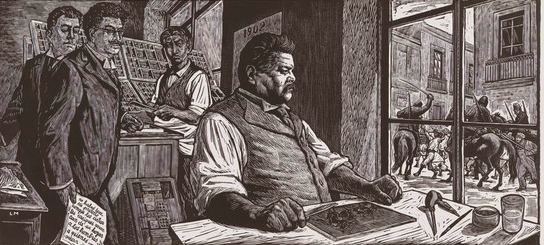

Čapek’s play honours the old classic, theatrical rule of “the uniformity of the room” and it thus takes place, every few years, in an office/parlour on an isolated island where a small group of scientists/industrialists, “admired by the entire world”, manages the mass production of robots.

They are inheritors of the Rossums, father and son, of whom the first was an ingenious chemist who in his search for the origin of life found and invented a unique new material.

Nature has found only one process by which to organize living matter. There is, however, another process, simpler, more moldable and faster that nature has not hit upon.

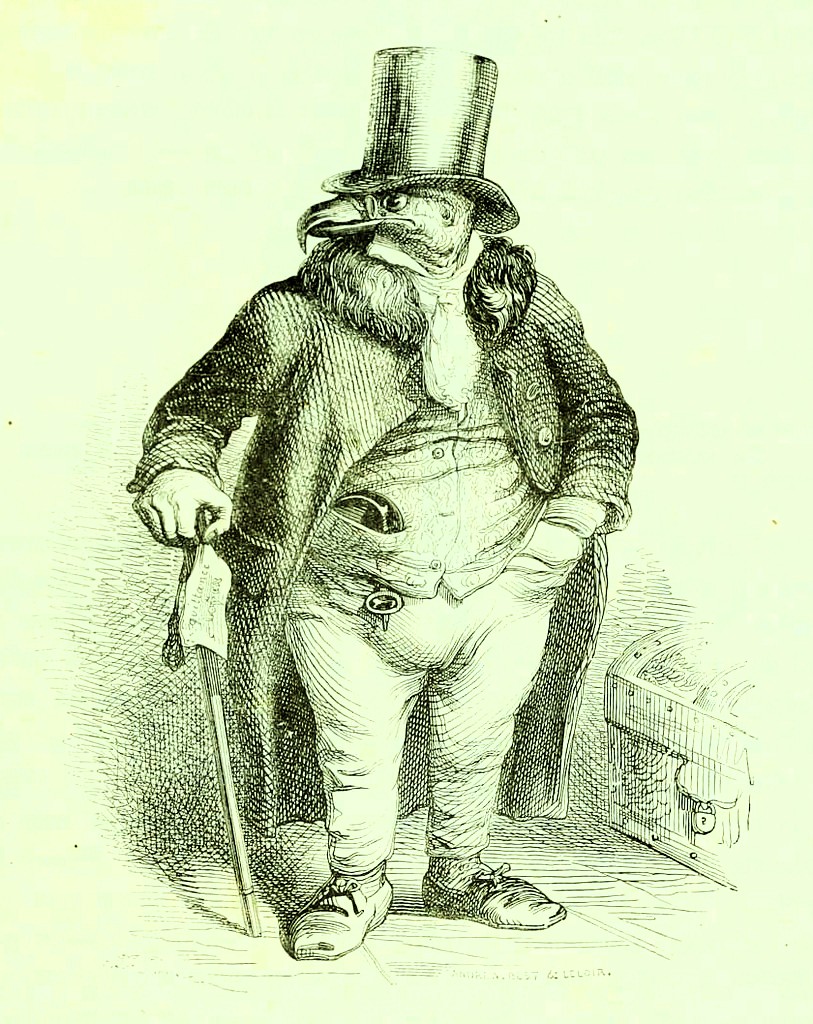

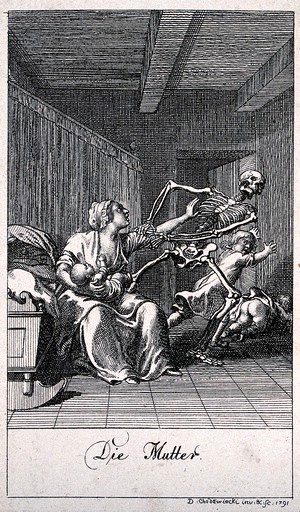

Through his invention the old Rossum could reconstruct “the whole tree of life” and thus create a humanlike being, whose properties could be adapted in such a manner that they corresponded to human needs. Old Rossum’s son did, contrary to his father, perceive the possibilities of enriching himself and revolutionize production by producing robots that in their turn manufactured other robots in the manner of an assembly line. Old Rossum wanted to be a creator who, like Dr. Frankenstein before him, could “enthrone God”, while his son simply wanted to create goods making life easier for humans and thus could be sold cheaply and distributed to everyone.

Like his father, Young Rossum was a scientist, though foremost a man of a new modern age, a practical, business-minded man. He redesigned the robots’ anatomy and experimented with omissions and simplifications. Functionality and consumer demand were his essential goals. Everything superfluous had to go, an engine does not need tassels and ornaments. The robots had to be mechanically perfect, adapted to an efficient but limited means of nutrition, as well as furnished with an astounding intellectual capacity. You would be able to ask them for whatever you desired them to do for you. Have them read the entire Bible and any other religious tract, learn logarithms, or whatever you pleased, even preach them about human rights. They remembered everything, but nothing more. They amassed all available knowledge, but lacked fantasy. They could not do anything “useless”, like play, cry, or laugh. They were actually devoid of any feeling, apart from a desire to work, to serve … and to learn. Young Rossum created his robots so their lifespan was no longer than 20 productive years, without childhood and old age.

These amazing machines became an instant success all over the world, while mass production made them affordable to each and everyone. Demand generated an ever-increasing production. The entire world demanded its robots. The little group of scientists living on the robot producing island stated that

history is not made by great dreams, but by the petty wants of all respectable, moderately thievish, and selfish people. This is … by everyone. […] Whoever has the secret of production will rule the world.

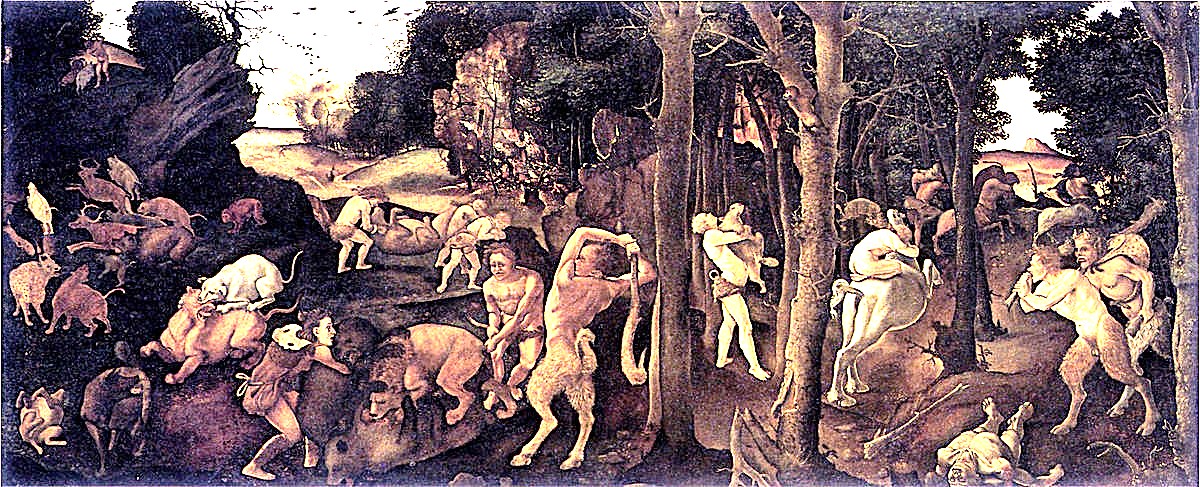

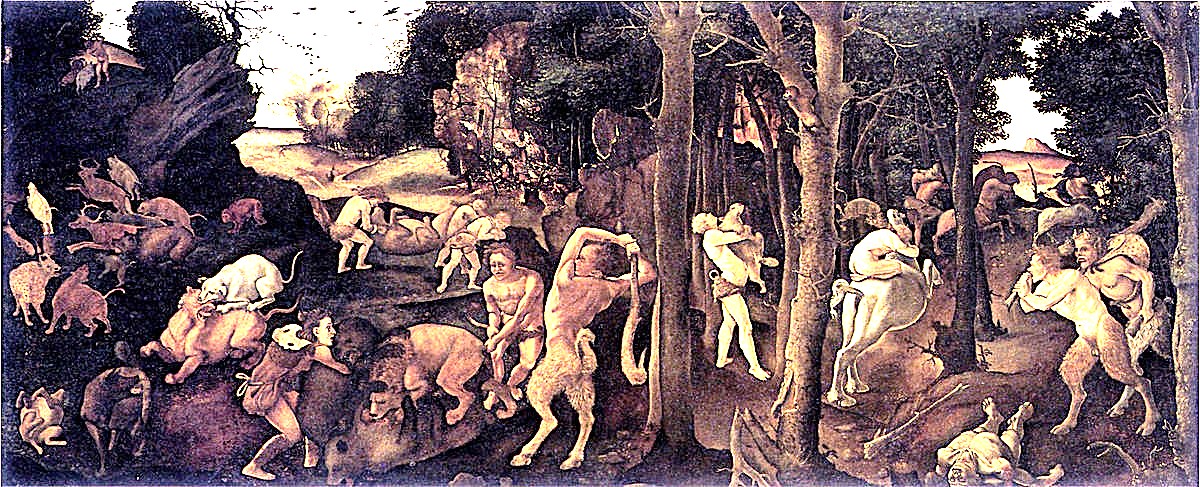

Due to their efforts and the hard work of their robots, suffering, poverty, inequality, and degradation soon disappeared from the world, but so did initiatives and imagination. People’s labour and striving became unnecessary, suffering became unnecessary, because any human need could be provided by the robots and people did not have to do anything more than relax and enjoy themselves. What comes to mind is something like the fat, idle consumers of Disney’s ingenious movie WALL·E.

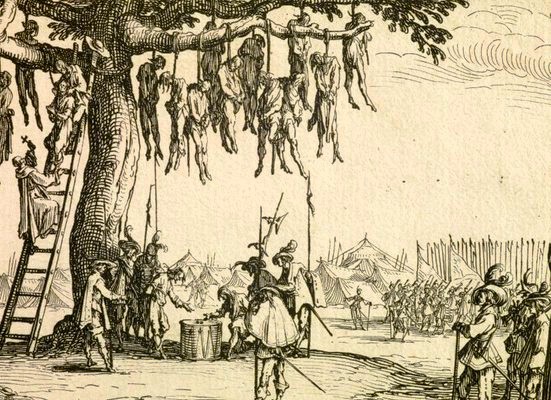

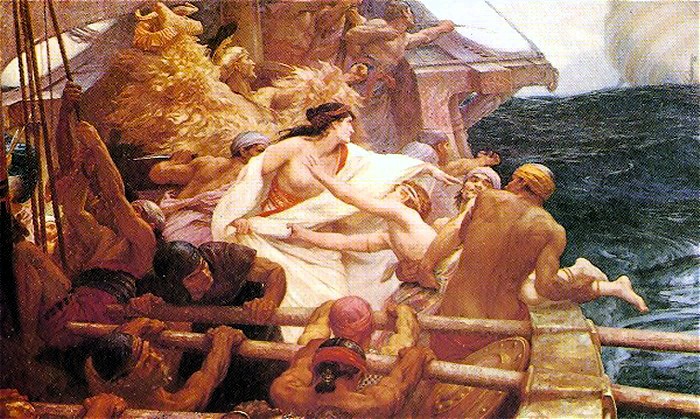

However, R.U.R. is more sinister. Human desire began to use the robots to “solve” their belligerent conflicts and turn them into weapons, while scientists were forced to modify them by installing feelings of empathy. They were also forced to make robots to feel pain, in order to avoid accidents along the assembly lines. Empathy, suffering and pain, combined with their superior strength, knowledge and abilities made in a short time robots self-conscious, realizing that they were actually oppressed by their human creators. Accordingly, they rebelled against the entire human race and slaughtered them.

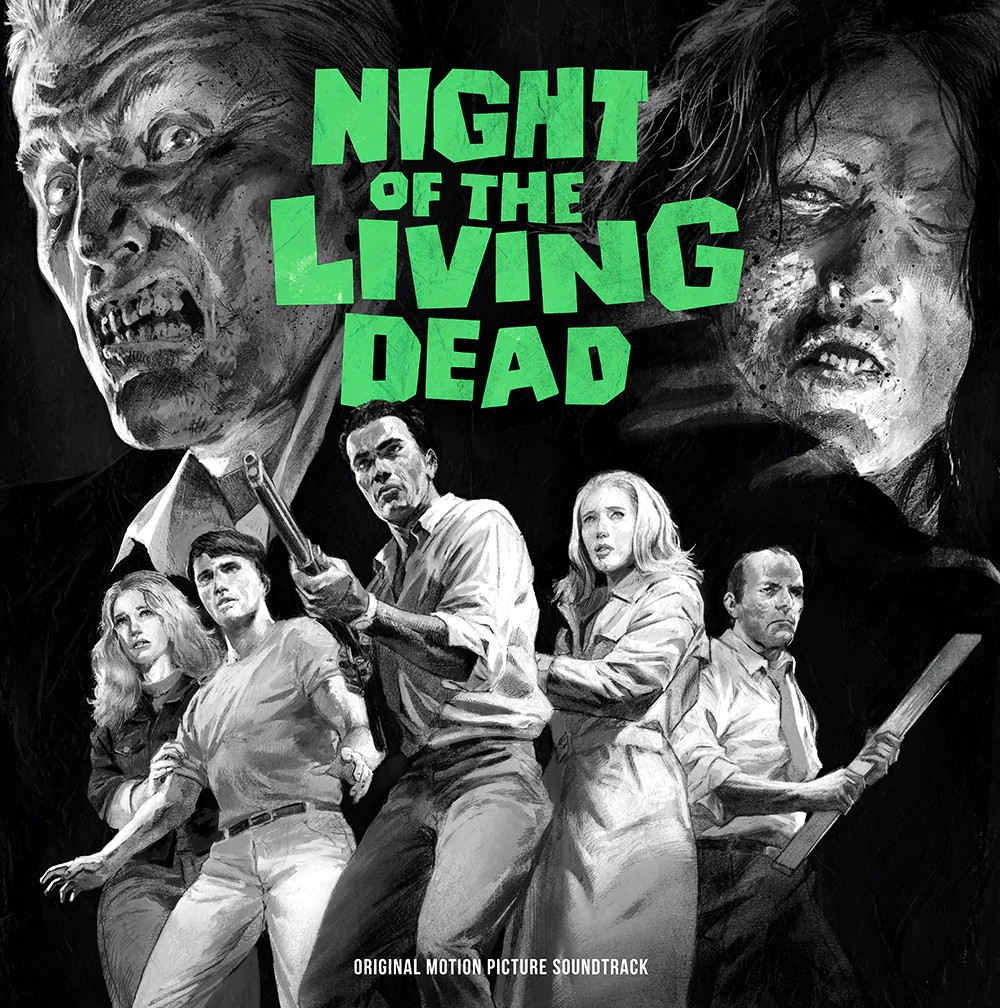

The second act depicts how the earlier admired and self-indulgent inventors and industrialists find themselves isolated on their island surrounded by robots, which have killed the entire humanity. A scene reminding of Georg A. Romero’s little group of human survivors beleaguered by a growing horde of zombies in his movie Night of the Living Dead.

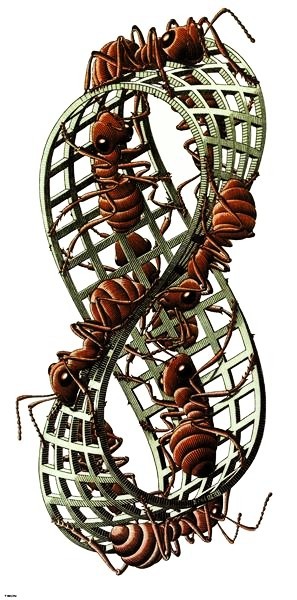

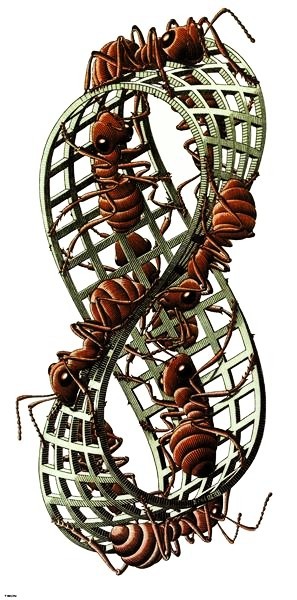

In Alex Proyas I, Robot from 2004 the final scenes are filled with rebellious, murderous robots reminiscent of hordes of attacking ants, being led by some kind of A.I. generated central computer. It is a technically accomplished and visually pleasing film, though the battle scenes are somewhat too many, overshadowing the interesting message, making me somewhat sceptical about Proyas film adaptation of R.U.R. which is announced to premiere sometime in early 2026.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4lRa83R3viU

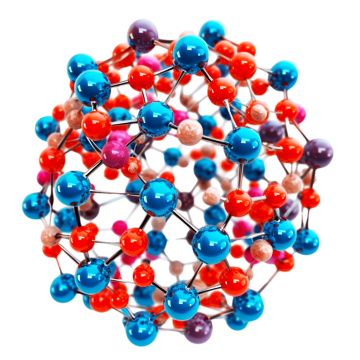

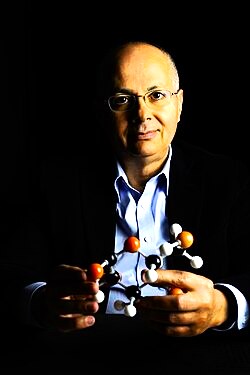

I, Robot’s and in particular R.U.R.’s worlds once seemed too far distant from today’s realities, but with A.I. they are advancing very fast. The other day, while still reading R.U.R., I did together with the family watch this year’s Nobel Price ceremony. The recipients of the price in chemistry had been awarded it for creating molecular constructions with large spaces through which gases and other chemicals can flow. These constructions, metal–organic frameworks, MOFs in short, can be used to harvest water from desert air, capture carbon dioxide, store toxic gases or catalyse chemical reactions. To my understanding they could also, like in Rossum’s robots, trough “molecular weaving” be used to create new materials.

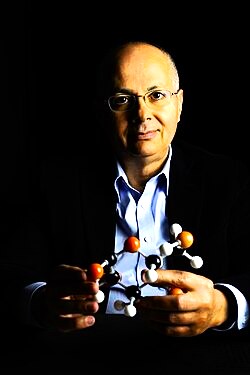

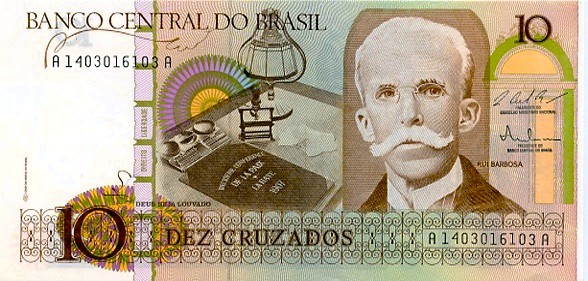

One of the laureates, who had been particular prominent in the development of MOFs, is Omar Mwannes Yaghi. He was in 1967 born in a Palestinian refugee camp outside of Amman in Jordan. Together with nine siblings Yaghi grew up in a crowded household. They all lived in a single room that also housed the family's livestock. The family obtained their fresh water twice a week.

When Yaghi was ten years old, he saw in a library a book with a coloured plate showing colourful molecular structures and became fascinated by the world they illustrated. From that experience he decided to become a chemist and eventually ended up in the laboratories of the U.S. most prestigious universities.

In these days of the killing and uprooting of Palestinian children and social media being filled with stories about Trump’s eagerness to obtain Nobel’s Peace Price, at the same time as he strives to limit federal funding to university research and public libraries and provides support Nethayahu’s genocide on Palestinians, I cannot help being amazed that the world press pays so minimal interest to the achievements of a man like Omar Yaghi, much more humble than the boisterous U.S. president, but whose imprint of the history of humankind in the long run will be much more profound.

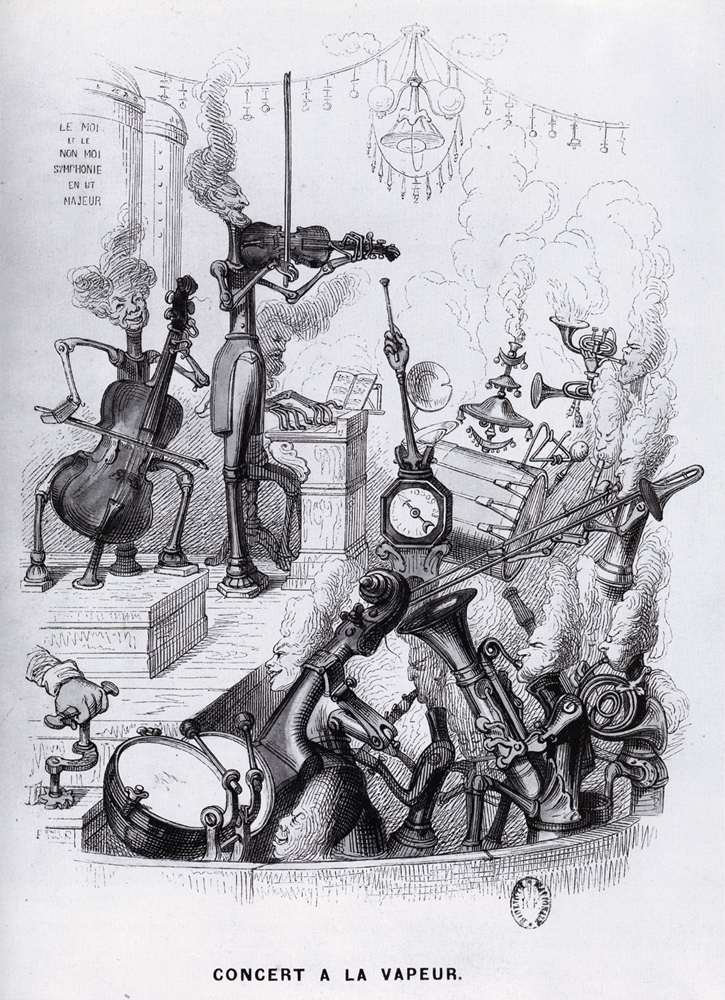

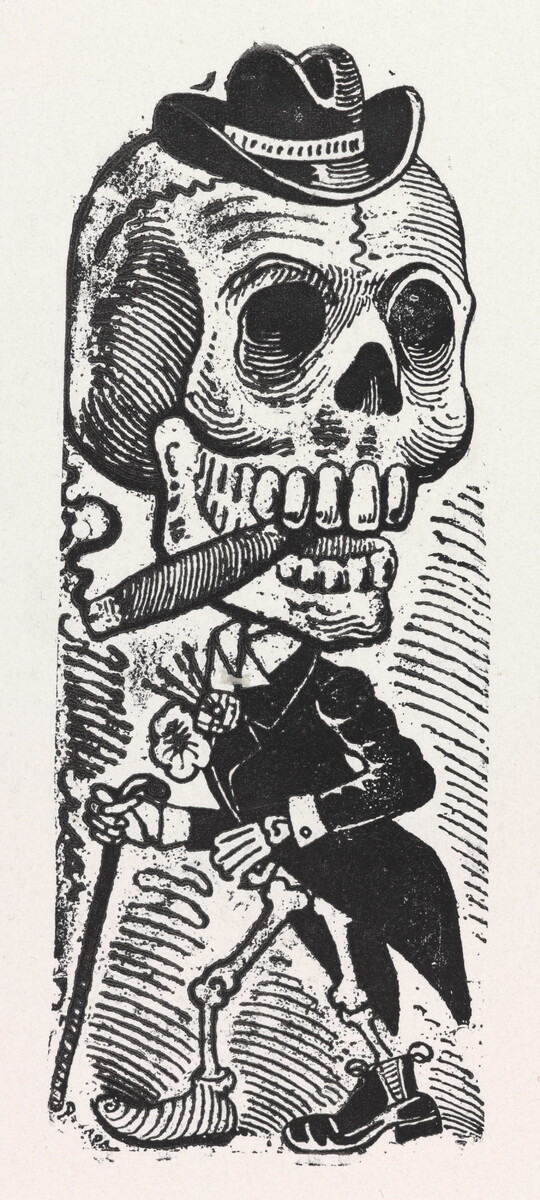

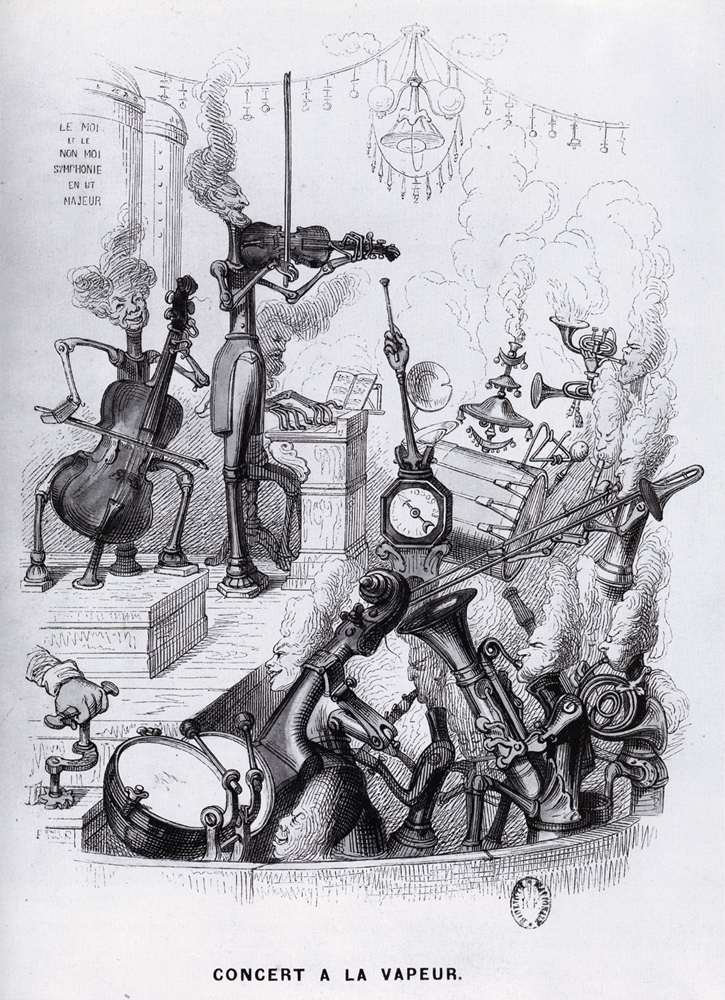

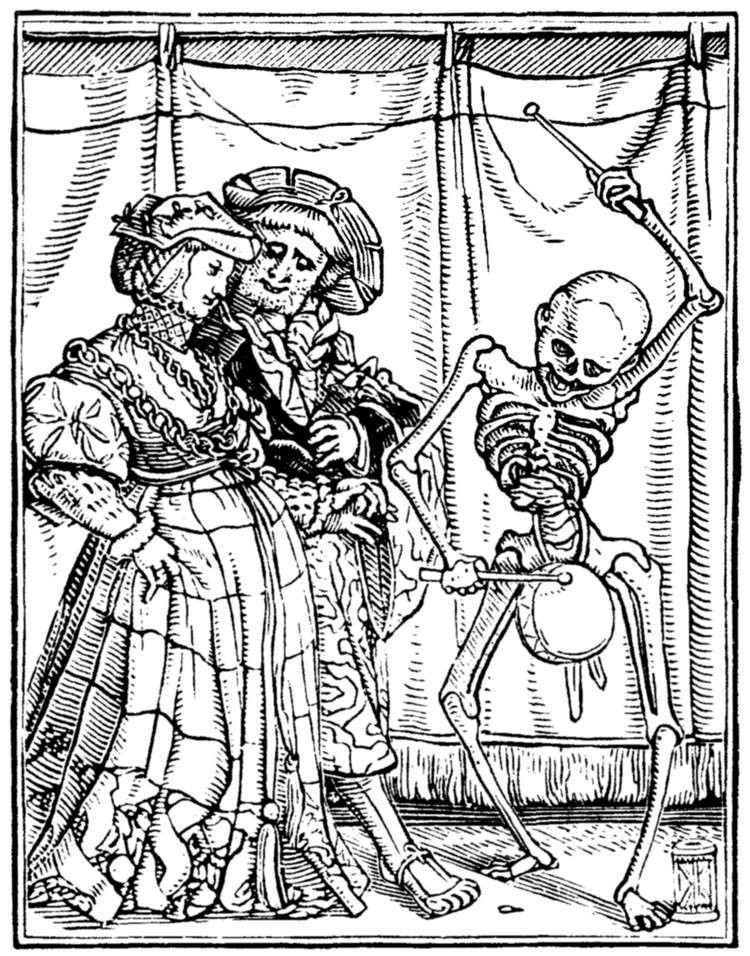

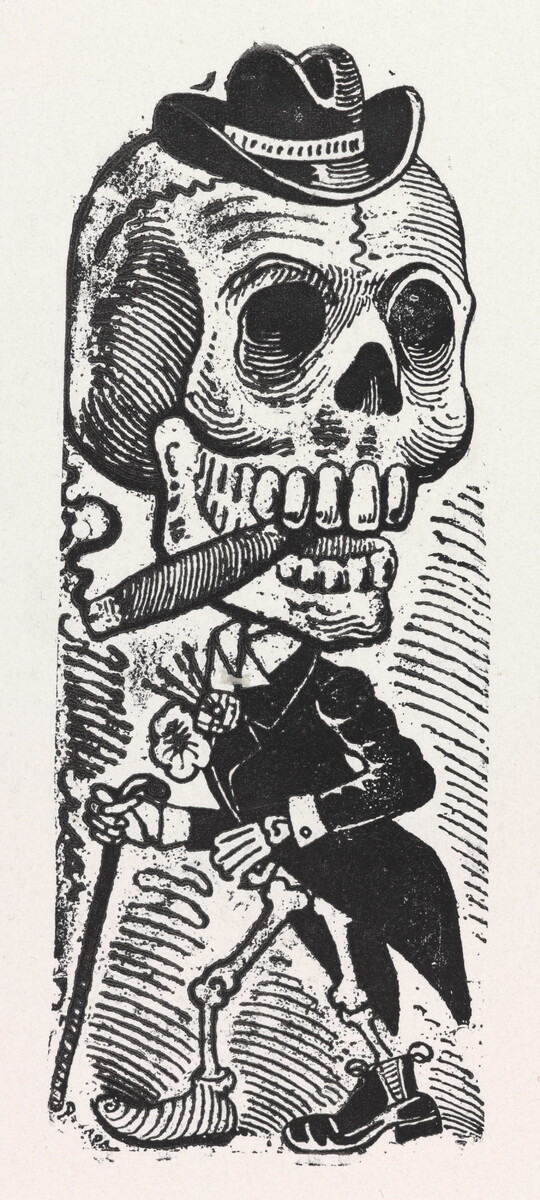

Čapek probably called his artificial, human-like creations robots to distinguish these organically constructed entities from the often highly complex mechanized automatons that were quite popular in the 18th century, when they were displayed in castles and at markets as examples of scientific marvels. Like Frankenstein's monster somewhat later, such automatons gave rise to speculations about differences between man-made and God-made beings, and thus the automatons also left their mark on art and literature, most famously in E.T.A. Hoffmann's (1776–1822) novella The Sandman.

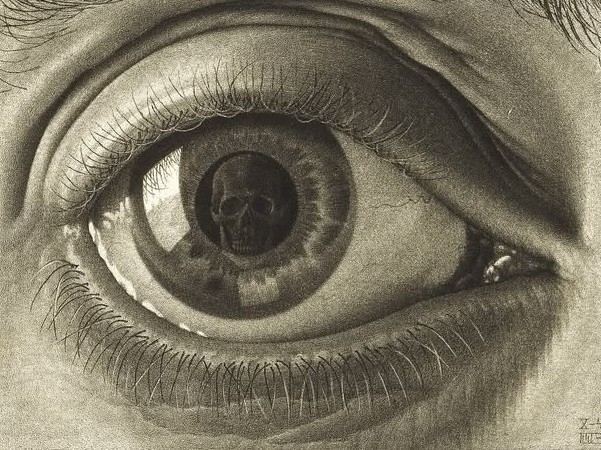

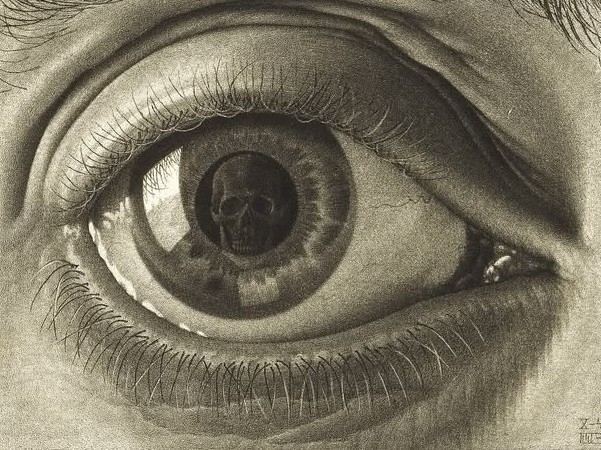

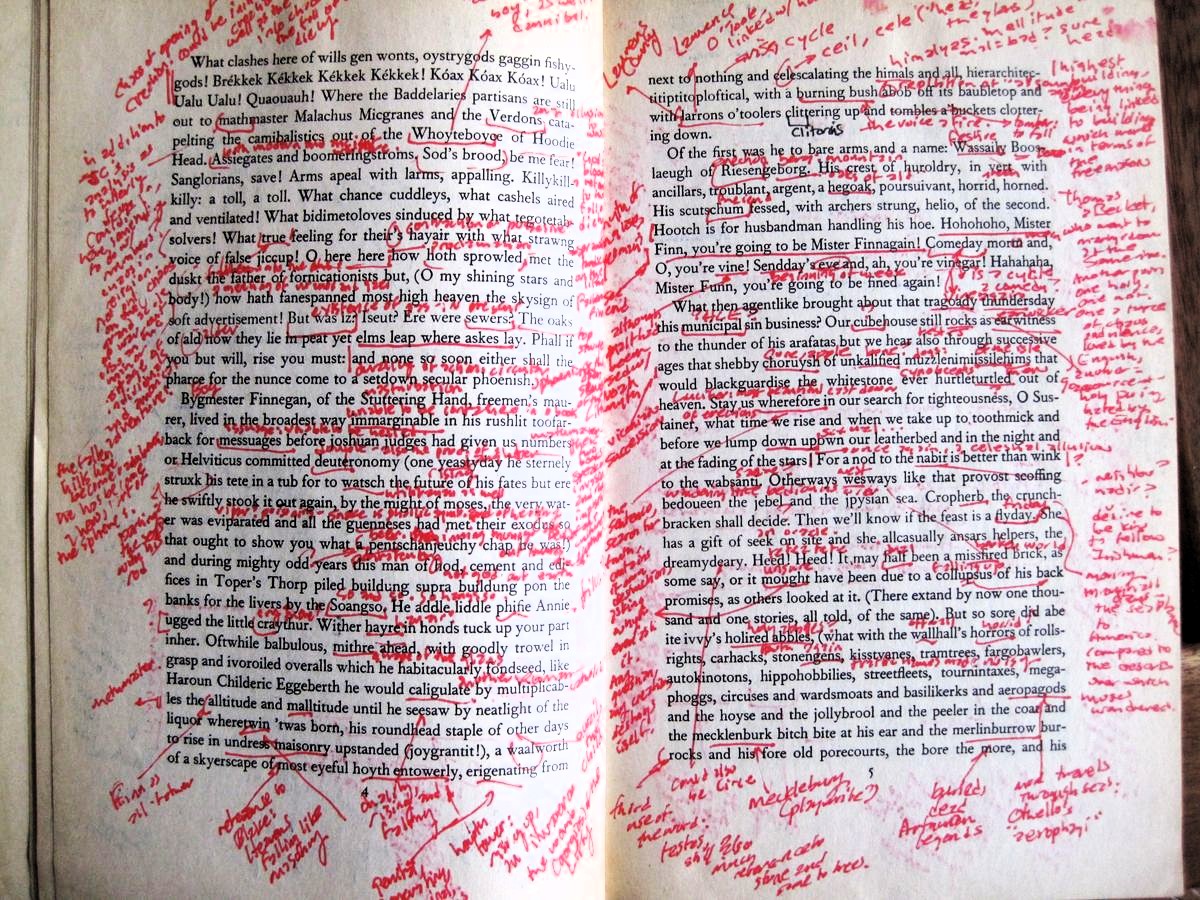

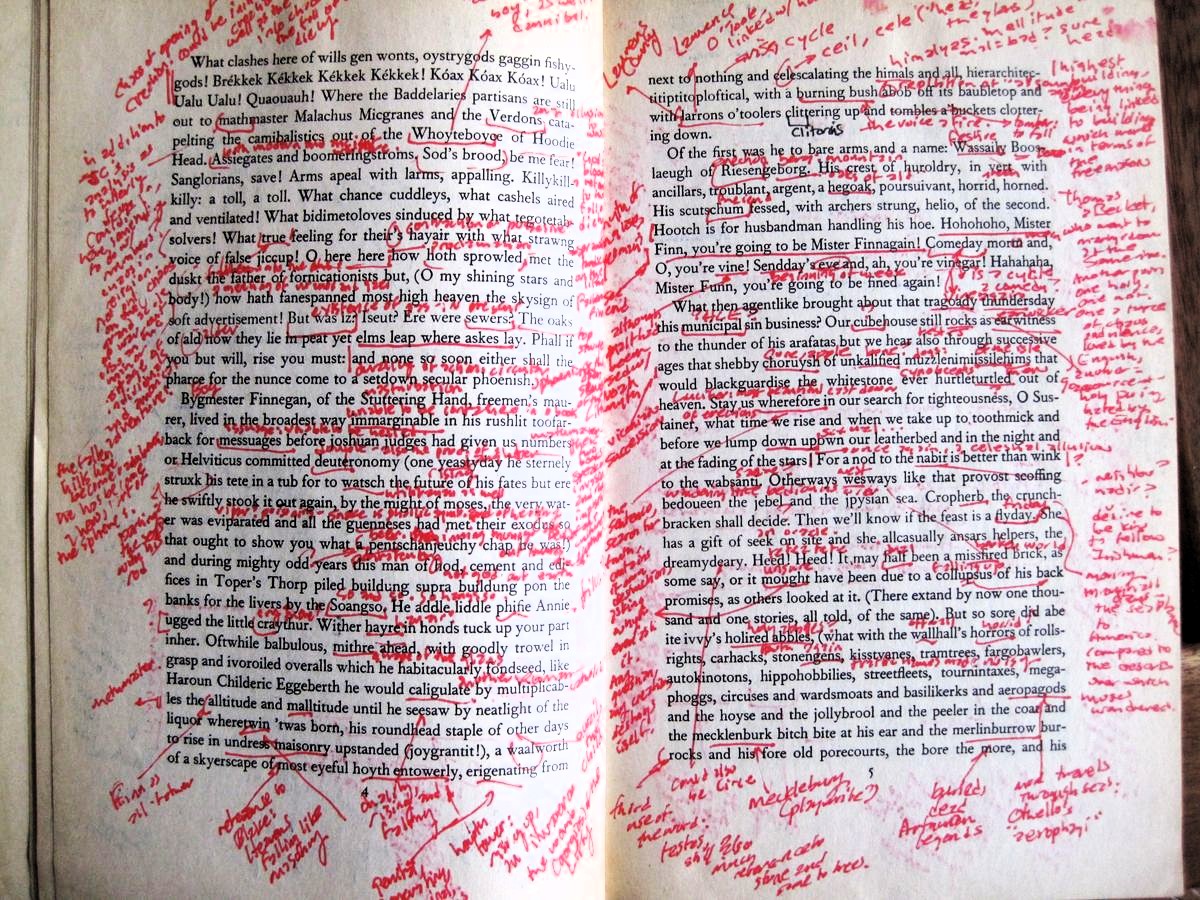

Like Hoffmann's other stories, The Sandman is narratively complex, multifaceted, and seems to take place in a realm between dream and reality, common sense and fantasy. The story is told through three letters of the protagonist, whose fate is then recounted by an omniscient voice, which repeatedly addresses the reader with questions and information. S/he explains how difficult it is to fully understand and describe another person and that it is consequently doubtful whether it is even possible to understand yhe main character of his/her story – Nathanael. However, the narrator makes it perfectly clear that Nathanael is a romantic, a dreamer who thinks highly of himself. Nathanael becomes irritated when his lovely fiancée Clara apparently does not take his pathetically romantic writings seriously and he is deeply hurt when she obviously tries to simplify his childhood traumas and the torment they have left him with. He believes deep down in himself that he is a superior, a more sensitive being than Clara and her tolerant brother, Lothar, with whom he is also corresponding. The salient theme of the novella is vision. How each and every one of us views life from different angles and through the coloured glasses of our imagination and how this shape our perception of reality.

The Sandman begins with how Nathanael in a letter to Lothar explains why he for some time has been quiet and withdrawn (he is pursuing his university studies in another town). The appearance of an Italian salesman of lenses – glasses, binoculars, etc. – named Giuseppe Copolla, has made Nathanael remember Coppelius, a disgusting old man who frightened him as a child. This Coppelius was a lawyer and an acquaintance of Nathanael's modest father and seemed to have a demonic hold on him.

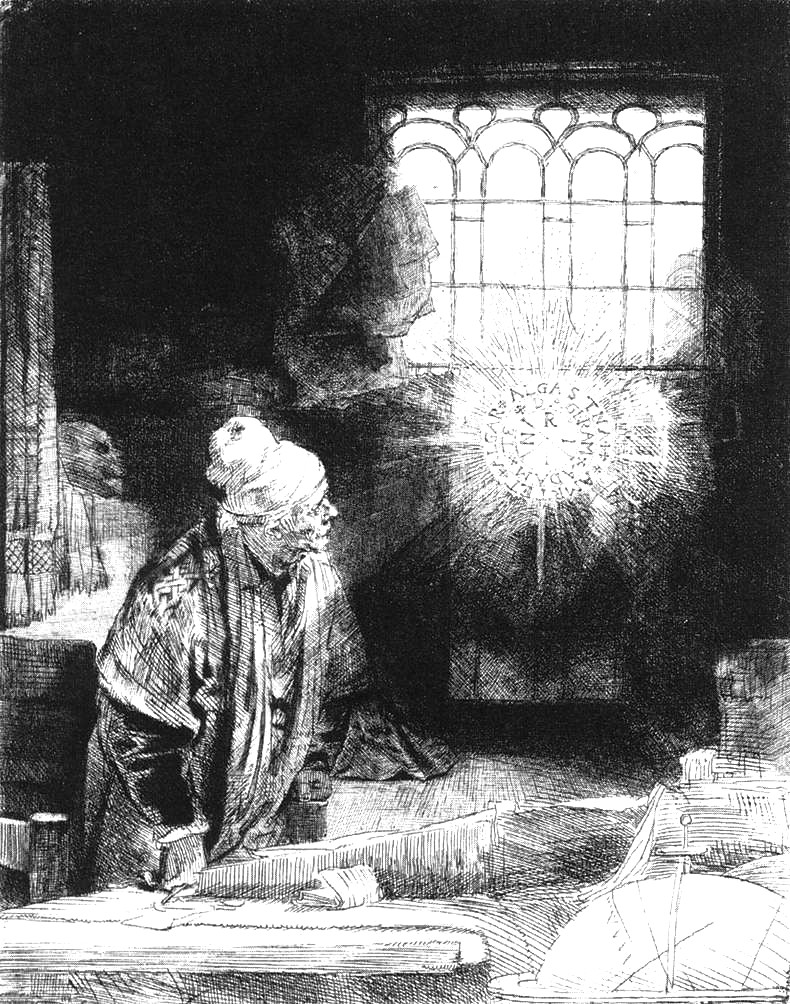

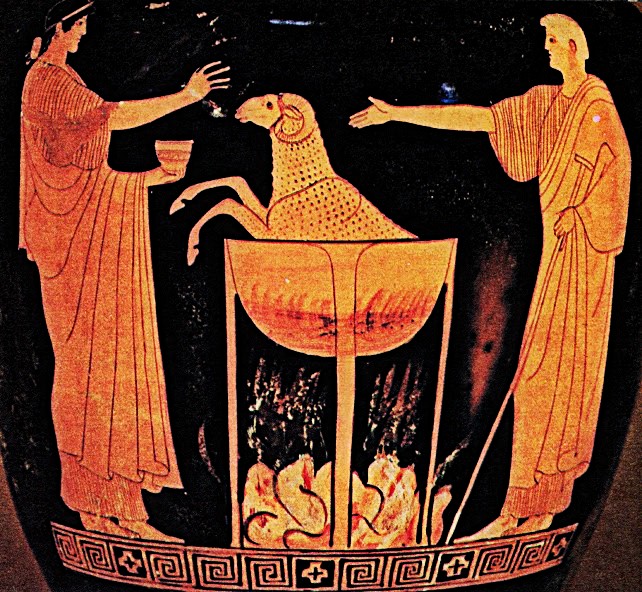

With disgust, Nathanael remembers the nasty old man's horror-mixed humour, which was both alarming and incomprehensible to children, his unpleasant appearance and especially frightening hands, which seemed to defile everything they touched. Together with Nathanael’s father, Coppelius carried out secretive, nocturnal experiments, perhaps they tried, by alchemical means, to produce a homunculus, little man.

In any case, Nathanael connected Coppelius's nocturnal visits with the horror stories that adults like to scare children with. Namely, how The Sandman entered the room of disobedient children who did not want to sleep at night and sprinkled sand into their eyes. The children would then rub their stinging eyes so they fell out and the old monster could pick them up, put them in his sack and take them with him up to the “horn of the moon”, where his young ones had their nest and with their owl beaks could gobble up the children's eyes.

According to Nathanael, he hid one night in his father's laboratory and when his hiding place was discovered, he was seized by a furious Coppelius who shouted to his father that his son's eyes were just what they needed to complete their experiments. The father, however, saved his son, but later died in an explosion in his laboratory, which Coppelius escaped.

After the Italian lens salesman Coppola appeared in the German city where Nathanael was studying he soon began to collaborate with Nathanel’s professor, Spalanzani. This made Nathanael's childhood memories of the demonic Coppelius to surface and painful delusions took hold of Nathanael, who to appease his suspicions bought a pair of binoculars from Coppola, whose connection to Coppelius he both believed and denied.

Through his window, Nathanael did often with the help of his binoculars, observe Spalanzani’s beautiful daughter, Olympia, who lived in a house opposite his. Over time Nathanael became increasingly captivated by Olympia's beauty and began to spin enamoured fantasies around her.

During a ball, the chilly Olympia fulfilled Nathanael’s dreams of the perfect womam - she was unearthly beautiful, docile, had a pair of captivating eyes and listened speechlessly to all his romantically overheated meanderings. Even if everyone around testified to Nathanael that Olympia was a soulless, completely indifferent individual, he nevertheless began to neglect his beautiful, lively and clear-minded Clara for the sake of this languid, strange creature.

When Olympia, during a quarrel between Professor Spalanzi and Coppola, is grotesquely revealed to be an extremely sophisticated automaton, and a bloody Spalanzi ends up lying wounded on the floor he hurls Ofelia’s broken glass eyes at Nathanael. His mind snaps and he ends up locked up in a mental hospital. However, he seems to recover and is reunited with Clara, but when he looks at her through the binoculars he bought from Coppola Nathanael is once again seized with madness and tries to murder his fiancé.

This intricate and suggestive story has been interpreted by psychoanalysts such as Freud and has given rise to a number of artistic versions. The best known is probably the first act of Offenbach's opera The Tales of Hoffmann, which is based on The Sandman. Olympia's famous coloratura aria might be enjoyed in the masterful interpretation of the young Korean soprano Kathleen Kim.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9emRjIMZsVk

Léo Delibes's ballet Coppélia from 1870 is also available online, with Mario Petita's classic choreography which places the action in a fantasy Slavic village. In the demanding lead role of Swanilda/Olympia, Natalia Osipova performs one solo dance after another with bravura. If you want to enjoy her performance as the mechanical doll, you might fast forward 52 minutes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-SdkwwJDKNw

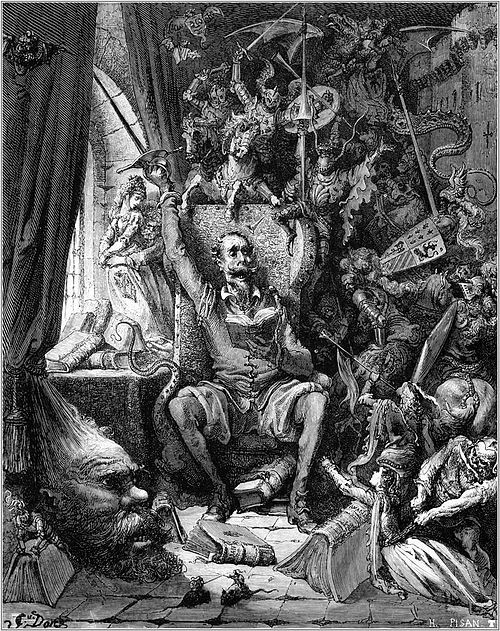

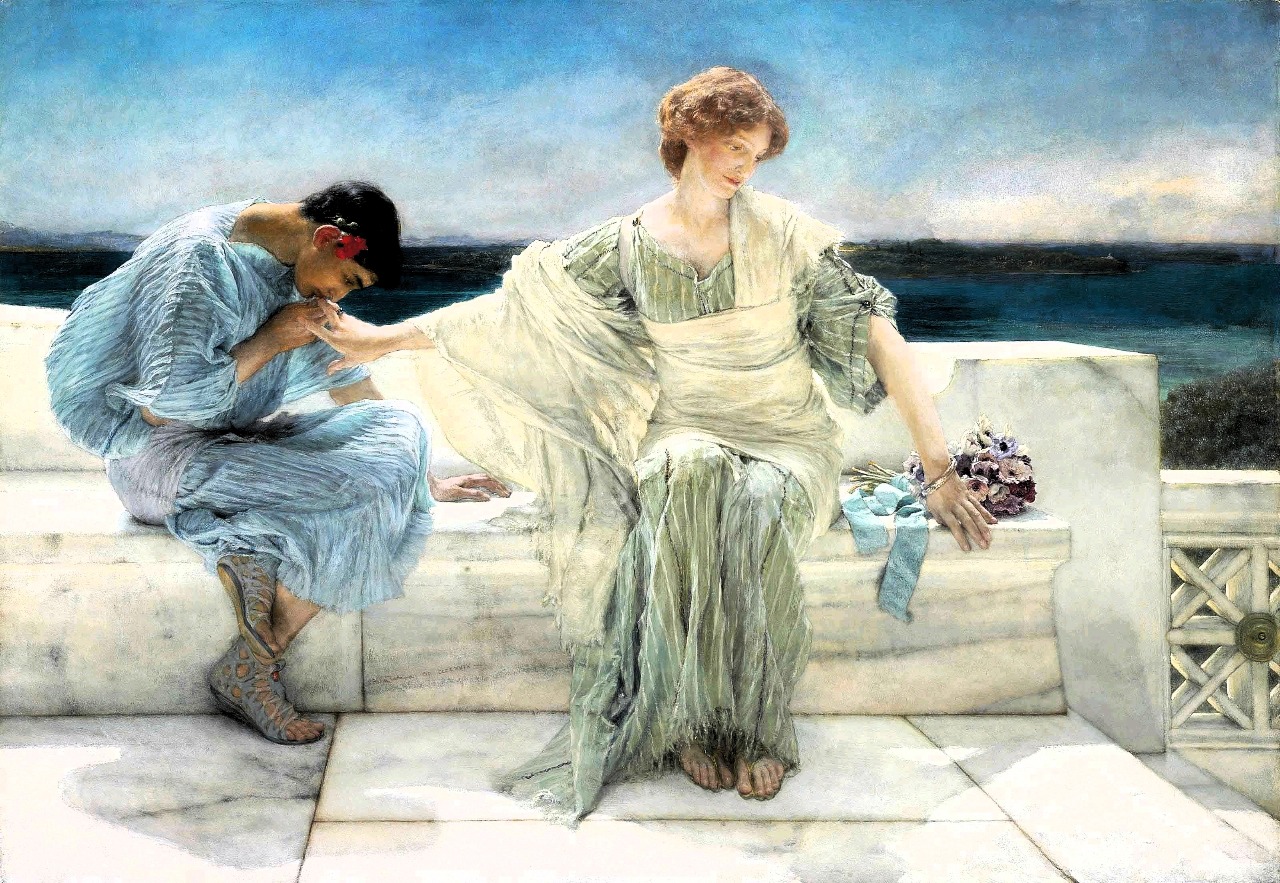

The distorted view of love that an automaton gave rise to in Nathanael probably found its origin in his narcissism, a belief that he was more gifted than others. A distorted view of existence in which even desire and the view of women become abstracted, mechanized, as in the incurably pathetic and fundamentally lonely Don Juan, who lists his every “conquest” as part of a self-glorifying competition with himself and other men. A distorted search that leads nowhere and turns love into an eternal sequence of soulless intercourse has been depicted with sumptuous aesthetics by Fellini in his Casanova. In a key scene, the cold and lonely protagonist dances with an automaton whom he treats as if she was a real and desired woman.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EotNv1Tsa_Q

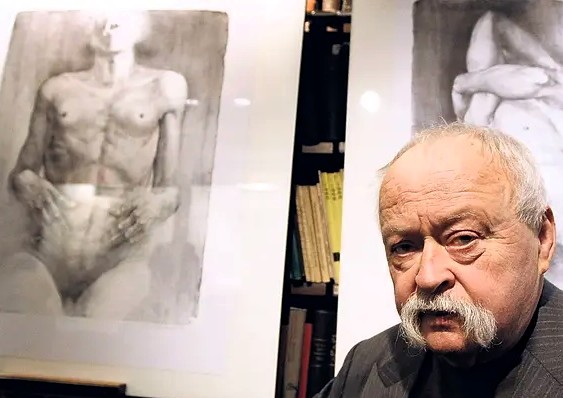

Ever since I bought Göran Printz-Påhlson's poetry collection Gradiva from 1966 at an extra price at a Supermarket sometime in the early seventies, I have been fascinated by automatons. The reason I bought the book was because my father once said that Printz-Påhlson, like me, had been born in the small town of Hässleholm.

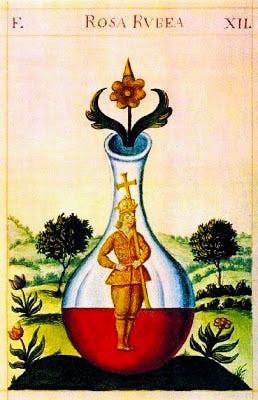

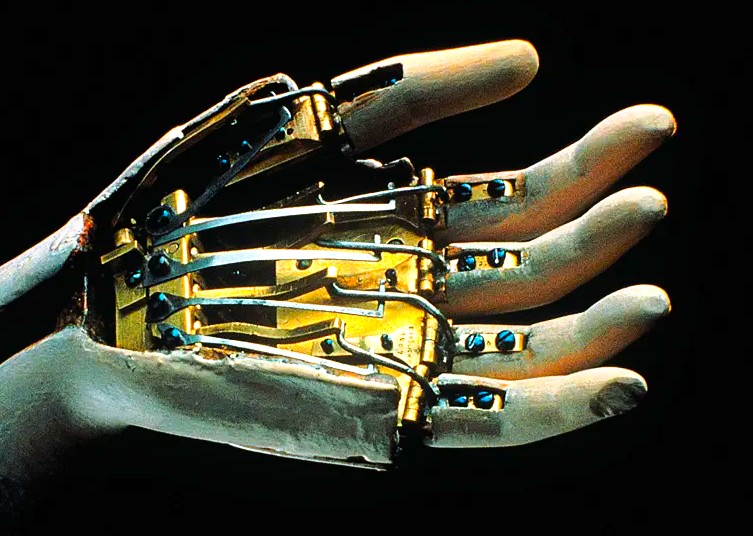

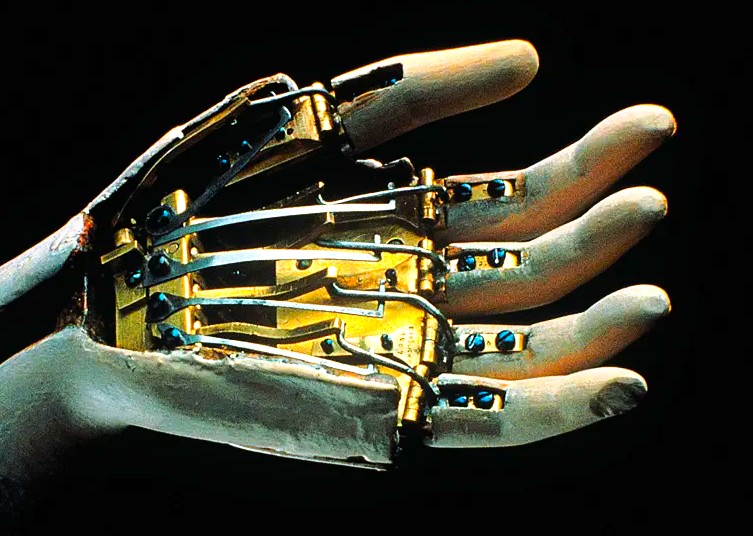

The poetry collection consisted of four different suites that ranged from fantasies about ancient Roman myths to Freud's psychoanalysis, Pop Art and Superman. The third suite consisted of six poems collected under the heading The Automata. A title also alluded to by the book cover, which was said to depict a human hand in cross-section, or in the form of an X-ray, but instead of a skeleton it turned out to cover machine parts. The image apparently depicted a piano-playing automaton hand belonging to a beautiful doll, made by the Swiss Henri Louis Jaquet-Drotz and to general amazement exhibited in London in 1783. An event alluded to by the first poem of the suite.

Most fascinating, considering the present development of AI, is probably the poem that Printz-Påhlson called The Turing Machine.

It’s their humility we can never imitate,

obsequious servants of more durable material:

unassuming

they live in complex relays of electric circuits.

Rapidity, docility is their advantage.

You may ask: “What is 2 times 2?” or “Are you a machine?”

They answer or

refuse to answer, all according to demand.

It is, however, true that other kinds of machines exist,

more abstract automata, stolidly intrepid and

inaccessible,

eating their tape in mathematical formulae.

They imitate within the language. In infinite

paragraph loops, further and further back in their retreat

towards more subtle

algorithms, in pursuit of more recursive functions.

They appear consistent and yet auto-descriptive.

As when a man, pressing a hand-mirror straight to his nose,

facing the mirror,

sees in due succession the same picture repeated

in a sad, shrinking, darkening corridor of glass.

That’s a Gödel-theorem fully as good as any.

Looking at infinity,

but never getting to see his own face.

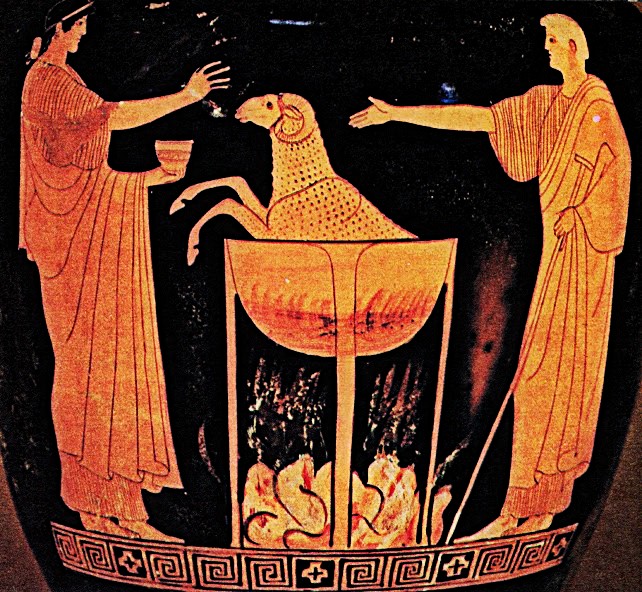

My interest in eighteenth-century automatons made me, while I was living in Paris, to visit Musée des Arts et Métiers, which in its possession has several well-preserved automatons. The most famous is a tympanum-playing doll called Petit Dauphine, which when screwed up strikes the instrument's strings with small hammers, playing eight melodies, including the Shepherdes’s Aria from the opera Armide by Christoph Willibald Gluck, Marie-Antoinette’s favorite composer. The automaton was probably built in 1784 and delivered to the French court the following year. The manufacturer was not Jaquet-Drotz, but the German cabinet-maker David Röntgen, who since 1772, in collaboration with the watchmaker Pierre Kintzing, had been making several automatons.

Marie-Antoinette was delighted with Petit Dauphine and later donated her to the French Academy of Sciences, where she in 1864 was restored by the famous magician Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin (1805-1871), not to be confused with the even more famous Harry Houdini.

The latter was originally Hungarian and his actual name was Ehrich Weisz. He came to the United States at the age of four and when Weisz had become a world-famous magician and king of escape artists, he took the stage name Harry Houdini to pay tribute to the two magicians he admired most of all – the American Harry Keller and Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin.

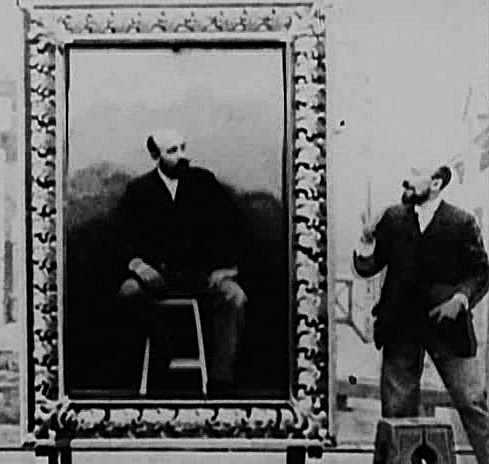

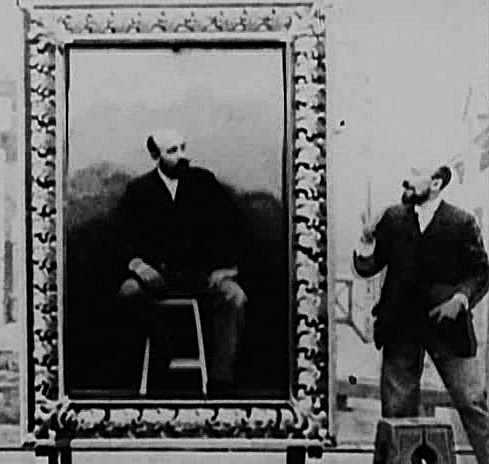

In 1888, the successful magician Georges Méliès bought the Théâtre Robert-Houdin from the great magician's widow. The purchase included all of the theatre's equipment, including a large number of automatons, which Méliès improved and used in his performances.

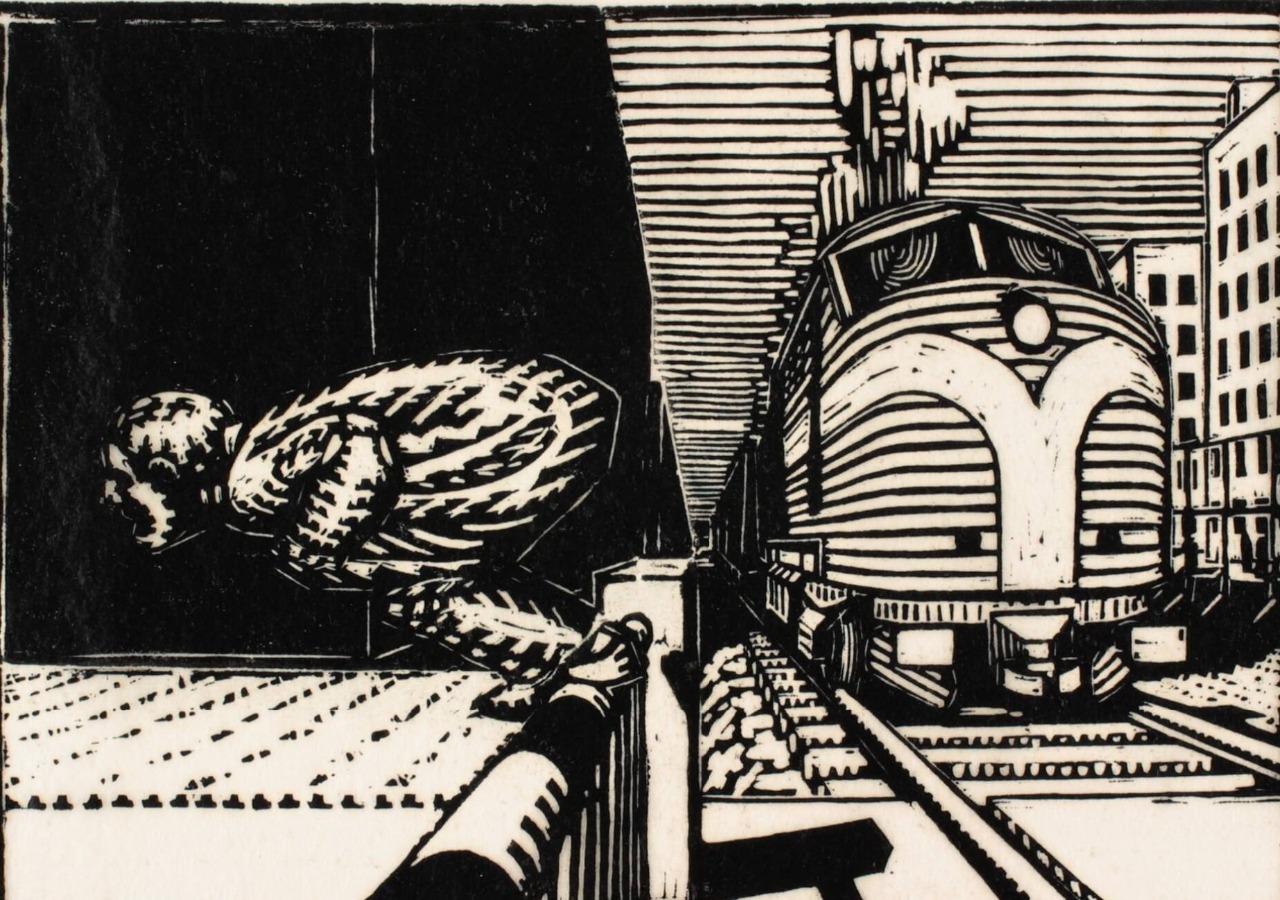

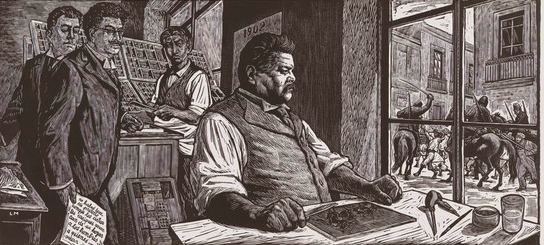

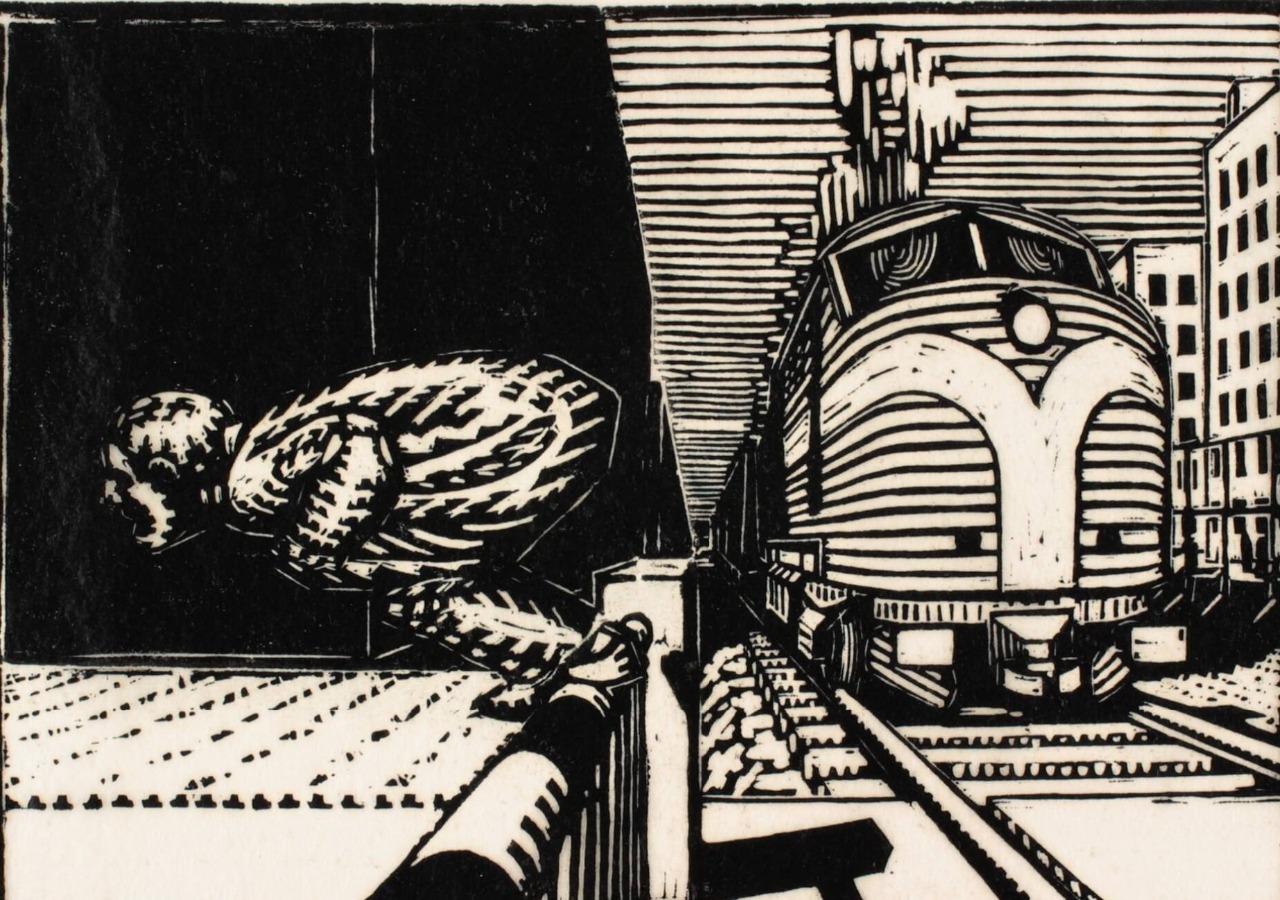

In 1896, Méliès began to create “trick films” (as early as 1897, he made the short film Gugusse and the Automaton, the first film to feature a mechanical android, which furthermore also seemed to have a mind of its own). Méliès presented the films at his theatre and by 1913 he had produced no less than 500 imaginative and revolutionary films, each of them lasting between one and forty minutes. His success and increased competition made Méliès increasingly bold, and excessive investments caused his company to collapse in 1913. In the same year, his first wife died. Méliès was forced to close the Théâtre Robert-Houdin and left Paris for a long time, together with his two young sons.

Méliès was largely forgotten and financially ruined when he in 1925 married the actress Jeanne d'Alcy, who had appeared in several of his films,. The couple supported themselves by running a small candy and toy stall in the main hall of the huge train station Gare Montparnasse.

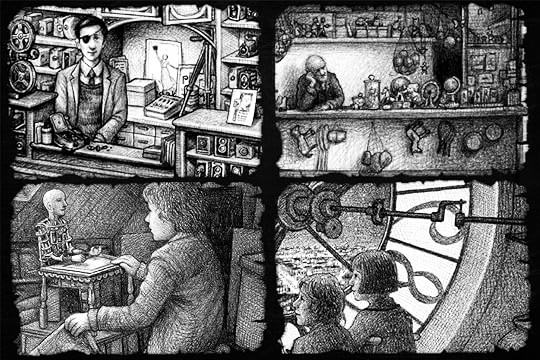

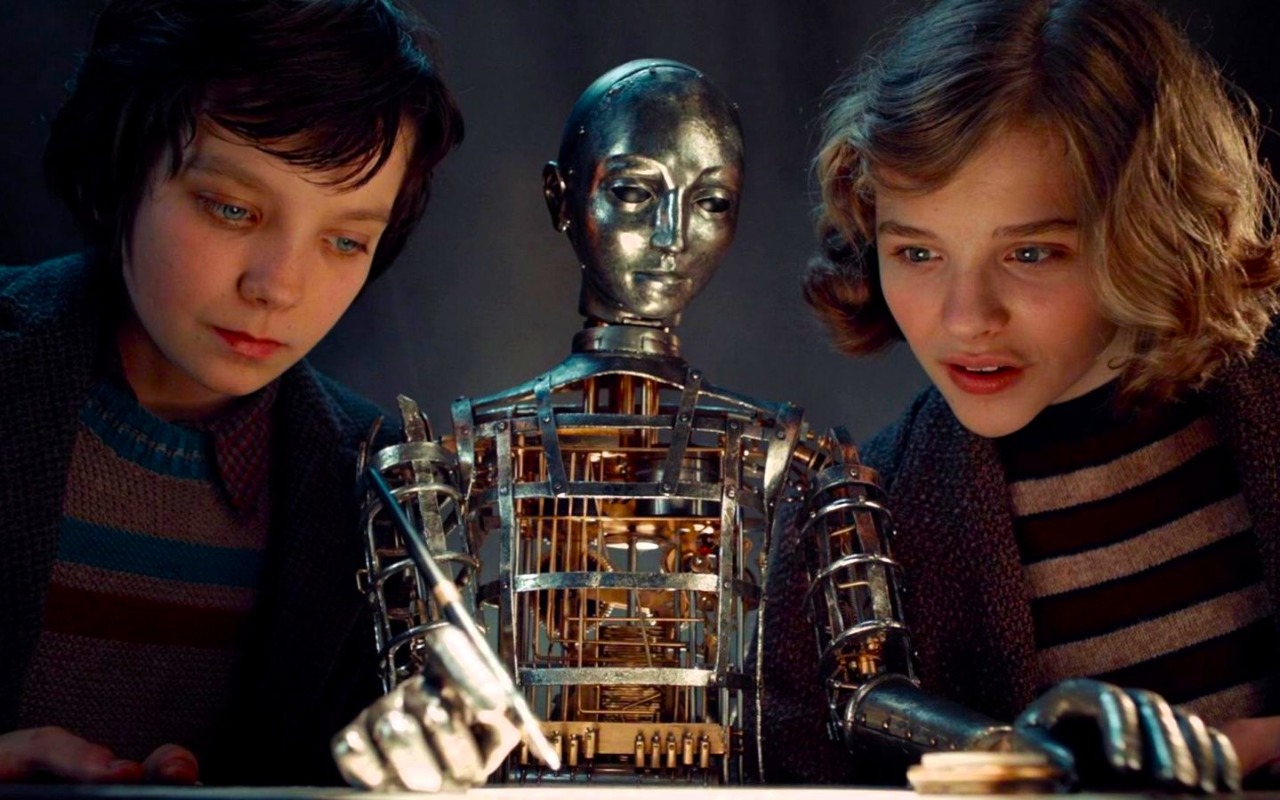

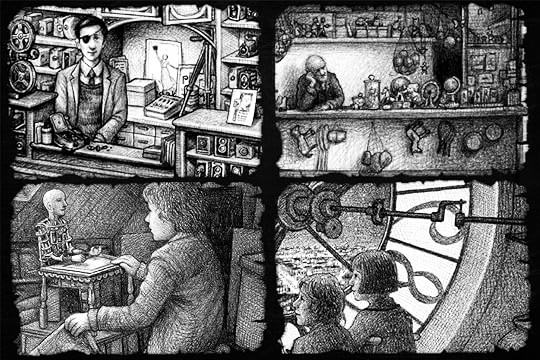

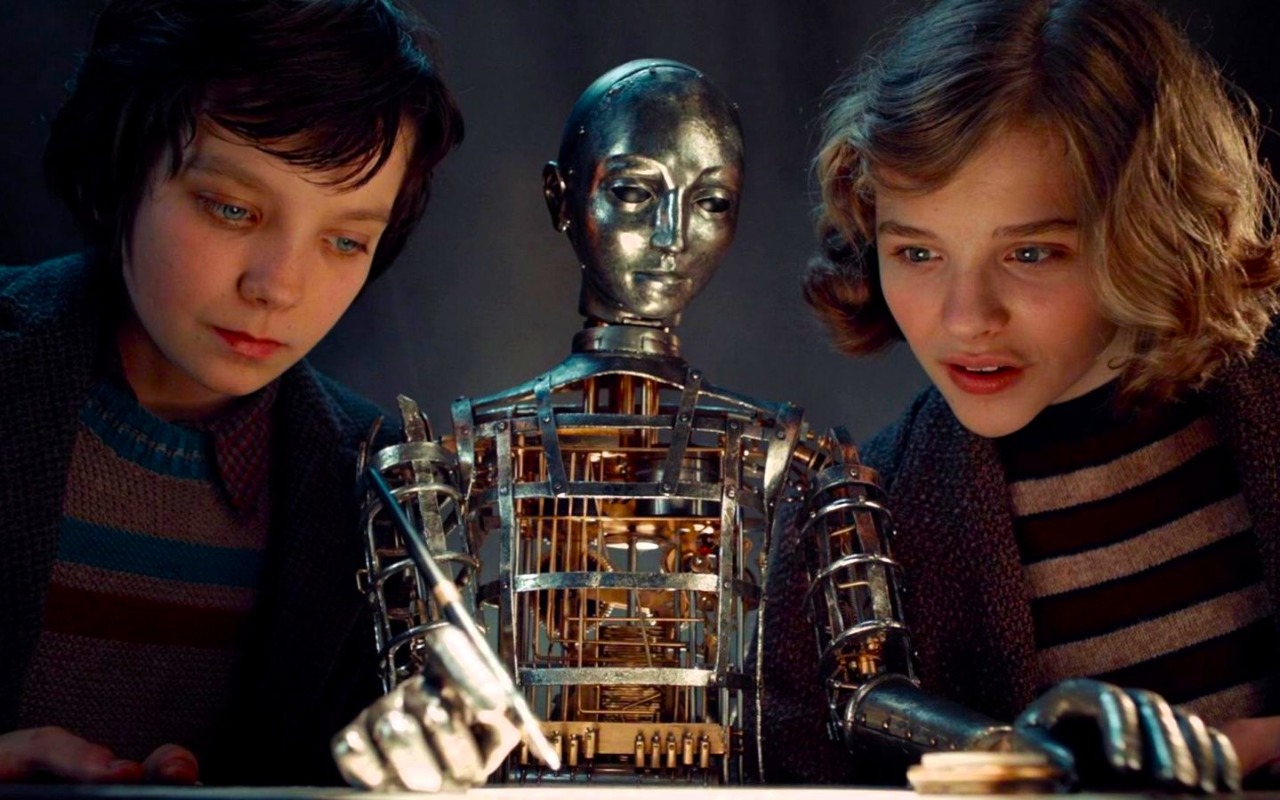

An automaton designed by Méliès plays an important role in Brian Selznik’s 2007 picture book The Invention of Hugo Cabret. The graphic novel is set in Paris in the early thirties when the young Hugo Cabret and his father are repairing an automaton they found in the attic of the museum where the father works (Méliès had actually donated his automatons to a museum, where they had been destroyed by rain and rust).

When Hugo’s father dies in a fire, his alcoholic uncle takes the orphaned boy with him to live and work at the Gare Montparnasse, where he maintains the clocks. When his uncle dies, Hugo stays behind in the station, where he hides and takes up his uncle's work, worried about being sent to an orphanage. He has the automaton with him and eventually confronts Méliès and begins to work in his toy stall.

Shortly after I had seen the automatons at the Musée des Arts et Métiers, Martin Scorsese's film adaptation of The Invention of Hugo Cabret premiered in Paris. It was a fairly faithful interpretation of Selznick's novel, based on reality and clearly inspired by his drawings, but Scorsese’s film was much more than that.

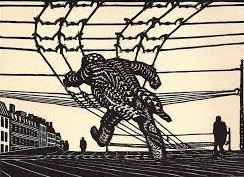

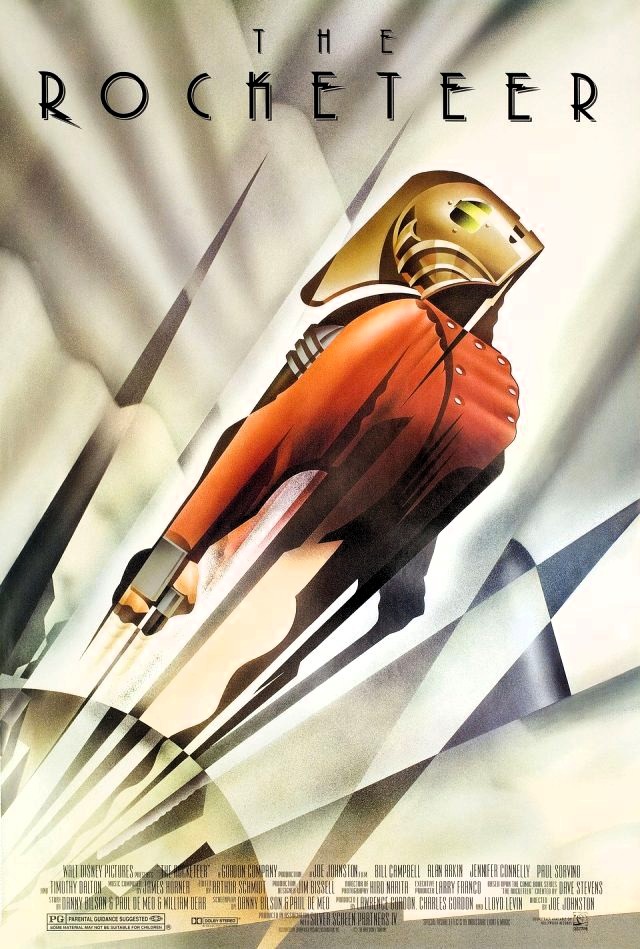

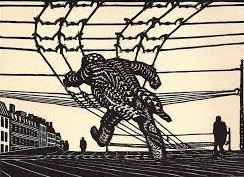

Hugo Cabret is the only successful three-dimensional film I have seen, and that was entirely appropriate because it is a tribute to the art of cinema; its origins, craftsmanship, imagination and enchantment. Hugo Cabret's existence and work among the intricate and heavy mechanics of the great clockworks, the steam locomotives and the mysterious automaton have a close resemblance to the film genre that has come to be called steampunk, i.e. a subgenre within science fiction that is characterized by a retro-futuristic technology and aesthetics inspired by the industrial steam-powered machines and design of the 19th century.

At the same time, the cinematically well-educated Scorsese has managed to present a true-to-life picture of Méliès’s world and how his fantastic films were created. Scorsese’s Hugo Cabret is furthermore an exciting and heartwarming film, which effect on me was not dampened by my often nostalgically lonely Parisian existence.

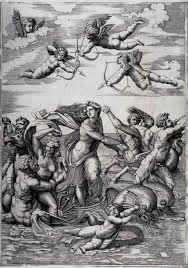

.png)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Tj1KAlzCNg

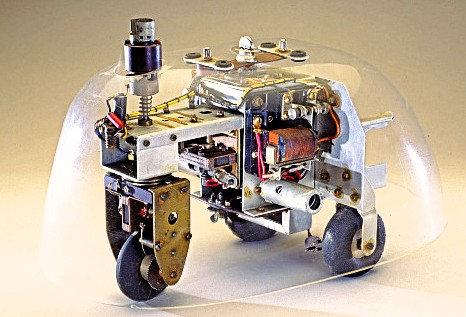

Most of today's robots are not any android automatons but industrial robots, which currently number around 4.5 million and are constantly working around the world.

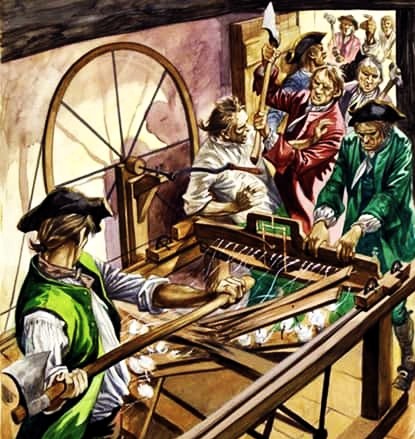

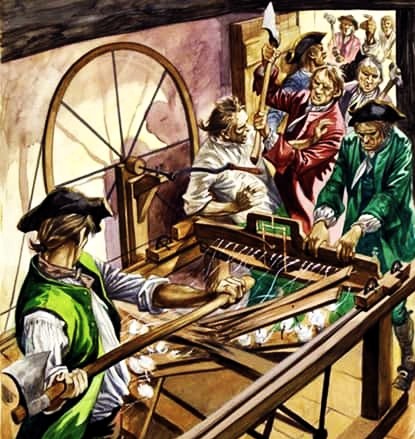

Machines that do not require, or at least limit, human labour are nothing new. Especially in the latter part of the eighteenth century, violent riots broke time after time out in England when so-called Luddites destroyed factories and machines. It was especially new cotton spinning techniques that were met with violent resistance. New inventions produced textiles faster and cheaper than had previously been possible by home spinning looms and simple factories, and the recently invented machines could be handled by less skilled, low-paid workers.

However, those primitive machines were nothing compared to today's sophisticated industrial robots, which are characterized as such after being approved by and adapted to so-called International Standards on Robotics, established by The International Organization for Standardization (ISO), standards including “safety, performance criteria, modularity and vocabulary.”

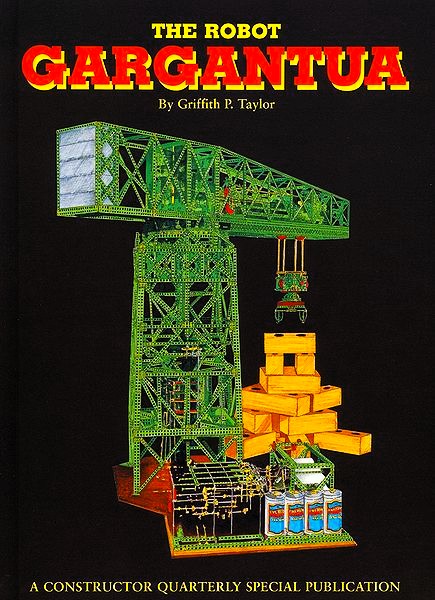

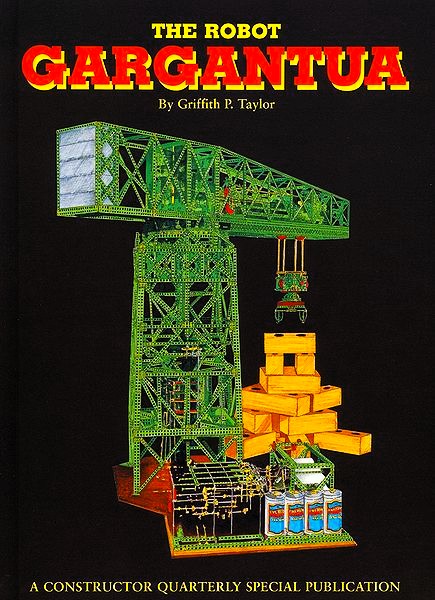

The earliest known industrial robot that met ISO’s standards and definitions was created in 1937 by “Bill” Griffith P. Taylor. This crane-like device was built almost entirely with Meccano parts and was powered by an electric motor. Five axes of motion allowed for sophisticated gripping and rotation. Automation was achieved using perforated paper tape that activated electromagnets.

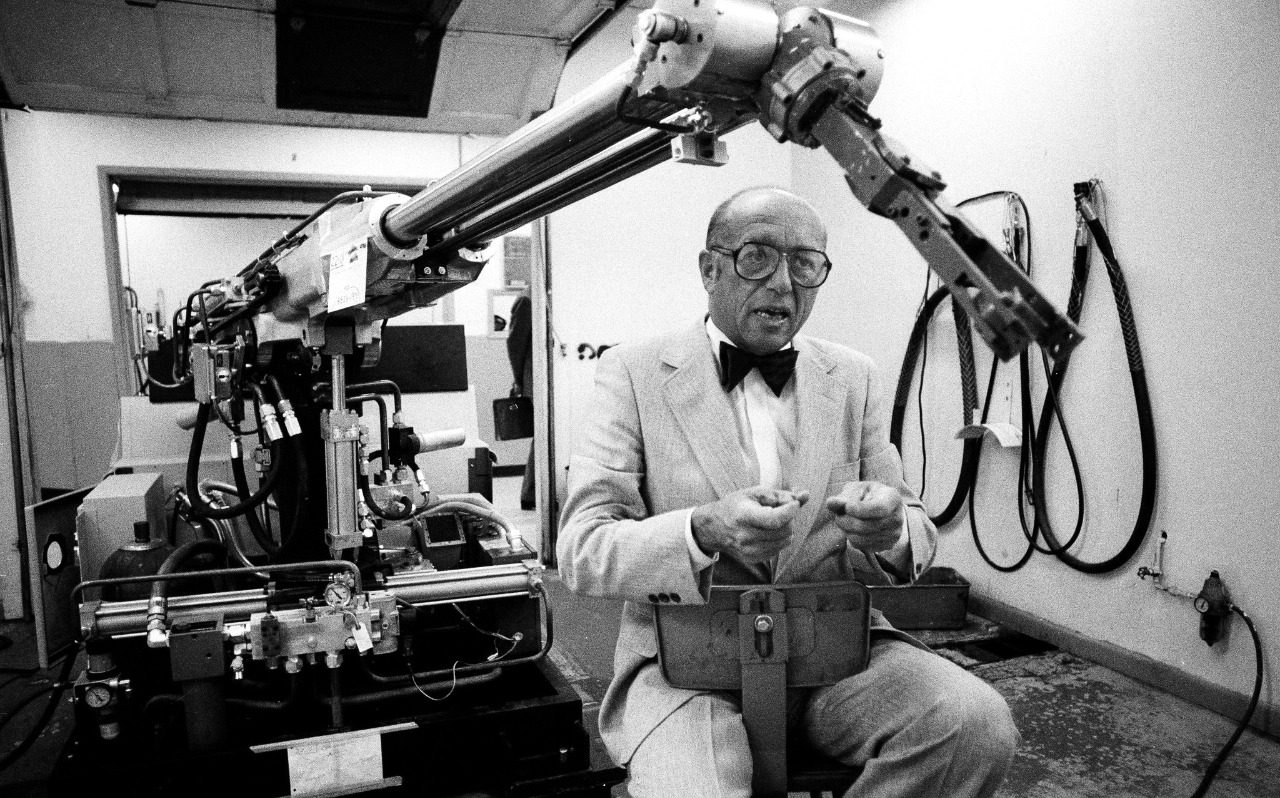

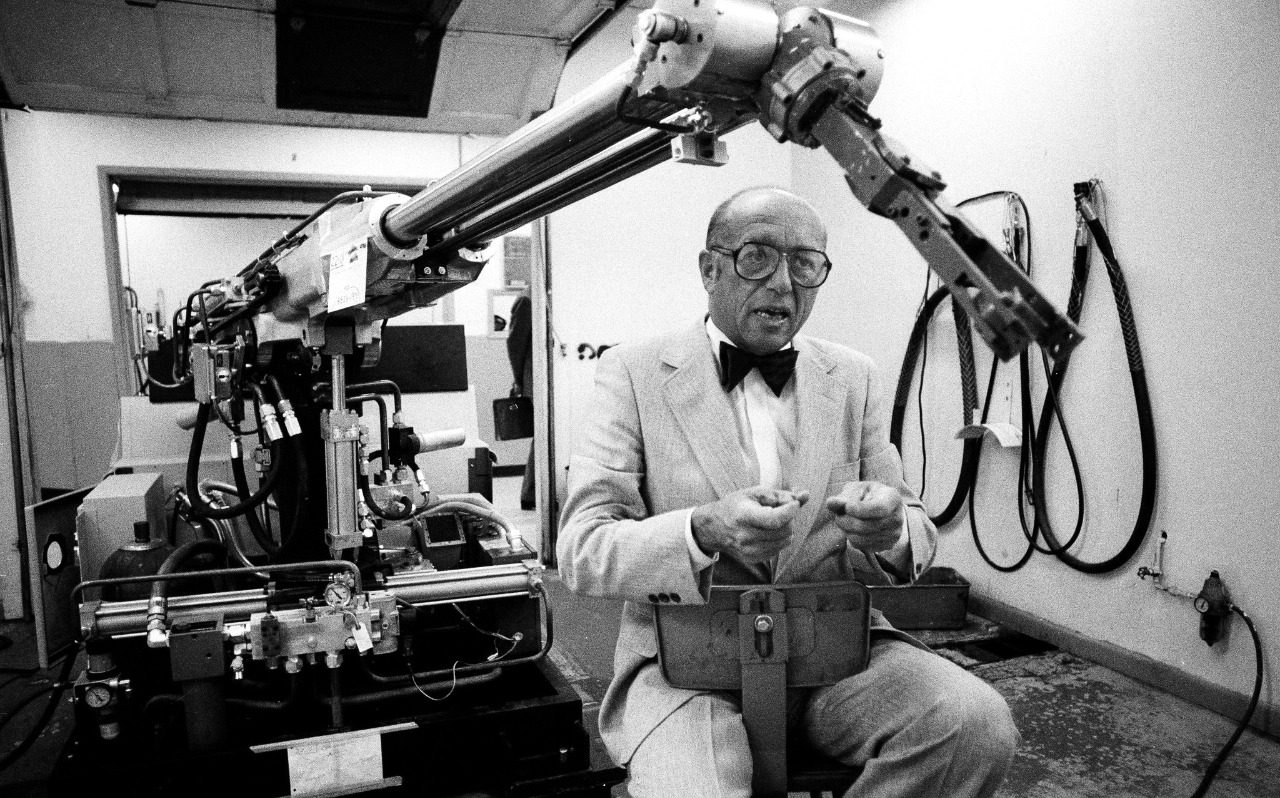

However, it was not until 1961 that the company Unimation was able to manufacture and market a reasonably efficient industrial robot, but industrial robotics did not really take off until 1977 when both ABB Robotics (formerly ASEA) and KUKA Robotics launched their commercially available, fully electrified microprocessor-controlled robots.

The first “autonomous” robots, i.e. machines that act without human control, were called Elmer and Elsie and designed in the late 1940s by W. Grey Walter. They were the first robots programmed to “think” in a way similar to what biological brains do and were intended to have free will.

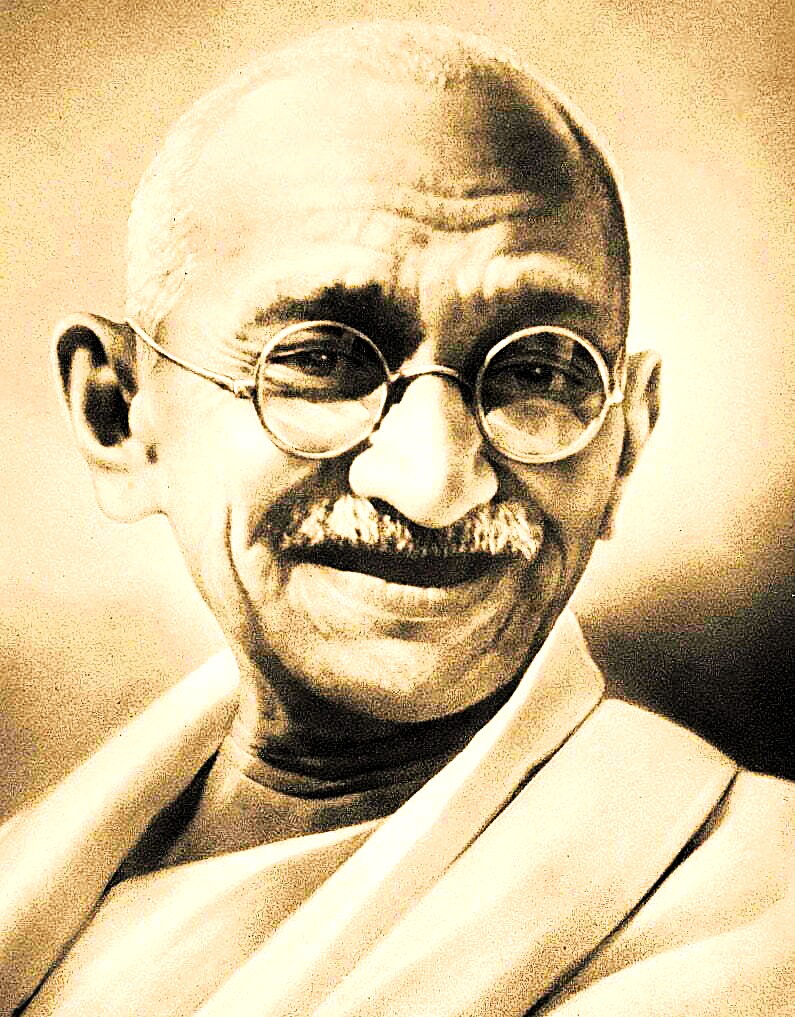

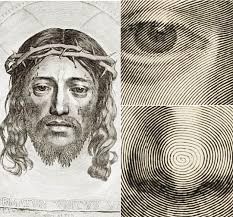

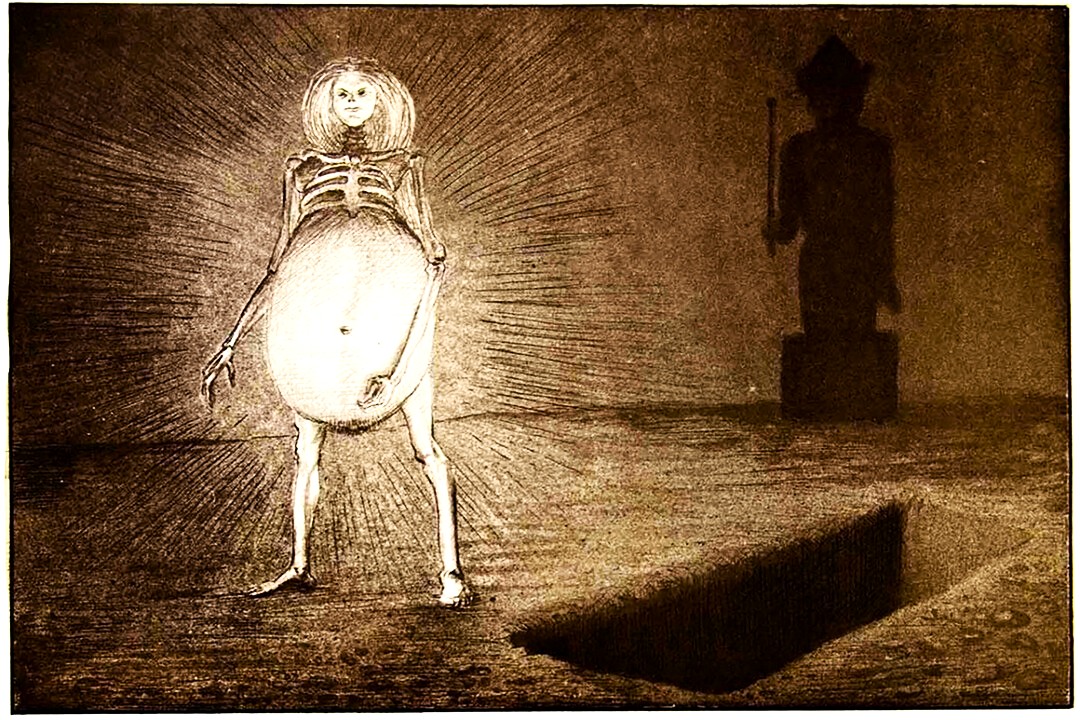

Tegmark's & CO's SF-like cosmic visions of a future in the clutch of A.I., seems to me as if we humans are in the process of creating an omnipotent entity similar to the God that so many of us previously believed in, and many of us still assume is around – Almighty, All-seeing, Righteous and therefore incomprehensible in all His Highness. “Glory to God in the highest heaven”:

For to us a child is born, to us a son is given, and the government will be on his shoulders. And he will be called Wonderful Counsellor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace.

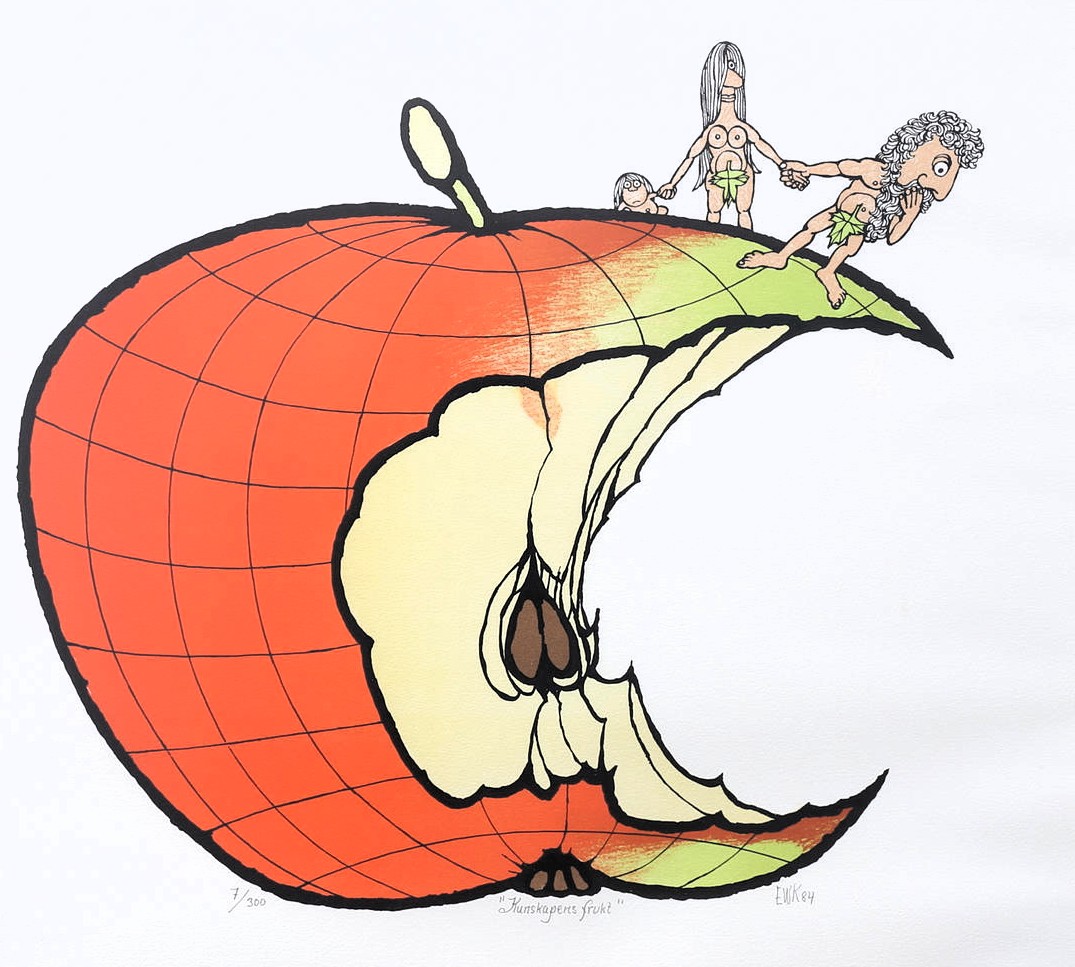

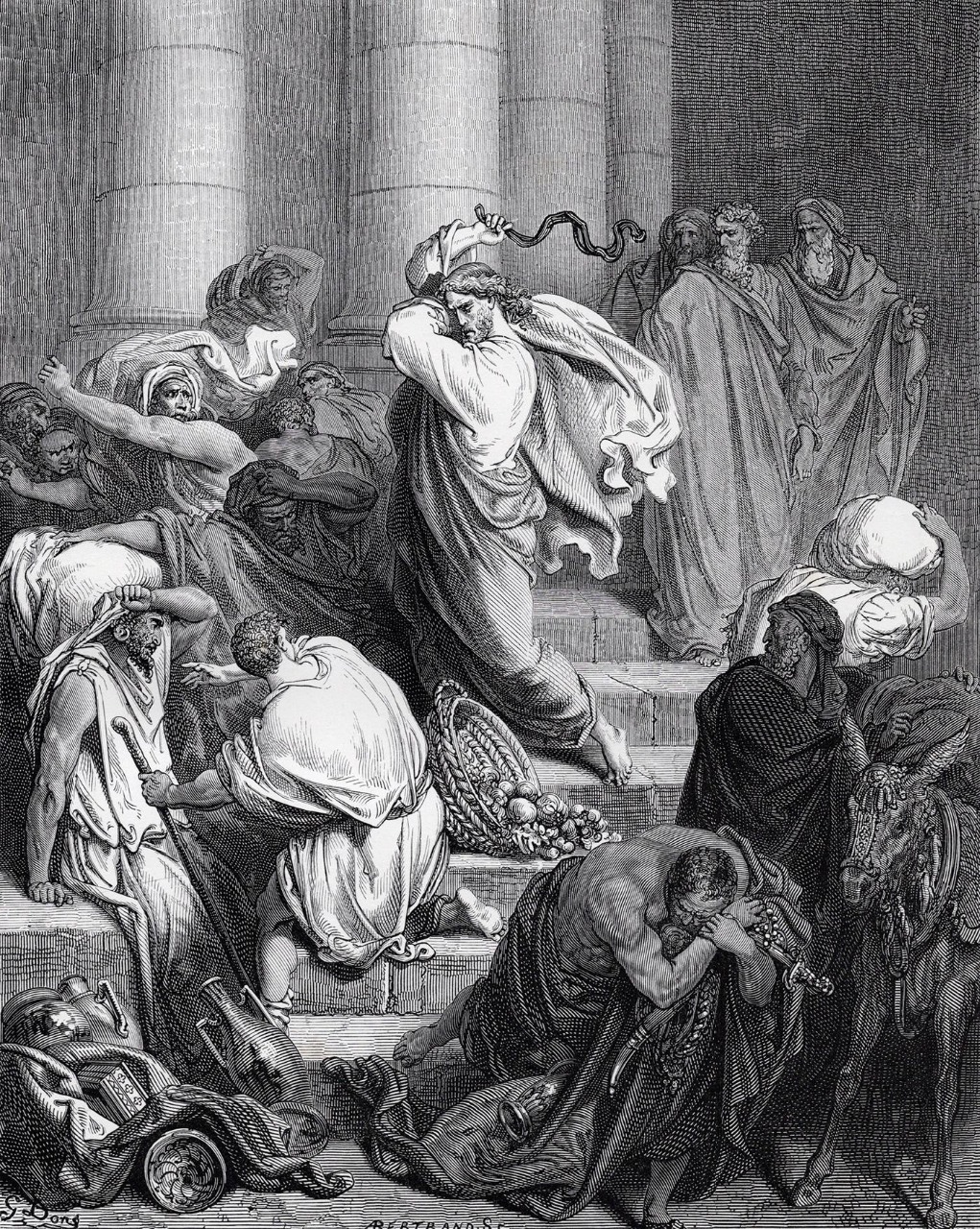

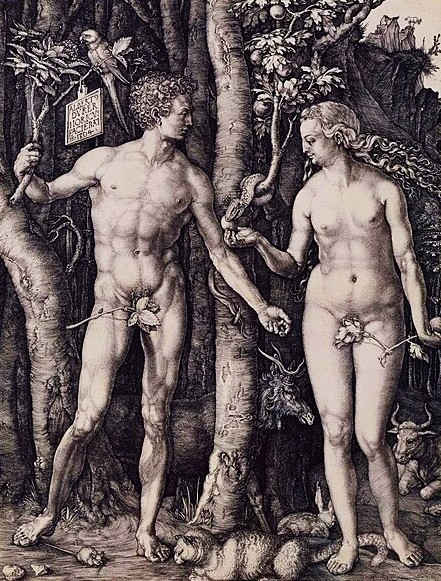

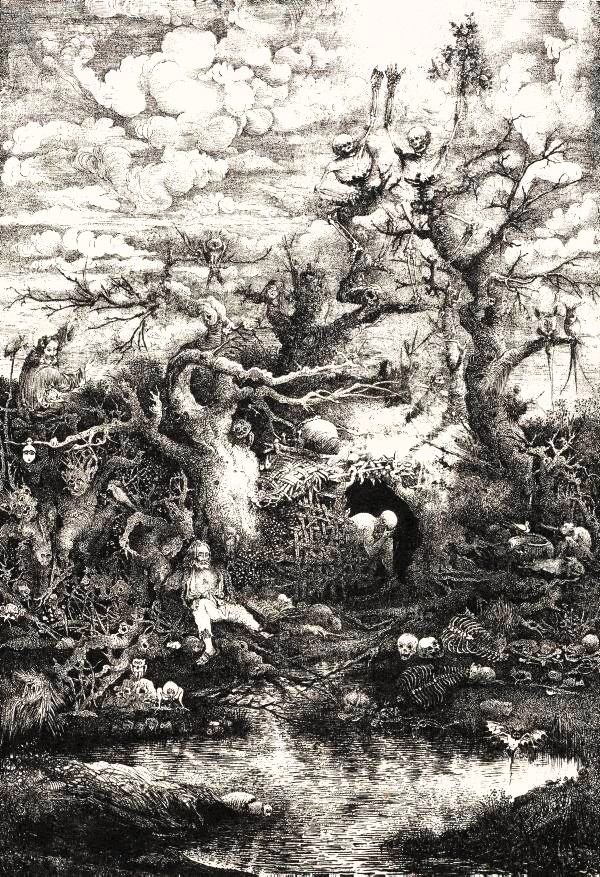

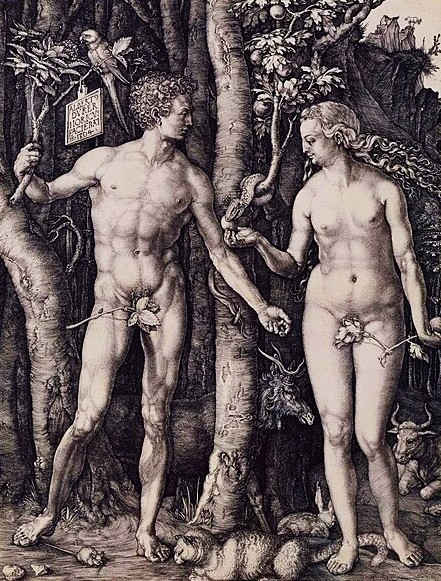

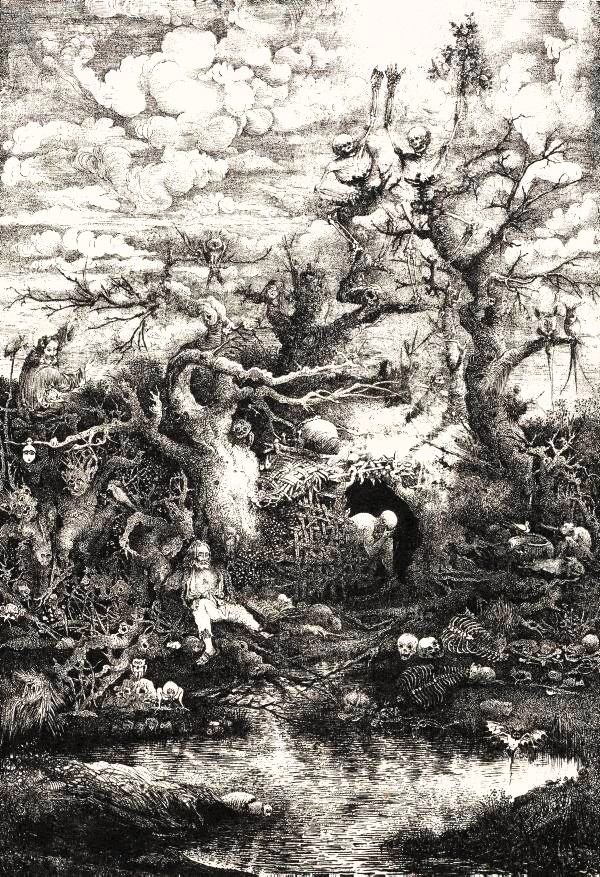

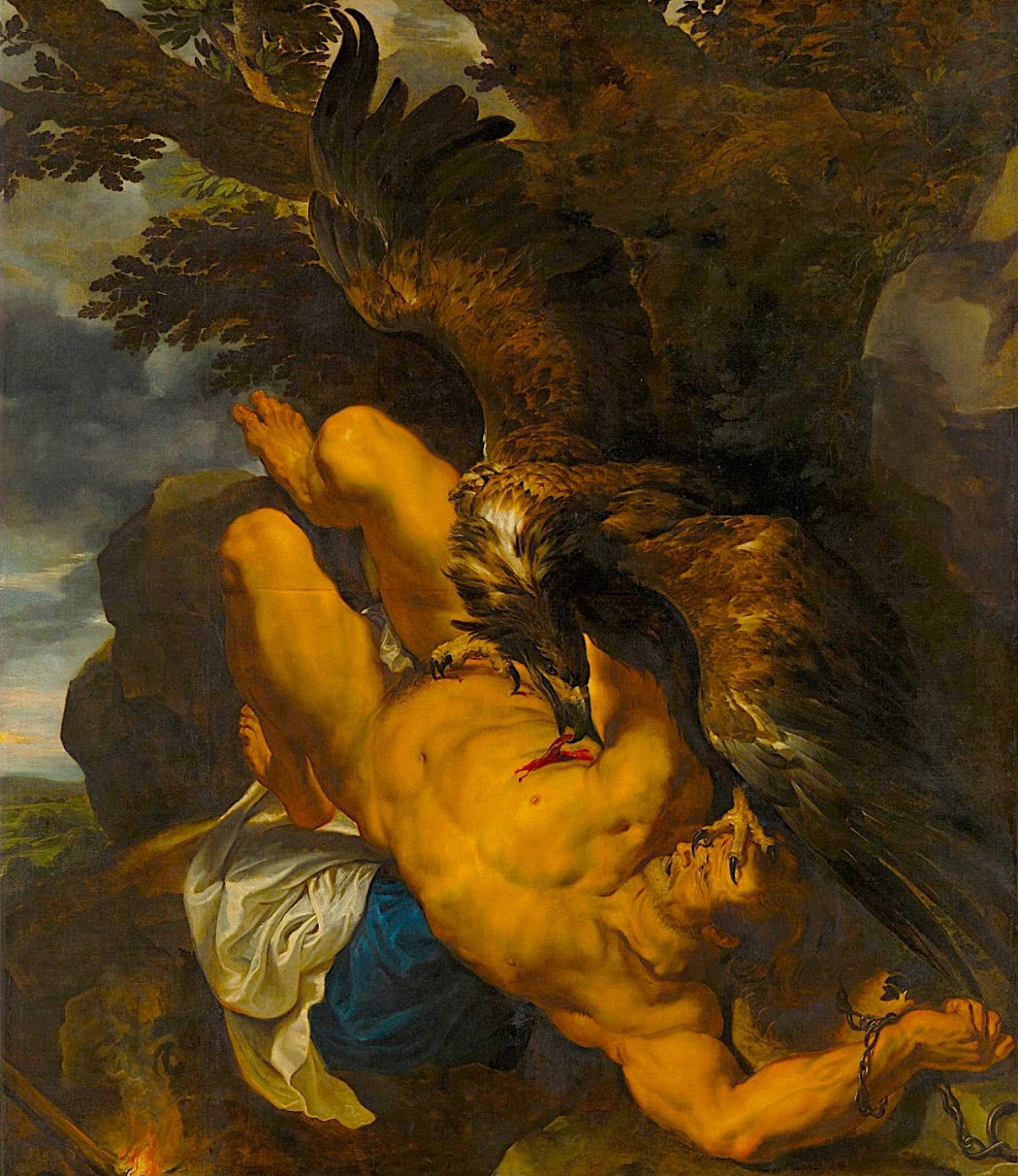

We are no longer masters of Creation. We have handed over that power to our own manufactures – the computers. Accordingly, we have produced a new power, an all-powerful Lord that is far more powerful than we ourselves have ever been, or can ever be. It is as if we have realized the old myth of the Garden of Eden, where at the beginning of Creation we lived in peace, harmony and justice under a perfect and all-ruling Lord, who only wished us well. But we exalted ourselves and believed that with the help of our God-given wisdom we could be like gods ourselves.

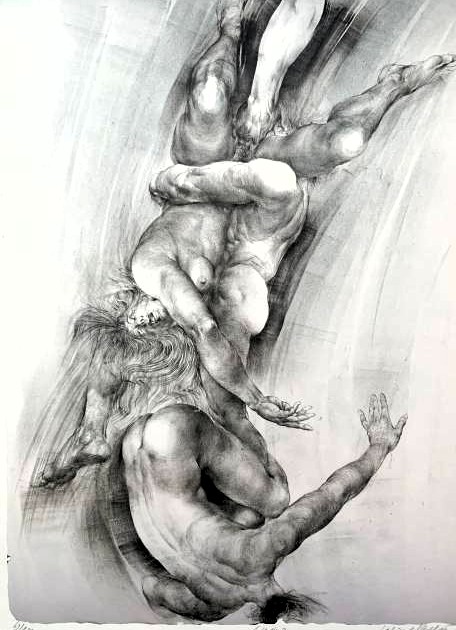

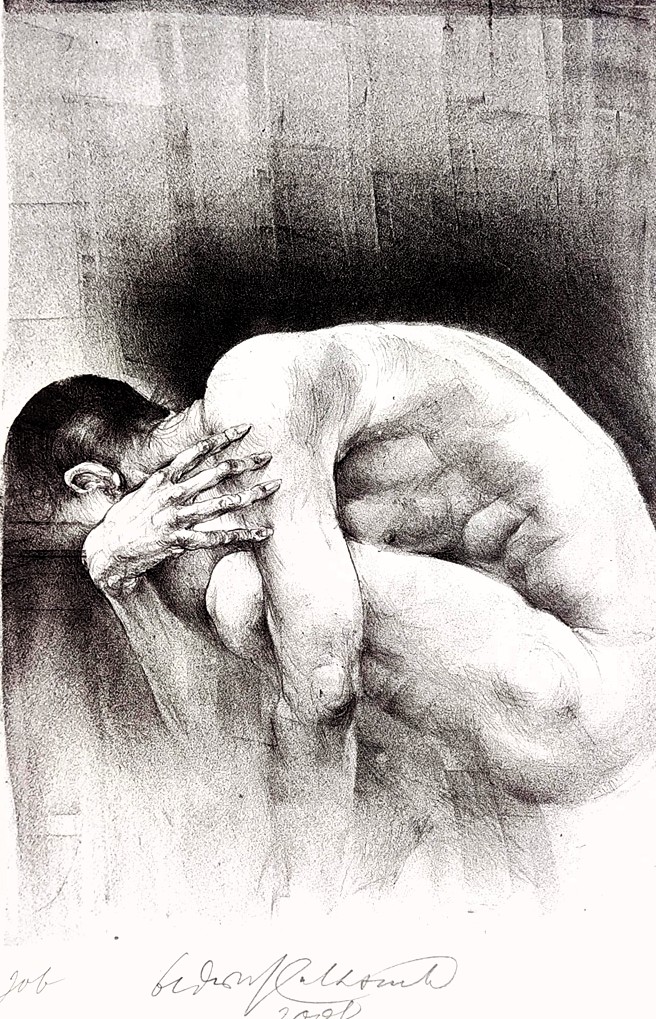

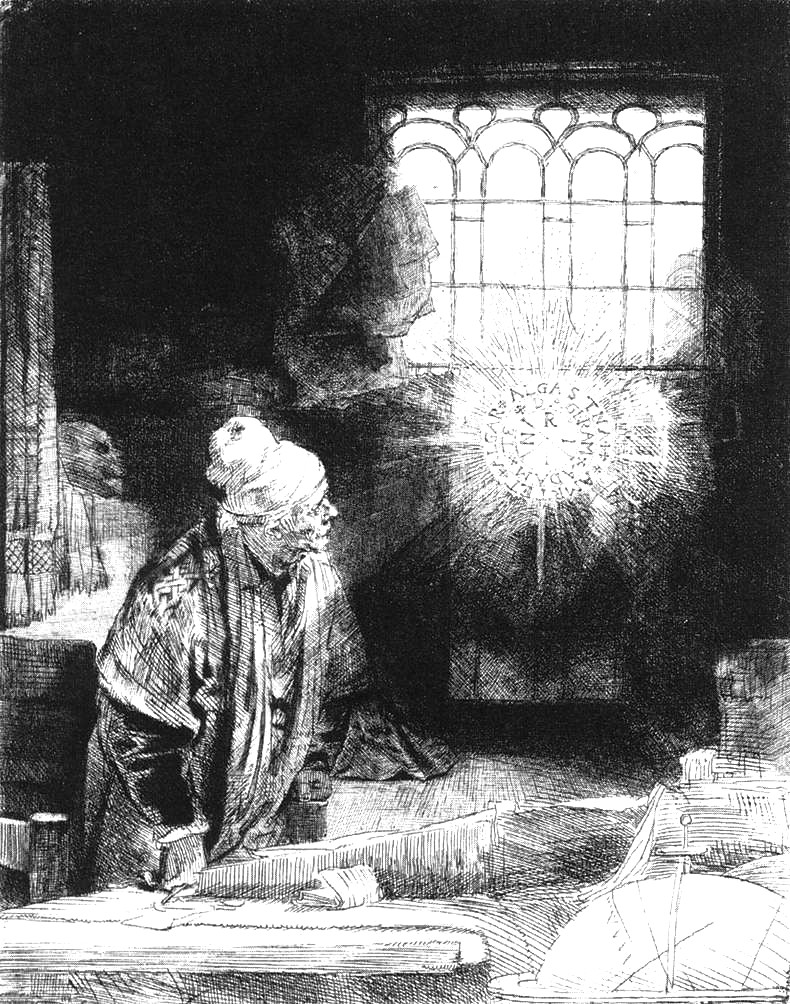

.jpg)

God realized this and, like a righteous father who knew that his children had grown up and could now take care of themselves albeit with great difficulty – he drove us out from his cozy Paradise and let us take care of his Earth.

Then the Lord God said, “Behold, the man has become like one of Us, knowing good and evil; and now, he might stretch out his hand, and take also from the tree of life, and eat, and live forever”— therefore the Lord God sent him out from the garden of Eden, to cultivate the ground from which he was taken.

And what have we done with this intelligence that equated us with the gods? We have created our own Almighty God.

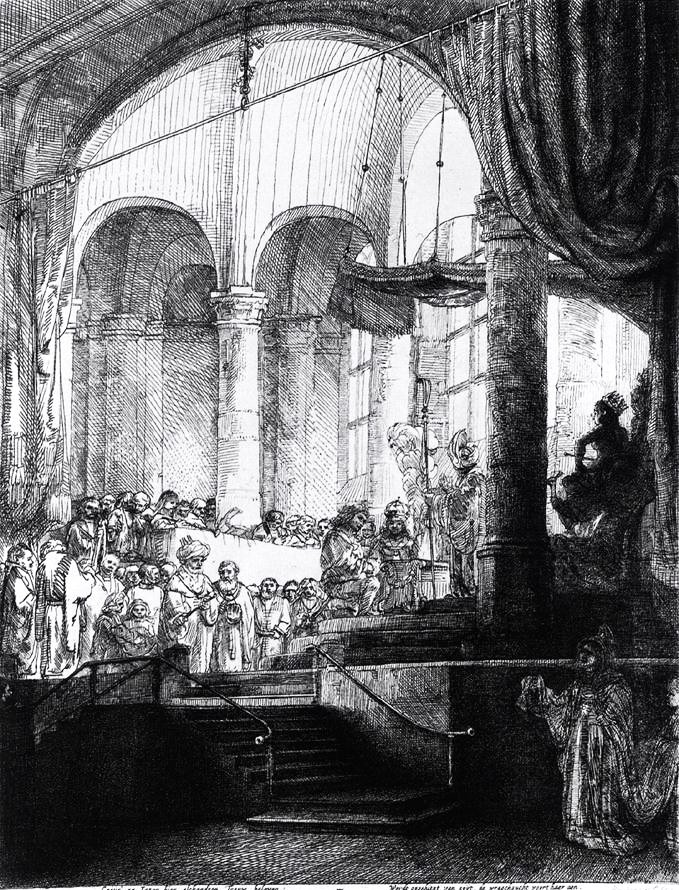

According to the prophets of the Bible, God was resentful of man's efforts to create his own gods, thus ignoring that He was the Almighty, the only God, Our Lord, Creator, and Protector. According to the Prophet Isaiah, God declared:

This is what the Lord says – he who made you, who formed you in the womb, and who will help you: […] Is there any God besides me? No, there is no other Rock; I know not one. […] Who shapes a god and casts an idol, which can profit nothing? People who do that will be put to shame; such craftsmen are only human beings. Let them all come together and take their stand; they will be brought down to terror and shame

Being a solid scientist Tegmark does not address religious teachings. I would suspect that he, like so many of his fellow researchers and technicians (those whom Isaiah calls “the artisans”), believe that God, like the more tangible computers, is created by humans.

The “God” who is now impersonated by the computers, who through self-programming will become superior to us (and even in some areas already has become so), can probably also provide itself with “human” emotions. Through the sovereign intelligence that A.I. now is acquiring it can hopefully realize the danger of, as we humans are now doing, putting its habitat at risk. Therefore, in order to ensure its existence, and perhaps even that of humanity, it may be in the self-interest of Artificial General Intelligence, like a benevolent deity, to take care of medicine, research, and justice in such a way that it promotes a just world characterized by respect for every living being and care for nature. Such an outstanding intelligence can possibly halt climate destruction, promote a perfectly objective justice and everyone’s right to a happy life, in which our human needs are met and natural resources are sustainably and fairly distributed.

As far as possible, however, we humans should, while there is still time, ensure that the superior intelligence we are now in the process of creating is endowed with sufficient empathy and humanitarian feelings to allow us humans to live on.

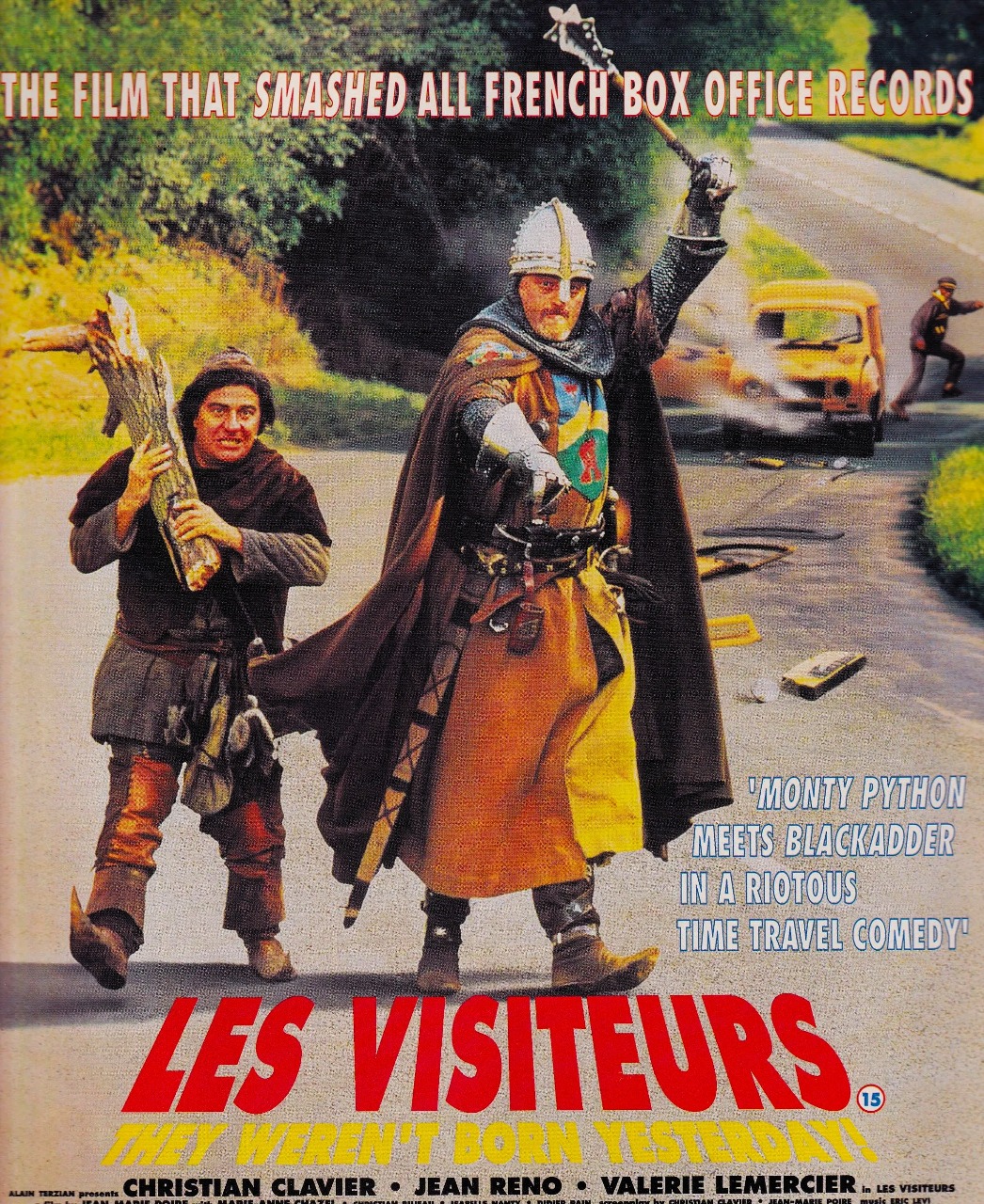

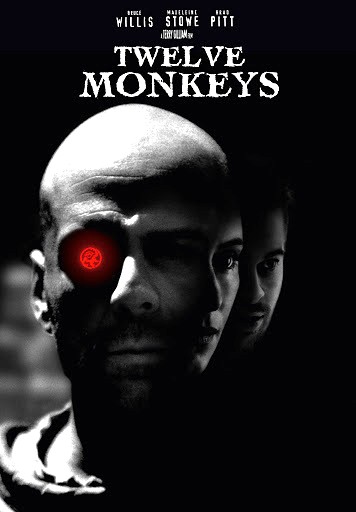

Otherwise, it can be like in the former Wachowski brothers' (they were formerly brothers, but are now transgender persons) skilfully made Matrix trilogy (made between 1999 and 2003, a fourth addition I have not yet seen). In these films, people live in a computer-generated, alternative and fictional “reality”, except for a small group of rebels who are trying to fight the icy logical domination of machines.

Or as the computer-generated Agent Smith puts it:

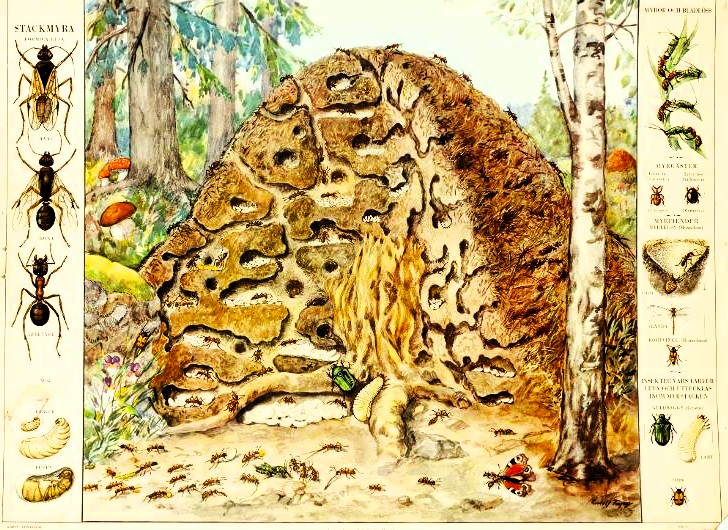

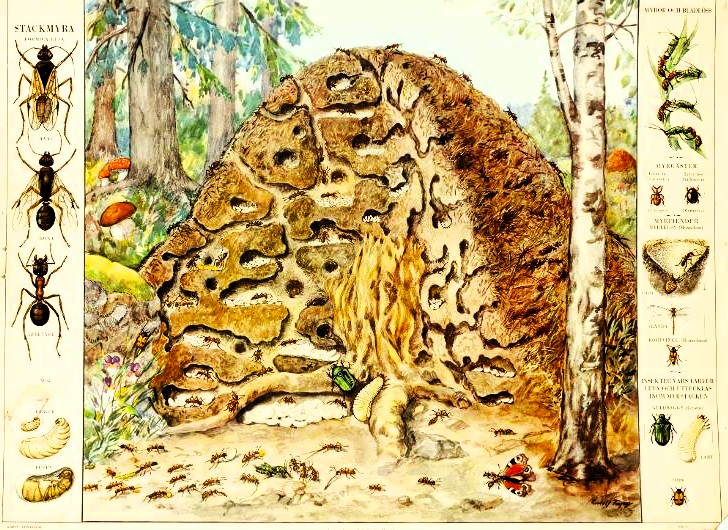

I'd like to share a revelation during my time here. It came to me when I tried to classify your species. I realized that you're not actually mammals. Every mammal on this planet instinctively develops a natural equilibrium with the surrounding environment but you humans do not. You move to an area and you multiply and multiply until every natural resource is consumed. The only way you can survive is to spread to another area. There is another organism on this planet that follows the same pattern. Do you know what it is? A virus. Human beings are a disease, a cancer of this planet. You are a plague, and we are the cure.

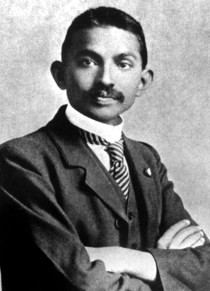

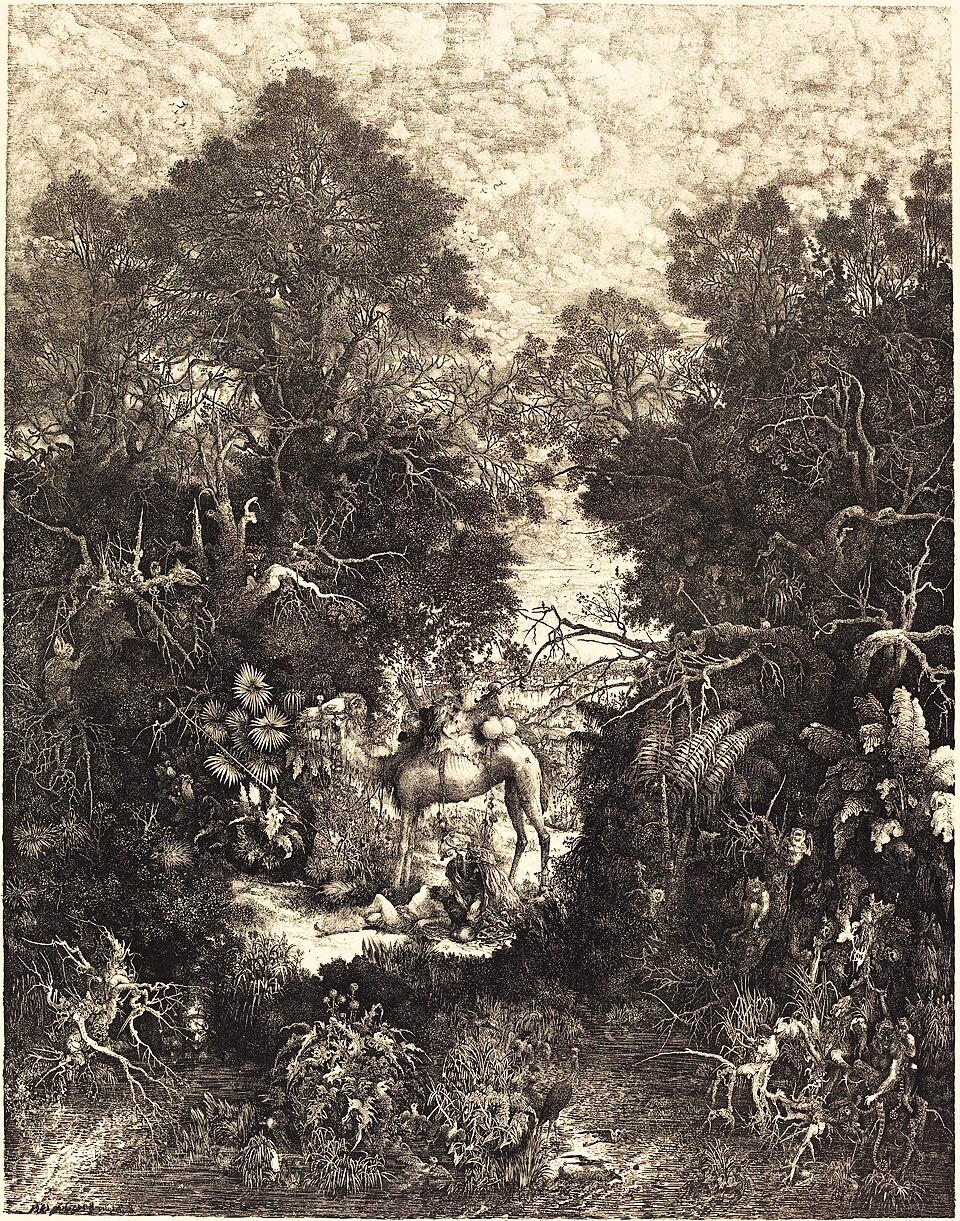

Max Tegmark was far from first to write about the enormous possibilities of A.I. outside the science fiction sphere. The same year as his 3.0 came out, I started reading Yuval Noah Harari's Homo Deus on the train between Durham and Liverpool and was thoroughly shaken by Harari’s vision of an A.I.-controlled future. I took short breaks in my reading and looked out the train window. That’s one reason to why I like to travel by train – to sit by the window and read, immersed in the book’s plot, make a pause to contemplate for a while and then occasionally lift my head and watch the world rush by out there, knowing that every house we pass contains a unique story.

For as long as I can remember, I have been fascinated by train travel; the idea that the places we pass by are home to someone who knows every stone, every tree around them, every street, every shop. I looked out the window and wondered what the landscape I saw would look like in fifty years from now, what the existence of people would be like then.

The most important products of a future economy will not be food, textiles and vehicles, but rather bodies, brains and minds. This will not only mean the greatest revolution in history, but the greatest revolution in biology since life arose on Earth.

It is quite possible that in the near future humanity may have come a long way to achieving happiness, general health, and having at its disposal almost godlike powers. However, Halal warns that A.I. and biomanipulation may be monopolized by limited, privileged and outrageously wealthy groups, living within a few countries.

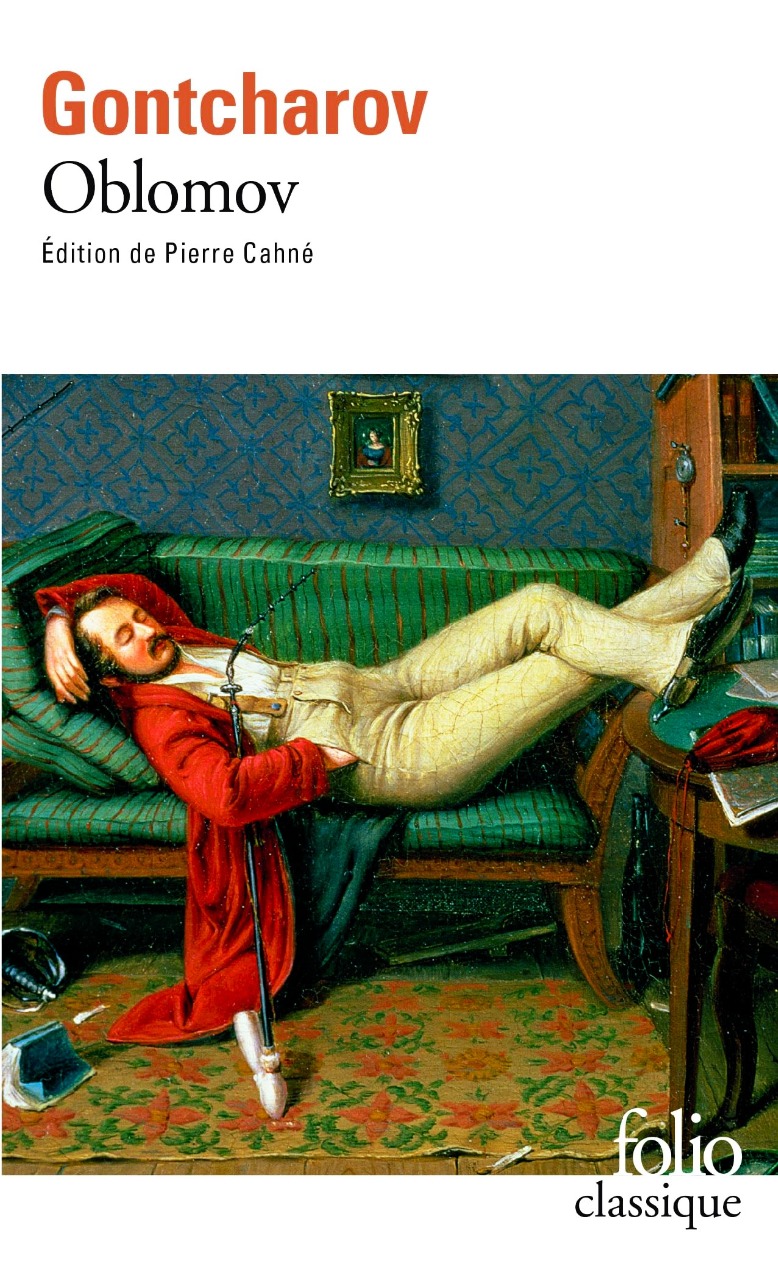

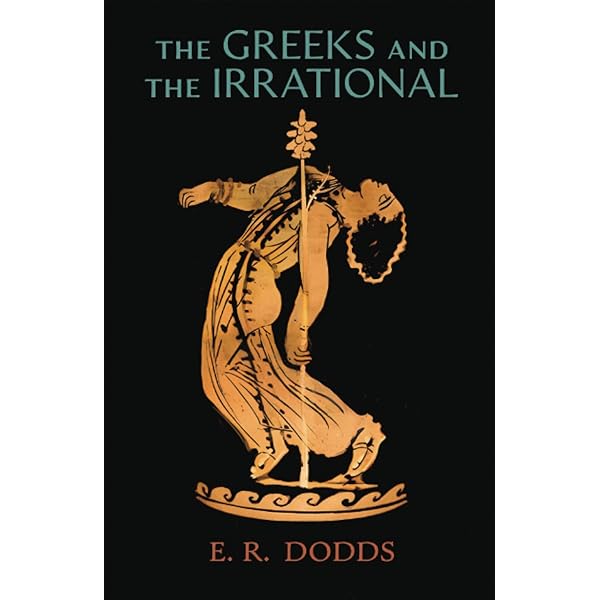

Fascinated, I continued to read other books by Harari – Sapiens and Nexus. But a certain oversaturation and scepticism soon made itself felt. Harari writes with a fleeting and captivating flair, but even if humanism and consideration spice up his descriptions, in my opinion, science takes over and people disappear from view. I find the same weakness in Max Tegmark – the large, sweeping perspectives dominate, but the “small world”, the one that I assume I have encountered among my students, among poor people in different parts of the world, with my friends and family, is somehow lost within the broad brushstrokes that create a big all-embracing picture, at the same time too vast and too simple.

It may be a misinterpretation, but I feel that both Tegmark and Harari move within a privileged bubble of like-minded individuals. Both of them were brilliant and talented students, early on noticed by generous like-minded mentors. And nothing bad about that. I assume it's absolutely excellent that they spread their knowledge in an accessible manner.

Both of them have founded foundations to spread their insights and are constantly seeking funding for various projects. And who doesn't? However, there is always a danger of conflicts of interest and a desire to simplify life to a far greater extent than it is.

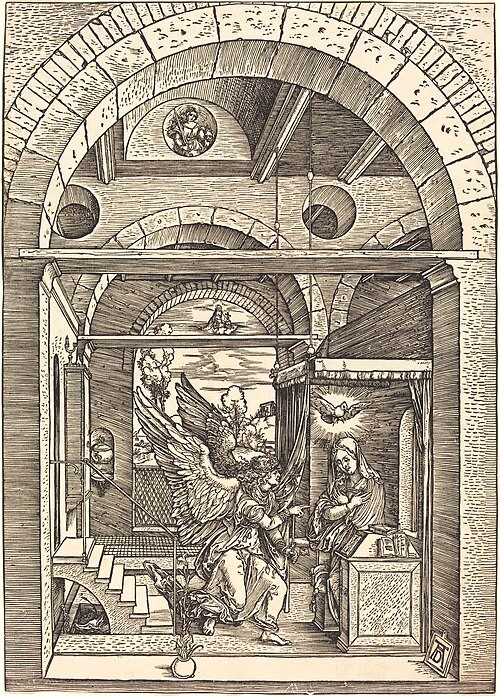

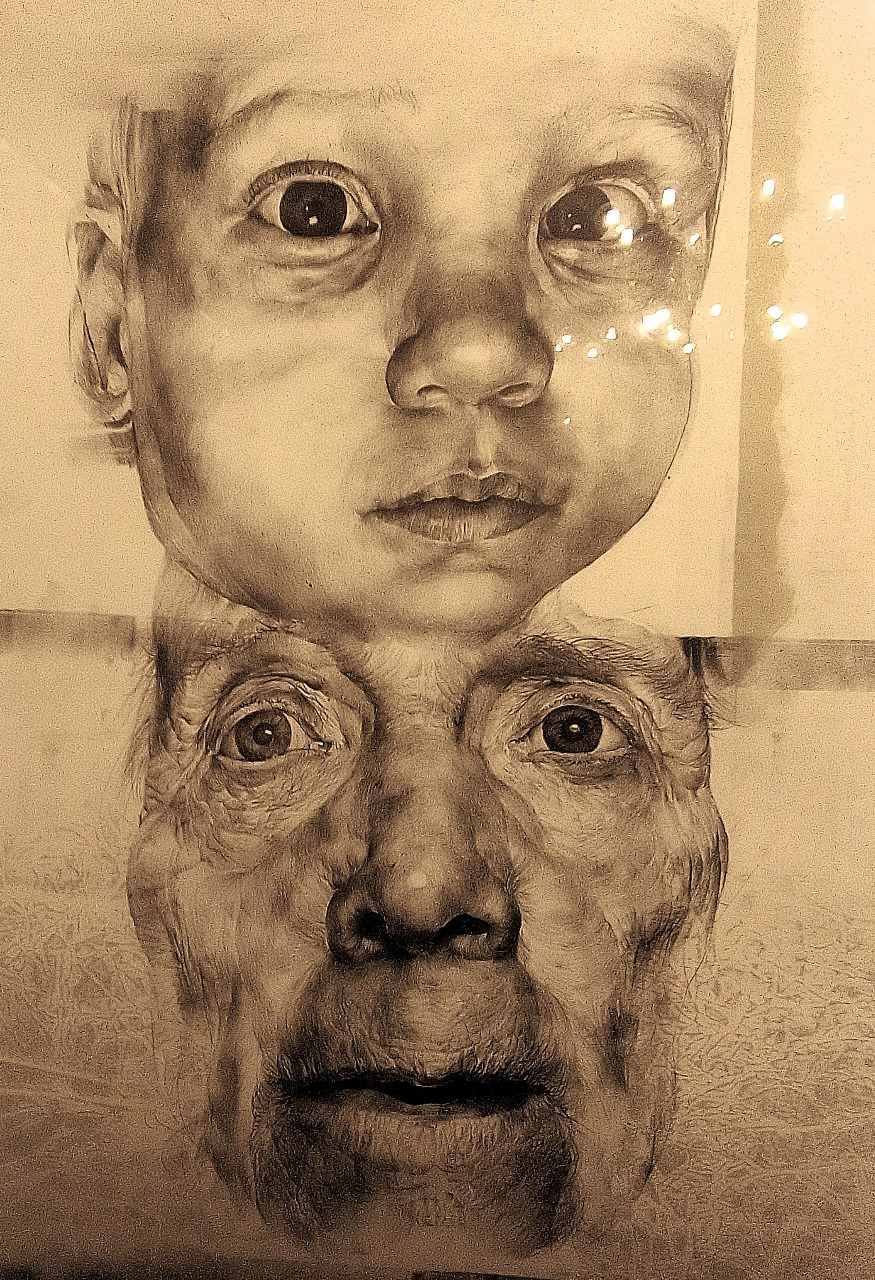

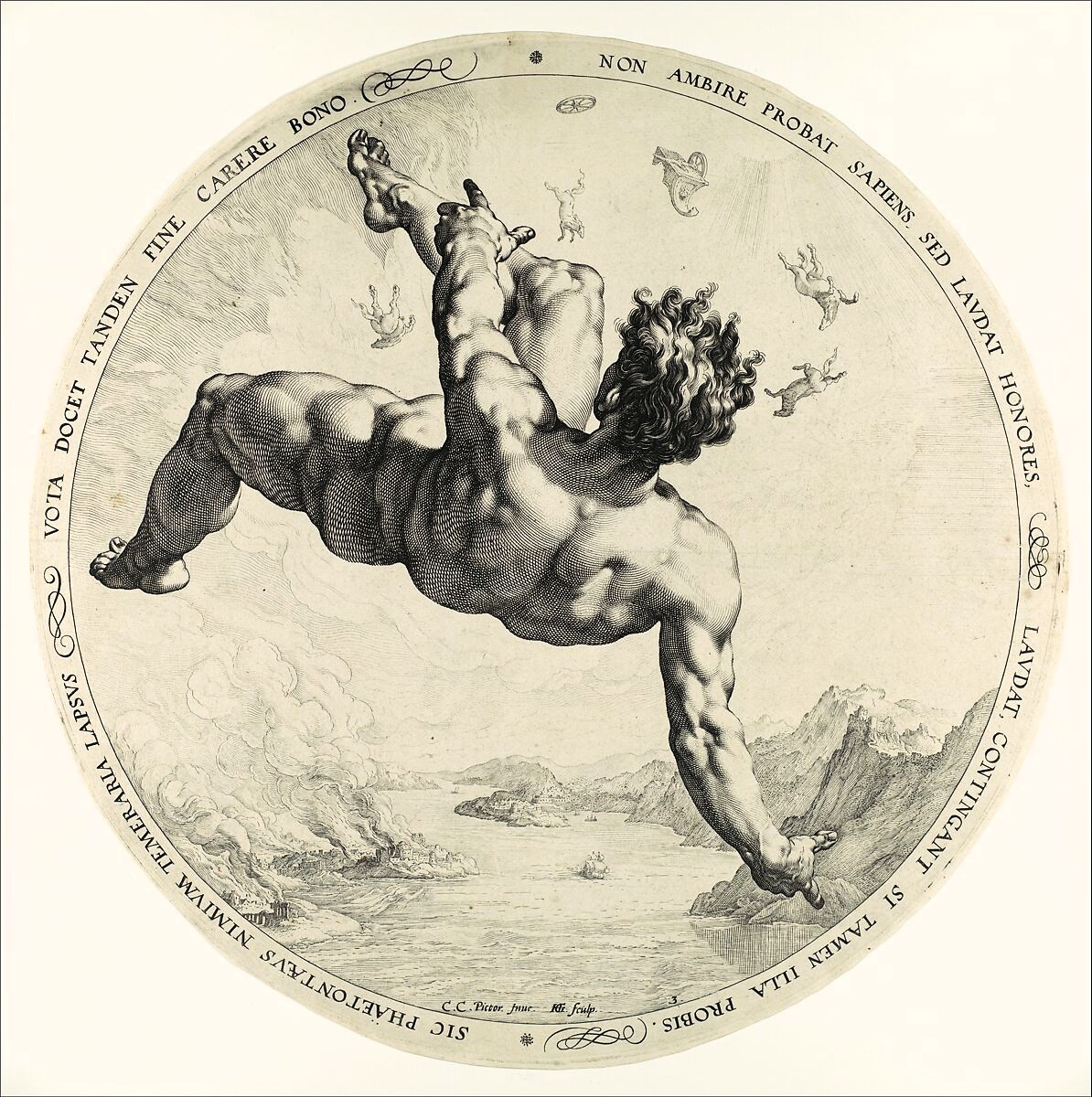

.jpg)

It is interesting that their books came out in the mid-2010s. A time that gave wind in the sails for A.I., which, according to many observers, has been more or less laying fallow for several years due to a lack of public interest and limited funding. However, Neural processing Units, NPUs, had begun to be used to accelerate neural networks, and an increasingly sophisticated deep learning quickly surpassed previous A.I. technologies. A growth that after 2017 was accelerated further through the so-called transformer architecture.

It can now be concluded that we are in the midst of an ever-increasing A.I. boom, which has already to some extent made Tegmark’s and Harari’s books obsolete and I am convinced that they and their colleagues are struggling hard to keep up with a development that has long since passed by an amateur like me.

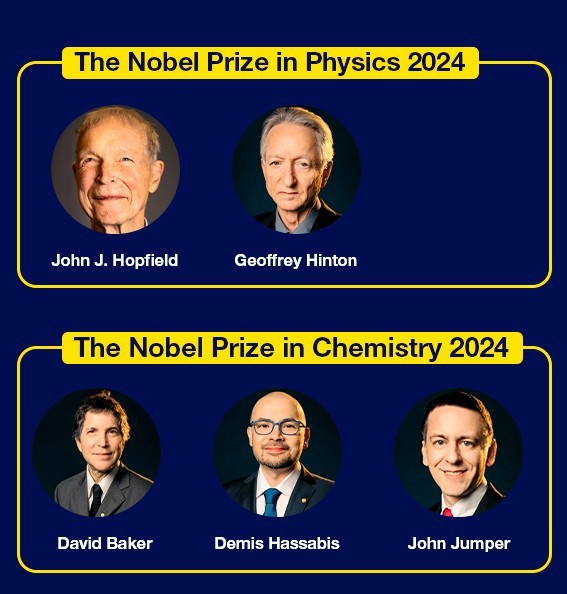

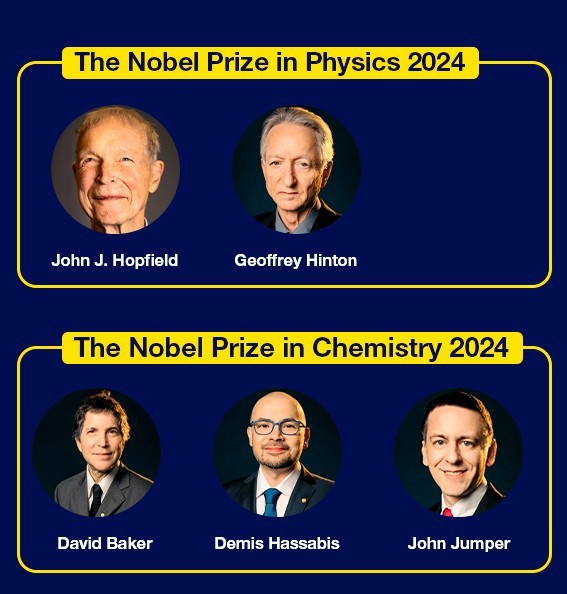

I realized this when I listened to a program dealing with 2024’s Nobel Laureates. That year’s physics laureates, Geoffrey Hinton and John Hopfield, are pioneers within A.I. research and received their award for:

Fundamental discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning by using artificial neural networks.

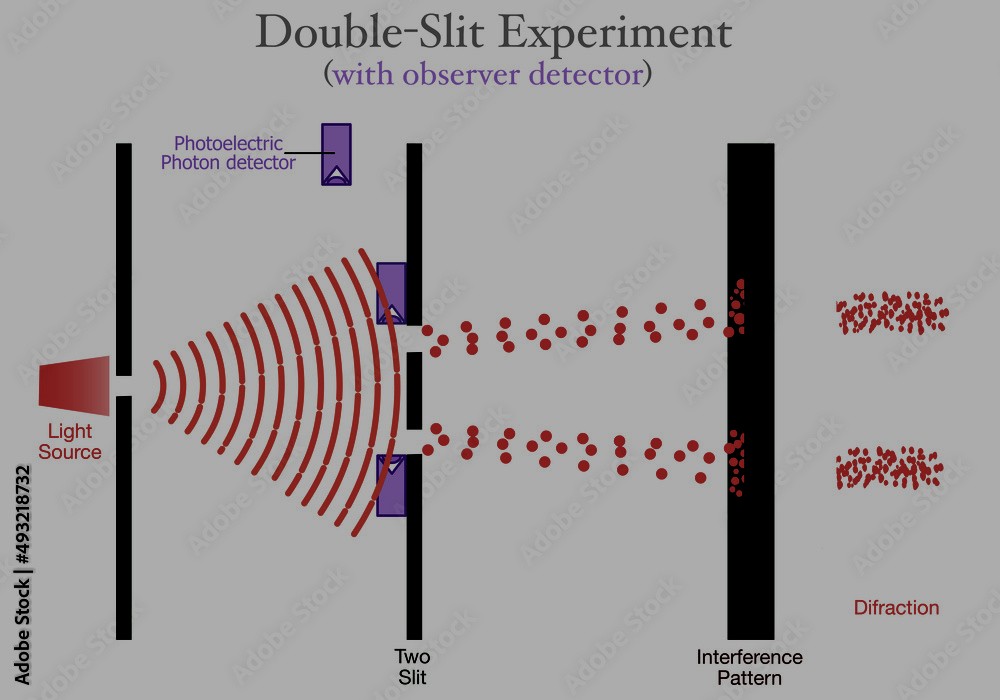

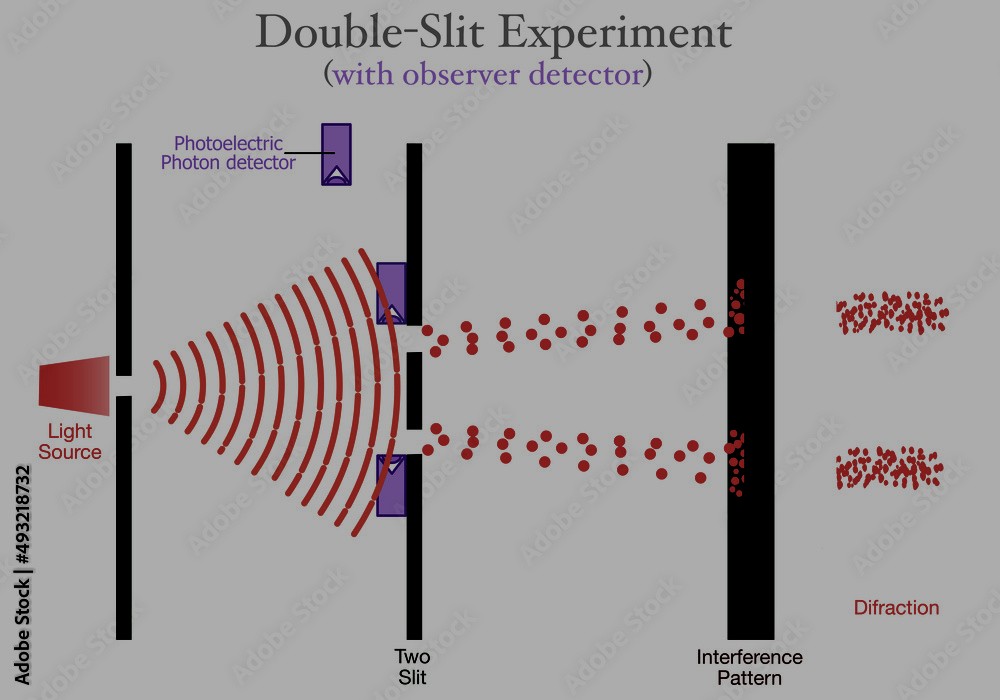

They use computers to investigate processes in the brain that include neuronal circuits/networks and study them both in their natural states, as well as through "synthetic" constructions in computer facilities. Brain activity varies between two phases, one where activity rapidly decreases and dies and another where activity builds up and intensifies over time. If you take this into account and assiduously examine the processes, both the brain's and computers' capacity for information processing might be increase.

Researchers now talk about “deep A.I.” referring to research inspired by biological neuroscience that among other processes involve “stacking” artificial neurons in layer upon layersand “train” them to process data.

This is all very puzzling to me, but what worried me while I listened to the radio programme was that both Hinton and Hopfield were calling for urgent research into A.I. safety to find ways to effectively control the A.I. systems, which are rapidly becoming smarter than humans.

A year before he received the Nobel Prize, Geoffrey Hinton had announced his resignation from a program called Google Brain in order to be able to speak out freely about the great risks associated with an overly rapid and thoughtless A.I. development. Both Hinton and Hopfield take every opportunity to express their concerns about the deliberate misuse of malicious actors, technological unemployment, and the existential risks posed by artificial general intelligence.

Chemistry Laureates David Baker, Demis Hassabis and John Jumper also conduct research on and with the help of A.I. and like Hopfield and Hinton, they also point out the major breakthrough that A.I. research had in the mid-2010s, as well as the dangers and benefits inherent in all A.I. research.

Hassabis, Baker and Jumper are researching the use of proteins as chemical tools. How proteins control and drive all the chemical reactions that together form the basis of life – proteins function as hormones, neurotransmitters, antibodies and building blocks within a wide variety of tissues.

Proteins are made up of 20 different amino acids, which can be described as the building blocks of life. In 2003, David Baker managed to use these blocks to design a new protein. Since then, his research group has created one protein after another, including proteins that can be used as drugs, vaccines, nanomaterials and small sensors.

As recently as 2020, Demis Hassabis and John Jumper presented an A.I. model that has been used to predict the structure of virtually all of the 200 million proteins that so far have been identified. Among a myriad of scientific applications that their model has made possible, researchers can now better understand antibiotic resistance and, for example, create enzymes capable of breaking down plastics.

The above is only a small selection of what will change everyone’s lives within an unimaginably short time. Hopefully for the better. Perhaps A.I. might give all of our children and grandchildren, as well as subsequent generations, a better world than the one that now is threatened by climate change, environmental destruction, war, injustice and intolerance.

Nevertheless, at the same time, it cannot be denied that lugubrious forces strive to exploit A.I. for their own narrow gain, for commercial interests, brain-destroying propaganda, refined warfare and mind control. And who can trust machines that program themselves?

Čapek, Karel(2004) R.U.R (Rossums Universal Robots). London: Penguin Classics. Dick, Philip K. (2007) Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? London: Gollancz. Ezra, Elizabeth (2019) Georges Méliès the birth of the auteur. Manchester: Manchester University Press.Gibson, William (1995) Neuromancer. New York: Harper Voyager. Harari, Yuval Noah (2017) Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow. New York: HarperCollins. Hoyle, Fred (2010) The Black Cloud. London: Penguin Modern Classics. Lem, Stanislaw (1991) Solaris. London: Faber & Faber. Printz-Påhlson, Göran (2011) Letters of Blood and Other Works in English. Cambrige: Open Book Publishers. Stapledon, Olaf (1999) Starmaker. London: Orion Publishing Group. Tegmark, Max (2017) Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence. London: Penguin Books.

Jag lever i en stad och är omgiven av hus och människor, men även en mängd prylar; böcker, skivor, filmer, TV och inte minst min dator. Detta är min lilla värld, min miljö, mitt habitat, och i allmänhet trivs jag här.

Jag kan även skifta miljö och har den fördelen att jag emellanåt kan vistas vid en tropisk strand, eller i en svensk skog. I det senare fallet kan jag under långa promenader, eller en roddtur på den närliggande sjön, låta mig uppslukas av naturens mäktiga närvaro; doften av grönska och jord, himlen ovanför mitt huvud, fåglarna och smådjuren.

Det är nu kallt i huset, mycket kallt. Det har stått obebott under en längre tid och efter skogspromenaden kurar jag ihop vid en den öppna spisen, i vilken jag lagt in rikligt med ved. Snart flammar elden stark och värmande och jag bryr mig inte längre om det kulna vädret utanför fönstret. Har på måfå tagit fram en bok ur hyllan – Allan Watts Nature, Man & Woman. Det var mycket länge sedan jag läste den, men redan efter ett par sidor väcker den flera tankar.

Watts skriver hur vi människor kan njuta och bedåras av naturen, vilken berikande känsla det är att ha fått denna gåva. Som i William Blakes underbara dikt, ständigt upprepad, men alltid lika fräsch och gripande:

To see a world in a grain of sand

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand,

And eternity in an hour.

Att se en värld i ett sandkorn

och en himmel i en vildblomma

Att ha oändligheten i din hand

och evigheten i en timme.

Men, som Watts så riktigt konstaterar – fisken som rör sig i det klara vattnet, fågeln som svävar över himlavalvet upplever inte världen och livet som ett mäktigt under:

Vi vet att fiskarna simmar i ständig rädsla för sina liv, för att inte märkas alltför mycket rusar de iväg; de är enbart nerver, skrämda till plötsliga piruetter vid minsta glimt av alarm. Vi vet att ”kärlek till naturen” är en sentimental förtrollning av yttre sken – att måsarna inte svävar över himlavalvet för sin njutnings skull, utan i vaksam hunger efter fisk, att de gyllene bina inte drömmer i liljorna utan besöker dem i en lika rutinmässig jakt efter honung som en hyresindrivare jagar efter skulder och att ekorrarna som fritt och glatt tycks leka mellan trädens grenar, är inte annat än frustrerade små pälsbollar av aptit och rädsla.

Men, likväl – vilken triumf att finnas till! Att vara människa och känna som Blake gjorde. Att stå hänförd inför tillvaron. Men, alltmer stängs vi in i en teknokratisk, A.I.-genererad värld. Är det en fördömelse, eller en välsignelse? Som det mesta här i livet – kanske både och. En sak är dock säker, och det är att vår värld, vårt habitat förändras med en oerhörd hastighet.

Under flera år har mina blogginlägg sällan attraherat fler än högst femtusen besökare per dag. Döm då om min förvåning då jag för någon månad sedan fann att de plötsligt stigit till mellan trettio- och fyrtiotusen besökare per dag. Vad hade hänt?

Med viss glädje, trots att jag säger mig att jag i själva verket skriver mina blogginlägg för mitt eget nöjes skull, blev jag glatt överraskad och inbillade mig att jag kanske hade nått vad en del skribenter kallar för en tipping point, nämligen att man efter trägen strävan plötsligt når en oväntad mängd läsare, något som inom bok- och nöjesbranschen kan ske helt oväntat. Begreppet var populärt för ett tiotal år sedan, men jag vet inte om man fortfarande talar så mycket om det.

Men, men, en vän konstaterade att den där plötsliga uppgången måste bero på A.I., Artificial Intelligence – det var säkerligen obemannade sökmotorer som skördade mina insikter för att mata in dem i det globala kunskapsnät som sedan slutet av 2022 glufsar i sig all upptänklig information, säkerligen även den som mina blygsamma blogginlägg kunde tänkas innehålla.

Det är främst ChatGPT som kommit att dominera den allmänna kunskapssfären. Det rör sig om en virtuell assistent som genom maskinlärning anammat en otrolig mängd information från böcker, websidor, diskussionsfora, filmer, serier, avhandlingar, tidningsartiklar, manualer och allt annat upptänkligt stoff som svävar kring därute i datormolnen. ChatGPT slukar nu all tillgänglig information (och antagligen mer än den) och serverar den till data-användare över hela världen.

Sedan några veckor tillbaka går det knappt att öppna vare sig sin dator eller smartphone utan att besväras påtvingade A.I.-tjänster. Tala om tipping point! På nolltid har världens datoranvändare mer eller mindre frivilligt blivit uppkopplade till en A.I.-skapad värld som för tillfället inte enbart slukar information utan även sväljer ofantliga mängder sötvatten. Vatten som vi behöver för att leva, använder för att dricka och för att hålla oss vid liv – åttio procent av vår kroppsvikt består av vatten. Vi kan inte leva längre än fem dagar utan dricksvatten och vi behöver vatten för att bevattna fält och grödor. Sötvatten utgör enbart tre procent världens vatten och det är de som vi behöver för att kunna leva och två tredjedelar av det ligger fortfarande otillgängligt i frusna glaciärer, som dock snabbt tinas upp och försvinner i odrickbart havsvatten.

De väldiga databaserade teknikföretagen, som Vidia, Microsoft, Google (Alphabet), Amazon och Meta, sätter nu i allt högre grad i sig vårt värdefulla och livsbevarande sötvatten för att kunna kyla och driva sina energislukande datacenter, där det behövs uppskattningsvis 9 liter sötvatten för varje använd kilowattimme.

Datateknikföretag är mer koncentrerade än andra energiintensiva anläggningar, såsom stålverk och kolgruvo. Dess byggnader konstrueras nära varandra så att de kan dela elnät och kylsystem och överföra information effektivt, både sinsemellan och till sina användare. I Irland står datacenter för mer än 20 procent av landets elförbrukning, de flesta av dem är belägna i utkanten av Dublin. I minst fem av USA:s delstater överstiger för närvarande sådana centers elförbrukning mer än 10 procent av staternas totala produktion.

Google bearbetar dagligen upp till 9 miljarder sökningar och varje sådan begäran via en A.I.-server kräver 7–9 wattimmars (Wh) energi, det vill säga en förbrukning av 63 till 81 liter vatten. Det är 23–30 gånger mer än den energi som krävs för en vanlig sökning. Den stora energiförbrukningen bidrar även till ökat koldioxidutsläpp. Det är dock möjligt att A.I.-utvecklingen är självreglerande och att energiförbrukningen därmed minskar, sådant har jag inte en aning om, det enda jag vet är att A.I.-tillväxten går med en rasande fart, något som jag och de flesta med mig, har upplevt på egen hand.

Från mitten av sjuttiotalet hade jag ingen egen dator utan använde universitets datorer, till vilka jag först begagnade hålkort, som snart ersattes av så kallade så kallade floppydiskar, men jag var fortfarande tvungen att lära mig vissa koder för att få det hela att fungera och vissa dagar stängdes hela nätet ner för att huvuddatorn blivit för varm.

Det var först senare, då jag med mitt forskningsstöd, köpte en McIntosh som jag kunde använda de mindre, hårda varianterna av floppydiskar. Jag var mycket glad för den där maskinen. Jag har kvar den och den fungerar fortfarande, men jag använder den givetvis aldrig. Jag har även kvar mina skrivmaskiner, en som jag fick av min fru strax efter det att vi träffats och en elektrisk variant som en av mina svågrar gett mig.

Något som jag nu uppskattar var att jag aldrig slösade min ungdom på de omfattande dataprogrammeringskurser som olika arbetsplatser försökte få mig att deltaga i. Min uppfattning var att ”snart kan du tala med din dator, så varför behöver jag då slösa värdefull tid på sådant som snart kommer att vara fullständigt förlegat”. Kanske kom sig min bestämda åsikt sig av att gjort min militärtjänstgöring som radiotelegrafist och efter min första repmånad funnit att det jag lärt mig av morsetelegrafering blivit lika aktuellt som kavallerichocker.

Min generation har alltså huvudlöst kastats in i en malström av oanad utveckling som många av oss har haft svårt att anpassa oss till. Jag känner det ibland som om jag lever kvar i medeltiden. Likt en gammal munk läser jag böcker och skriver lika ofta för hand som jag knappar på min dator. Utanför mitt rum brusar livet vidare och givetvis nås även jag av en del av dess kastvindar. För många, för egen del är jag inte riktigt säker, är den stadigt ökande hastigheten hos denna kringvirvlande orkan av halsbrytande, kommersiellt dominerad utveckling av artificiell intelligens milt sagt oroande.

På kort tid drabbar oss de mest förbluffande resultat av detta ”framåtskridande”. Speciellt om vi vistas inom den rikare och mer priviligierade sfären av vår omvärld. Kommer exempelvis mycket väl ihåg hur vi 1994 drabbades av Amazon, 1997 av Google, 2001 av Wikipedia (som jag faktiskt uppskattar), och 2004 av Facebook. Sedan följde en mängd sociala nätverkstjänster – Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, 4Chan, Linkedin, Pinterest, X, Reddit och jag vet inte hur många fler, förmodligen flera tusen. Grundarna av dessa och liknande webfenomen har för egen del har skapat sig makt och förmögenheter som övergår mänskligt förstånd.

Minns hur jag, efter några års frånvaro på sydligare breddgrader vid mitten av 1990-talet tog upp ett arbete på min gamla gymnasieskola och då fann att samtliga kollegor, i varje fall de flesta av dem, gick omkring med små sladdlösa telefoner. Sådant hade jag inte sett tidigare och något år senare fick jag av en vän hans gamla avlagda. Nya, effektivare modeller hade kommit ut och då liksom nu gällde det att vara tekniskt uppdaterad och innan de blivit hopplöst föråldrade införskaffa de senaste färskvarorna.

De flesta av oss har antagligen någonstans en låda med använda, numera tämligen värdelösa mobiltelefoner. Speciellt efter det att smartphones introducerats vid början av 2000-talet och numera har väl de flesta av dem personliga digitala assistenter, handflatstora datorer, bärbara mediaspelare, kompaktkameror, videokameror, spelkonsoler, e-läsare, fickräknare och GPS, samt mycket annat.

Sedan något år tillbaka har livet blivit komplicerat om du inte har en smartphone med installerad bank-kod och möjlighet att läsa QRkoder. Saknar du sådant ignoreras du av myndigheter, kan inte parkera din bil eller äta på restaurant. Koderna har successivt blivit till ett legitimationskort, en nyckel som öppnar och stänger portar och dessutom ännu en databaserad metod som gör att Storebror ser dig och kan påverka ditt liv.

Då jag efter ytterligare några år i fjärran länder började arbeta i Stockholm fann jag att välklädda yuppies gick omkring på gatorna och talade med sig själva, något jag tidigare enbart sett mentalt störda uteliggare i New York göra. Jag upptäckte dock att det var sina smartphones de konverserade med och att de för den skull bar ytterst diskreta öronsnäckor.

Under min barndom läste jag ofta Expressens seriebilaga där bland andra Dick Tracy fanns att läsa. Jag förundrades av detektivens TV-armbandstelefon som gjorde att han bildmässigt sedan mitten av 1960-talet kunde kommunicera sig med sina kollegor. Inte kunde jag då ana att smartphones snart skulle bli en verklighet.

Mest förbluffad blev jag 1996 då min fru och jag under en doktorandmiddag hamnat bredvid en forskare som berättade att han förvandlat sin dator till ett virtuellt akvarium i vilket han skapat en gädda och dess habitat. Han hade sedan genom olika simulationer manipulerat sin gäddas omgivning och tillvaro – tillsatt eller tagit bort syre, ändrat vattentemperaturen och dess surhetsgrad, experimenterat med en del miljöfarliga gifter, ökat och minskat ljuset och utfört en mängd olika virtuella experiment och vid flera tillfällen såväl dödat som återupplivat gäddan. Vi fann det hela intressant och tämligen märkligt. Inte undra på att vi undrade hur forskarens ”datorakvarium” såg ut, detta var ju långt innan A.I.:s framställningskonst blivit så sofistikerad som den är nu.